Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Characters and Events of Roman History, From Caesar to Nero, by Guglielmo Ferrero (published 1909).

In history as it is generally written, there are to be seen only great personages and events, kings, emperors, generals, ministers, wars, revolutions, treaties. When one closes a huge volume of history, one knows why this state made a great war upon that; understands the political thinking, the strategic plans, the diplomatic agreements of the powerful, but would hardly be able to answer much more simple questions: how people ate and drank, how warriors, politicians, diplomats, were clad, and in general how men lived at any particular time.

History does not usually busy itself with little men and small facts, and is therefore often obscure, unprecise, vague, tiresome. I believe that if some day I deserve praise, it will be because I have tried to show that everything has value and importance; that all phenomena interweave, act and react upon each other—economic changes and political revolutions, costumes, ideas, the family and the state, land-holding and cultivation. There are no insignificant events in history; for the great events, like revolutions and wars, are inevitably and indissolubly accompanied by an infinite number of slight changes, appearing in every part of a nation: if in life there are men without note, if these make up the great majority of nations—that which is called the “mass”—there is no greater mistake than to believe they are extraneous to history, mere inert instruments in the hands of the oligarchies that govern. States and institutions rest on this nameless mass, as a building rests upon its foundations.

I mean to show you now by a typical case the possible importance of these little facts, so neglected in history. I shall speak to you neither of proconsuls nor of emperors, neither of great conquests nor of famous laws, but of wine-dealers and vine-tenders, of the fortuned and famous plant that from wooded mountainslopes, mirrored in the Black Sea, began its slow, triumphal spread around the globe to its twentieth century bivouac, California. I shall show you how the branches and tendrils of the plant of Bacchus are entwined about the history and the destiny of Rome.

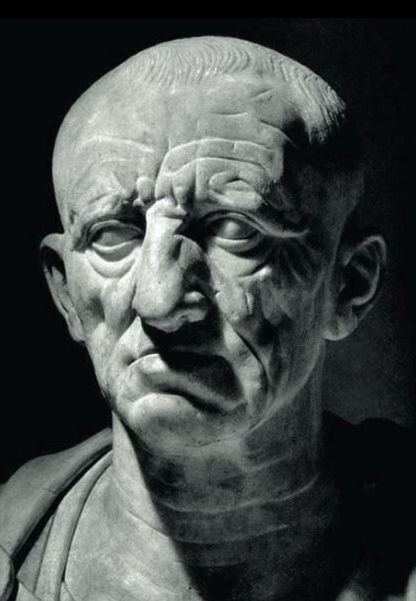

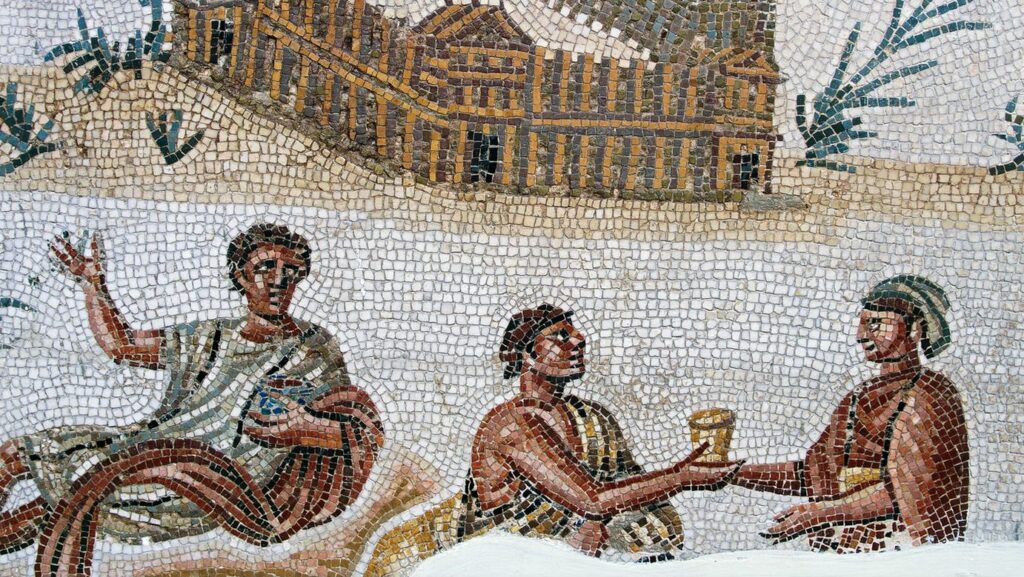

For many centuries the Romans were water-drinkers. Little wine was made in Italy, and that of inferior quality: commonly not even the rich were wont to drink it daily; many used it only as medicine during illness; women were never to take it. For a long time, any woman in Rome who used wine inspired a sense of repulsion, like that excited in Europe up to a short time ago by any woman who smoked. At the time of Polybius, that is, toward the middle of the second century B.C., ladies were allowed to drink only a little passum,—a kind of sweet wine, or syrup, made of raisins. About the women too much given to the beverage of Dionysos, there were terrifying stories told. It was said, for instance, that Egnatius Mecenius beat his wife to death, because she secretly drank wine; and that Romulus absolved him. (Pliny, Nat. Hist., bk. 14, ch. 13). It was told, on the word of Fabius Pictor, who mentioned it in his annals, that a Roman lady was condemned by the family tribunal to die of hunger, because she had stolen from her husband the keys of the wine-cellar. It was said the Greek judge Dionysius condemned to the loss of her dower a wife who, unknown to her husband, had drunk more than was good for her health: this story is one which shows that women began to be allowed the use of wine as a medicine. It was for a long time the vaunt of a true Roman to despise fine wines. For example, ancient historians tell of Cato that, when he returned in triumph from his proconsulship of Spain, he boasted of having drunk on the voyage the same wine as his rowers; which certainly was not, as we should say now, either Bordeaux or Champagne!

Cato, it is true, was a queer fellow, who pleased himself by throwing in the face of the young nobility’s incipient luxury a piece of almost brutal rudeness; but he exaggerated, not falsified, the ideas and sentiments of Romanism. At that time, it was a thing unworthy of a Roman to be a practised admirer of fine wines and to show too great a propensity for them. Then not only was the vine little and ill cultivated in Italy, but that country almost refused to admit its ability to make fine wines with its grapes. As wines of luxury, only the Greek were then accredited and esteemed—and paid for, like French wines to-day; but, though admiring and paying well for them, the Romans, still diffident and saving, made very spare use of them. Lucullus, the famous conqueror of the Pontus, told how in his father’s house—in the house, therefore, of a noble family—Greek wine was never served more than once, even at the most elegant dinners. Moreover, this must have been a common custom, because Pliny says, speaking of the beginning of the last century of the Republic, “Tanta vero vino græco gratia erat ut singulæ potiones in convitu darentur”; that is, translating literally, “Greek wine was so prized that only single portions of it were given at a meal.” You understand at once the significance of this phrase; Greek wine was served as to-day—at least on European tables—Champagne is served; it was too expensive to give in quantity.

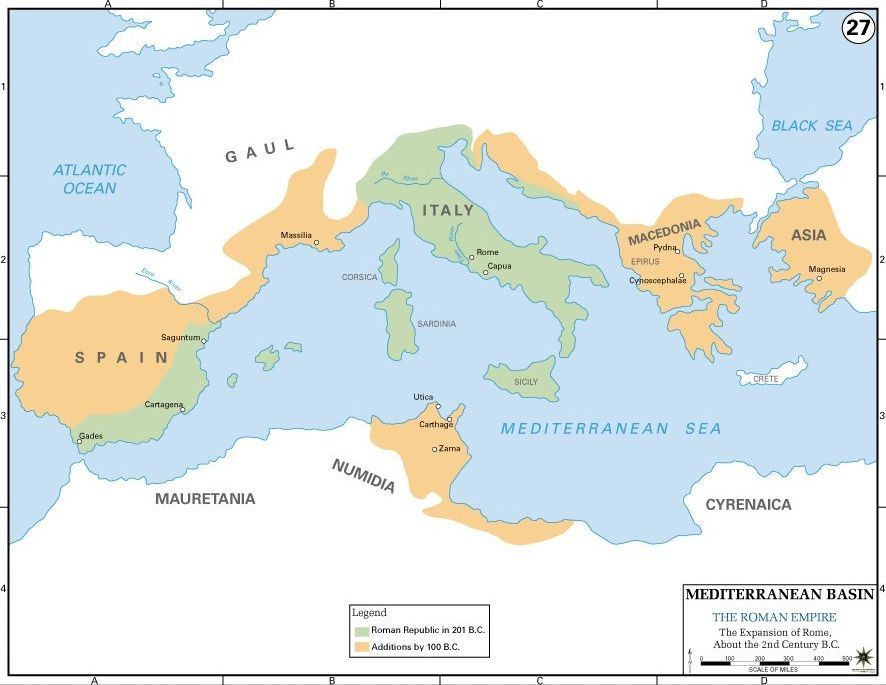

This condition of things began to change after Rome became a world power, went outside of Italy, interfered in the great affairs of the Mediterranean, and came into more immediate contact with Greece and the Orient. By a strange law of correlation, as the Roman Empire spread about the Mediterranean, the vineyard spread in Italy; gradually, as the world politics of Rome triumphed in Asia and Africa, the grape harvest grew more abundant in Italy, the consumption of wine increased, the quality was refined. The bond between the two phenomena—the progress of conquest and the progress of vine-growing—is not accidental, but organic, essential, intimate. As, little by little, the policy of expansion grew, wealth and culture increased in Rome; the spirit of tradition and simplicity weakened; luxury spread, and with it the appetite for sensations, including that of the taste for intoxicating beverages.

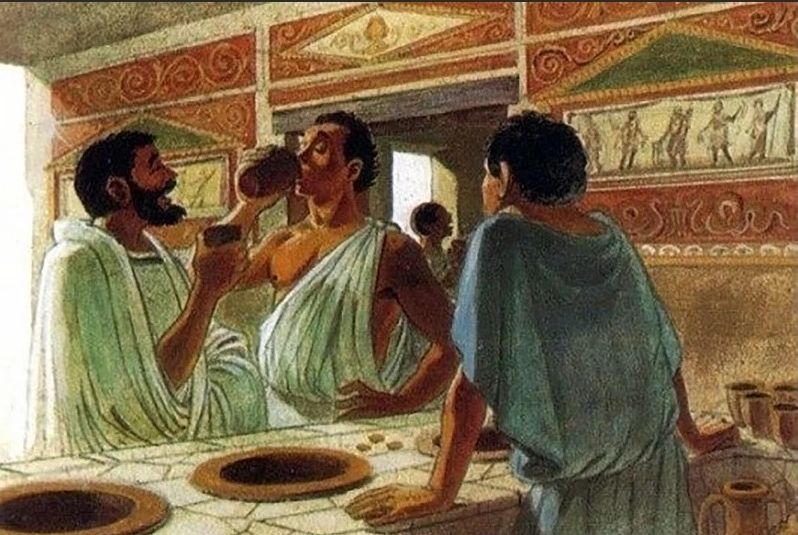

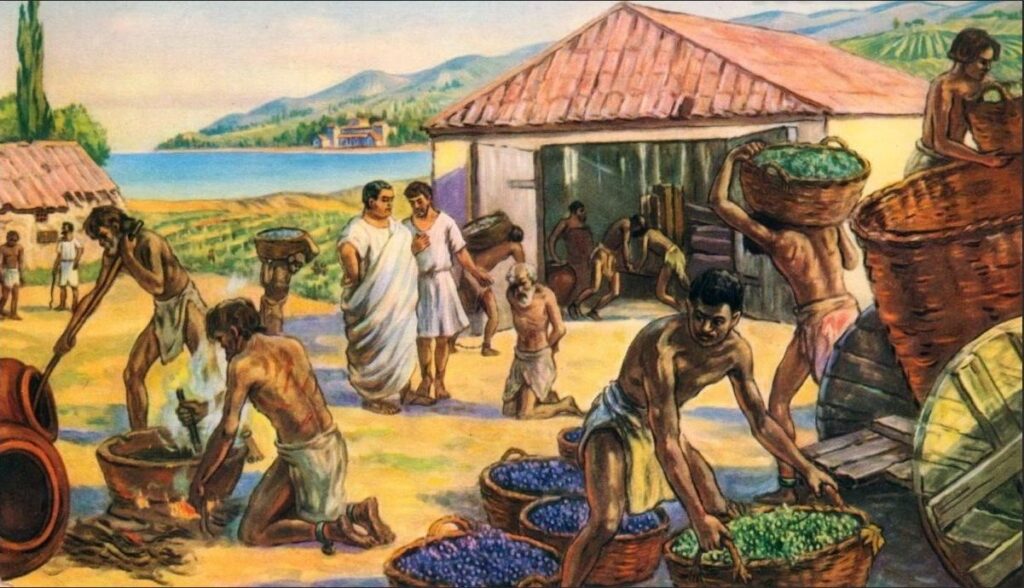

We have but to notice what happens about us in the modern world—when industry gains and wealth increases and cities grow, men drink more eagerly and riotously inebriating beverages—to understand what happened in Italy and in Rome, as gradually wars, tribute, blackmailing politics, pitiless usury, carried into the peninsula the spoils of the Mediterranean world, riches of the most numerous and varied forms. The old-time aversion to wine diminished; men and women, city dwellers and countrymen, learned to drink it. The cities, particularly Rome, no longer confined themselves to slaking their thirst at the fountains; as the demand and the price for wine increased, the land-owners in Italy grew interested in offering the cup of Bacchus, and as they had invested capital in vineyards, they were drawn on by the same interest to excite ever more eagerness for wine among the multitude, and to perfect grape-culture and increase the crop, in imitation of the Greeks. The wars and military expeditions to the Orient not only carried many Italians, peasants and proprietors, into the midst of the most celebrated vineyards of the world, but also transported into Italy slaves and numerous Greek and Asiatic peasants who knew the best methods of cultivating the vine, and of making wines like the Greek, just as the peasants of Piedmont, of the Veneto, and of Sicily, have in the last twenty years developed grape culture in Tunis and California.

Pliny, who is so rich in valuable information on the agricultural and social advances of Italy, tells us that it opened its hills and plains to the triumphal entrance of Dionysus between 130 and 120 B.C., about the time that Rome entered into possession of the kingdom of Pergamus, the largest and richest part of Asia Minor, left to it by bequest of Attalus. Thenceforward, for a century and a half, the progress of grape-growing continued without interruption; every generation poured forth new capital to enlarge the inheritance of vineyards already grown and to plant new ones. As the crop increased, the effort was redoubled to widen the sale, to entice a greater number of people to drink, to put the Italian wines by the side of the Greek.

At the distance of centuries, these vine-growing interests do not appear even in history; but they actually were a most important factor in the Roman policy, a force that helps us to explain several main facts in the history of Rome. For example, vineyards were one of the foundations of the imperial authority in Italy. That political form which was called with Augustus the principality, and from which was evolved the monarchy, would not have been founded if in the last century of the Republic all Italy had not been covered with vineyards and olive orchards. The affirmation, put just so, may seem strange and paradoxical, but the truth of it will be easy to prove.

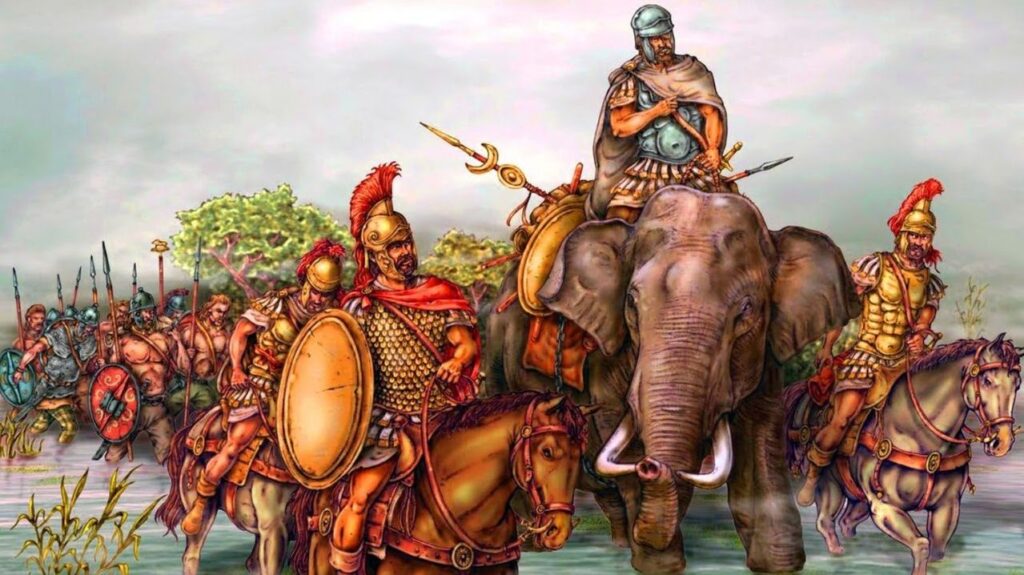

The imperial authority was gradually consolidated, because, beginning with Augustus, it succeeded in pacifying Italy after a century of commotion and civil wars and foreign invasions, to which the secular institutions of the Republic had not known how to oppose sufficient defense; so that, little by little, right or wrong, the authority of the Princeps, as supreme magistrate, and the power of the Julian-Claudian house, which the supreme magistrate had organised, seemed to the Italian multitude the stable foundation of peace and order. But why was Italy, beginning with the time of Cæsar, so desperately anxious for peace and order? It would be a mistake to see in this anxiety only the natural desire of a nation, worn by anarchy, for the conditions necessary to a common social existence. The contrast of two episodes will show you that during the age of Cæsar annoyance at disorder and intolerance of it had for a special reason increased in Italy. Toward the end of the third century B.C., Italy had borne on its soil for about seventeen years the presence of an army that went sacking and burning everywhere—the army of Hannibal—without losing composure, awaiting with patience the hour for torment to cease. A century and a half later, a Thracian slave, escaping from the chain-gang with some companions, overran the country,—and Italy was frightened, implored help, stretched out its arms to Rome more despairingly than it had ever done in all the years of Hannibal.

What made Italy so fearful? Because in the time of Hannibal it had chiefly cultivated cereals and pastured cattle, while in the days of Spartacus a considerable part of its fortune was invested in vineyards and olive groves. In pastoral and grain regions the invasion of an army does relatively little damage; for the cattle can be driven in advance of the invader, and if grain fields are burned, the harvest of a year is lost but the capital is not destroyed. If, instead, an army cuts and burns olive orchards and vineyards, which are many years in growing, it destroys an immense accumulated capital. Spartacus was not a new Hannibal, he was something much more dangerous; he was a new species of Phylloxera or of Mosca olearia in the form of brigand bands that destroyed vines and olives, the accumulated capital of centuries. Whence, the emperor became gradually a tutelary deity of the vine and the olive, the fortune of Italy. It was he who stopped the barbarians still restless and turbulent on the frontiers of Italy, hardly over the borders; it was he who kept peace within the country between social orders and political parties; it was he who looked after the maintenance and guarding of the great highways of the peninsula, periodically clearing them of robbers and the evil-disposed that infested them; and the land-owners, who held their vineyards and olive groves more at heart than they did the great republican traditions, placed the image of the Emperor among those of their Lares, and venerated him as they had earlier revered the Senate.

Still more curious is the influence that this development of Italian viticulture exercised on the political life of Rome; for example, in the barbarous provinces of Europe, wine was an instrument of Romanisation, the effectiveness of which has been too much disregarded. In Gaul, in Spain, in Helvetia, in the Danube provinces, Rome taught many things: law, war, construction of roads and cities, the Latin language and literature, the literature and art of Greece; more, it also taught to drink wine. Whoever has read the Commentaries of Cæsar will recall that, on several occasions, he describes certain more barbarous peoples of Gaul as prohibiting the importation of wine because they feared they would unnerve and corrupt themselves by habitual drunkenness. Strabo tells us of a great Gaeto-Thracian empire that a Gaetic warrior, Borebiste by name, founded in the time of Augustus beyond the Danube, opposite Roman possessions; while this chieftain sought to take from Greek and Latin civilisation many useful things, he severely prohibited the importation of wine. This fact and others similar, which might be cited, show that these primitive folk, exactly like the Romans of more ancient times, feared the beverage which so easily intoxicates, exactly as in China all wise people have always feared opium as a national scourge, and so many in France would today prohibit the manufacture of absinthe.

This hesitation and fear disappeared among the Gauls, after their country was annexed to the Empire; disappeared or was weakened among all the other peoples of the Danube and Rhine regions, and even in Germany, when they fell under Roman dominion; even also while they preserved independence, as little by little the Roman influence intensified in strength. By example, with the merchants, in literature, Rome poured out everywhere the ruddy and perfumed drink of Dionysos, and drove to the wilds and the villages, remote and poor, the national mead—the beverage of fermented barley akin to modern beer.

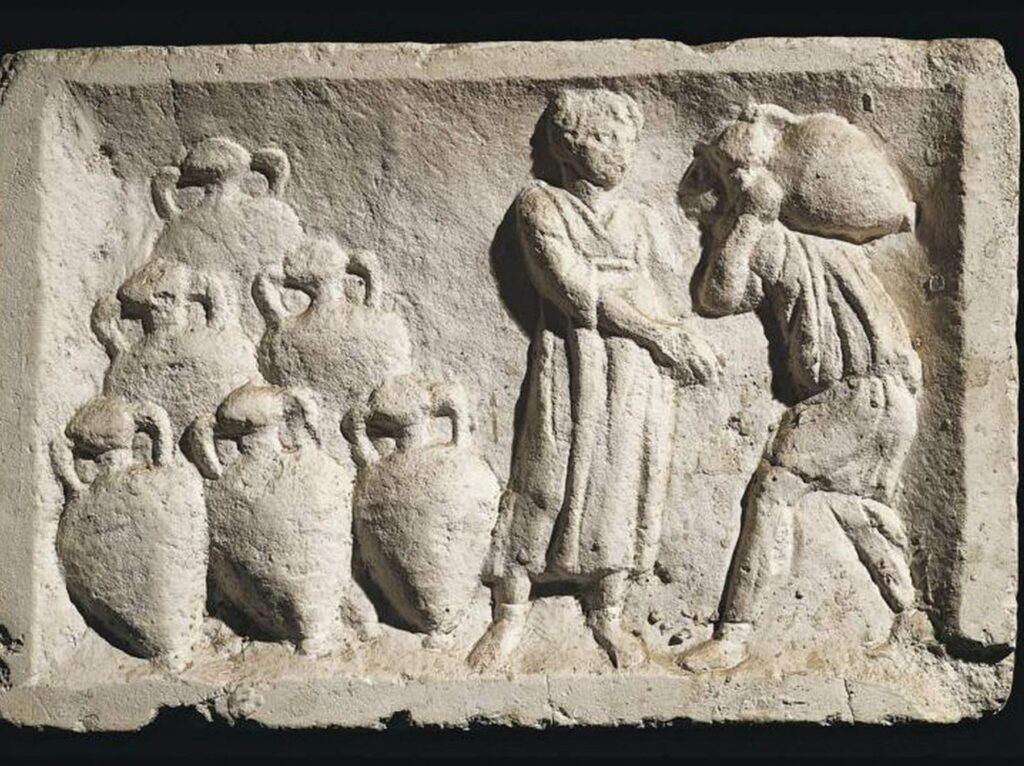

The Italian proprietors who were enlarging their vineyards—especially those of the valley of the Po, where already at the time of Strabo the grape-crop was very abundant—soon learned that beyond the Alps lived numerous customers. Under Augustus, Arles was already a large market for wines, both Greek and Italian; during the same period, there passed through Aquileia and Leibach considerable trade in Italian wine with the Danube regions. In the Roman castles along the Rhine, among the multitudes of Italians who followed the armies, there was not wanting the wine-dealer who sought with his liquor to infuse into the torpid blood of the barbarian a ray of southern warmth. Everywhere the Roman influence conquered national traditions; wine reigned on the tables of the rich as the lordly beverage, and the more the Gauls, the Pannonians, the Dalmatians, drank, the more money Italian proprietors made from their vineyards.

I have said that Rome diffused at once its wine and its literature: it also diffused its wine through its literature, a fact upon which I should like to dwell a moment, since it is odd and interesting for diverse reasons. We always make a mistake in judging the great literary works of the past. Two or three centuries after they were written, they serve only to bring a certain delight to the mind; consequently, we take for granted they were written only to bring us this delight. On the contrary, almost all literary works, even the greatest, had at first quite another office; they served to spread or counteract among the author’s contemporaries certain ideas and sentiments that the interests of certain directing forces favoured or opposed; indeed very often the authors were admired and remunerated far more for these services rendered to their contemporaries than for the lofty beauty of the literary works themselves.

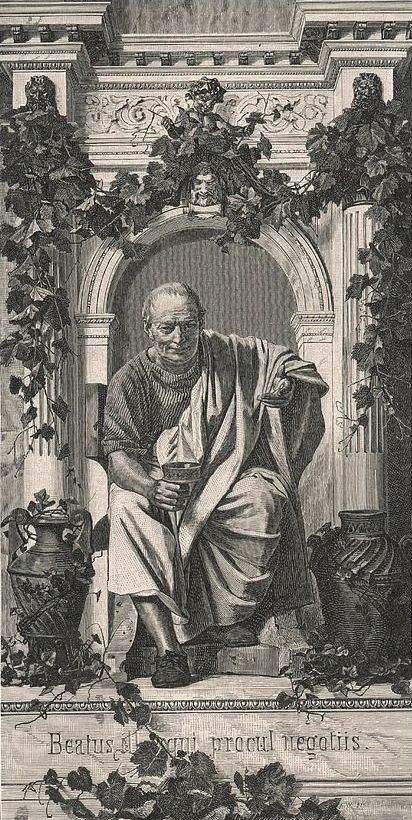

This is the case with the odes of Horace. To understand all that they meant to say to contemporaries, one must imagine Roman society as it was then, hardly out of a century of conquests and revolutions, in disorder, unbalanced, and still crude, notwithstanding the luxuries and refinements superficially imitated from the Orient; a society eager to enjoy, yet still ill educated to exercise upon itself that discipline of good taste, without which civilisation and its pleasures aggravate more than restrain the innate brutality of men. During the first period of peace, arrived after so great disturbance, that poetry so perfect in form, which analysed and described all the most exquisite delights of sense and soul, infused a new spirit of refinement into habits, and co-operated with laborious education in teaching even the stern conquerors of the world to enjoy all the pleasures of civilisation, alike literature and love, the luxury of the city and the restfulness of the villa, fraternal friendship and good cookery. It taught, too—this master poetry of the senses—to enjoy wine, to use the drink of Dionysos not the slake the thirst, but to colour, with an intoxication now soft, now strong, the most diverse emotions: the sadness of memories, the tenderness of friendship, the transports of love, the warmth of the quiet house, when without the furious storm and the bitter cold stiffen the universe of nature.

In the poetry of Horace, therefore, wine appeared as a proteiform god, which penetrates not only the tissues of the body but also the inmost recesses of the mind and aids it in its every contingency, sad or gay. Wine consoles in ill fortune (i., 7), suffuses the senses with universal oblivion, frees from anxiety and the weariness of care, fills the empty hours, and warms away the chill of winter (i., 9). But the wine that has the power to infuse gentle forgetfulness into the veins, has also the contrasting power of rousing lyric fervour in the spirit, the fervour heroic, divining, mystic (iii., 2). Finally, wine is also a source of power and heroism, as well as of joy and sensuous delight; a principle of civilisation and of progress (ii., 14).

I wish I could repeat to you all the Dionysic verse of this old poet from Venosa, whose subjects and motives, even though expressed in the choicest forms, may seem common and conventional in our time and to us, among whom for centuries the custom of drinking wine daily with meals has been a general habit. But these poems had a very different significance when they were written, in that society in which many did not dare drink wine commonly, considering it as a medicine, or as a beverage injurious to the health, or as a luxury dangerous to morals and the purse; in that time when entire nations, like Gaul, hesitated between the invitations of the ruddy vine-crowned Bacchus, come with his legions victorious, and the desperate supplications of Cervisia, the national mead, pale and fleeing to the forests. In those times and among those men, Horace with his dithyrambics affected not only the spirit but the will, uniting the subtle suggestion of his verses to all the other incentives and solicitations that on every side were persuading men to drink. He corroded the ancient Italian traditions, which opposed with such repugnance and so many fears the efforts of the vintners and the vineyard labourers to sell wine at a high price; in this way he rendered service to Italian viticulture.

The books of Horace, while he was still living, became what we might call school text-books; that is, they were read by young students, which must have increased their influence on the mind. Imagine that today a great European poet should describe and extol in magnificent verses the sensuous delight of smoking opium; should deify, in a mythology rich in imagery, the inebriating virtues of the product. Imagine that the verses of this poet were read in the schools: you may then by comparison picture to yourself the action of the poems of Horace.

The political and military triumph of Rome in the Mediterranean world signified therefore the world triumph of wine. So true is this, that in Europe and America today the sons of Rome drink wine as their national daily beverage. The Anglo-Saxons and Germans drink it in the same way as the Romans of the second century B.C., on formal occasions, or as a medicine. When you see at an European or American table the gold or ruby of the fair liquor gleaming in the glasses, remember that this is another inheritance from the Roman Empire and an ultimate effect of the victories of Rome; that probably we should drink different beverages if Cæsar had been overcome at Alesia or if Mithridates had been able decisively to reconquer Asia Minor from Rome. It astonishes you to see between politics and enology, between the great historical events and the lot of a humble plant, so close a bond.

I can show you another aspect of this phenomenon, even stranger and more philosophical. I have already said that at the beginning of the first century before Christ, although Italy had already planted many vineyards and gathered generous crops, Italian wines were still little sought after, while the contrary was true of the Greek. Pliny writes:

The wines of Italy were for long despised….Foreign wines had great vogue for some time even after the consulate of Opimius [121 B.C.], and up to the times of our grandfathers, although then Falernian was already discovered.

In the second half of the last century of the Republic and the first half of the first century B.C., this condition of things changed; Italian wines rose to great fame and demand, and took from the Greek the pre-eminence they so long had held. Finally, this pre-eminence formed one of the spoils of world conquest, and that not one of the meagrest. Pliny, writing in the second half of the first century, says (bk. 14, ch. 11):

Among the eighty most celebrated qualities of wine made in all the world, Italy makes about two thirds; therefore in this it outdoes other peoples.

The first wines that came into note seem to have been those of southern Italy, especially Falernian, and Julius Cæsar seems to have done much to make it known. Pliny tells us (bk. 14, ch. 15) that, in the great popular banquet offered to celebrate his triumph after his return from Egypt, he gave to every group of banqueters a cask of Chian and an amphora of Falernian, and that in his third consulate he distributed four kinds of wine to the populace, Lesbian, Chian, Falernian, and Mamertine; two Greek qualities and two Italian. It is evident that he wished officially to recognise national wines as equal to the foreign, in favor of Italian vintners; so that Julius Cæsar, that universal man, has a place not only in the history of the great Italian conquests, but also in that of Italian viticulture.

The wines of the valley of the Po were not long in making place for themselves after those of southern Italy. We know that Augustus drank only Rhetian wine; that is, of the Valtellina, one of the valleys famous also today for several delicious wines; we know that Livia drank Istrian wine.

I have said that Italy exported much wine to Gaul, to the Danube regions, and to Germany; to this may be added another remark, both curious and interesting. The Periplus of the Erytrian Sea, attributed to Arrianus, a kind of practice manual of geography, compiled in the second century A.D., tells us that in that century Italian wine was exported as far as India; so far had its fame spread! There is no doubt that the wealth in the first and second century A.D., which flowed for every section of Italy, came in part from the flourishing vineyards planted upon its hills and plains; and that the Italians, who had gone to the Orient for reasons political and financial, had fallen upon yet greater fortune in contrabanding Bacchus from the superb vineyards of the Ægean islands, and transporting him to the hills of Italy; a new seat whereon the capricious god of the vine rested for two centuries, until he took again to wandering, and crossed the Alps.

We may at this juncture ask ourselves if this enologic pre-eminence of Italy was the result only of a greater skill in cultivating the vine and pressing the grapes. I think not. It does not seem that Italy invented new methods of wine-making; it appears, instead, that it restricted itself to imitating what the Greeks had originated. On the other hand, it is certain, at least in northern and central Italy, that, although the vine grows, it does so less spontaneously and prosperously than in the Ægean islands, Greece, and Asia Minor, because the former regions are relatively too cold.

The great fame of Italian wines had another cause, a political: the world power and prestige of Rome. The psychological phenomenon is found in every age, among all peoples, and is one of the most important and essential in all history. What is beautiful and what is ugly? What is good and what is bad? What is true and what is false? In every period men must so distinguish between things, must adopt or repudiate certain ideas, practise or abandon certain habits, buy certain objects and refuse others; but one should not believe that all peoples make these discernments spontaneously, according to their natural inclination. It always happens that some nations succeed, by war, or money, or culture, in persuading the lesser peoples about them that they are superior; and strong in this admiration, they impose upon their susceptible neighbors, by a kind of continuous suggestion, their own ideas as the truest, their own customs as the noblest, their own arts as the most perfect.

For this reason chiefly, wars have often distant and complicated repercussions on the habits, the ideas, the commerce of nations. War, to which so many philosophers would attribute a divine spirit, so many others a diabolic, appears to the historian as above all a means—allow me the phrase, a bit frivolous, but graphic—of noisy réclame, advertisement for a people; because, although a more civilised people may be conquered by one more barbarous, less cultured, less moral; although also, the superiority in war may be relative, and men are not on earth merely to give each other blows, but to work, to study, to know, to enjoy; yet the majority of men are easily convinced that he who has won in a war is in everything, or at least in many things, superior to him who has lost. So it happened, for example, after the late Franco-Prussian War, that not only the armies organised or reorganised after 1870 imitated even the German uniform, as they has earlier copied the French, but in politics, science, industry, even in art, everything German was more generously admired. Even the consumption of beer heavily increased in the wine countries, and under the protection of the Treaty of Frankfurt, the god Gambrinus has made some audacious sallies into the territories sacred to Dionysos.

The same thing occurred in regard to wine in the ancient world. Athens and Alexander the Great had given to Greek wine the widest reputation, all the peoples of the Mediterranean world being persuaded that that was the best of all. Then the centre of power shifted to the west, toward the city built on the banks of the Tiber, and little by little as the power of Rome grew, the reputation of its wine increased, while that of Greece declined; until, finally, with world empire, Italy conquered pre-eminence in the wine market, and held it with Empire; for while Italy was lord, Italian wine seemed most excellent and was paid for accordingly.

This propensity of minor or subject peoples to imitate those dominant or more famous, is the greatest prize that rewards the pre-eminent for the fatigue necessary to conquer that place of honour; it is the reason why cultured and civilised nations ought naturally to seek to preserve a certain political, economic, and military supremacy, without which their intellectual superiority would weaken or at least lose a part of its value. The human multitude in the vast world are not yet so intelligent and refined as to prize that which is beautiful and grand for its own sake; and they are readily induced to admire as excellent what is but mediocre, if behind it there is a force to be feared or to impose it. Indeed, we may observe in the modern world a phenomenon analogous to that in historic Italy. What, in succeeding centuries, have been the changes in the enologic superiority conquered by Rome? Naturally I cannot recount the whole story, although it would be interesting; but will only observe that contemporary civilisation confirms the law by which predominance in the Latin world and the pre-eminence of wine are indissolubly bound together in history.

Paris is the modern Rome, the metropolis of the Latin world. France continues, as far as can be done in modern times, the ancient sway of Rome, irradiating round so much of the globe, by commerce, literature, art, science, industry, dominance of political ideas, the influence of the Latin world, making tributaries to Latin culture of barbarous peoples, and nations too young for leadership or grown too old; and France has inherited the pre-eminence in wines, although it lies at the farthest confines of the vine-bearing zone, beyond which the tree of Bacchus refuses to live. Do you realise that in all the wide belt of the earth where vineyards flourish, only the dry hills of Champagne ripen the delicious effervescent wine that refigures in modern civilisation—at least for those who are fond of wine—the nectar of the gods? And this, while effervescent wines are made in innumerable parts of the world and many are so good that one wonders if it were not possible for them, manufactured with care, placed in sightly bottles, and sold at as high a price as the most famous French Champagne, to dispute a part of the admiration that the devotees of Bacchus render to the French wine. Ah, they do not scintillate before the eyes of the world as symbols of gay intoxication like the others, for through those bottles passes no ray of the glory and prestige of France! An historian fond of paradoxes might affirm, and with great likelihood, what does not appear at first glance: that the great brands of French Champagne would not be sold so dear if the French Revolution had been suppressed by the European coalition, and if France, overcome in the terrible trial, had been enchained by the absolute monarchies of Europe like a dangerous beast. It would even be possible to declare that the reputation of Champagne is rooted, not only in the ground where the grapes are cultivated, and preserved in the vast cellars where the precious crops are stored, but in all the historic tradition of France, in all that which has given France worldly glory and power: the victorious wars, the distant conquests, the colonies, the literature, the art, the science, the money capital, and the spirit—cosmopolitan, expansive, dynamic—of its history. It would be possible to declare that it makes and pours into all the world its precious wine by that same virtue, intimate, national, and historic, by which it created the encyclopædia and made the Revolution, let Napoleon loose on Europe and founded the Empire, wrote so many famous books and built on the banks of the Seine the marvellous universal city, where all the forces of modern civilisation are gathered together and hold each other in equilibrium: aristocracy and democracy, the cosmopolite spirit and the spirit of nationality, money and science, war and fashion, art and religion. If France had not had its great history, Champagne would have remained an effervescing wine of modest household use that the peasants place every year in barrels for their own family consumption or to sell in the vicinity of the city of Rheims.

(1871-1942)