Editor’s note: Here follows the seventh chapter of The Story of the Malakand Field Force: An Episode of Frontier War, by Winston S. Churchill (published 1898). All spelling in the original.

CHAPTER VII: THE GATE OF SWAT

The Malakand Pass gives access to the valley of the Swat, a long and wide trough running east and west, among the mountains. Six miles further to the east, at Chakdara, the valley bifurcates. One branch runs northward towards Uch, and, turning again to the west, ultimately leads to the Panjkora River and beyond to the great valley of Nawagai. For some distance along this branch lies the road to Chitral, and along it the Malakand Field Force will presently advance against the Mohmands. The other branch prolongs the valley to the eastward. A few miles beyond Chakdara a long spur, jutting from the southern mountains, blocks the valley. Round its base the river has cut a channel. The road passes along a narrow stone causeway between the river and the spur. Here is the Landakai position, or as the tribesmen have for centuries called it, the “Gate of Swat.” Beyond this gate is Upper Swat, the ancient, beautiful and mysterious “Udyana.” This chapter will describe the forcing of the gate and the expedition to the head of the valley.

The severe fighting at the Malakand and Chakdara had shown how formidable was the combination, which had been raised against the British among the hill tribes. The most distant and solitary valleys, the most remote villages, had sent their armed men to join in the destruction of the infidels. All the Banjaur tribes had been well represented in the enemy’s ranks. The Bunerwals and the Utman Khels had risen to a man. All Swat had been involved. Instead of the two or three thousand men that had been estimated as the extreme number, who would follow the Mad Fakir, it was now known that over 12,000 were in arms. In consequence of the serious aspect which the military and political situation had assumed, it was decided to mobilise a 3rd and Reserve Brigade composed as follows:—

3rd Brigade.

Commanding—Brigadier-General J.H. Wodehouse, C.B., C.M.G.

2nd Battalion Highland Light Infantry.

1st " Gordon Highlanders.

21st Punjaub Infantry.

2nd Battalion 1st Gurkhas.

No. 3 Company Bombay Sappers and Miners.

" 14 British Field Hospital.

" 45 Native " "

" 1 Field Medical Depot.

The fighting of the preceding fortnight had left significant and terrible marks on the once smiling landscape. The rice crops were trampled down in all directions. The ruins of the villages which had been burned looked from a distance like blots of ink. The fearful losses which the enemy had sustained, had made an appreciable diminution, not of an army, but of a population. In the attacks upon the Malakand position, about 700 tribesmen had perished. In the siege of Chakdara, where the open ground had afforded opportunity to the modern weapons and Maxim guns, over 2000 had been killed and wounded. Many others had fallen in the relief of Chakdara and in the cavalry pursuit. For days their bodies lay scattered about the country. In the standing crops, in the ruins of villages, and among the rocks, festering bodies lay in the blazing sun, filling the valley with a dreadful smell. To devour these great numbers of vultures quickly assembled and disputed the abundant prey with the odious lizards, which I have mentioned in an earlier chapter, and which emerged from holes and corners to attack the corpses. Although every consideration of decency and health stimulated the energy of the victors in interring the bodies of their enemies, it was some days before this task could be accomplished, and even then, in out-of-the-way places, there remained a good many that had escaped the burying parties.

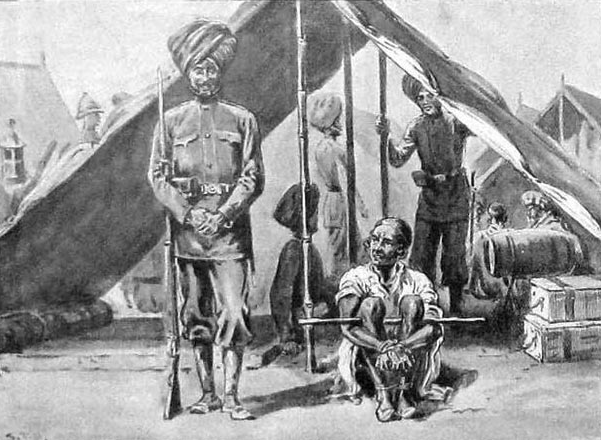

Meanwhile the punishment that the tribesmen of the Swat Valley had received, and their heavy losses, had broken the spirit of many, and several deputations came to make their submission. The Lower Swatis surrendered unconditionally, and were allowed to return to their villages. Of this permission they at once availed themselves, and their figures could be seen moving about their ruined homes and endeavouring to repair the damage. Others sat by the roadside and watched in sullen despair the steady accumulation of troops in their valley, which had been the only result of their appeal to arms.

It is no exaggeration to say, that perhaps half the tribesmen who attacked the Malakand, had thought that the soldiers there, were the only troops that the Sirkar [The Government] possessed. “Kill these,” they said, “and all is done.” What did they know of the distant regiments which the telegraph wires were drawing, from far down in the south of India? Little did they realise they had set the world humming; that military officers were hurrying 7000 miles by sea and land from England, to the camps among the mountains; that long trains were carrying ammunition, material and supplies from distant depots to the front; that astute financiers were considering in what degree their action had affected the ratio between silver and gold, or that sharp politicians were wondering how the outbreak in Swat might be made to influence the impending bye-elections. These ignorant tribesmen had no conception of the sensitiveness of modern civilisation, which thrills and quivers in every part of its vast and complex system at the slightest touch.

They only saw the forts and camps on the Malakand Pass and the swinging bridge across the river.

While the people of Lower Swat, deserted by the Mad Mullah, and confronted with the two brigades, were completely humbled and subdued, the Upper Swatis, encouraged by their priests, and, as they believed, safe behind their “gate,” assumed a much more independent air. They sent to inquire what terms the Government would offer, and said they would consider the matter. Their contumacious attitude, induced the political officers to recommend the movement of troops through their country, to impress them with the determination and power of the Sirkar.

The expedition into the Upper Swat Valley was accordingly sanctioned, and Sir Bindon Blood began making the necessary preparations for the advance. The prospects of further fighting were eagerly welcomed by the troops, and especially by those who had arrived too late for the relief of Chakdara, and had had thus far, only long and dusty marches to perform. There was much speculation and excitement as to what units would be selected, every one asserting that his regiment was sure to go; that it was their turn; and that if they were not taken it would be a great shame.

Sir Bindon Blood had however already decided. He had concentrated a considerable force at Amandara in view of a possible advance, and as soon as the movement was sanctioned organised the column as follows:—

1st Brigade.

Commanding—Brigadier-General Meiklejohn.

Royal West Kent Regiment.

24th Punjaub Infantry.

31st " "

45th Sikhs

With the following divisional troops:—

10th Field Battery.

No.7 British Mountain Battery.

" 8 Bengal " "

" 5 Company Madras Sappers and Miners.

2 Squadrons Guides Cavalry.

4 " 11th Bengal Lancers.

This force amounted to an available fighting strength of 3500 rifles and sabres, with eighteen guns. Supplies for twelve days were carried, and the troops proceeded on “the 80 lb. scale” of baggage, which means, that they did not take tents, and a few other comforts and conveniences.

Before the force started, a sad event occurred. On the 12th of August, Lieut.-Colonel J. Lamb, who had been wounded on the night of the 26th of July, died. An early amputation might have saved his life; but this was postponed in the expectation that the Rontgen Rays would enable the bullet to be extracted. The Rays arrived from India after some delay. When they reached Malakand, the experiment was at once made. It was found, however, that the apparatus had been damaged in coming up, and no result was obtained. Meanwhile mortification had set in, and the gallant soldier died on the Sunday, from the effects of an amputation which he was then too weak to stand. His thigh bone had been completely shattered by the bullet. He had seen service in Afghanistan and the Zhob Valley and had been twice mentioned in despatches.

On the 14th Sir Bindon Blood joined the special force, and moved it on the 16th to Thana, a few miles further up the valley. At the same time he ordered Brigadier-General Wodehouse to detach a small column in the direction of the southern passes of Buner. The Highland Light Infantry, No.3 Company Bombay Sappers and Miners, and one squadron of the 10th Bengal Lancers accordingly marched from Mardan, where the 3rd Brigade then was, to Rustum. By this move they threatened the Bunerwals and distracted their attention from the Upper Swat Valley. Having thus weakened the enemy, Sir Bindon Blood proceeded to force the “Gate of Swat.”

On the evening of the 16th, a reconnaissance by the 11th Bengal Lancers, under Major Beatson, revealed the fact, that the Landakai position was strongly held by the enemy. Many standards were displayed, and on the approach of the cavalry, shots were fired all along the line. The squadron retired at once, and reported the state of affairs. The general decided to attack at day-break.

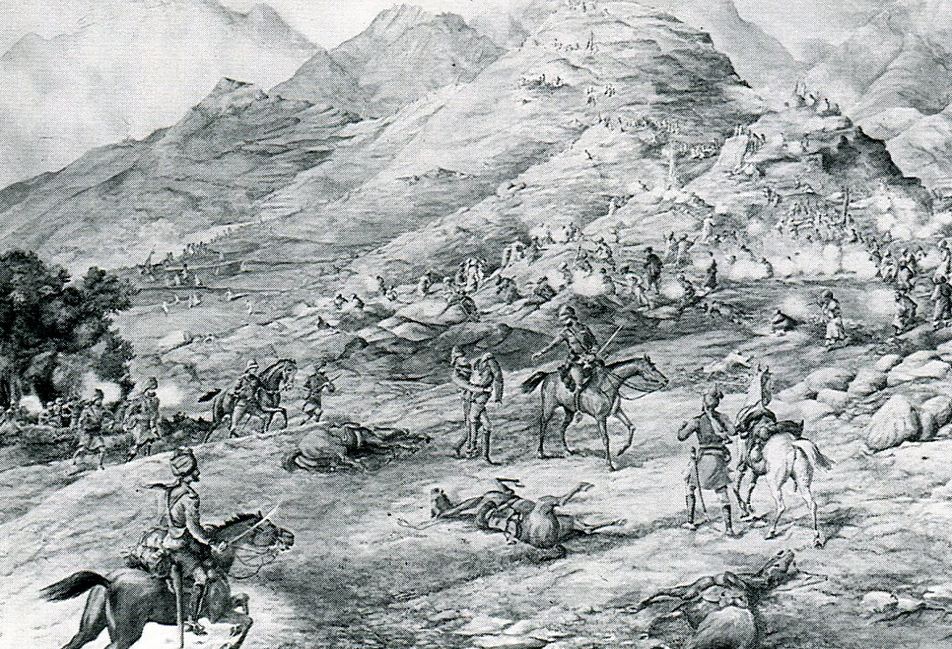

At 6.30 A.M. on the 17th, the cavalry moved off, and soon came in contact with the tribesmen in some Buddhist ruins near a village, called Jalala. A skirmish ensued. Meanwhile the infantry were approaching. The main position of the enemy was displayed. All along the crest of the spur of Landakai could be seen a fringe of standards, dark against the sky. Beneath them the sword blades of the tribesmen glinted in the sunlight. A long line of stone sungars crowned the ridge, and behind the enemy clustered thickly. It is estimated that over 5000 were present.

It is not difficult to realise what a strong position this was. On the left of the troops was an unfordable river. On their right the mountains rose steeply. In front was the long ridge held by the enemy. The only road up the valley was along the causeway, between the ridge and the river. To advance further, it was necessary to dislodge the enemy from the ridge. Sir Bindon Blood rode forward, reconnoitered the ground, and made his dispositions.

To capture the position by a frontal attack would involve heavy loss. The enemy were strongly posted, and the troops would be exposed to a heavy fire in advancing. On the other hand, if the ridge could once be captured, the destruction of the tribesmen was assured. Their position was good, only as long as they held it. The moment of defeat would be the moment of ruin. The reason was this. The ground behind the ridge was occupied by swampy rice fields, and the enemy could only retire very slowly over it. Their safe line of retreat lay up the spur, and on to the main line of hills. They were thus formed with their line of retreat in prolongation of their front. This is, of course, tactically one of the worst situations that people can get into.

Sir Bindon Blood, who knew what the ground behind the ridge was like, perceived at once how matters stood, and made his plans accordingly. He determined to strike at the enemy’s left, thus not only turning their flank, but cutting off their proper line of retreat. If once his troops held the point, where the long ridge ran into the main hills, all the tribesmen who had remained on the ridge would be caught. He accordingly issued orders as follows:—

The Royal West Kent were to mask the front and occupy the attention of the enemy. The rest of the infantry, viz., 24th and 31st Punjaub Infantry and the 45th Sikhs, were to ascend the hills to the right, and deliver a flank attack on the head of the ridge. The cavalry were to be held in readiness to dash forward along the causeway—to repair which a company of sappers was posted—as soon as the enemy were driven off the ridge which commanded it, and pursue them across the rice fields into the open country beyond. The whole of the powerful artillery was to come into action at once.

The troops then advanced. The Royal West Kent Regiment began the fight, by driving some of the enemy from the Buddhist ruins on a small spur in advance of the main position. The 10th Field Battery had been left in rear in case the guns might stick in the narrow roads near Thana village. It had, however, arrived safely, and now trotted up, and at 8.50 A.M. opened fire on the enemy’s position and at a stone fort, which they occupied strongly. A few minutes later No.7 Mountain Battery came into action from the spur, which the Royal West Kent had taken. A heavy artillery fire thus prepared the way for the attack. The great shells of the Field Artillery astounded the tribesmen, who had never before witnessed the explosion of a twelve-pound projectile. The two mountain batteries added to their discomfiture. Many fled during the first quarter of an hour of the bombardment. All the rest took cover on the reverse slope and behind their sungars.

Meanwhile the flank attack was developing. General Meiklejohn and his infantry were climbing up the steep hillside, and moving steadily towards the junction of the ridge with the main hill. At length the tribesmen on the spur perceived the danger that was threatening them. They felt the grip on their line of retreat. They had imagined that the white troops would try and force their path along the causeway, and had massed considerable reserves at the lower end of the ridge. All these now realised that they were in great danger of being cut off. They were on a peninsula, as it were, while the soldiers were securing the isthmus. They accordingly began streaming along the ridge towards the left, at first with an idea of meeting the flank attack, but afterwards, as the shell fire grew hotter, and the musketry increased, only in the hope of retreat. Owing to the great speed with which the mountaineers move about the hills, most of them were able to escape before the flank attack could cut them off. Many however, were shot down as they fled, or were killed by the artillery fire. A few brave men charged the 31st Punjaub Infantry, but were all destroyed.

Seeing the enemy in full flight, Sir Bindon Blood ordered the Royal West Kent to advance against the front of the now almost deserted ridge. The British infantry hurrying forward climbed the steep hill and captured the stone sungars. From this position they established touch with the flank attack, and the whole force pursued the flying tribesmen with long-range fire.

The “Gate of Swat” had been forced. It was now possible for troops to advance along the causeway. This had, however, been broken in various places by the enemy. The sappers and miners hastened forward to repair it. While this was being done, the cavalry had to wait in mad impatience, knowing that their chance lay in the plains beyond. As soon as the road was sufficiently repaired to allow them to pass in single file, they began struggling along it, and emerged at the other end of the causeway in twos and threes.

An incident now ensued, which, though it afforded an opportunity for a splendid act of courage, yet involved an unnecessary loss of life, and must be called disastrous. As the cavalry got clear of the broken ground, the leading horsemen saw the tribesmen swiftly running towards the hills, about a mile distant. Carried away by the excitement of the pursuit, and despising the enemy for their slight resistance, they dashed impetuously forward in the hope of catching them before they could reach the hills.

Lieutenant-Colonel Adams, on entering the plain, saw at once that if he could seize a small clump of trees near a cemetery, he would be able to bring effective dismounted fire to bear on the retreating tribesmen. He therefore collected as many men as possible, and with Lieutenant Maclean, and Lord Fincastle, the Times correspondent, rode in the direction of these points. Meanwhile Captain Palmer, who commanded the leading squadron, and Lieutenant Greaves of the Lancashire Fusiliers, who was acting war correspondent of the Times of India, galloped across the rice fields after the enemy. The squadron, unable to keep up, straggled out in a long string, in the swampy ground.

At the foot of the hills the ground was firmer, and reaching this, the two officers recklessly dashed in among the enemy. It is the spirit that loses the Empire many lives, but has gained it many battles. But the tribesmen, who had been outmanoeuvred rather than outfought, turned savagely on their pursuers. The whole scene was witnessed by the troops on the ridge. Captain Palmer cut down a standard-bearer. Another man attacked him. Raising his arm for a fresh stroke, his wrist was smashed by a bullet. Another killed his horse. Lieutenant Greaves, shot through the body, fell at the same moment to the ground. The enemy closed around and began hacking him, as he lay, with their swords. Captain Palmer tried to draw his revolver. At this moment two sowars got clear of the swampy rice fields, and at once galloped, shouting, to the rescue, cutting and slashing at the tribesmen. All would have been cut to pieces or shot down. The hillside was covered with the enemy. The wounded officers lay at the foot. They were surrounded. Seeing this Lieutenant-Colonel Adams and Lord Fincastle, with Lieutenant Maclean and two or three sowars, dashed to their assistance. At their charge the tribesmen fell back a little way and opened a heavy fire. Lord Fincastle’s horse was immediately shot and he fell to the ground. Rising, he endeavoured to lift the wounded Greaves on to Colonel Adams’ saddle, but at this instant a second bullet struck that unfortunate officer, killing him instantly. Colonel Adams was slightly, and Lieutenant Maclean mortally, wounded while giving assistance, and all the horses but two were shot. In spite of the terrible fire, the body of Lieutenant Greaves and the other two wounded officers were rescued and carried to the little clump of trees.

For this gallant feat of arms both the surviving officers, Colonel Adams and Lord Fincastle, were recommended for, and have since received, the Victoria Cross. It was also officially announced, that Lieutenant Maclean would have received it, had he not been killed. There are many, especially on the frontier, where he was known as a fine soldier and a good sportsman, who think that the accident of death should not have been allowed to interfere with the reward of valour.

The extremes of fortune, which befell Lord Fincastle and Lieutenant Greaves, may well claim a moment’s consideration. Neither officer was employed officially with the force. Both had travelled up at their own expense, evading and overcoming all obstacles in an endeavour to see something of war. Knights of the sword and pen, they had nothing to offer but their lives, no troops to lead, no duties to perform, no watchful commanding officer to report their conduct. They played for high stakes, and Fortune never so capricious as on the field of battle, dealt to the one the greatest honour that a soldier can hope for, as some think, the greatest in the gift of the Crown, and to the other Death.

The flight of the enemy terminated the action of Landakai. Thus in a few hours and with hardly any loss, the “Gate of Swat,” which the tribesmen had regarded as impregnable, had been forced. One squadron of the Guides cavalry, under Captain Brasier Creagh, pursuing the enemy had a successful skirmish near the village of Abueh, and returned to camp about 6.30 in the evening. [This officer was mentioned in despatches for his skill and judgment in this affair; but he is better known on the frontier for his brilliant reconnaissance towards Mamani, a month later, in which in spite of heavy loss he succeeded in carrying out General Hammond’s orders and obtained most valuable information.] During the fight about 1000 tribesmen had threatened the baggage column, but these were but poor-spirited fellows, for they retired after a short skirmish with two squadrons of the 11th Bengal Lancers, with a loss of twenty killed and wounded. The total casualties of the day were as follows:—

BRITISH OFFICERS.

Killed—Lieutenant R.T. Greaves, Lancs. Fusiliers.

" " H.L.S. Maclean, Guides.

Wounded severely—Captain M.E. Palmer, Guides.

Wounded slightly—Lieutenant-Colonel R.B. Adams, Guides.

NATIVE RANKS—Wounded—5.

FOLLOWERS—Wounded—2.

Total Casualties—11.

It must be remembered, that but for the incident which resulted in the deaths of the officers, and which Sir Bindon Blood described in his official despatch as an “unfortunate contretemps,” the total casualties would have only been seven wounded. That so strong a position should have been captured with so little loss, is due, firstly, to the dispositions of the general; and secondly, to the power of the artillery which he had concentrated. The account of the first attempt to storm the Dargai position on the 20th of October, before it had been shaken by artillery fire, when the Dorsetshire Regiment suffered severe loss, roused many reflections among those who had witnessed the action of Landakai.

The next morning, the 18th, the force continued their march up the valley of the Upper Swat. The natives, thoroughly cowed, offered no further opposition and sued for peace. Their losses at Landakai were ascertained to have exceeded 500, and they realised that they had no chance against the regular troops, when these were enabled to use their powerful weapons.

As the troops advanced up the fertile and beautiful valley, all were struck by the numerous ruins of the ancient Buddhists. Here in former times were thriving cities, and civilised men. Here, we learn from Fa-hien, [Record Of Buddhistic Kingdoms. Translated by James Legge, M.A., LL.D.] were “in all 500 Sangharamas,” or monasteries. At these monasteries the law of hospitality was thus carried out: “When stranger bhikshus (begging monks) arrive at one of them, their wants are supplied for three days, after which they are told to find a resting-place for themselves.” All this is changed by time. The cities are but ruins. Savages have replaced the civilised, bland-looking Buddhists, and the traveller who should apply for hospitality, would be speedily shown “a resting-place,” which would relieve his hosts from further trouble concerning him.

“There is a tradition,” continues the intrepid monk, who travelled through some of the wildest countries of the earth in the darkest ages of its history, “that when Buddha came to North India, he came to this country, and that he left a print of his foot, which is long or short according to the ideas of the beholder.” Although the learned Fa-hien asserts that “it exists, and the same thing is true about it at the present day,” the various cavalry reconnaissances failed to discover it, and we must regretfully conclude that it has also been obliterated by the tides of time. Here too, says this Buddhistic Baedeker, is still to be seen the rock on which “He dried his clothes; and the place where He converted the wicked dragon (Naga).” “The rock is fourteen cubits high and more than twenty broad, with one side of it smooth.” This may well be believed; but there are so many rocks of all dimensions that the soldiers were unable to make certain which was the scene of the dragon’s repentance, and Buddha’s desiccation.

His companions went on ahead towards Jellalabad, or some city in that locality, but Fa-hien, charmed with the green and fertile beauties of “the park,” remained in the pleasant valley and “kept the summer retreat.” Then he descended into the land of So-hoo-to, which is perhaps Buner.

Even in these busy, practical, matter-of-fact, modern times, where nothing is desirable unless economically sound, it is not unprofitable for a moment to raise the veil of the past, and take a glimpse of the world as it was in other days. The fifth century of the Christian era was one of the most gloomy and dismal periods in the history of mankind. The Great Roman Empire was collapsing before the strokes of such as Alaric the Goth, Attila the Hun, and Genseric the Vandal. The art and valour of a classical age had sunk in that deluge of barbarism which submerged Europe. The Church was convulsed by the Arian controversy. That pure religion, which it should have guarded, was defiled with the blood of persecution and degraded by the fears of superstition. Yet, while all these things afflicted the nations of the West, and seemed to foreshadow the decline or destruction of the human species, the wild mountains of Northern India, now overrun by savages more fierce than those who sacked Rome, were occupied by a placid people, thriving, industrious, and intelligent; devoting their lives to the attainment of that serene annihilation which the word nirvana expresses. When we reflect on the revolutions which time effects, and observe how the home of learning and progress changes as the years pass by, it is impossible to avoid the conclusion, perhaps a mournful one, that the sun of civilisation can never shine all over the world at once.

On the 19th, the force reached Mingaora, and here for five days they waited in an agreeable camp, to enable Major Deane to receive the submission of the tribes. These appeared much humbled by their defeats, and sought to propitiate the troops by bringing in supplies of grain and forage. Over 800 arms of different descriptions were surrendered during the halt. A few shots were fired into the camp on the night of the arrival at Mingaora, but the villagers, fearing lest they should suffer, turned out and drove the “snipers” away. On the 21st a reconnaissance as far as the Kotke Pass afforded much valuable information as to the nature of the country. All were struck with the beauty of the scenery, and when on the 24th the force marched back to Barikot, they carried away with them the memory of a beautiful valley, where the green of the rice fields was separated from the blue of the sky by the glittering snow peaks of the Himalayas.

While the troops rested at Barikot, Sir Bindon Blood personally reconnoitred the Karakar Pass, which leads from the Swat Valley into the country of the Bunerwals. The Bunerwals belong to the Yusaf section, of the Yusafzai tribe. They are a warlike and turbulent people. To their valley, after the suppression of the Indian Mutiny, many of the Sepoys and native officers who had been in revolt fled for refuge. Here, partly by force and partly by persuasion, they established themselves. They married women of the country and made a settlement. In 1863 the Bunerwals came into collision with the British Government and much severe fighting ensued, known to history as the Ambeyla Campaign. The refugees from India renewed their quarrel with the white troops with eagerness, and by their extraordinary courage and ferocity gained the name of the “Hindustani Fanatics.” At the cost of thirty-six officers and eight hundred men Buner was subdued. The “Crag Picket” was taken for the last time by the 101st Fusiliers, and held till the end of the operations. Elephants, brought at great expense from India, trampled the crops. Most of the “Hindustani Fanatics” perished in the fighting. The Bunerwals accepted the Government terms, and the troops retired. Since then, in 1868, in 1877 and again in 1884 they raided border villages, but on the threat of an expedition paid a fine and made good the damage. The reputation they have enjoyed since their stout resistance in 1863, has enabled them to take a leading position among the frontier tribes; and they have availed themselves of this to foment and aggravate several outbreaks against the British. Their black and dark-blue clothes had distinguished them from the other assailants of Malakand and Chakdara. They had now withdrawn to their valley and thence defied the Government and refused all terms.

As Sir Bindon Blood and his escort approached the top of the pass, a few shots were fired by the watchers there, but there was no opposition. All the Bunerwals had hurried over to defend the southern entrances to their country, which they conceived were in danger of attack from Brigadier-General Wodehouse’s force at Rustum. The general reached the Kotal, and saw the whole valley beneath him. Great villages dotted the plains and the aspect was fertile and prosperous.

The unguarded Karakar Pass was practicable for troops, and if the Government would give their consent, Buner might be reduced in a fortnight without difficulty, almost without fighting.

Telegrams were despatched to India on the subject, and after much delay and hesitation the Viceroy decided against the recommendation of his victorious general. Though the desirability of settling with the Bunerwals was fully admitted, the Government shrank from the risk. The Malakand Field Force thus remained idle for nearly a fortnight. The news, that the Sirkar had feared to attack Buner, spread like wildfire along the frontier, and revived the spirits of the tribes. They fancied they detected a sign of weakness. Nor were they altogether wrong. But the weakness was moral rather than physical.

It is now asserted, that the punishment of Buner is only postponed, and that a few months may see its consummation. [Written in 1897.] The opportunity of entering the country without having to force the passes may not, however, recur.

On the 26th of August the force returned to Thana, and the expedition into Upper Swat terminated.

[The following is the most trustworthy estimate obtainable of loss of life among the tribesmen in the fighting in the Swat Valley from 26th July to 17th August. The figures include wounded, who have since died, and are more than double those killed outright in the actions:—

1. Lower Swat Pathans... 700 Buried in the graveyards.

2. Upper " " ... 600 " " " "

3. Buner proper . ... 500 " " " "

4. Utman Khel . ... 80

5. Yusafzai. . ... 50

6. Other tribes . ... 150

Total—2080.

1, 2 and 3 are the result of recent inquiry on the spot.

4, 5 and 6 are estimates based on native information.

The proportion of killed and died of wounds to wounded would be very high, as the tribes have little surgical or medical knowledge and refused all offers of aid. Assuming that only an equal number were wounded and recovered, the total loss would be approximately 4000. A check is obtained by comparing these figures with the separate estimates for each action:—

Malakand.... 700

Siege of Chakdara.. 2000

Relief " " .. 500

Action of Landakai.. 500

Total—3700.