Editor’s Note: This is the fifth chapter of William the Conqueror, by Jacob Abbot (published 1877).

V. The Marriage

One of the most important points which an hereditary potentate has to attend to, in completing his political arrangements, is the question of his marriage. Until he has a family and an heir, men’s minds are unsettled in respect to the succession, and the various rival candidates and claimants to the throne are perpetually plotting and intriguing to put themselves into a position to spring at once into his place if sickness, or a battle, or any sudden accident should take him away. This evil was more formidable than usual in the case of William, for the men who were prepared to claim his place when he was dead were all secretly or openly maintaining that their right to it was superior to his while he was living. This gave a double intensity to the excitement with which the public was perpetually agitated in respect to the crown, and kept the minds of the ambitious and the aspiring, throughout William’s dominions, in a continual fever. It was obvious that a great part of the cause of this restless looking for change and consequent planning to promote it would be removed if William had a son.

It became, therefore, an important matter of state policy that the duke should be married. In fact, the barons and military chieftains who were friendly to him urged this measure upon him, on account of the great effect which they perceived it would have in settling the minds of the people of the country and consolidating his power. William accordingly began to look around for a wife. It appeared, however, in the end, that, though policy was the main consideration which first led him to contemplate marriage, love very probably exercised an important influence in determining his choice of the lady; at all events, the object of his choice was an object worthy of love. She was one of the most beautiful and accomplished princesses in Europe.

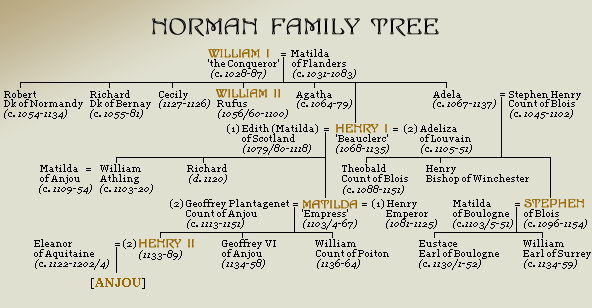

She was the daughter of a great potentate who ruled over the country of Flanders. Flanders lies upon the coast, east of Normandy, beyond the frontiers of France, and on the southern shore of the German Ocean. Her father’s title was the Earl of Flanders. He governed his dominions, however, like a sovereign, and was at the head of a very effective military power. His family, too, occupied a very high rank, and enjoyed great consideration among the other princes and potentates of Europe. It had intermarried with the royal family of England, so that Matilda, the daughter of the earl, whom William was disposed to make his bride, was found, by the genealogists, who took great interest in those days in tracing such connections, to have descended in a direct line from the great English king, Alfred himself.

This relationship, by making Matilda’s birth the more illustrious, operated strongly in favor of the match, as a great part of the motive which William had in view, in his intended marriage, was to aggrandize and strengthen his own position, by the connection which he was about to form. There was, however, another consanguinity in the case which had a contrary tendency. Matilda’s father had been connected with the Norman as well as with the English line, and Matilda and William were in some remote sense cousins. This circumstance led, in the sequel, as will presently be seen, to serious difficulty and trouble.

Matilda was seven years younger than William. She was brought up in her father’s court, and famed far and wide for her beauty and accomplishments. The accomplishments in which ladies of high rank sought to distinguish themselves in those days were two, music and embroidery. The embroidery of tapestry was the great attainment, and in this art the young Matilda acquired great skill. The tapestry which was made in the Middle Ages was used to hang against the walls of some of the more ornamented rooms in royal palaces and castles, to hide the naked surface of the stones of which the building was constructed. The cloths thus suspended were at first plain, afterward they began to be ornamented with embroidered borders or other decorations, and at length ladies learned to employ their own leisure hours, and beguile the tedium of the long confinement which many of them had to endure within their castles, in embroidering various devices and designs on the hangings intended for their own chambers, or to execute such work as presents for their friends. Matilda’s industry and skill in this kind of work were celebrated far and wide.

The accomplishments which ladies take great pains to acquire in their early years are sometimes, it is said, laid almost entirely aside after their marriage; not necessarily because they are then less desirous to please, but sometimes from the abundance of domestic duty, which allows them little time, and sometimes from the pressure of their burdens of care or sorrow, which leave them no heart for the occupations of amusement or gaiety. It seems not to have been so in Matilda’s case, however. She resumed her needle often during the years of her wedded life, and after William had accomplished his conquest of England, she worked upon a long linen web, with immense labor, a series of designs illustrating the various events and incidents of his campaign, and the work has been preserved to the present day.

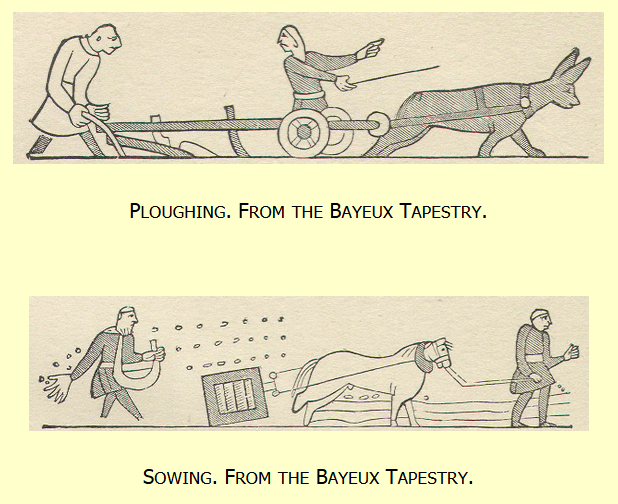

At least there is such a web now existing in the ancient town of Bayeux, in Normandy, which has been there from a period beyond the memory of men, and which tradition says was worked by Matilda. It would seem, however, that if she did it at all, she must have done it “as Solomon built the temple—with a great deal of help;” for this famous piece of embroidery, which has been celebrated among all the historians and scholars of the world for several hundred years by the name of the Bayeux Tapestry, is over four hundred feet long, and nearly two feet wide. The web is of linen, while the embroidery is of woolen. It was all obviously executed with the needle, and was worked with infinite labor and care. The woolen thread which was used was of various colors, suited to represent the different objects in the design, tough these colors are, of course, now much tarnished and faded.

The designs themselves are very simple and even rude, evincing very little knowledge of the principles of modern art. The specimens on the following page, of engravings made from them, will give some idea of the childish style of delineation which characterizes all Matilda’s designs. Childish, however, as such a style of drawing would be considered now, it seems to have been, in Matilda’s days, very much praised and admired.

We often have occasion to observe, in watching the course of human affairs, the frailty and transitoriness of things apparently most durable and strong. In the case of this embroidery, on the contrary, we are struck with the durability and permanence of what would seem to be most frail and fleeting. William’s conquest of England took place in 1066. This piece of tapestry, therefore, if Matilda really worked it, is about eight hundred years old. And when we consider how delicate, slender, and frail is the fiber of a linen thread, and that the various elements of decay, always busy in the work of corrupting and destroying the works of man, have proved themselves powerful enough to waste away and crumble into ruin the proudest structures which he has ever attempted to rear, we are amazed that these slender filaments have been able to resist their action so long. The Bayeux Tapestry has lasted nearly a thousand years. It will probably last for a thousand years to come. So that the vast and resistless power, which destroyed Babylon and Troy, and is making visible progress in the work of destroying the Pyramids, is foiled by the durability of a piece of needle-work, executed by the frail and delicate fingers of a woman.

We may have occasion to advert to the Bayeux Tapestry again, when we come to narrate the exploits which it was the particular object of this historical embroidery to illustrate and adorn. In the mean time, we return to our story.

The matrimonial negotiations of princes and princesses are always conducted in a formal and ceremonious manner, and through the intervention of legates, ambassadors, and commissioners without number, who are, of course, interested in protracting the proceedings, so as to prolong, as much as possible, their own diplomatic importance and power. Besides these accidental and temporary difficulties, it soon appeared that there were, in this case, some real and very formidable obstacles, which threatened for a time entirely to frustrate the scheme.

Among these difficulties there was one which was not usually, in such cases, considered of much importance, but which, in this instance, seemed for a long time to put an effectual bar to William’s wishes, and that was the aversion which the young princess herself felt for the match. She could have, one would suppose, no personal feeling of repugnance against William, for he was a tall and handsome cavalier, highly graceful and accomplished, and renowned for his bravery and success in war. He was, in every respect, such a personage as would be most likely to captivate the imagination of a maiden princess in those warlike times. Matilda, however, made objections to his birth. She could not consider him as the legitimate descendant and heir of the dukes of Normandy. It is true, he was then in possession of the throne, but he was regarded by a large portion of the most powerful chieftains in his realm as a usurper. He was liable, at any time, on some sudden change of fortune, to be expelled from his dominions. His position, in a word, though for the time being very exalted, was too precarious and unstable, and his personal claims to high social rank were too equivocal, to justify her trusting her destiny in his hands. In a word, Matilda’s answer to William’s proposals was an absolute refusal to become his wife.

These ostensible grounds, however, on which Matilda based her refusal, plausible as they were, were not the real and true ones. The secret motive was another attachment which she had formed. There had been sent to her father’s court in Flanders, from the English king, a young Saxon ambassador, whose name was Brihtric. Brihtric remained some little time at the court in Flanders, and Matilda, who saw him often at the various entertainments, celebrations, and parties of pleasure which were arranged for his amusement, conceived a strong attachment to him. He was of a very fair complexion, and his features were expressive and beautiful. He was a noble of high position in England, though, of course, his rank was inferior to that of Matilda. As it would have been deemed hardly proper for him, under the circumstances of the case, to have aspired to the princess’s hand, on account of the superiority of her social position, Matilda felt that it was her duty to make known her sentiments to him, and thus to open the way. She did so; but she found, unhappy maiden, that Brihtric did not feel, himself, the love which he had inspired in her, and all the efforts and arts to which she was impelled by the instinct of affection proved wholly unavailing to call it forth. Brihtric, after fulfilling the object of his mission, took leave of Matilda coldly, while her heart was almost breaking, and went away.

As the sweetest wine transforms itself into the sharpest vinegar, so the warmest and most ardent love turns, when it turns at all, to the most bitter and envenomed hate. Love gave place soon in Matilda’s heart to indignation, and indignation to a burning thirst for revenge. The intensity of the first excitement subsided; but Matilda never forgot and never forgave the disappointment and the indignity which she had endured. She had an opportunity long afterward to take terrible revenge on Brihtric in England, by subjecting him to cruelties and hardships there which brought him to his grave.

In the mean time, while her thoughts were so occupied with this attachment, she had, of course, no heart to listen favorably to William’s proposals. Her friends would have attached no importance to the real cause of her aversion to the match, but they felt the force of the objections which could justly be advanced against William’s rank, and his real right to his throne. Then the consanguinity of the parties was a great source of embarrassment and trouble. Persons as nearly related to each other as they were, were forbidden by the Roman Catholic rules to marry. There was such a thing as getting a dispensation from the pope, by which the marriage would be authorized. William accordingly sent ambassadors to Rome to negotiate this business. This, of course, opened a new field for difficulties and delays.

The papal authorities were accustomed, in such cases, to exact as the price, or, rather, as the condition of their dispensation, some grant or beneficial conveyance from the parties interested, to the Church, such as the foundation of an abbey or a monastery, the building of a chapel, or the endowment of a charity, by way, as it were, of making amends to the Church, by the benefit thus received, for whatever injury the cause of religion and morality might sustain by the relaxation of a divine law. Of course, this being the end in view, the tendency on the part of the authorities at Rome would be to protract the negotiations, so as to obtain from the suitor’s impatience better terms in the end. The ambassadors and commissioners, too, on William’s part, would have no strong motive for hastening the proceedings. Rome was an agreeable place of residence, and to live there as the ambassador of a royal duke of Normandy was to enjoy a high degree of consideration, and to be surrounded continually by scenes of magnificence and splendor. Then, again, William himself was not always at leisure to urge the business forward by giving it his own close attention; for, during the period while these negotiations were pending, he was occupied, from time to time, with foreign wars, or in the suppression of rebellions among his barons. Thus, from one cause and another, it seemed as if the business would never come to an end.

In fact, a less resolute and determined man than William would have given up in despair, for it was seven years, it is said, before the affair was brought to a conclusion. One story is told of the impetuous energy which William manifested in this suit, which seems almost incredible.

It was after the negotiations had been protracted for several years, and at a time when the difficulties were principally those arising from Matilda’s opposition, that the occurrence took place. It was at an interview which William had with Matilda in the streets of Bruges, one of her father’s cities. All that took place at the interview is not known, but in the end of it William’s resentment at Matilda’s treatment of him lost all bounds. He struck her or pushed her so violently as to throw her down upon the ground. It is said that he struck her repeatedly, and then, leaving her with her clothes all soiled and disheveled, rode off in a rage. Love quarrels are often the means of bringing the contending parties nearer together than they were before, but such a terrible love quarrel as this, we hope, is very rare.

Violent as it was, however, it was followed by a perfect reconciliation, and in the end all obstacles were removed, and William and Matilda were married. The event took place in 1052.

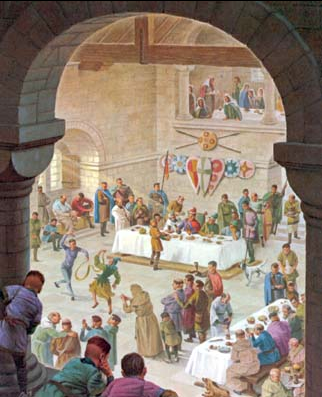

The marriage ceremony was performed at one of William’s castles, on the frontiers of Normandy, as it is customary for princes and kings to be married always in their own dominions. Matilda was conducted there with great pomp and parade by her parents, and was accompanied by a large train of attendants and friends. This company, mounted—both knights and ladies—on horses beautifully caparisoned, moved across the country like a little army on a march, or rather like a triumphal procession escorting a queen. Matilda was received at the castle with distinguished honor, and the marriage celebrations, and the entertainments accompanying it, were continued for several days. It was a scene of unusual festivity and rejoicing.

The dress both of William and Matilda, on this occasion, was very specially splendid. She wore a mantle studded with the most costly jewels; and, in addition to the other splendors of his dress, William too wore a mantle and a helmet, both of which were richly adorned with the same costly decorations. So much importance was attached, in those days, to this outward show, and so great was the public interest taken in it, that these dresses of William and Matilda, with all the jewelry that adorned them, were deposited afterward in the great church at Bayeux, where they remained a sort public spectacle, the property of the Church, for nearly five hundred years.

From the castle of Augi, where the marriage ceremonies were performed, William proceeded, after these first festivities and rejoicings were over, to the great city of Rouen, conducting his bride thither with great pomp and parade. Here the young couple established themselves, living in the enjoyment of every species of luxury and splendor which were attainable in those days. As has already been said, the interiors, even of royal castles and palaces, presented but few of the comforts and conveniences deemed essential to the happiness of a home in modern times. The European ladies of the present day delight in their suites of retired and well-furnished apartments, adorned with velvet carpets, and silken curtains, and luxuriant beds of down, with sofas and couches adapted to every fancy which the caprice of fatigue or restlessness may assume, and cabinets stored with treasures, and libraries of embellished books—the whole scene illuminated by the splendor of gas-lights, whose brilliancy is reflected by mirrors and candelabras, sparkling with a thousand hues. Matilda’s feudal palace presented no such scenes as these. The cold stone floors were covered with mats of rushes. The walls—if the naked masonry was hidden at all—were screened by hangings of coarse tapestry, ornamented with uncouth and hideous figures. The beds were miserable pallets, the windows were loop-holes, and the castle itself had all the architectural characteristics of a prison.

Still, there was a species of luxury and splendor even then. Matilda had splendid horses to ride, all magnificently caparisoned. She had dresses adorned most lavishly with gold and jewels. There were troops of valiant knights, all glittering in armor of steel, to escort her on her journeys, and accompany and wait upon her on her excursions of pleasure; and there were grand banquets and carousals, from time to time, in the long castle hall, with tournaments, and races, and games, and other military shows, conducted with great parade and pageantry. Matilda thus commenced her married life in luxury and splendor.

In luxury and splendor, but not in peace. William had an uncle, whose name was Mauger. He was the Archbishop of Rouen, and was a dignitary of great influence and power. Now it was, of course, the interest of William’s relatives that he should not be married, as every increase of probability that his crown would descend to direct heirs diminished their future chances of the succession, and of course undermined their present importance. Mauger had been very much opposed to this match, and had exerted himself in every way, while the negotiations were pending, to impede and delay them. The point which he most strenuously urged was the consanguinity of the parties, a point to which it was incumbent on him, as he maintained — being the head of the Church in Normandy — particularly to attend. It seems that, notwithstanding William’s negotiations with the pope to obtain a dispensation, the affair was not fully settled at Rome before the marriage; and very soon after the celebration of the nuptials, Mauger fulminated an edict of excommunication against both William and Matilda, for intermarrying within the degrees of relationship which the canons of the Church proscribed.

An excommunication, in the Middle Ages, was a terrible calamity. The person thus condemned was made, so far as such a sentence could effect it, an outcast from man, and a wretch accursed of Heaven. The most terrible denunciations were uttered against him, and in the case of a prince, like that of William, his subjects were all absolved from their allegiance, and forbidden to succor or defend him. A powerful potentate like William could maintain himself for a time against the influence and effects of such a course, but it was pretty sure to work more and more strongly against him through the superstitions of the people, and to wear him out in the end.

William resolved to appeal at once to the pope, and to effect, by some means or other, the object of securing his dispensation. There was a certain monk, then obscure and unknown, but who afterward became a very celebrated public character, named Lanfranc, whom, for some reason or other, William supposed to possess the necessary qualifications for this mission. He accordingly gave him his instructions and sent him away. Lanfranc proceeded to Rome, and there he managed the negotiation with the pope so dexterously as soon to bring it to a conclusion.

The arrangement which he made was this. The pope was to grant the dispensation and confirm the marriage, thus removing the sentence of excommunication which the Archbishop Mauger had pronounced, on condition that William should build and endow a hospital for a hundred poor persons, and also erect two abbeys, one to be built by himself, for monks, and one by Matilda, for nuns. Lanfranc agreed to these conditions on the part of William and Matilda, and they, when they came to be informed of them, accepted and confirmed them with great joy. The ban of excommunication was removed; all Normandy acquiesced in the marriage, and William and Matilda proceeded to form the plans and to superintend the construction of the abbeys.

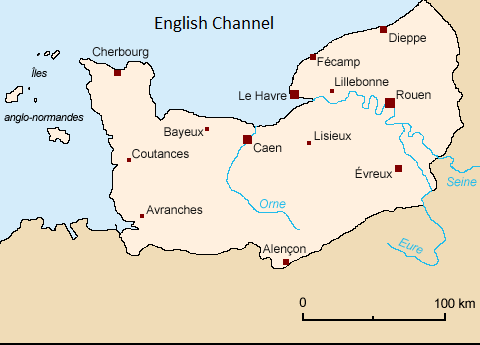

They selected the city of Caen for the site. The place of this city will be seen marked upon the map near the northern coast of Normandy. It was situated in a broad and pleasant valley, at the confluence of two rivers, and was surrounded by beautiful and fertile meadows. It was strongly fortified, being surrounded by walls and towers, which William’s ancestors, the dukes of Normandy, had built. William and Matilda took a strong interest in the plans and constructions connected with the building of the abbeys. William’s was a very extensive edifice, and contained within its inclosures a royal palace for himself, where, in subsequent years, himself and Matilda often resided.

The principal buildings of these abbeys still stand, though the walls and fortifications of Caen are gone. The buildings are used now for other purposes than those for which they were erected, but they retain the names originally given them, and are visited by great numbers of tourists, being regarded with great interest as singular memorials of the past—twin monuments commemorating an ancient marriage.

The marriage being thus finally confirmed and acquiesced in, William and Matilda enjoyed a long period of domestic peace. The oldest child was a son. He was born within a year of the marriage, and William named him Robert, that, as the reader will recollect, having been the name of William’s father. There was, in process of time, a large family of children. Their names were Robert, William Rufus, Henry, Cecilia, Agatha, Constance, Adela, Adelaide, and Gundred. Matilda devoted herself with great maternal fidelity to the care and education of these children, and many of them became subsequently historical personages of the highest distinction.

The object which, it will be recollected, was one of William’s main inducements for contracting this alliance, namely, the strengthening of his power by thus connecting himself with the reigning family of Flanders, was, in a great measure, accomplished. The two governments, leagued together by this natural tie, strengthened each other’s power, and often rendered each other essential assistance, though there was one occasion, subsequently, when William’s reliance on this aid was disappointed. It was as follows:

When he was planning his invasion of England, he sent to Matilda’s brother, Baldwin, who was then Count of Flanders, inviting him to raise a force and join him. Baldwin, who considered the enterprise as dangerous and Quixotic, sent back word to inquire what share of the English territory William would give him if he would go and help him conquer it. William thought that this attempt to make a bargain beforehand, for a division of spoil, evinced a very mercenary and distrustful spirit on the part of his brother-in-law—a spirit which he was not at all disposed to encourage. He accordingly took a sheet of parchment, and writing nothing within, he folded it in the form of a letter, and wrote upon the outside the following rhyme:

Beau frère, en Angleterre vous aures / Ce qui dedans escript, vous trouveres.

Which royal distich might be translated thus:

Your share, good brother, of the land we win, / You’ll find entitled and described within.

William forwarded the empty missive by the hand of a messenger, who delivered it to Baldwin as if it were a dispatch of great consequence. Baldwin received it eagerly, and opened it at once. He was surprised at finding nothing within; and after turning the parchment every way, in vain search after the description of his share, he asked the messenger what it meant “It means,” said he, “that as there is nothing writ within, so nothing you shall have.”

Notwithstanding this witticism, however, some arrangement seems afterward to have been made between the parties, for Flanders did, in fact, contribute an important share toward the force which William raised when preparing for the invasion.

[…] Source link […]