Editor’s note: Here follows the fifth chapter of The Story of the Malakand Field Force: An Episode of Frontier War, by Winston S. Churchill (published 1898). All spelling in the original.

Chapter V: The Relief of Chakdara

While the events described in the last chapter had been watched with interest and attention in all parts of the world, they were the subject of anxious consultation in the Council of the Governor-General. It was only natural that the Viceroy, himself, should view with abhorrence the prospect of military operations on a large scale, which must inevitably lead to closer and more involved relations with the tribes of the Afghan border. He belonged to that party in the State which has clung passionately, vainly, and often unwisely to a policy of peace and retrenchment. He was supported in his reluctance to embark on warlike enterprises by the whole force of the economic situation. No moment could have been less fitting: no man more disinclined. That Lord Elgin’s Viceroyalty and the Famine year should have been marked by the greatest Frontier War in the history of the British Empire in India, vividly displays how little an individual, however earnest his motives, however great his authority, can really control the course of public affairs.

The Council were called upon to decide on matters, which at once raised the widest and most intricate questions of frontier policy; which might involve great expense; which might well influence the development and progress of the great populations committed to their charge. It would be desirable to consider such matters from the most lofty and commanding standpoints; to reduce detail to its just proportions; to examine the past, and to peer into the future. And yet, those who sought to look thus on the whole situation, were immediately confronted with the picture of the rock of Chakdara, fringed and dotted with the white smoke of musketry, encircled by thousands of fierce assailants, its garrison fighting for their lives, but confident they would not be deserted. It was impossible to see further than this. All Governments, all Rulers, meet the same difficulties. Wide considerations of principle, of policy, of consequences or of economics are brushed aside by an impetuous emergency. They have to decide off-hand. The statesman has to deal with events. The historian, who has merely to record them, may amuse his leisure by constructing policies, to explain instances of successful opportunism.

On the 30th of July the following order was officially published: “The Governor-General in Council sanctions the despatch of a force, to be styled the Malakand Field Force, for the purpose of holding the Malakand, and the adjacent posts, and of operating against the neighbouring tribes as may be required.”

The force was composed as follows:—

1st Brigade.

Commanding—Colonel W.H. Meiklejohn, C.B., C.M.G., with the local

rank of Brigadier-General.

1st Battalion Royal West Kent Regiment.

24th Punjaub Infantry.

31st Punjaub Infantry.

45th (Rattray's) Sikhs.

Sections A and B of No.1 British Field Hospital.

No.38 Native Field Hospital.

Sections A and B of No.50 Native Field Hospital.

2nd Brigade.

Commanding—Brigadier-General P.D. Jeffreys, C.B.

1st Battalion East Kent Regiment (the Buffs).

35th Sikhs.

38th Dogras.

Guides Infantry.

Sections C and D of No.1 British Field Hospital.

No.37 Native Field Hospital.

Sections C and D of No.50 Native Field Hospital.

Divisional Troops.

4 Squadrons 11th Bengal Lancers.

1 " 10th " "

2 " Guides Cavalry.

22nd Punjaub Infantry.

2 Companies 21st Punjaub Infantry.

10th Field Battery.

6 Guns No.1 British Mountain Battery.

6 " No.7 " " "

6 " No.8 Bengal " "

No.5 Company Madras Sappers and Miners.

No.3 " Bombay " " "

Section B of No.13 British Field Hospital.

Sections A and B of No.35 Native Field Hospital.

Line of Communications.

No.34 Native Field Hospital.

Section B of No.1 Native Field Hospital.

[This complete division amounted to a total available field strength of 6800 bayonets, 700 lances or sabres, with 24 guns.]

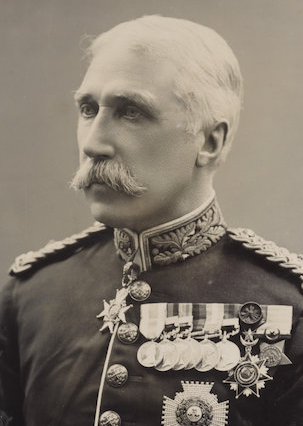

The command of this powerful force was entrusted to Brigadier-General Sir Bindon Blood, K.C.B., who was granted the local rank of Major-General.

As this officer is the principal character in the tale I have to tell, a digression is necessary to introduce him to the reader. Born of an old Irish family, a clan that has been settled in the west of Ireland for 300 years, and of which he is now the head, Sir Bindon Blood was educated privately, and at the Indian Military College at Addiscombe, and obtained a commission in the Royal Engineers in December, 1860. For the first eleven years he was stationed in England, and it was not until 1871 that he proceeded to India, where he first saw active service in the Jawaki Afridi Expedition (medal with clasp). In 1878 he returned home, but the next year was ordered to the Zulu War. On the conclusion of hostilities, for which he received a second medal and clasp, he again sailed for India and served throughout the Afghan war of 1880, being for some time with the troops at Cabul. In 1882 he accompanied the Army to Egypt, and was with the Highland Brigade, which was the most severely engaged at Tel-el-Kebir. He received the medal and clasp, Khedive’s star and the 3rd class of the Medjidie. After the campaign he went home for two years, and in 1885 made another voyage to the East, over which the Russian war-cloud was then hanging. Since then the general has served in India, at first with the Sappers and Miners, with whose reorganisation he was closely associated, and latterly in command of the Agra District. In 1895 he was appointed Chief of the Staff to Sir Robert Low in the Chitral Expedition, and was present at all the actions, including the storming of the Malakand Pass. For his services he received a degree of knighthood of the Military Order of the Bath and the Chitral medal and clasp. He was now marked as a man for high command on the frontier at the first opportunity. That opportunity the great rising of 1897 has presented.

Thirty-seven years of soldering, of war in many lands, of sport of every kind, have steeled alike muscle and nerve. Sir Bindon Blood, himself, till warned by the march of time, a keen polo player, is one of those few officers of high rank in the army, who recognise the advantages to soldiers of that splendid game. He has pursued all kinds of wild animals in varied jungles, has killed many pig with the spear and shot every species of Indian game, including thirty tigers to his own rifle.

It would not be fitting for me, a subaltern of horse, to offer any criticism, though eulogistic, on the commander under whom I have had the honour to serve in the field. I shall content myself with saying, that the general is one of that type of soldiers and administrators, which the responsibilities and dangers of an Empire produce, a type, which has not been, perhaps, possessed by any nation except the British, since the days when the Senate and the Roman people sent their proconsuls to all parts of the world.

Sir Bindon Blood was at Agra, when, on the evening of the 28th of July, he received the telegram from the Adjutant-General in India, appointing him to the command of the Malakand Field Force, and instructing him to proceed at once to assume it. He started immediately, and on the 31st formally took command at Nowshera. At Mardan he halted to make arrangements for the onward march of the troops. Here, at 3 A.M. on the 1st of August, he received a telegram from Army Headquarters informing him, that Chakdara Fort was hard pressed, and directing him to hurry on to Malakand, and attempt its relief at all costs. The great numbers of the enemy, and the shortness of ammunition and supplies from which the garrison were suffering, made the task difficult and the urgency great. Indeed I have been told, that at Simla on the 1st of August it was feared, that Chakdara was doomed, and that sufficient troops to fight their way to its relief could not be concentrated in time. The greatest anxiety prevailed. Sir Bindon Blood replied telegraphically that “knowing the ground” as he did, he “felt serenely confident.” He hurried on at once, and, in spite of the disturbed state of the country, reached the Malakand about noon on the 1st of August.

The desperate position of the garrison of Chaldara was fully appreciated by their comrades at the Malakand. As the night of the 31st had been comparatively quiet, Brigadier-General Meiklejohn determined to attempt to force his way to their relief the next day. He accordingly formed a column as follows:—

45th Sikhs.

24th Punjaub Infantry.

No.5 Company Sappers and Miners.

4 Guns of No.8 Mountain Battery.

At 11 A.M. he sent the cavalry, under Lieutenant-Colonel Adams of the Guides, to make a dash for the Amandara Pass, and if it were unoccupied to seize it. The three squadrons started by the short road to the north camp. As soon as the enemy saw what was going on, they assembled in great numbers to oppose the advance. The ground was most unsuitable for cavalry. Great boulders strewed the surface. Frequent nullahs intersected the plain, and cramped the action of the horsemen. The squadrons soon became hotly engaged. The Guides made several charges. The broken nature of the ground favoured the enemy. Many of them were, however, speared or cut down. In one of these charges Lieutenant Keyes was wounded. While he was attacking one tribesman, another came up from behind, and struck him a heavy blow on the shoulder with a sword. Though these Swatis keep their swords at razor edge, and though the blow was sufficiently severe to render the officer’s arm useless for some days, it raised only a thin weal, as if from a cut of a whip. It was a strange and almost an inexplicable escape.

The enemy in increasing numbers pressed upon the cavalry, who began to get seriously involved. The tribesmen displayed the greatest boldness and determination. At length Lieut.-Colonel Adams had to order a retirement. It was none too soon. The tribesmen were already working round the left flank and thus threatening the only line of retreat. The squadrons fell back, covering each other by dismounted fire. The 24th Punjaub Infantry protected their flank as they reached the camp. The cavalry losses were as follows:—

BRITISH OFFICERS.

Wounded severely—Captain G.M. Baldwin, the Guides.

" slightly—Lieutenant C.V. Keyes, the Guides.

NATIVE RANKS.

Killed Wounded

11th Bengal Lancers.... 0 3

Horses........ 1 4

Guides Cavalry...... 1 10

Horses........ 3 18

Total casualties—16 men and 26 horses.

The vigorous resistance which the cavalry had encountered, and the great numbers and confidence that the enemy had displayed, effectually put an end to any idea of relieving Chakdara that day. The tribesmen were much elated by their temporary success, and the garrison, worn and wearied by the incessant strain, both mental and physical, were proportionately cast down. Every one anticipated tremendous fighting on the next day. Make the attempt, they must at all hazards. But there were not wanting those who spoke of “forlorn hopes” and “last chances.” Want of sleep and rest had told on all ranks. For a week they had grappled with a savage foe. They were the victors, but they were out of breath.

It was at this moment, that Sir Bindon Blood arrived and assumed the command. He found General Meiklejohn busily engaged in organising a force of all arms, which was to move to the relief of Chakdara on the following day. As it was dangerous to denude the Malakand position of troops, this force could not exceed 1000 rifles, the available cavalry and four guns. Of these arrangements Sir Bindon Blood approved. He relieved Brigadier-General Meiklejohn of the charge of the Malakand position, and gave him the command of the relieving column. Colonel Reid was then placed in command of Malakand, and instructed to strengthen the pickets at Castle Rock, as far as possible, and to be ready with a force taken from them, to clear the high ground on the right of the Graded road. The relieving column was composed as follows:—

400 Rifles 24th Punjaub Infantry.

400 " 45th Sikhs.

200 " Guides Infantry.

2 Squadrons 11th Bengal Lancers (under Lieut.-Col. R.B. Adams.)

2 " Guides Cavalry " " "

4 Guns No.8 Mountain Battery.

50 Sappers of No.5 Company.

Hospital details.

Sir Bindon Blood ordered General Meiklejohn to assemble this force before dark near the centre of the camp at a grove of trees called “Gretna Green,” to bivouac there for the night, and to be ready to start with the first light of morning. During the afternoon the enemy, encouraged by their success with the cavalry in the morning, advanced boldly to the pickets and the firing was continuous. So heavy indeed did it become between eleven and twelve o’clock at night, that the force at “Gretna Green” got under arms. But towards morning the tribesmen retired.

The reader may, perhaps, have in his mind the description of the Malakand as a great cup with jagged clefts in the rim. Much of this rim was still held by the enemy. It was necessary for any force trying to get out of the cup, to fight their way along the narrow roads through the clefts, which were commanded by the heights on either side. For a considerable distance it was impossible to deploy. Therein lay the difficulty of the operation, which the General had now to perform. The relieving column was exposed to the danger of being stopped, just as Colonel McRae had stopped the first attack of the tribesmen along the Buddhist road. On the 1st of August the cavalry had avoided these difficulties by going down the road to the North camp, and making a considerable detour. But they thus became involved in bad ground and had to retire. The “Graded” road, if any, was the road by which Chakdara was to be relieved. Looking at the tangled, rugged nature of the country, it seems extraordinary to an untrained eye, that among so many peaks and points, one should be of more importance than another. Yet it is so. On the high ground, in front of the position that Colonel McRae and the 45th Sikhs had held so well, was a prominent spur. This was the key which would unlock the gate and set free the troops, who were cramped up within. Every one realised afterwards how obvious this was and wondered they had not thought of it before. Sir Bindon Blood selected the point as the object of his first attack, and it was against this that he directed Colonel Goldney with a force of about 300 men to move, as soon as he should give the signal to advance.

At half-past four in the morning of the 2nd of August he proceeded to “Gretna Green” and found the relieving column fallen in, and ready to march at daybreak. All expected a severe action. Oppressed with fatigue and sleeplessness, there were many who doubted that it would be successful. But though tired, they were determined, and braced themselves for a desperate struggle. The General-in-chief was, as he had said, confident and serene. He summoned the different commanding officers, explained his plans, and shook hands all round. It was a moment of stern and high resolve. Slowly the first faint light of dawn grew in the eastern sky. The brightness of the stars began to pale. Behind the mountains was the promise of the sun. Then the word was given to advance. Immediately the relieving column set off, four deep, down the “Graded” road. Colonel Goldney simultaneously advanced to the attack of the spur, which now bears his name, with 250 men of the 35th Sikhs and 50 of the 38th Dogras. He moved silently towards the stone shelters, that the tribesmen had erected on the crest. He got to within a hundred yards unperceived. The enemy, surprised, opened an irregular and ineffective fire. The Sikhs shouted and dashed forward. The ridge was captured without loss of any kind. The enemy fled in disorder, leaving seven dead and one prisoner on the ground.

Then the full significance of the movement was apparent alike to friend and foe. The point now gained, commanded the whole of the “Graded” road, right down to its junction with the road to the North camp. The relieving column, moving down the road, were enabled to deploy without loss or delay. The door was open. The enemy, utterly surprised and dumfoundered by this manoeuvre, were seen running to and fro in the greatest confusion: in the graphic words of Sir Bindon Blood’s despatch, “like ants in a disturbed ant-hill.” At length they seemed to realise the situation, and, descending from the high ground, took up a position near Bedford Hill in General Meiklejohn’s front, and opened a heavy fire at close range. But the troops were now deployed and able to bring their numbers to bear. Without wasting time in firing, they advanced with the bayonet. The leading company of the Guides stormed the hill in their front with a loss of two killed and six wounded. The rest of the troops charged with even less loss. The enemy, thoroughly panic-stricken, began to fly, literally by thousands, along the heights to the right. They left seventy dead behind them. The troops, maddened by the remembrance of their fatigues and sufferings, and inspired by the impulse of victory, pursued them with a merciless vigour.

Sir Bindon Blood had with his staff ascended the Castle Rock, to superintend the operations generally. From this position the whole field was visible. On every side, and from every rock, the white figures of the enemy could be seen in full flight. The way was open. The passage was forced. Chakdara was saved. A great and brilliant success had been obtained. A thrill of exultation convulsed every one. In that moment the general, who watched the triumphant issue of his plans, must have experienced as fine an emotion as is given to man on earth. In that moment, we may imagine that the weary years of routine, the long ascent of the lower grades of the service, the frequent subordination to incompetence, the fatigues and dangers of five campaigns, received their compensation. Perhaps, such is the contrariness of circumstances, there was no time for the enjoyment of these reflections. The victory had been gained. It remained to profit by it. The enemy would be compelled to retire across the plain. There at last was the chance of the cavalry. The four squadrons were hurried to the scene.

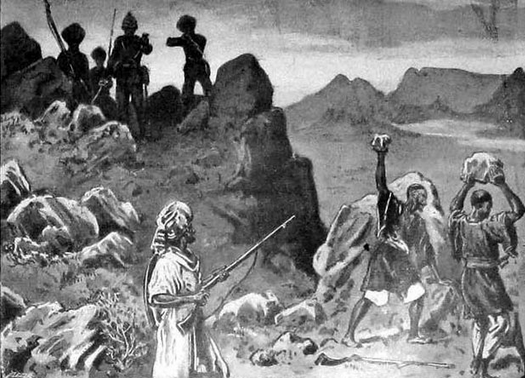

The 11th Bengal Lancers, forming line across the plain, began a merciless pursuit up the valley. The Guides pushed on to seize the Amandara Pass and relieve Chakdara. All among the rice fields and the rocks, the strong horsemen hunted the flying enemy. No quarter was asked or given, and every tribesman caught, was speared or cut down at once. Their bodies lay thickly strewn about the fields, spotting with black and green patches, the bright green of the rice crop. It was a terrible lesson, and one which the inhabitants of Swat and Bajaur will never forget. Since then their terror of Lancers has been extraordinary. A few sowars have frequently been sufficient to drive a hundred of these valiant savages in disorder to the hills, or prevent them descending into the plain for hours.

Meanwhile the infantry had been advancing swiftly. The 45th Sikhs stormed the fortified village of Batkhela near the Amandara Pass, which the enemy held desperately. Lieut.-Colonel McRae, who had been relieved from the command of the regiment by the arrival of Colonel Sawyer, was the first man to enter the village. Eighty of the enemy were bayoneted in Batkheka alone. It was a terrible reckoning.

I am anxious to finish with this scene of carnage. The spectator, who may gaze unmoved on the bloodshed of the battle, must avert his eyes from the horrors of the pursuit, unless, indeed, joining in it himself, he flings all scruples to the winds, and, carried away by the impetus of the moment, indulges to the full those deep-seated instincts of savagery, over which civilisation has but cast a veil of doubtful thickness.

The casualties in the relief of Chakdara were as follows:—

11th Bengal Lancers—killed and died from wounds, 3; wounded,3.

Killed. Wounded.

Guides Infantry....... 2 7

35th Sikhs......... 2 3

45th Sikhs......... 0 7

24th Punjaub Infantry..... 0 5

No.8 Bengal Mountain Battery... 0 1

Total Casualties—33

The news of the relief of Chakdara was received with feelings of profound thankfulness throughout India. And in England, in the House of Commons, when the Secretary of State read out the telegram, there were few among the members who did not join in the cheers. Nor need we pay much attention to those few.