Editor’s note: Here follows the twelfth chapter of The Story of the Malakand Field Force: An Episode of Frontier War, by Winston S. Churchill (published 1898). All spelling in the original.

CHAPTER XII: AT INAYAT KILA

"Two thousand pounds of education

Drops to a ten-rupee jezail.

. . . . . .

Strike hard who cares. Shoot straight who can.

The odds are on the cheaper man."

RUDYARD KIPLING.

Half an hour before dawn on the 17th, the cavalry were mounted, and as soon as the light was strong enough to find a way through the broken ground, the squadron started in search of the missing troops. We had heard no more of their guns since about two o’clock. We therefore concluded they had beaten off the enemy. There might, of course, be another reason for their silence. As we drew near Bilot, it was possible to distinguish the figures of men moving about the walls and houses. The advanced files rode cautiously forward. Suddenly they cantered up to the wall and we knew some at least were alive. Captain Cole, turning to his squadron, lifted his hand. The sowars, actuated by a common impulse, rose in their stirrups and began to cheer. But there was no response. Nor was this strange. The village was a shambles. In an angle of the outside wall, protected on the third side by a shallow trench, were the survivors of the fight. All around lay the corpses of men and mules. The bodies of five or six native soldiers were being buried in a hurriedly dug grave. It was thought that, as they were Mahommedans, their resting-place would be respected by the tribesmen. [These bodies were afterwards dug up and mutilated by the natives: a foul act which excited the fury and indignation of soldiers of every creed in the force. I draw the reader’s attention to this unpleasant subject, only to justify what I have said in an earlier chapter of the degradation of mind in which the savages of the mountains are sunk.] Eighteen wounded men lay side by side in a roofless hut. Their faces, drawn by pain and anxiety, looked ghastly in the pale light of the early morning. Two officers, one with his left hand smashed, the other shot through both legs, were patiently waiting for the moment when the improvised tourniquets could be removed and some relief afforded to their sufferings. The brigadier, his khaki coat stained with the blood from a wound on his head, was talking to his only staff-officer, whose helmet displayed a bullet-hole. The most ardent lover of realism would have been satisfied. Food, doolies, and doctors soon arrived. The wounded were brought to the field hospitals to be attended to. The unwounded hurried back to camp to get breakfast and a bath. In half an hour, the ill-omened spot was occupied only by the few sowars engaged in shooting the wounded mules, and by the vultures who watched the proceedings with an expectant interest.

Gradually we learnt the story of the night. The battery, about thirty sappers and half the 35th Sikhs, were returning to camp. At about seven o’clock an order was sent for them to halt and remain out all night, to assist the Guides Infantry, whose firing could be heard and for whose safety the brigadier was above all things anxious. This order reached the battery, and with the sappers as an escort they turned back, recrossed a nullah and met the general with two companies of Sikhs outside the village of Bilot. The half-battalion of the 35th did not apparently receive the order, for they continued their march. Lieutenant Wynter, R.A., was sent back to look for them. He did not find them, but fell in with four fresh companies, two of the Guides and two of the 35th, who, under Major Worlledge, had been sent from camp in response to the general’s demand for reinforcements. Lieutenant Wynter brought these back, as an escort to the guns. On arrival at the village, the brigadier at once sent them to the assistance of the Guides. He counted on his own two companies of Sikhs. But when Worlledge had moved off and had already vanished in the night, it was found that these two companies had disappeared. They had lost touch in the darkness, and, not perceiving that the general had halted, had gone on towards camp. Thus the battery was left with no other escort than thirty sappers.

A party of twelve men of the Buffs now arrived, and the circumstances which led them to the guns are worth recording. When the Buffs were retiring through the villages, they held a Mahommedan cemetery for a little while, in order to check the enemy’s advance. Whilst there, Lieutenant Byron, Orderly Officer to General Jeffreys, rode up and told Major Moody, who commanded the rear companies, that a wounded officer was lying in a dooly a hundred yards up the road, without any escort. He asked for a few men. Moody issued an order, and a dozen soldiers under a corporal started to look for the dooly. They missed it, but while searching, found the general and the battery outside the village. The presence of these twelve brave men—for they fully maintained the honour of their regiment—with their magazine rifles, just turned the scale. Had not the luck of the British army led them to the village, it can hardly be doubted, and certainly was not doubted by any who were there, that the guns would have been captured and the general killed. Fortune, especially in war, uses tiny fulcra for her powerful lever.

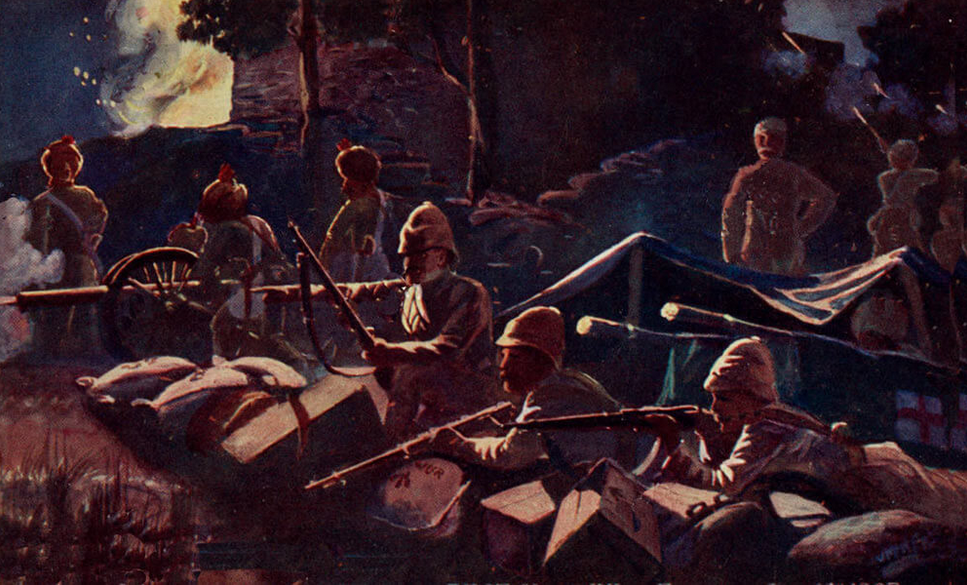

The general now ordered the battery and sappers to go into the village, but it was so full of burning bhoosa, that this was found to be impossible, and they set to work to entrench themselves outside. The village was soon full of the enemy. From the walls and houses, which on two sides commanded the space occupied by the battery, they began to fire at about thirty yards’ range. The troops were as much exposed as if they had been in a racket court, of which the enemy held the walls. They could not move, because they would have had to desert either the guns or the wounded. Fortunately, not many of the tribesmen at this point were armed with rifles. The others threw stones and burning bhoosa into the midst of the little garrison. By its light they took good aim. Everybody got under such cover as was available. There was not much. Gunner Nihala, a gallant native soldier, repeatedly extinguished the burning bhoosa with his cloak at the imminent peril of his life. Lieutenants Watson and Colvin, with their sappers and the twelve men of the Buffs, forced their way into the village, and tried to expel the enemy with the bayonet. The village was too large for so small a party to clear. The tribesmen moved from one part to another, repeatedly firing. They killed and wounded several of the soldiers, and a bullet smashed Lieutenant Watson’s hand. He however continued his efforts and did not cease until again shot, this time so severely as to be unable to stand. His men carried him from the village, and it was felt that it would be useless to try again.

The attention of the reader is directed to the bravery of this officer. After a long day of marching, and fighting, in the dark, without food and with small numbers, the man who will go on, unshaken and unflinching, after he has received a severe and painful wound, has in respect of personal courage few equals and no superior in the world. It is perhaps as high a form of valour to endure as to dare. The combination of both is sublime. [Both officers have received the Victoria Cross for their conduct on this occasion.]

At nine o’clock the rain stopped the firing, as the tribesmen were afraid of wetting their powder, but at about ten they opened again. They now made a great hole in the wall of the village, through which about a dozen men fired with terrible effect. Others began loopholing the walls. The guns fired case shot at twenty yards’ range at these fierce pioneers, smashing the walls to pieces and killing many. The enemy replied with bullets, burning bhoosa and showers of stones.

So the hours dragged away. The general and Captain Birch were both wounded, early in the night. Lieutenant Wynter, while behaving with distinguished gallantry, was shot through both legs at about 11.30. He was thus twice severely wounded within forty-five days. He now continued to command his guns, until he fainted from loss of blood. A native gunner then shielded him with his body, until he also was hit. The whole scene, the close, desperate fighting, the carcasses of the mules, the officers and men crouching behind them, the flaming stacks of bhoosa, the flashes of the rifles, and over all and around all, the darkness of the night—is worthy of the pencil of De Neuville.

At length, at about midnight, help arrived. Worlledge’s two companies had gone in search of the Guides, but had not found them. They now returned and, hearing the firing at Bilot, sent an orderly of the 11th Bengal Lancers to ask if the general wanted assistance. This plucky boy—he was only a young recruit—rode coolly up to the village although the enemy were all around, and he stood an almost equal chance of being shot by our own men. He soon brought the two companies to the rescue, and the enemy, balked of their prey, presently drew off in the gloom. How much longer the battery and its defenders could have held out is uncertain. They were losing men steadily, and their numbers were so small that they might have been rushed at any moment. Such was the tale.

No operations took place on the 17th. The soldiers rested, casualties were counted, wounds were dressed, confidence was restored. The funerals of the British officers and men, killed the day before, took place at noon. Every one who could, attended; but all the pomp of military obsequies was omitted, and there were no Union Jacks to cover the bodies, nor were volleys fired over the graves, lest the wounded should be disturbed. Somewhere in the camp—exactly where, is now purposely forgotten—the remains of those who had lost, in fighting for their country, all that men can be sure of, were silently interred. No monument marked the spot. The only assurance that it should be undisturbed is, that it remains unknown. Nevertheless, the funerals were impressive. To some the game of war brings prizes, honour, advancement, or experience; to some the consciousness of duty well discharged; and to others—spectators, perhaps—the pleasure of the play and the knowledge of men and things. But here were those who had drawn the evil numbers—who had lost their all, to gain only a soldier’s grave. Looking at these shapeless forms, coffined in a regulation blanket, the pride of race, the pomp of empire, the glory of war appeared but the faint and unsubstantial fabric of a dream; and I could not help realising with Burke: “What shadows we are and what shadows we pursue.”

The actual casualties were, in proportion to the numbers engaged, greater than in any action of the British army in India for many years. Out of a force which at no time exceeded 1000 men, nine British officers, four native officers, and 136 soldiers were either killed or wounded. The following is the full return:—

BRITISH OFFICERS.

Killed—Lieutenant and Adjutant V. Hughes, 35th Sikhs.

" " A.T. Crawford, R.A.

Wounded severely—Captain W.I. Ryder, attd. 35th Sikhs.

" " Lieutenant O.G. Gunning, 35th Sikhs.

" " " O.R. Cassells, 35th Sikhs.

" " " T.C. Watson, R.E.

" " " F.A. Wynter, R.A.

Wounded slightly—Brigadier-General Jeffreys, Commanding 2nd Bde.

M.F.F.

" " Captain Birch, R.A.

BRITISH SOLDIERS.

Killed. Wounded.

The Buffs . . . . 2 9

NATIVE RANKS.

Killed. Wounded.

11th Bengal Lancers . . 0 2

No.8 Mountain Battery. . 6 21

Guides Infantry. . . 2 10

35th Sikhs. . . . 22 45

38th Dogras. . . . 0 2

Sappers.. . . . 4 15

Total Casualties, 149; with 48 horses and mules.

The action of the 16th September is considered by some to have been a reverse. I do not think this view is justified by the facts. The troops accomplished every task they were set. They burned the village of Shahi-Tangi most completely, in spite of all opposition, and they inflicted on the tribesmen a loss of over 200 men. The enemy, though elated by the capture of twenty-two rifles from the bodies of the killed, were impressed by the bravery of the troops. “If,” they are reported to have said, “they fight like this when they are divided, we can do nothing.” Our losses were undoubtedly heavy and out of all proportion to the advantages gained. They were due to an ignorance, shared by all in the force, of the numbers and fighting power of the Mamunds. No one knew, though there were many who were wise after the event, that these tribesmen were as well armed as the troops, or that they were the brave and formidable adversaries they proved themselves. “Never despise your enemy” is an old lesson, but it has to be learnt afresh, year after year, by every nation that is warlike and brave. Our losses were also due to the isolation of Captain Ryder’s company, to extricate which the whole force had to wait till overtaken by darkness. It has been said that war cannot be made without running risks, nor can operations be carried out in the face of an enemy armed with breech-loaders without loss. No tactics can altogether shield men from bullets. Those serene critics who note the errors, and forget the difficulties, who judge in safety of what was done in danger, and from the security of peace, pronounce upon the conduct of war, should remember that the spectacle of a General, wounded, his horse shot, remaining on the field with the last unit, anxious only for the safety of his soldiers, is a spectacle not unworthy of the pages of our military history.

The depression, caused by the loss of amiable and gallant comrades, was dispelled by the prospects of immediate action. Sir Bindon Blood, whose position at Nawagai was now one of danger, sent the brigadier, instead of reinforcements, orders to vigorously prosecute the operations against the tribesmen, and on the morning of the 18th the force moved to attack the village of Domodoloh, which the 38th Dogras had found so strongly occupied on the 16th. Again the enemy were numerous. Again they adopted their effective tactics; but this time no chances were given them. The whole brigade marched concentrated to the attack, and formed up on the level ground just out of shot. The general and his staff rode forward and reconnoitered.

The village lay in a re-entrant of the hills, from which two long spurs projected like the piers of a harbour. Behind, the mountains rose abruptly to a height of 5000 feet. The ground, embraced by the spurs, was filled with crops of maize and barley. A fort and watch-tower guarded the entrance. At 8.30 the advance was ordered. The enemy did not attempt to hold the fort, and it was promptly seized and blown up. The explosion was a strange, though, during the fighting in the Mamund Valley, not an uncommon sight. A great cloud of thick brown-red dust sprang suddenly into the air, bulging out in all directions. The tower broke in half and toppled over. A series of muffled bangs followed. The dust-cloud cleared away, and nothing but a few ruins remained.

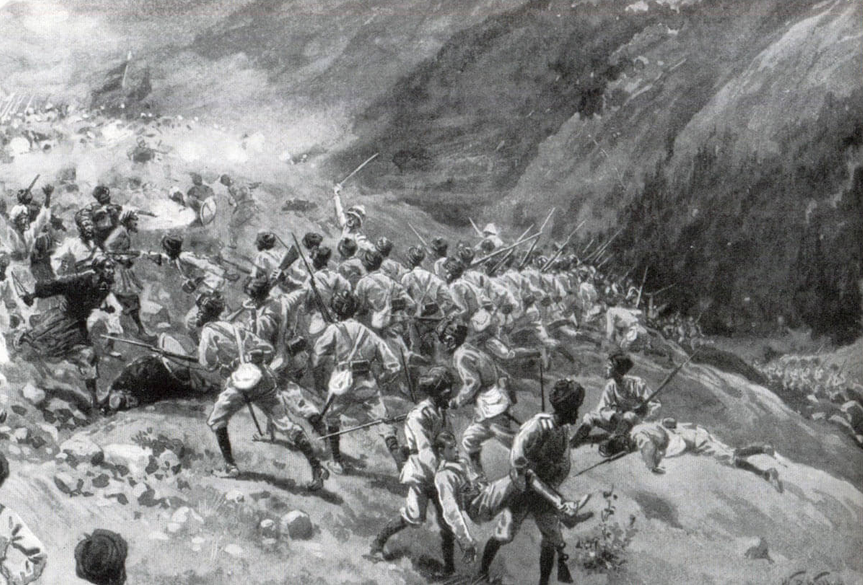

The enemy now opened fire from the spurs, both of which became crowned with little circles of white smoke. The 35th Sikhs advancing cleared the right ridge: the 38th Dogras the left. The Guides moved on the village, and up the main re-entrant itself. The Buffs were in reserve. The battery came into action on the left, and began shelling the crests of the opposite hills. Taking the range with their instruments, they fired two shots in rapid succession, each time at slightly different ranges. The little guns exploded with a loud report. Then, far up the mountain side, two balls of smoke appeared, one above the other, and after a few seconds the noise of the bursting shells came faintly back. Usually one would be a little short of—and the other a little over—the point aimed at. The next shot, by dividing the error, would go home, and the dust of the splinters and bullets would show on the peak, from which the tribesmen were firing, and it would become silent and deserted—the scene of an unregarded tragedy. Gradually the spurs were cleared of the enemy and the Guides, passing through the village, climbed up the face of the mountain and established themselves among the great rocks of the steep water-course. Isolated sharpshooters maintained a dropping fire. The company whose operations I watched,—Lieutenant Lockhart’s,—killed one of these with a volley, and we found him sitting by a little pool, propped against a stone. He had been an ugly man originally, but now that the bones of his jaw and face were broken in pieces by the bullet, he was hideous to look upon. His only garment was a ragged blue linen cloak fastened at the waist. There he sat—a typical tribesman, ignorant, degraded, and squalid, yet brave and warlike; his only property, his weapon, and that his countrymen had carried off. I could not help contrasting his intrinsic value as a social organism, with that of the officers who had been killed during the week, and those lines of Kipling which appear at the beginning of this chapter were recalled to mind with a strange significance. Indeed I often heard them quoted in the Watelai Valley.

The sappers had now entered the village, and were engaged in preparing the hovels of which it consisted for destruction. Their flat roofs are covered with earth, and will not burn properly, unless a hole is made first in each. This took time. Meanwhile the troops held on to the positions they had seized, and maintained a desultory fire with the enemy. At about noon the place was lighted up, and a dense cloud of smoke rose in a high column into the still air. Then the withdrawal of the troops was ordered. Immediately the enemy began their counter attack. But the Guides were handled with much skill. The retirement of each company was covered by the fire of others, judiciously posted farther down the hill. No opportunity was offered to the enemy. By one o’clock all the troops were clear of the broken ground. The Buffs assumed the duty of rear-guard, and were delighted to have a brisk little skirmish—fortunately unattended with loss of life—with the tribesmen, who soon reoccupied the burning village. This continued for, perhaps, half an hour, and meanwhile the rest of the brigade returned to camp.

The casualties in this highly successful affair were small. It was the first of six such enterprises, by which Brigadier-General Jeffreys, with stubborn perseverance, broke the spirit of the Mamund tribesmen.

Killed. Wounded.

35th Sikhs....... 2 3

Guides Infantry...... 0 1

38th Dogras....... 0 2

Total casualties, 8.

The enemy’s losses were considerable, but no reliable details could be obtained.

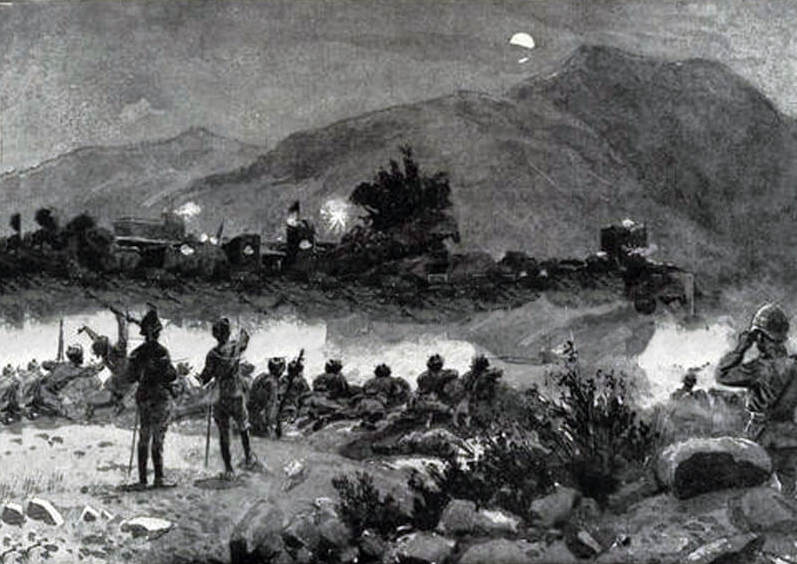

On the 19th the troops rested, and only foraging parties left the camp. On the 20th, fighting was renewed. From the position at the entrance to the valley it was possible to see all the villages that lay in the hollows of the hills, and to distinguish not only the scenes of past but also of future actions. The particular village which was selected for chastisement was never mentioned by name, and it was not until the brigade had marched some miles from the camp, that the objective became evident. The tribesmen therefore continued in a state of “glorious uncertainty,” and were unable to gather in really large numbers. At 5.30 A.M. the brigade started, and, preceded by the cavalry, marched up the valley—a long brown stream of men. Arrived nearly at the centre, the troops closed up into a more compact formation. Then suddenly the head wheeled to the left, and began marching on the village of Zagai. Immediately from high up on the face of the mountain a long column of smoke shot into the air. It was a signal fire. Other hills answered it. The affair now became a question of time. If the village could be captured and destroyed before the clans had time to gather, then there would be little fighting. But if the force were delayed or became involved, it was impossible to say on what scale the action would be.

The village of Zagai stands in a similar situation to that of Domodoloh. On either side long spurs advance into the valley, and the houses are built in terraces on the sides of the hollow so formed. Great chenar trees, growing in all their luxuriant beauty out of the rocky ground by the water-course, mark the hillside with a patch of green in contrast to the background of sombre brown. As the troops approached in fine array, the sound of incessant drumming was faintly heard, varied from time to time by the notes of a bugle. The cavalry reconnoitered and trotted off to watch the flank, after reporting the place strongly occupied. The enemy displayed standards on the crests of the spurs. The advance continued: the Guides on the left, the 38th Dogras in the centre, the Buffs on the right, and the 35th Sikhs in reserve. Firing began on the left at about nine o’clock, and a quarter of an hour later the guns came into action near the centre. The Guides and Buffs now climbed the ridges to the right and left. The enemy fell back according to their custom, “sniping.” Then the 38th pushed forward and occupied the village, which was handed over to the sappers to destroy. This they did most thoroughly, and at eleven o’clock a dense white smoke was rising from the houses and the stacks of bhoosa. Then the troops were ordered to withdraw. “Facilis ascensus Averni sed…;” without allowing the quotation to lead me into difficulties, I will explain that while it is usually easy to advance against an Asiatic, all retirements are matters of danger. While the village was being destroyed the enemy had been collecting. Their figures could be distinguished on the top of the mountain—a numerous line of dark dots against the sky; others had tried to come, from the adjoining valleys on the left and right. Those on the right succeeded, and the Buffs were soon sharply engaged. On the left the cavalry again demonstrated the power of their arm. A large force of tribesmen, numbering at least 600 men, endeavoured to reach the scene of action. To get there, however, they had to cross the open ground, and this, in face of the Lancers, they would not do. Many of these same tribesmen had joined in the attack on the Malakand, and had been chased all across the plain of Khar by the fierce Indian horsemen. They were not ambitious to repeat the experience. Every time they tried to cross the space, which separated them from their friends, Captain Cole trotted forward with his squadron, which was only about fifty strong, and the tribesmen immediately scurried back to the hills. For a long time they were delayed, and contented themselves by howling out to the sowars, that they would soon “make mincemeat of them,” to which the latter replied that they were welcome to try. At length, realising that they could not escape the cavalry, if they left the hills, they made a long circuit and arrived about half an hour after the village was destroyed and the troops had departed.

Nevertheless, as soon as the retirement was seen to be in progress, a general attack was made all along the line. On the left, the Guides were threatened by a force of about 500 men, who advanced displaying standards, and waving swords. They dispersed these and drove them away by a steady long-range fire, killing and wounding a large number. On the right, the Buffs were harassed by being commanded by another spur. Lieutenant Hasler’s company, which I accompanied, was protected from this flanking fire by the ground. A great many bullets, however, hummed overhead, and being anxious to see whence these were coming, the lieutenant walked across the crest to the far side. The half-company here was briskly engaged. From a point high up the mountain an accurate fire was directed upon them. We tried to get the range of this point with the Lee-Metford rifles. It was, as nearly as could be determined, 1400 yards. The tribesmen were only armed with Martini-Henrys. They nevertheless made excellent practice. Lieutenant R.E. Power was shot through the arm and, almost immediately afterwards, Lieutenant Keene was severely wounded in the body. Luckily, the bullet struck his sword-hilt first or he would have been killed. Two or three men were also wounded here. Those who know the range and power of the Martini-Henry rifle will appreciate the skill and marksmanship which can inflict loss even at so great a range.

As the retirement proceeded, the tribesmen came to closer quarters. The Buffs, however, used their formidable weapon with great effect. I witnessed one striking demonstration of its power. Lieutenant F.S. Reeves remained behind with a dozen men to cover the withdrawal of his company, and in hopes of bringing effective fire to bear on the enemy, who at this time were pressing forward boldly. Three hundred yards away was a nullah, and along this they began running, in hopes of cutting off the small party. At one point, however, the line of their advance was commanded by our fire. Presently a man ran into the open. The section fired immediately. The great advantage of the rifle was that there was no difficulty about guessing the exact range, as the fixed sight could be used. The man dropped—a spot of white. Four others rushed forward. Again there was a volley. All four fell and remained motionless. After this we made good our retreat almost unmolested.

As soon as the troops were clear of the hills, the enemy occupied the rocks and ridges, and fired at the retreating soldiers. The Buffs’ line of retirement lay over smooth, open ground. For ten minutes the fire was hot. Another officer and seven or eight men dropped. The ground was wet and deep, and the bullets cutting into the soft mud, made strange and curious noises. As soon as the troops got out of range, the firing ceased, as the tribesmen did not dare follow into the open.

On the extreme left, considerable bodies of the enemy appeared, and for a moment it seemed that they would leave the hills and come into the plain. The cavalry, however, trotted forward, and they ran back in confusion, bunching together as they did so. The battery immediately exploded two shrapnel shells in their midst with great effect. This ended the affair, and the troops returned to camp. The casualties were as follows:—

BRITISH OFFICERS.

Wounded severely—2nd Lieutenant G.N.S. Keene.

" slightly—Captain L.I.B. Hulke.

" " —Lieutenant R.E. Power.

BRITISH SOLDIERS.

Killed. Wounded.

Buffs. . . . . 1 10

(Died of wounds).

Native Ranks.

Wounded.

38th Dogras . . .. 2

Total casualties, 16.

I shall make the reader no apology for having described at such length, what was after all only a skirmish. The picture of the war on the frontier is essentially one of detail, and it is by the study of the details alone that a true impression can be obtained.

On the 22nd and 23rd the villages of Dag and Tangi were respectively captured and destroyed, but as the resistance was slight and the operations were unmarked by any new features, I shall not weary the reader by further description. The casualties were:—

BRITISH OFFICER.

Wounded—Major S. Moody, the Buffs.

NATIVE RANKS.

Killed. Wounded.

Guides Infantry. . . 1 2

38th Dogras. . . . 0 2

By these operations the tribesmen of the Mamund Valley had been severely punished. Any exultation which they might have felt over the action of the 16th was completely effaced. The brigade had demonstrated its power to take and burn any village that might be selected, and had inflicted severe loss on all who attempted to impede its action. The tribesmen were now thoroughly disheartened, and on the 21st began to sue for peace.

The situation was, however, complicated by the proximity of the Afghan frontier. The western side of the Mamund Valley is bounded by the mountains of the Hindu Raj range, along the summits of which is the Durand line of demarcation with the Amir. On the farther side of this range Gholam Hyder, the Afghan commander-in-chief, lay with a powerful force, which, at the time of the actions I have described, amounted to nine battalions, six squadrons and fourteen mountain guns. During the attack upon Zagai, numerous figures in khaki uniform had been observed on the higher slopes of the hills, and it was alleged that one particular group appeared to be directing the movements of the tribesmen. At any rate, I cannot doubt, nor did any one who was present during the fighting in the Mamund Valley, that the natives were aided by regular soldiers from the Afghan army, and to a greater extent by Afghan tribesmen, not only by the supply of arms and ammunition but by actual intervention.

I am not in possession of sufficient evidence to pronounce on the question of the Amir’s complicity in the frontier risings. It is certain, that for many years the Afghan policy has consistently been to collect and preserve agents, who might be used in raising a revolt among the Pathan tribes. But the advantages which the Amir would derive from a quarrel with the British are not apparent. It would seem more probable, that he has only tried throughout to make his friendship a matter of more importance to the Indian Government, with a view to the continuance or perhaps the increase of his subsidy. It is possible, that he has this year tested and displayed his power; and that he has desired to show us what a dangerous foe he might be, were he not so useful an ally. The question is a delicate and difficult one. Most of the evidence is contained in Secret State Papers. The inquiry would be profitless; the result possibly unwelcome. Patriotic discretion is a virtue which should at all times be zealously cultivated.

I do not see that the facts I have stated diminish or increase the probability of the Amir’s complicity. As the American filibusters sympathise with the Cuban insurgents; as the Jameson raiders supported the outlanders of the Transvaal, so also the soldiers and tribesmen of Afghanistan sympathised with and aided their countrymen and coreligionists across the border. Probably the Afghan Colonial Office would have been vindicated by any inquiry.

It is no disparagement but rather to the honour of men, that they should be prepared to back with their lives causes which claim their sympathy. It is indeed to such men that human advancement has been due. I do not allude to this matter, to raise hostile feelings against the Afghan tribesmen or their ruler, but only to explain the difficulties encountered in the Mamund Valley by the 2nd Brigade of the Malakand Field Force: to explain how it was that defenders of obscure villages were numbered by thousands, and why the weapons of poverty-stricken agriculturists were excellent Martini-Henry rifles.

The Mamunds themselves were now genuinely anxious for peace. Their valley was in our hands; their villages and crops were at our mercy; but their allies, who suffered none of these things, were eager to continue the struggle. They had captured most of the rifles of the dead soldiers on the 16th, and they had no intention of giving them up. On the other hand, it was obvious that the British Raj could not afford to be defied in this matter. We had insisted on the rifles being surrendered, and that expensive factor, Imperial prestige, demanded that we should prosecute operations till we got them, no matter what the cost might be. The rifles were worth little. The men and officers we lost were worth a great deal. It was unsound economics, but Imperialism and economics clash as often as honesty and self-interest. We were therefore committed to the policy of throwing good money after bad in order to keep up our credit; as a man who cannot pay his tradesmen, sends them fresh orders in lieu of settlement. Under these unsatisfactory conditions, the negotiations opened. They did not, however, interfere with the military situation, and the troops continued to forage daily in the valley, and the tribesmen to fire nightly into the camp.

At the end of the week a message from the Queen, expressing sympathy with the sufferings of the wounded, and satisfaction at the conduct of the troops, was published in Brigade orders. It caused the most lively pleasure to all, but particularly to the native soldiers, who heard with pride and exultation that their deeds and dangers were not unnoticed by that august Sovereign before whom they know all their princes bow, and to whom the Sirkar itself is but a servant. The cynic and the socialist may sneer after their kind; yet the patriot, who examines with anxious care those forces which tend to the cohesion or disruption of great communities, will observe how much the influence of a loyal sentiment promotes the solidarity of the Empire.

The reader must now accompany me to the camp of the 3rd Brigade, twelve miles away, at Nawagai. We shall return to the Mamund Valley and have a further opportunity of studying its people and natural features.