Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Famous Fighters of the Fleet, by Edward Fraser (published 1904).

The bombardment of Alexandria was brought about by the usurpation of power in Egypt by Arabi Pasha and the so-called National Party early in 1882, raising the cry of ‘Egypt for the Egyptians.’ Great Britain, alarmed at their avowed hostility towards her, was forced to intervene on behalf of her interests in Egypt, and to ensure the safety of the Suez Canal. Diplomacy, and all efforts to induce the Sultan, as suzerain of the Khedive, to take action, having failed, in June the British Mediterranean Fleet was ordered to the scene, at first by way of demonstration. A French squadron arrived at the same time, France being specially interested in Egypt under the Joint Control agreement, and other Great Powers sent representative ships. In reply Arabi and his partisans began throwing up works and mounting additional guns at Alexandria, and then riots broke out in the city and at Cairo leading to a massacre of Europeans. At the end of June the arming of the forts, which had been suspended under direct orders from Constantinople, was defiantly resumed, drawing strong remonstrances from the British Admiral, Sir Beauchamp Seymour, as the late Lord Alcester then was. The discovery of a plot to wreck part of the Suez Canal and to block Alexandria harbour, and the activity displayed on the fortifications, resulted in leave being telegraphed from England to the British Admiral to take action if necessary. Thereupon, on the 6th of July, Admiral Seymour demanded the immediate disarmament of the harbour forts on pain of bombardment. An evasive reply was given, while the mounting of heavy guns proceeded with increased vigour at night, as the searchlights of the fleet disclosed. On the 10th the British Admiral notified to the Governor of Alexandria that, unless in the course of that day certain of the harbour forts were evacuated and handed over to him to dismantle, he would open fire next morning. The foreign consuls were informed of Sir Beauchamp Seymour’s intention, and during the day all the foreign men-of-war withdrew outside, the French squadron proceeding to Port Said.

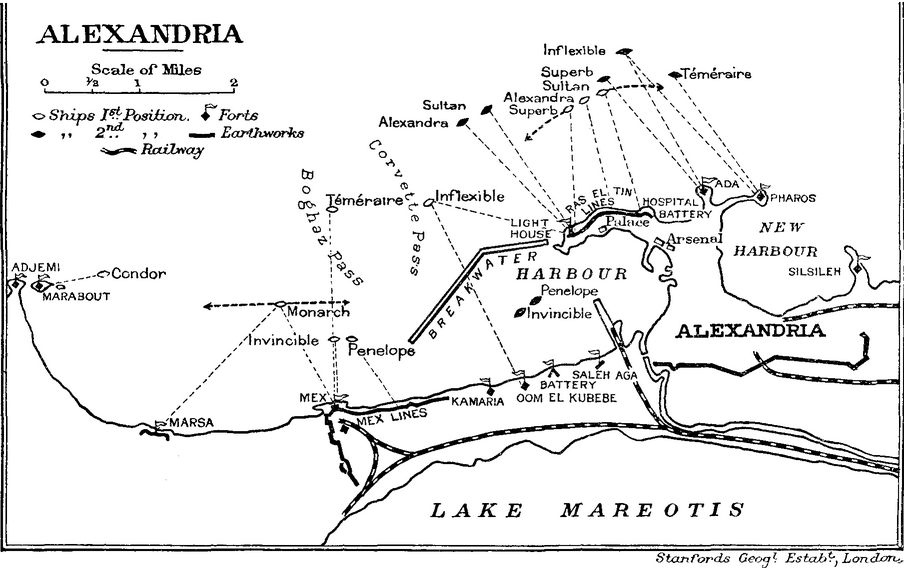

The British Fleet off Alexandria comprised eight battle-ships and five gun-vessels. When the British Admiral’s ultimatum was sent off on the morning of the 10th two of the battle-ships, the Invincible, on board which Admiral Seymour had his flag, and the Monarch, with the gun-vessel Condor commanded by Lord Charles Beresford, and the other gun-vessels, were inside the harbour. The rest of the fleet, the battle-ships Alexandra, Sultan, Inflexible, Téméraire, Superb, and Penelope, were lying outside.

At this point we take up the story of the Condor, and of the part she played in the events of the hour. As it happened, Mr. Frederic Villiers, the well-known artist and correspondent of the Graphic, was on board as the guest of Lord Charles Beresford. His vivid narrative of events gives a striking account of all that passed under his eyes.

For the last day or two everything had been ready and all the ships were kept cleared for action. The Egyptians were expected to throw off the mask and try to take the British fleet by surprise. Special precautions were taken on board the Condor, which lay well up the harbour in proximity to the Ras-el-Tin battery. There an exceptionally dangerous piece, a breech-loading gun firing a 250-lb. shot, and mounted on the Moncrieff disappearing system, was known to be in position. The Condor was a small second-class gun-boat of some 780 tons, and the thin iron sheeting on her sides was hardly stouter than a piece of cardboard. A rifle bullet could penetrate it, and there was not a scrap of armour about the ship. To protect his ship as far as possible against the big gun, Lord Charles, we are told, converted ‘the shore side of the Condor into a temporary ironclad by dressing her in chain armour. Every scrap of spare iron and chain on board was hung over her bulwarks, giving her a rakish list to starboard.’ Also, as Mr. Villiers relates, ‘all available canvas had been got out and draped round the inboard of the ship’s bulwarks. Hammocks had been slung round the wheel to protect the steersmen from splinters. The main[Pg 291]-topmast was lowered, the bowsprit run in and the Gatling in the main-top surrounded with canvas. Even the idlers, who constituted the engine-room artificers, stewards, and odd hands on board, were continually practised in drill.’

Shortly before sunset on the 10th Lord Charles Beresford, who had been for instructions on board the flagship, returned on board the Condor and turned up all hands. ‘He at once,’ says Mr. Villiers, ‘called the crew together and from the bridge addressed them to this effect.

‘”My men, the Admiral’s orders to the Condor are to keep out of action, to transfer signals, and to more or less nurse her bigger sisters, if they get into trouble.” Eloquent groans burst from the men. “But,” continued Beresford, “if an opportunity should occur,” and he (their commander) rather had an idea that it would, “the Condor was to take advantage of it and to prove her guns.” The crowd of upturned faces listening to these significant remarks now shone with satisfaction in the ruddy after-glow of the sunset, and then Lord Charles added: “No matter what happened, he was confident that they would give a good account of themselves and their smart little ship.” To see the gleam in their eyes, who could doubt that within them beat hearts as stout as in those hearts of oak of the grand old days?’

The Admiral’s instructions in writing, as issued to the commanders of the gun-vessels early next morning, ran thus. ‘They are,’ he said, ‘to take up a position as far out of the line of fire or of forts, or of the Inflexible, as convenient, moving away immediately it is found that fire is being directed on them. They will take advantage of every opportunity of annoying the enemy, especially where camps are to be seen, or where infantry or other troops are seen; but they are to avoid as much as possible the fire of the enemy’s heavy guns.’

‘There was little sleep that night,’ says Mr. Villiers. ‘As I lay in my cot … I could catch the familiar squeaking noise of the fiddle coming from the fo’c’sle, as the crew passed the feverish hours before the impending action with a horn-pipe or some popular ditty. Even the old gun-boat seemed to bestir herself long before dawn, for the hissing of steam and rattle of coal told me that the engineers were firing her for the eventful struggle with Arabi’s forts. At the first peep of day the Condor steamed off from her moorings, and followed the other vessels out of the harbour, as they took up their stations for bombarding.’

Even then, though, it seemed possible that there might be a slip ‘twixt cup and lip.

At daybreak on the 11th the despatch boat Helicon, which had been ordered to remain in harbour to the last, was seen standing out. She had signals flying that she had on board Egyptian officers with a letter from the Egyptian Government. The signal caused dismay for the moment among the men. They were already at quarters, braced up and eagerly awaiting the order to begin firing. Were the enemy going to back down at the last moment? But the suspense was not for long. The message, which purported to be a reply to the British Admiral’s ultimatum, was on the face of it merely a subterfuge to gain time. The bearers of it were sent back again with a written statement that their proposals were inadmissible. The Egyptian gunners in the batteries on shore, indeed, could be seen ready for action at their guns. As soon as the officers had been returned to shore the day’s work began.

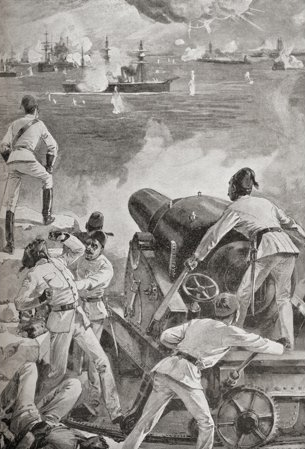

The opening scene may perhaps be best described in the words of the correspondent of the Standard newspaper, Mr. Cameron, afterwards killed in battle in the Soudan, who was on board the flagship Invincible. ‘At half-past six,’ he says, ‘a quiet order was passed round the decks, “Load with common shell.” A gleam of satisfaction shone on the men’s faces. Half-an-hour later a signal was made to the Alexandra to fire the challenging gun. That was done, and, the Egyptians continuing hostile preparations, the flags ran up at the Invincible’s mast-head for the fleet to commence action. The order was given on board the Invincible to begin “independent firing.” A deafening salvo from five 9-inch guns went from the side of the Invincible, while overhead the ten Nordenfelt guns in the tops swelled the din which burst forth from all the ships with a succession of drum-like tappings.

‘The smoke from the very commencement of the engagement was so dense that we could see nothing of the effect which our fire was producing, nor of what the enemy were doing; but soon after we began, a sharp scream overhead, followed by the uplifting columns of spray to seaward as the shots struck the water, made it clear that the enemy were replying to our iron salute…. They appeared to have got our range pretty accurately, and round and conical shot whistled thickly through the masts. I went round the ship and found the men fighting the main-deck guns all stripped to the waist. Between each shot they had to sit down and wait until the smoke cleared a little.’

Meanwhile the Condor and the other gun-vessels lay in the offing, behind the battle-ships that were engaging Fort Mex, looking on and awaiting their opportunity. The first thing that came the Condor’s way was to assist the Téméraire, which had got aground. The Téméraire was got off about eight o’clock, and immediately after that the Condor’s chance offered.

Lord Charles Beresford, as he watched the battle, had observed that the westernmost of the forts, Fort Marabout, was firing at the British inshore-squadron opposite Mex, the Invincible, Monarch, and Penelope, and apparently annoying them. He sent for one of his officers and said, ‘I shall stand down and make myself useful by engaging that fort.’ ‘You must be mad, sir,’ was the reply. ‘It is the second heaviest fort, and one shot from the heavy guns would knock us into smithereens.’ But the commander of the Condor was not to be put off that way. ‘The apparently impossible,’ he answered, ‘is often the easiest. Anyway, nothing can be done unless we try…. If I can get on the angle of the fort, I believe we can hit their guns without their hitting us. The thing is to get there.’

Fort Marabout mounted three 9-inch Armstrongs, firing 250-lb. shells; one 7-inch Armstrong, firing 115-lb. shells; eight 10-inch muzzle-loaders, firing 84-lb. hollow shot, or 100-lb. solid shot; seventeen 32-pounders, smooth-bores; and seven mortars, two firing 13-inch shells and five 11-inch mortars. There were also in this fort—whether mounted or not was unknown—two 10-inch Armstrongs, firing 400-lb. shells; two more 9-inch Armstrongs, and one 7-inch. Against that the little Condor set out to match herself, with one 7-inch gun, firing 12-lb. shells, and two 64-pounders, three 7-pounders, and one or two Gatlings. As has been said also, the little sloop had not an inch of armour on her sides or deck:—boilers, engines, magazines, all were open to the lightest of the enemy’s shot. All the same they steamed off towards the grey ramparts of the big fort without a moment of doubt or hesitation.

Mr. Villiers carries on the story.

‘The Condor steamed ahead. Our men stripped off their jackets. The decks were sanded, and the racers, or rails, on which the guns run were oiled.

‘As we neared Fort Marabout, its terraces and embrasures bristling with Armstrong guns, not a man aboard but knew the peril of our audacity,—for a little gun-boat, one of the smallest in Her Majesty’s service, to dare to attack the second most powerful fortress in Alexandria,—but the shout of enthusiasm from the crew when the order was given to “open fire!” readily showed their confidence in their beloved leader. The guns, run out “all a-port,” blazed away. The smoke hung heavily about the decks. The flash of the cannonade lit up for a moment the faces of the men, already begrimed with powder, and steaming with exertion, for the morning was hot and sultry. The captain from the bridge, glass in hand, watching anxiously the aim of her gunners, would shout from time to time: “What was that, my men?” ‘Sixteen hundred yards. Sir!” “Then give them eighteen this time, and drop it in.” “Aye, aye, Sir!”

‘Then a shout from the men on the main-mast told us on deck that the shot had made its mark. The little ship quaked again with the blast of her guns. The men were now almost black with powder, and continually dipped their heads in the sponge buckets to keep the grit from their eyes. One of our shots had fallen well within the enemy’s works; another had taken a yard of scarp off—for a slight breeze had lifted the fog of smoke, and all on board could plainly see the enemy working in their embrasures. The Arab gunners now trained one of their Armstrongs in our direction. Our engine-bell sounded, and the Condor at once steamed ahead. A puff of smoke from the fort, a dull boom, a rush of shell through the air, and a jet of water shot up far astern, followed by a shout from our men. The enemy had missed us. When the Arabs reloaded and brought to bear, the Condor steamed back again, and the shell whistled across her bows.

‘The enemy’s fire on the ships attacking Fort Mex slackened, and soon ceased altogether. Irritated by the constant fire of the little Condor, the Egyptian gunners now devoted their entire attention to us. They set about slewing their other Armstrongs in our direction. Their long black muzzles slowly turned their gaping mouths towards us. We looked at each other, then some of us looked at the captain, for the situation was becoming critical…. In an instant he decided,’ proceeds Mr. Villiers, ‘and gave the order for the Condor to run in closer, and we came within 1200 yards. We all saw in a moment the wisdom of the seeming audacity. We were well within their guard; though the Gyppies blazed at us, they could only practise at our masts; they could not depress their guns sufficiently to hull us. We cheered again and again as their abortive attempts to get at us failed, for a shot below water-mark, with the lurch the Condor was already making with all her guns abroadside, would have sent her down to Davy Jones’s locker in less than ten minutes.

‘The Egyptians, in their rage, opened fire with their smooth-bores from the lower parapet. The round-shot would whistle through our rigging, making us lie low awhile; but we would scramble to our feet again, dropping another 9-inch shell well within their works, scattering their gunners, and making things quite unpleasant for them. Only once did the enemy touch us, when a deep thud started the little ship trembling from stem to stern. The carpenter was ordered below. There was an anxious moment or two, when at last he returned, reporting the glad news that “all was well”; we had only been grazed.’

It may be noted, by the way, that at twelve hundred yards a gun like the 9-inch guns on Fort Marabout has a velocity of 1233 feet a second, and a penetrative power equal to carrying their 250-lb. shot clean through a target of wrought iron nine and a half inches thick. Had only one of these projectiles hit fairly, there would have been an end of the Condor, there and then. That is certain. At the same time, at twelve hundred yards the time of flight of a shot from muzzle to mark would be 2.72 seconds, and the shot in that period would drop 75½ feet. It was not an impossible task for the Egyptian gunners on the ramparts to hit the Condor. That they failed utterly was the Condor’s luck—the fortune of war, pure and simple. The Condor’s crew through it all seemed to bear charmed lives. Shots fell thick in the water all round, as other ships observed, or cut the rigging overhead. One big shot tore the awning over the quarter-deck. A 10-inch shell struck the water close underneath the ship’s bows, and the column of water sent up by the splash knocked an officer and two men off the forecastle.

To resume with Mr. Villiers.

‘It was a scorching, thirsty time on deck. The particles of carbon from the powder floating in the air dried our throats till we almost choked. The captain’s steward was always ready to quench the thirst of the guests, Mr. Moberly Bell, the now famous manager of the Times, and myself, with cool drinks whenever we found time between the shots to rush below; but just as the tumbler reached our lips the blast of the guns would almost shatter the glass against one’s teeth, and we would rush on deck to see how the shot had told.

‘All the time the navigating lieutenant, with eyes fixed on the chart, was calmly moving the vessel up and down a narrow tortuous passage which we could distinctly see, by peering over the side of the vessel, for the reefs on either flank of the narrow channel glistened from out the blue-black of the waters.’

Here is Lord Charles Beresford’s own account of the Condor’s day at Alexandria, as briefly given once to an interviewer. ‘The Téméraire got aground on the northern part of the Boghaz Pass, so we went down and towed her off. Whilst doing so the Marabout Fort opened fire on the English ships inside the bar. The idea struck me that the Condor being small, with low freeboard, might get through the zone of fire and under the fort. It wasn’t altogether easy work, for had one shell struck the Condor fair and square we should have been sunk to a dead certainty. However, she was easy to handle, and when once we were on the angle of the fort and under it we were all right. My dodge was to throw a couple of missiles into the fort at a time, and then back or fill, as the case might be, so that just when the Egyptians thought[Pg 302] they had got our right range, the Condor was out of the way, and so it went on pretty well all day. The men behaved splendidly,—upon my word, I don’t think they have their equals!’

For upwards of two hours the Condor fought Fort Marabout, and then the Admiral, apparently thinking that she had as much as she could manage, signalled to the Beacon, another gun-vessel (Commander G.W. Hand), and the senior officer’s ship of the flotilla, for the Bittern, Cygnet, and Decoy to go to her assistance. The fort, though, had already, by that, been practically subdued. The Egyptians had had enough, and soon afterwards ceased firing, although they kept their flag flying until next day, when the officer who is now Admiral Sir A.K. Wilson, V.C., landed, and hauled it down. He presented the colours of Marabout to Lord Charles Beresford, in whose possession they are now, together with another trophy of the fight, a fragment of one of the Condor’s shells which was found to have passed through the magazine of Fort Marabout, and did not explode until outside. Among his most treasured mementos Lord Charles also preserves the Condor’s binnacle, as taken from the ship when, some ten or twelve years later, she passed into the shipbreakers’ hands at Dead Man’s Bay, Plymouth Sound.

In her action with Fort Marabout the Condor expended over nineteen and a half hundredweights of powder (a ton all but fifty-four pounds), and two hundred and one projectiles:—65 rounds of 7-inch shell, 128 64-pounder shells, and eight 7-pounder shells; besides 200 rounds of Gatling gun ammunition, 13 war-rockets, and 1000 rounds of Martini-Henry small-arm ammunition.

When the gun-boats had finished their work Admiral Seymour made the signal of recall, and they returned, passing close to the Invincible to their stations.

Now it was that the celebrated signal to the Condor was made. The little vessel was passing the flagship, from on board which the Invincible’s men were cheering her enthusiastically, when the Admiral on the quarter-deck turned to his flag-lieutenant, Lieutenant Hedworth Lambton,—the future captain of the Powerful and the man who saved Ladysmith,—and said, as if musing to himself, ‘I should like to tell them something.’ Lieutenant Lambton made a suggestion, and within less than a minute, the flags went up at the Invincible’s mast-head making the words, ‘Well Done, Condor!’ That is the story of the Condor at Alexandria. The day ended for her with covering the landing-party sent ashore at the close of the bombardment to spike the guns of Fort Mex.

The story of the Condor alone, of all the ships at the bombardment of Alexandria, has been told. For one reason or another, what the little gun-boat did in the action appealed specially to people at the time, and attracted universal attention. It was, of course, largely a matter of opportunity—the seizing of an exceptional chance for an effort of individual daring. All at Alexandria did well, and the Condor had the best of the luck. In fairness, a few words must be also said of others of the ships present on the occasion, and of the part that they individually took in the fighting.

In addition to the Condor, another ship won the honour of a special signal ‘Well Done!’ from the Admiral—the big Inflexible, captained on that day by the officer who is now Admiral Sir John Arbuthnot Fisher, G.C.B., First Sea Lord of the Admiralty. The Inflexible during the earlier part of the engagement was posted outside the reefs off the ‘Corvette Pass’ entrance to Alexandria harbour, enfilading the Lighthouse batteries. ‘It is invidious to particularise,’ says the Times correspondent, who was on board another ship in the fleet, ‘but the Inflexible’s firing to-day was certainly second to none.’ Describing how the Inflexible shifted her position, and at ranges between 3000 and 5000 yards shelled the Mex Fort with one turret, and the Ras-el-Tin batteries with the other, the correspondent continues: ‘Every shell seemed either to burst right over the Ras-el-Tin works, or to pitch upon the very parapet of the Mex Fort upon the hill.’ It was just after this that Admiral Seymour signalled, ‘Well done, Inflexible!’ The Inflexible bore the brunt of the firing from the Ras-el-Tin batteries for three and a half hours, until she had silenced the Egyptian guns. After that, with the aid of the Téméraire, she silenced the Lighthouse Fort and Fort Adda, the front of which strongly fortified work her fire is said to have literally blown in.

It was on board the Inflexible also that the late Commander Younghusband performed an exploit of great daring—though only characteristic of the man, and of the spirit that has ever existed in the service to which he belonged. In the midst of the fighting the vent of one of the Inflexible’s 80-ton guns had become choked; with the result that for the time being the gun was completely out of action. Lieutenant Younghusband (as the gallant officer then was) calmly got inside the gun—a muzzle-loader—and caused himself to be rammed by the hydraulic rammer right up the bore of the gun (a tube 16 inches in diameter) until he reached the powder-chamber, when he managed with his fingers to remedy the defect, all the time at imminent risk of suffocation from the powder gases. When he had done his work, a rope fastened to his feet hauled him back and drew him out of the gun.

The Inflexible at Alexandria had numerous dents made in her armour, and the unarmoured part of the hull was pierced by shot in several places. Her most serious injury was from a 10-inch shell, which struck the ship below the water-line outside the central armoured ‘citadel,’ and, glancing up, passed through her decks, killing one of the men, and mortally wounding Lieutenant Francis Jackson as he was directing the fire of one of the light guns on the superstructure.

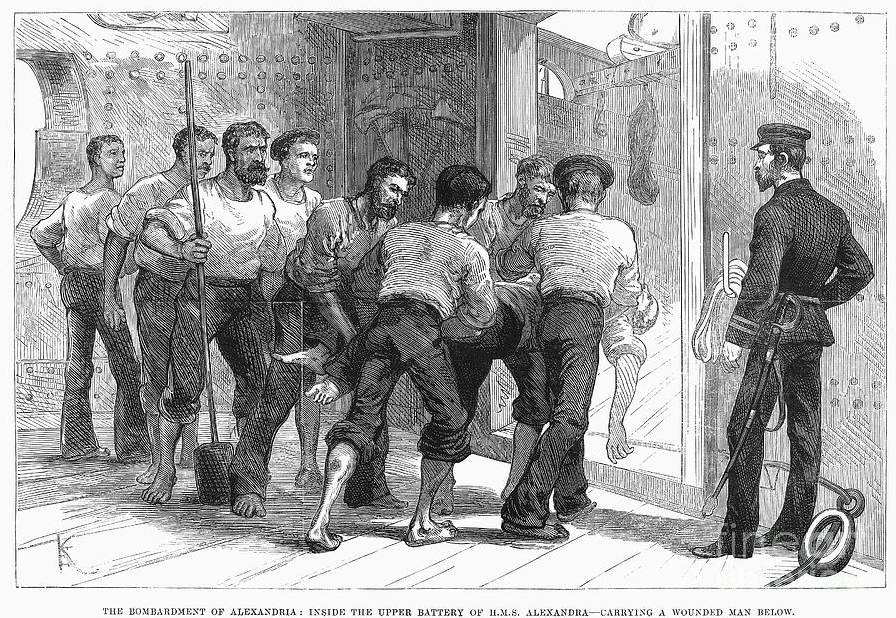

Her due, too, must be given to the ‘Old Alex,’ as the Navy used to call the favourite flagship of the Fleet during the closing years of Queen Victoria’s reign. On board the Alexandra (Captain C.F. Hotham) Mr. Israel Harding, the chief gunner of the ship, won the V.C. Just at ten o’clock, about three hours after the action began, a 10-inch spherical shell crashed through the Alexandra’s side, at a part where the ship was unarmoured, and with its fuse burning rolled along the main-deck. With great gallantry and presence of mind, Mr. Harding, who from below had heard the shout, ‘There’s a live shell just above the hatchway!’ rushed up the ladder, and taking some water from a tub near by, dashed it upon the burning fuse, after which he seized the shell and plunged it bodily into the tub, rendering it harmless. For this act of valour, which undoubtedly saved many lives, Mr. Harding was deservedly awarded the Victoria Cross. The shell was presented to His Majesty King Edward, then Prince of Wales. It was in the circumstances by no means an inappropriate presentation. The Alexandra was so named in honour of Her Majesty Queen Alexandra, then Princess of Wales, who launched the ship on an April day of the year 1875 that Chatham is not likely to forget. On the stocks, until a few days before she was sent afloat, the ship had been known as the Superb, and her re-naming as the Alexandra was meant as a special compliment to her royal sponsor, which met with universal applause. It drew forth, among other poetical tributes elsewhere, the following Latin verses in the Times:—

THE LAUNCH OF THE ALEXANDRA

Fulcra securifera fabri succidite dextra;

Omen habet primas si bene tangit aquas.

Dicite—Sit Felix—proraeque invergite vina;

Nomen Alexandrae dulce Superba tulit.

Nomine mutato, sit et omine fausta secundo;

Sit sine rivali, nec tamen ipsa ferox.

Jam neque tormentis opus est, nec triplice lamna,

Forma tumescentes sola serenat aquas.

Te capiente capi qui non velit ipse phaselus,

‘Ferreus, et verè ferreus iste fuit.’

To add to the éclat of the Alexandra’s launch, the Archbishop of Canterbury (Dr. Tait), with the Bishop of Rochester, conducted the religious service on the occasion—the first time that a religious service of any kind had been used at the launch of a British man-of-war since the Reformation. To Queen Alexandra we owe the restoration of the ancient usage of invoking, at the outset of their existence, the protection of Almighty God on the ships by which our homes and our Empire are guarded, and also on those who are to man them; and the practice, so instituted, has continued to be observed at the launches of all British men-of-war, ever since the launch of the Alexandra.

The Alexandra came out of action after the bombardment of Alexandria with twenty-four hits from shot or shell on the hull outside the armour-plating, and with several dents in her armour, one of her funnels damaged, and her rigging a good deal cut about. Most of the enemy’s shots, fortunately, had been aimed too high.

The Invincible (Captain R.H. More-Molyneux), on board which ship Sir Beauchamp Seymour had his flag for the day,—the Alexandra was really his flagship, but he had removed into the Invincible a short time before because of her lighter draught in order to enter the harbour,—had also numerous dents in her armour near the water-line, and the unarmoured parts of her hull had holes through it in several places. Her part in the fighting was for most of the time at anchor off Fort Mex, and the precision of her firing was enthusiastically applauded by the officers of the American ships who watched it from the offing. It was from the Invincible that the landing-party of four officers and twelve men—all volunteers—went off, towards the close of the action, to disable the guns of Fort Mex. The duty was an extremely dangerous one. There was no means of knowing what troops the enemy might not have under cover close behind the fort. To effect their landing the little party—the officers were Lieutenants Barton Bradford and Poore, Flag-Lieutenant Lambton, and Major Tulloch of the Welsh Regiment (Military Staff Officer to the Admiral)—had to swim through the surf. No opposition, however, met them, and after bursting the guns with charges of gun-cotton the party returned on board without a casualty.

Less is on record about what took place on board the other ships. All did their duty, and it was not their fault that no chances of special distinction came their way. The Superb (Captain T. Le H. Warde) was hit badly near the water-line, just above the armour-belt, by a shell that shattered a hole in the hull 10 feet long by 4 feet wide. One shot made a hole, 10 inches across, in the fore part of the ship near one of her torpedo-ports, and another a hole, a foot across, a little aft of her battery; besides which her armour was dented and her foremast shot through. The Sultan (Captain W.J. Hunt-Grubbe, C.B., A.D.C.) had an armour-plate on the water-line dented and ‘started,’ four boats damaged, and one funnel shot through. The Penelope (Captain St. G.C. d’Arcy-Irvine) was hulled eight times, and one of her guns had its muzzle chipped. The Téméraire and Monarch (Captains H.F. Nicholson and H. Fairfax, C.B., A.D.C.)—though the value of the work they did and the way they were handled were second to none—came out of action with little or no damage to report.

Always loved a good tale of sea-faring daring-do, and that is one right up there. A good choice.

The real men of war in history have stories every bit as good as any writer could dream up.