Editor’s note: Here follows the sixteenth chapter of The Story of the Malakand Field Force: An Episode of Frontier War, by Winston S. Churchill (published 1898). All spelling in the original.

(Continued from Part 15)

CHAPTER XVI: SUBMISSION

"Their eyes were sunken and weary

With a sort of listless woe,

And they looked from their desolate eyrie

Over the plains below.

"Two had wounds from a sabre,

And one from an Enfield Ball."

"Rajpoot Rebels," LYALL.

At last the negotiations with the Mamunds began to reach a conclusion. The tribe were really desirous of peace, and prepared to make any sacrifices to induce the brigades to leave the valley. The Khan of Khar now proved of valuable assistance. He consistently urged them to make peace with the Sirkar, and assured them that the troops would not go away until they had their rifles back. Finally the Mamunds said they would get the rifles. But the path of repentance was a stony one. On the very night that the tribesmen decided for peace at any price, a thousand warlike Afghans, spoiling for a fight, arrived from the Kunar Valley, on the other side of the mountains, and announced their intention of attacking the camp at once. The Mamunds expostulated with them. The retainers of the Khan of Khar implored them not to be so rash. In the end these unwelcome allies were persuaded to depart. But that night the camp was warned that an attack was probable. The inlying pickets were accordingly doubled, and every man slept in his clothes, so as to be ready. The pathos of the situation was provided by the fact, that the Mamunds were guarding us from our enemies. The wretched tribe, rather than face a renewal of hostilities, had posted pickets all round the camp to drive away “snipers” and other assailants. Their sincerity was beyond suspicion.

The next day the first instalment of rifles was surrendered. Fifteen Martini-Henrys taken on the 16th from the 35th Sikhs were brought into camp, by the Khan of Khar’s men, and deposited in front of the general’s tent. Nearly all were hacked and marked by sword cuts, showing that their owners, the Sikhs, had perished fighting to the last. Perhaps, these firearms had cost more in blood and treasure than any others ever made. The remainder of the twenty-one were promised later, and have since all been surrendered. But the rifles as they lay on the ground were a bitter comment on the economic aspect of the “Forward Policy.” These tribes have nothing to surrender but their arms. To extort these few, had taken a month, had cost many lives, and thousands of pounds. It had been as bad a bargain as was ever made. People talk glibly of “the total disarmament of the frontier tribes” as being the obvious policy. No doubt such a result would be most desirable. But to obtain it would be as painful and as tedious an undertaking, as to extract the stings of a swarm of hornets, with naked fingers.

After the surrender of the rifles, the discussion of terms proceeded with smoothness. Full jirgahs were sent to the camp from the tribe, and gradually a definite understanding was reached. The tribesmen bewailed the losses they had sustained. Why, they asked, had the Sirkar visited them so heavily? Why, replied Major Deane, had they broken the peace and attacked the camp? The elders of the tribe, following the practice of all communities, threw the blame on their “young men.” These had done the evil, they declared. All had paid the penalty. At length definite terms were agreed to, and a full durbar was arranged for the 11th of the month for their ratification.

Accordingly on that date, at about one o’clock in the afternoon, a large and representative jirgah of Mamunds, accompanied by the Khans of Khar, Jar and Nawagai, arrived at the village of Nawa Kila, about half a mile from the camp. At three o’clock Sir Bindon Blood, with Major Deane, Chief Political Officer; Mr. Davis, Assistant Political Officer; most of the Headquarters staff, and a few other officers, started, escorted by a troop of the Guides Cavalry, for the durbar. The general on arrival shook hands with the friendly khans, much to their satisfaction, and took a seat which had been provided. The tribesmen formed three sides of a square. The friendly khans were on the left with their retainers. The Mamund jirgahs filled two other sides. Sir Bindon Blood, with Major Deane on his left and his officers around him, occupied the fourth side.

Then the Mamunds solemnly tendered their submission. They expressed their deep regret at their action, and deplored the disasters that had befallen them. They declared, they had only fought because they feared annexation. They agreed to expel the followers of Umra Khan from the valley. They gave security for the rifles that had not yet been surrendered. They were then informed that as they had suffered severe punishment and had submitted, the Sirkar would exact no fine or further penalty from them. At this they showed signs of gratification. The durbar, which had lasted fifteen minutes, was ended by the whole of the tribesmen swearing with uplifted hands to adhere to the terms and keep the peace. They were then dismissed.

The losses sustained by the Mamunds in the fighting were ascertained to be 350 killed, besides the wounded, with whom the hill villages were all crowded, and who probably amounted to 700 or 800. This estimate takes no account of the casualties among the transfrontier tribesmen, which were presumably considerable, but regarding which no reliable information could be obtained. Sir Bindon Blood offered them medical aid for their wounded, but this they declined. They could not understand the motive, and feared a stratagem. What the sufferings of these wretched men must have been, without antiseptics or anaesthetics, is terrible to think of. Perhaps, however, vigorous constitutions and the keen air of the mountains were Nature’s substitutes.

Thus the episode of the Mamund Valley came to an end. On the morning of the 12th, the troops moved out of the camp at Inayat Kila for the last time, and the long line of men, guns and transport animals, trailed slowly away across the plain of Khar. The tribesmen gathered on the hills to watch the departure of their enemies, but whatever feelings of satisfaction they may have felt at the spectacle, were dissipated when they turned their eyes towards their valley. Not a tower, not a fort was to be seen. The villages were destroyed. The crops had been trampled down. They had lost heavily in killed and wounded, and the winter was at hand. No defiant shots pursued the retiring column. The ferocious Mamunds were weary of war.

And as the soldiers marched away, their reflections could not have been wholly triumphant. For a month they had held Inayat Kila, and during that month they had been constantly fighting. The Mamunds were crushed. The Imperial power had been asserted, but the cost was heavy. Thirty-one officers and 251 men had been killed and wounded out of a fighting force that had on no occasion exceeded 1200 men.

The casualties of General Jeffrey’s brigade in the Mamund Valley were as follows:—

British Officers.... Killed or died of wounds 7

" " .... Wounded.... 17

" Soldiers.... Killed .... 7

" " .... Wounded.... 41

Native Officers .... Killed .... 0

" " .... Wounded.... 7

" Soldiers .... Killed .... 48

" " .... Wounded.... 147

Followers ...... ..... 8

——

Total..... 282

Horses and mules..... ..... 150

The main cause of this long list of casualties was, as I have already written, the proximity of the Afghan border. But it would be unjust and ungenerous to deny to the people of the Mamund Valley that reputation for courage, tactical skill and marksmanship, which they have so well deserved. During an indefinite period they had brawled and fought in the unpenetrated gloom of barbarism. At length they struck a blow at civilisation, and civilisation, though compelled to record the odious vices that the fierce light of scientific war exposed, will yet ungrudgingly admit that they are a brave and warlike race. Their name will live in the minds of men for some years, even in this busy century, and there are families in England who will never forget it. But perhaps the tribesmen, sitting sullenly on the hillsides and contemplating the ruin of their habitations, did not realise all this, or if they did, still felt regret at having tried conclusions with the British Raj. Their fame had cost them dear. Indeed, as we have been told, “nothing is so expensive as glory.”

The troops camped on the night of the 12th at Jar, and on the following day moved up the Salarzai Valley to Matashah. Here they remained for nearly a week. This tribe, terrified by the punishment of the Mamunds, made no regular opposition, though the camp was fired into regularly every night by a few hot-blooded “snipers.” Several horses and mules were hit, and a sowar in the Guides Cavalry was wounded. The reconnaissances in force, which were sent out daily to the farther end of the valley, were not resisted in any way, and the tribal jirgahs used every effort to collect the rifles which they had been ordered to surrender. By the 19th all were given up, and on the 20th the troops moved back to Jar. There Sir Bindon Blood received the submission of the Utman Khels, who brought in the weapons demanded from them, and paid a fine as an indemnity for attacking the Malakand and Chakdara.

The soldiers, who were still in a fighting mood, watched with impatience the political negotiations which produced so peaceful a triumph.

All Indian military commanders, from Lord Clive and Lord Clive’s times downwards, have inveighed against the practice of attaching civil officers to field forces. It has been said, frequently with truth, that they hamper the military operations, and by interfering with the generals, infuse a spirit of vacillation into the plans. Although the political officers of the Malakand Field Force were always personally popular with their military comrades, there were many who criticised their official actions, and disapproved of their presence. The duties of the civil officers, in a campaign, are twofold: firstly, to negotiate, and secondly, to collect information. It would seem that for the first of these duties they are indispensable. The difficult language and peculiar characters of the tribesmen are the study of a lifetime. A knowledge of the local conditions, of the power and influence of the khans, or other rulers of the people; of the general history and traditions of the country, is a task which must be entirely specialised. Rough and ready methods are excellent while the tribes resist, but something more is required when they are anxious to submit. Men are needed who understand the whole question, and all the details of the quarrel, between the natives and the Government, and who can in some measure appreciate both points of view. I do not believe that such are to be found in the army. The military profession is alone sufficient to engross the attention of the most able and accomplished man.

Besides this I cannot forget how many quiet nights the 2nd Brigade enjoyed at Inayat Kila when the “snipers” were driven away by the friendly pickets; how many fresh eggs and water melons were procured, and how easily letters and messages were carried about the country [As correspondent of the Pioneer, I invariably availed myself of this method of sending the press telegrams to the telegraph office at Panjkora, and though the route lay through twenty miles of the enemy’s country, these messages not only never miscarried, but on several occasions arrived before the official despatches or any heliographed news. By similar agency the bodies of Lieutenant-Colonel O’Bryen and Lieutenant Browne-Clayton, killed in the attack upon Agrah on the 30th of September, were safely and swiftly conveyed to Malakand for burial.] through the relations which the political officers, Mr. Davis and Mr. Gunter, maintained, under very difficult circumstances, with these tribesmen, who were not actually fighting us.

Respecting the second duty, it is difficult to believe that the collection of information as to the numbers and intentions of the enemy would not be better and more appropriately carried out by the Intelligence Department and the cavalry. Civil officers should not be expected to understand what kind of military information a general requires. It is not their business. I am aware that Mr. Davis procured the most correct intelligence about the great night attack at Nawagai, and thus gave ample warning to Sir Bindon Blood. But on the other hand the scanty information available about the Mamunds, previous to the action of the 16th, was the main cause of the severe loss sustained on that day. Besides, the incessant rumours of a night attack on Inayat Kila, kept the whole force in their boots about three nights each week. Civil officers should discharge diplomatic duties, and military officers the conduct of war. And the collection of information is one of the most important of military duties. Our Pathan Sepoys, the Intelligence Branch, and an enterprising cavalry, should obtain all the facts that a general requires to use in his plans. At least the responsibility can thus be definitely assigned.

On one point, however, I have no doubts. The political officers must be under the control of the General directing the operations. There must be no “Imperium in imperio.” In a Field Force one man only can command—and all in it must be under his authority. Differences, creating difficulties and leading to disasters, will arise whenever the political officers are empowered to make arrangements with the tribesmen, without consulting and sometimes without even informing the man on whose decisions the success of the war and the lives of the soldiers directly depend.

The subject is a difficult one to discuss, without wounding the feelings of those gallant men, who take all the risks of war, while the campaign lasts, and, when it is over, live in equal peril of their lives among the savage populations, whose dispositions they study, and whose tempers they watch. I am glad to have done with it.

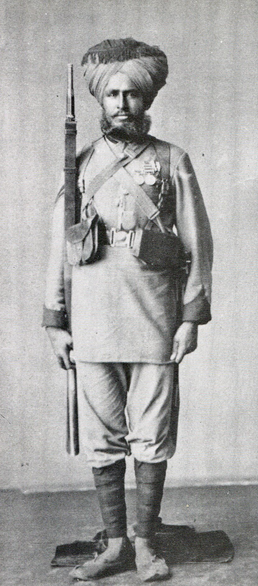

During the stay of the brigades in Bajaur, there had been several cases of desertion among the Afridi Sepoys. On one occasion five men of the 24th Punjaub Infantry, who were out on picket, departed in a body, and taking their arms with them set off towards Tirah and the Khyber Pass. As I have recorded several instances of gallantry and conduct among the Afridis and Pathans in our ranks, it is only fitting that the reverse of the medal should be shown. The reader, who may be interested in the characters of the subject races of the Empire, and of the native soldiers, on whom so much depends, will perhaps pardon a somewhat long digression on the subject of Pathans and Sikhs.

It should not be forgotten by those who make wholesale assertions of treachery and untrustworthiness against the Afridi and Pathan soldiers, that these men are placed in a very strange and false position. They are asked to fight against their countrymen and co-religionists. On the one side are accumulated all the forces of fanaticism, patriotism and natural ties. On the other military associations stand alone. It is no doubt a grievous thing to be false to an oath of allegiance, but there are other obligations not less sacred. To respect an oath is a duty which the individual owes to society. Yet, who would by his evidence send a brother to the gallows? The ties of nature are older and take precedence of all other human laws. When the Pathan is invited to suppress his fellow-countrymen, or even to remain a spectator of their suppression, he finds himself in a situation at which, in the words of Burke, “Morality is perplexed, reason staggered, and from which affrighted nature recoils.”

There are many on the frontier who realise these things, and who sympathise with the Afridi soldier in his dilemma. An officer of the Guides Infantry, of long experience and considerable distinction, who commands both Sikhs and Afridis, and has led both many times in action, writes as follows: “Personally, I don’t blame any Afridis who desert to go and defend their own country, now that we have invaded it, and I think it is only natural and proper that they should want to do so.”

Such an opinion may be taken as typical of the views of a great number of officers, who have some title to speak on the subject, as it is one on which their lives might at any moment depend.

The Sikh is the guardian of the Marches. He was originally invented to combat the Pathan. His religion was designed to be diametrically opposed to Mahommedanism. It was a shrewd act of policy. Fanaticism was met by fanaticism. Religious abhorrence was added to racial hatred. The Pathan invaders were rolled back to the mountains, and the Sikhs established themselves at Lahore and Peshawar. The strong contrast, and much of the animosity, remain to-day. The Sikh wears his hair down to his waist; the Pathan shaves his head. The Sikh drinks what he will; the Pathan is an abstainer. The Sikh is burnt after death; the Pathan would be thus deprived of Paradise. As a soldier the Pathan is a finer shot, a hardier man, a better marcher, especially on the hillside, and possibly an even more brilliant fighter. He relies more on instinct than education: war is in his blood; he is a born marksman, but he is dirty, lazy and a spendthrift.

In the Sikh the more civilised man appears. He does not shoot naturally, but he learns by patient practice. He is not so tough as the Pathan, but he delights in feats of strength—wrestling, running, or swimming. He is a much cleaner soldier and more careful. He is frequently parsimonious, and always thrifty, and does not generally feed himself as well as the Pathan. [Indeed in some regiments the pay of very thin Sikhs is given them in the form of food, and they have to be carefully watched by their officers till they get fat and strong.]

There are some who say that the Sikh will go on under circumstances which will dishearten and discourage his rival, and that if the latter has more dash he has less stamina. The assertion is not supported by facts. In 1895, when Lieut.-Colonel Battye was killed near the Panjkora River and the Guides were hard pressed, the subadar of the Afridi company, turning to his countrymen, shouted: “Now, then, Afridi folk of the Corps of Guides, the Commanding Officer’s killed, now’s the time to charge!” and the British officers had the greatest difficulty in restraining these impetuous soldiers from leaving their position, and rushing to certain death. The story recalls the speech of the famous cavalry colonel at the action of Tamai, when the squares were seen to be broken, and an excited and demoralised correspondent galloped wildly up to the squadrons, declaring that all was lost. “How do you mean, ‘all’s lost’? Don’t you see the 10th Hussars are here?” There are men in the world who derive as stern an exultation from the proximity of disaster and ruin as others from success, and who are more magnificent in defeat than others are in victory. Such spirits are undoubtedly to be found among the Afridis and Pathans.

I will quote, in concluding this discussion, the opinion of an old Gurkha subadar who had seen much fighting. He said that he liked the Sikhs better, but would sooner have Afridis with him at a pinch than any other breed of men in India. It is comfortable to reflect, that both are among the soldiers of the Queen.

Although there were no Gurkhas in the Malakand Field Force, it is impossible to consider Indian fighting races without alluding to these wicked little men. In appearance they resemble a bronze Japanese. Small, active and fierce, ever with a cheery grin on their broad faces, they combine the dash of the Pathan with the discipline of the Sikh. They spend all their money on food, and, unhampered by religion, drink, smoke and swear like the British soldier, in whose eyes they find more favour than any other—as he regards them—breed of “niggers.” They are pure mercenaries, and, while they welcome the dangers, they dislike the prolongation of a campaign, being equally eager to get back to their wives and to the big meat meals of peace time.

After the Utman Khels had been induced to comply with the terms, the brigades recrossed the Panjkora River, and then marching by easy stages down the line of communications, returned to the Malakand. The Guides, moving back to Mardan, went into cantonments again, and turned in a moment from war to peace. The Buffs, bitterly disappointed at having lost their chance of joining in the Tirah expedition, remained at Malakand in garrison. A considerable force was retained near Jalala, to await the issue of the operations against the Afridis, and to be ready to move against the Bunerwals, should an expedition be necessary.

Here we leave the Malakand Field Force. It may be that there is yet another chapter of its history which remains to be written, and that the fine regiments of which it is composed will, under their trusted commander, have other opportunities of playing the great game of war. If that be so, the reader shall decide whether the account shall prolong the tale I have told, or whether the task shall fall to another hand. [It is an excellent instance of the capricious and haphazard manner in which honours and rewards are bestowed in the army, that the operations in the Mamund Valley and throughout Bajaur are commemorated by no distinctive clasp. The losses sustained by the Brigade were indisputably most severe. The result was successful. The conduct of the troops has been officially commended. Yet the soldiers who were engaged in all the rough fighting I have described in the last eight chapters have been excluded from any of the special clasps which have been struck. They share the general clasp with every man who crossed the frontier and with some thousands who never saw a shot fired.]