Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Wonderful Stories: Winning the V.C. in the Great War (published 1918).

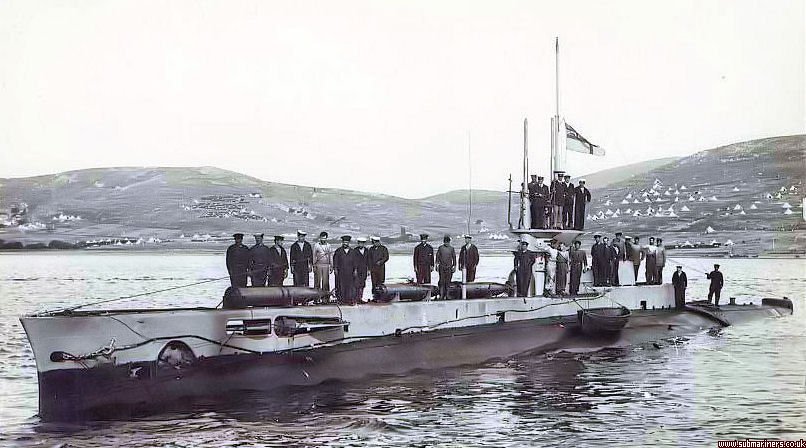

When, in December, 1914, Lieutenant Norman Holbrook, V.C., crept up the Dardanelles in B11 and sank the Turkish battleship Messoudieh at her moorings, he set an example which every officer and man in the submarine service was keen to follow. There was great competition among commanding officers for the honour and the opportunities afforded in this theatre of war, but the authorities had perforce to select some of our largest and best boats for this work. Lieut. Holbrook was fortunate, inasmuch as he was already stationed in the Mediterranean with his little 316-ton submarine when the war broke out; but the vessels subsequently sent from England were mainly of the “E” class, displacing about 800 tons, and having engines three times as powerful as the “B” class for surface work, and five times in the submerged condition.

One of the earliest of the “E” boats to win distinction was the E14, a vessel completed by Messrs. Vickers soon after the outbreak of war, and dispatched at once to the Eastern Mediterranean under the orders of Lieutenant-Commander Edward Courtney Boyle. This officer had already been mentioned in dispatches for his observation work off the German coast in the opening days of the war, his command then being submarine D3; but he was to do far greater things with E14.

On April 27th, 1915, he left the main body of the fleet and made for the Dardanelles. In the four months that had elapsed since the B11 had achieved such a brilliant coup the Turks had greatly improved the anti-submarine defences of the narrow channel. The submerged mine-fields had been increased in numbers and efficiency; in certain parts of the Straits old hulks had been sunk in order to impede the progress of our submarines, while guns had been mounted in favourable positions ashore for covering any vessel that happened by this means to be compelled to rise to the surface.

The enemy had also organized a system of patrols, a number of small vessels being apportioned to each two or three miles of the channel, to guard it against the passage of submarines. Appropriately enough, it was one of these very ships that the E14 secured as her first victim. The Dardanelles are so narrow, and the current that sweeps through them from the Sea of Marmara to the Mediterranean so strong, that a submarine is bound to rise at more or less frequent intervals, in order to verify her course and avoid running into the banks on either side. Lieut.-Commander Boyle had set out with the intention of first getting into the Sea of Marmara, and then settling down to work when he got there; but, coming up on one occasion to take his bearings, he saw, by means of the periscope, the reflected image of a Turkish gunboat not many hundred yards distant.

Now, a periscope was the very thing that the gunboat had been set to look out for, and the Turks who failed to see it had no one but themselves to blame for what followed. Lieut.-Commander Boyle, intently studying the surrounding area of water reflected on to the screen below, gently edged his vessel round until she was aiming straight at the hapless Turkish gunboat. A couple of brisk orders, and 300 lb. of guncotton was tearing towards the enemy at the rate of 35 miles an hour, eight or nine feet beneath the surface of the water.

In a few seconds the submarine rocked to a terrific explosion as the torpedo reached its target. Those of the British vessel’s crew who could be spared from their stations hurried along for a periscope-glance at the sinking gunboat; and then, remaining only long enough to assure himself of the enemy’s fate, Lieut.-Commander Boyle dived his vessel and waited at a safe depth until the hubbub on the surface had subsided. Then he proceeded on his journey, leaving the Turkish navy the poorer by a vessel — either the Berk-i-Satvet or a sister ship — of 740 tons, built in Germany in 1907, and carrying a crew of 120 men.

This was an excellent beginning, but more important successes were yet to be achieved.

Entering the Sea of Marmara, Lieut.-Commander Boyle was compelled to use the utmost caution, for the news of his coming had preceded him, and the anti-submarine patrol, maintained by destroyers, torpedo-boats, gunboats and armed auxiliaries, was being pursued with the utmost determination, sometimes compelling the E14 to remain totally submerged for twelve hours at a stretch. On April 29th, however, she “bagged” her second victim— this time a Turkish transport; though whether she had troops on board at the time, or was returning more or less empty, after carrying them across to the Asiatic side, is not known.

Four days later she repeated her success of April 27th, stalking and sinking one of the vessels specially deputed to get rid of her. The Turkish fleet comprised such a miscellaneous collection of ships of all ages and sizes that this was one of the many that our officers were unable to identify, and in the case of a submarine, it is, of course, quite impossible for the attacking vessel to stand by and pick up survivors, and learn the vessel’s name in that way.

After this, the hunt became so hot that the E14 had to make herself scarce, though she was still able to cruise about in the less frequented parts of the sea, and pick up a good deal of useful information. For a week no favourable opportunity of using her torpedoes presented itself, but on May 10th came the greatest success of all. What the Admiralty described as “a very large transport, full of troops,” was sighted not very long after she left Constantinople. The sinking of transports laden with more or less helpless soldiers is not one of the nicest refinements of twentieth century warfare, but it stands in principle on the same basis as the mining of an enemy trench, and its legitimacy is, of course, fully recognized even by those who most deplore it. Consequently, when Lieut.-Commander Boyle found this transport, without convoy, carrying soldiers into the fighting line against British, French and Russian troops, he had no doubts whatever as to his duty. He took up his position at right angles to the course of the transport and waited; and when the right moment came the torpedo was released.

As there were no other hostile ships in sight, the E14 came to the surface. The transport was already settling down when our men emerged from the hatch of the conning tower on to the deck, and doubtless a large number of men had been killed by the torpedo’s explosion.

Others, however, had succeeded in launching boats and rafts, and these, of course, were not interfered with, though German submarines in similar circumstances had not hesitated to fire on innocent civilians. The submarine remained for some time on the surface; and when the approach of hostile torpedo-craft warned her that it was time to submerge, the transport had already disappeared. How many men went down with her only the Turks know.

The E14 remained in the Sea of Marmara another eight days after this, and on May 13th, while cruising on the surface, forced a small enemy steamer — probably carrying munitions of war — to run herself ashore in order to avoid being torpedoed. On May 18th the submarine slipped back again into the Dardanelles, and within a few hours was past all dangers and back into the open Mediterranean. As a mere record of work done, her performance was a great one, but we shall fail to realize it to the full unless we remember that for three weeks she had been operating single-handed in an area only 175 miles long and 50 miles across at its widest part, its waters constantly scoured by hostile warships in search of submarines, and every inch of its shores in the possession of the enemy.

Within a few days after the E14’s return, it was announced that the King had been pleased to award the Victoria Cross to her commanding officer; that the Distinguished Service Cross was awarded to Lieut. E. G. Stanley and to Acting- Lieut. R. W. Lawrence, of the Royal Naval Reserve, and that each member of the crew had been granted the Distinguished Service Medal. The official statement issued by the Admiralty recorded the report of Vice-Admiral de Robeck, commander-in-chief in the Eastern Mediterranean, that it was “impossible to do full justice to this great achievement, and that his Majesty the King’s appreciation and reward for these services have throughout the Allied Fleets given universal satisfaction.”