Editor’s Note: The following account by C. S. Forester is extracted from The 100 Best True Stories of World War II (published 1945). It was originally published in The Saturday Evening Post in 1944.

See also: The Sinking of the Scharnhorst: A German Perspective

In those almost forgotten days when there were pleasure cruises, we used to see posters advertising trips to The Land of the Midnight Sun. Of course, those were summer cruises; if any steamship company had been so foolish as to try to induce people to go to the North Cape in winter, they would have had to advertise, “The Land of the Midday Night.” On December 26 in those latitudes, seventy-five degrees north, the sun never comes above the horizon, and it is poor compensation to know it is circling not far below the horizon.

In ordinary weather it is never pitch dark. At noon it is a pale gray, and from noon it darkens imperceptibly until at midnight everything is dark gray. On a fair proportion of days and nights the green-and-yellow streamers of the aurora borealis give a fitful and erratic illumination. But there are just as many nights when the wind blows down from the Pole, tearing the tormented sea into lumpy mountains and engulfing the world in flurries of snow, so that the black sky gives no light and one cannot, literally, see one’s hand before one’s face.

Those are the times when it is not well to be a lookout, shivering in ten thicknesses of wool inside a sheepskin coat. The depth charges freeze to the decks; the breeches of the guns are covered with ice — unless precautions are taken — so that the breech-blocks cannot be opened; the lubrication of the ammunition hoists freezes solid. No ship can fight a battle in those wintry waters without special accessories for keeping the weapons clear of ice and for keeping life in the officers and men wedged, so they can hardly move, in the exposed gunnery-control stations.

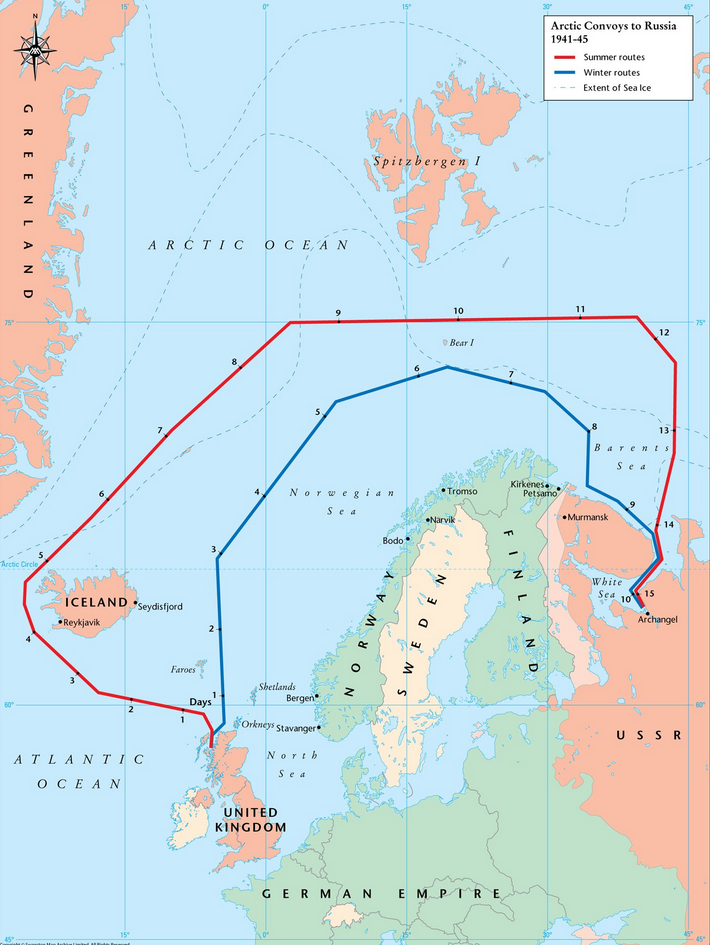

It is through these waters that the life line runs to Russia. The heavy convoys, laden with all the innumerable materials of war from the mines and factories of the world, make their way to Murmansk round the most northerly point of Norway. The farther north they keep, the longer is the journey they must make, at a time when even hours are important; the stormier are the seas they meet, and the greater are their chances of encountering ice. The farther south they keep, the quicker they make their run — and the more exposed they are to German attacks launched from Norway, above the surface of the sea, on the surface of the sea and below the surface of the sea.

Attacks by airplane and submarine, in present technical conditions, however, can only harass the convoys and not stop them. There is only one thing that could stop them, in fact, and that is superior sea power. If Germany had a fleet more powerful than that of the United Nations, not a convoy would move on the high seas, not a single ship, save for the occasional furtive blockade runners. But Germany does not have a superior fleet; she has a very inferior one. If the inferior fleet fights, it is destroyed. If it stays at home, it yields free use of the sea to the enemy, and might as well never have been built.

Between the two horns of this dilemma the weaker naval powers have always tried to find a profitable middle course. If the weaker power has a secure base within striking distance of the trade routes, the presence of its fleet there imposes certain troublesome precautions on the stronger power. It offers the threat of sallying out out at a moment of its own selection, so that every convoy moved by the superior power must be guarded by a force greater than the whole fleet of the inferior power, and that necessarily involves strain and potential loss — the strain of staying at sea and of replacing the fuel oil consumed, and the losses from submarines and from hazards of the sea.

But the threat must always be a real one. The weaker fleet must come out sometimes or it will find itself simply ignored. Moreover, mutinies breed readily in stagnant fleets, especially when the best of the men are steadily drained away for the submarine service. And even in a guarded base things can happen, as when the British midget submarine crept in and torpedoed the Tirpitz.

It was this loss which must have roused the Nazi government to desperation. The Russian offensive was rolling along unchecked. Something must be done at all costs to check the flow of supplies to her, before something should happen to the Scharnhorst as well. The Tirpitz was a wreck, only kept afloat by the constant attention of a salvage ship; the Gneisenau was in even worse condition at Gdynia. The Spee and the Bismarck had been sunk. Of Germany’s twenty-six destroyers, eleven were at the other end of Europe, waiting to bring in a blockade runner from the east. The Nazis could not foresee that in less than a week they would be foiled in their object and three of them sent to the bottom, and the blockade runner along with them. The straggling remainder of Germany’s navy was in the Baltic, for the possibility of the loss of the command of that sea to the Russian navy was something too horrible to contemplate.

Maybe the Nazis knew about the presence of that convoy to the north of the North Cape. Maybe a U-boat had sighted it and had radioed information of its position and course. Maybe some unguarded word spoken in a British port may have told a Nazi spy what he wanted to know. Maybe the Scharnhorst was sent out into the Arctic night on the mere chance of striking against something. At any rate, out she went from her Norwegian fjord, wearing at her masthead the flag — a black cross and two black balls on a white ground — of Rear Admiral Bey, commanding German destroyers.

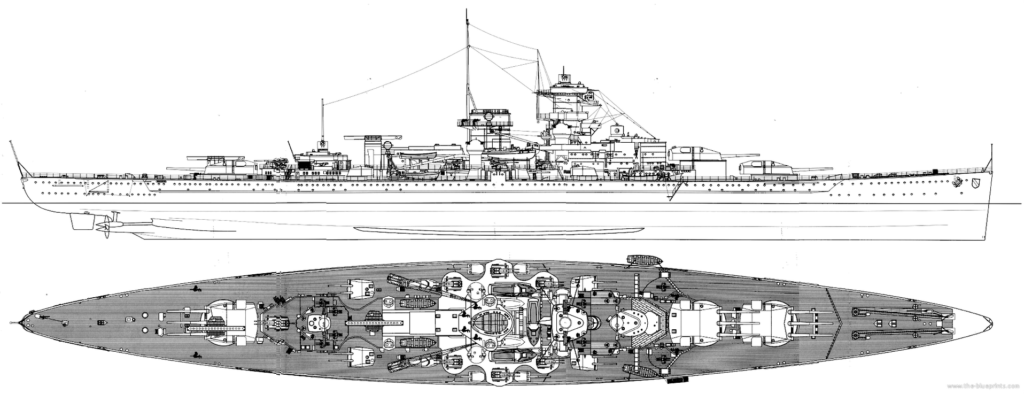

For the purposes of a raid she had all the desirable qualities. Designed for a speed of twenty-nine knots, she was faster — or so, at least, the Nazis hoped — than any British battleship. With nine 11-inch guns she was more powerful than any British cruiser; with her displacement of 26,000 tons she carried sufficient armor and was sufficiently compartmented to be able to receive a number of hard knocks without being crippled. And her enormous secondary armament of twelve 5.9-inch guns and fourteen 4.1’s would ensure that if she once got into a convoy she would sink ships faster than a fox killing chickens in a henroost.

At her high speed she could cover the whole distance in darkness, leaving her Norwegian fjord at the end of twilight one day and arriving in the area through which a convoy would be likely to pass at the beginning of twilight the next, so that she could be firing shells into helpless merchantmen before any British plane or submarine could detect her absence or catch a glimpse of her on passage. For closely associated reasons she had no destroyer escort; destroyers are running short in the Nazi navy; to give orders for destroyers to join her would give an additional chance for the Intelligence of the United Nations to get wind of the scheme; and, above all, a German ship steaming by herself on the high seas has the supreme advantage of the certainty that anything she sights is an enemy — she can open fire instantly, without having to wait for challenge and recognition.

She left on the afternoon of Christmas Day, and such was her good fortune or so accurate was her information that at precisely the right time, just when the gloomy northern sea was beginning to be faintly illumined and the dark gray of the sky was being replaced by something the merest trifle brighter, she made her contact with the convoy. There was any amount of shipping there, anything up to half a million tons. It was possible for her, in the next hour, to do as much damage as the whole U-boat navy could achieve in six months. In an hour she could put back the hands of the clock of war by four weeks.

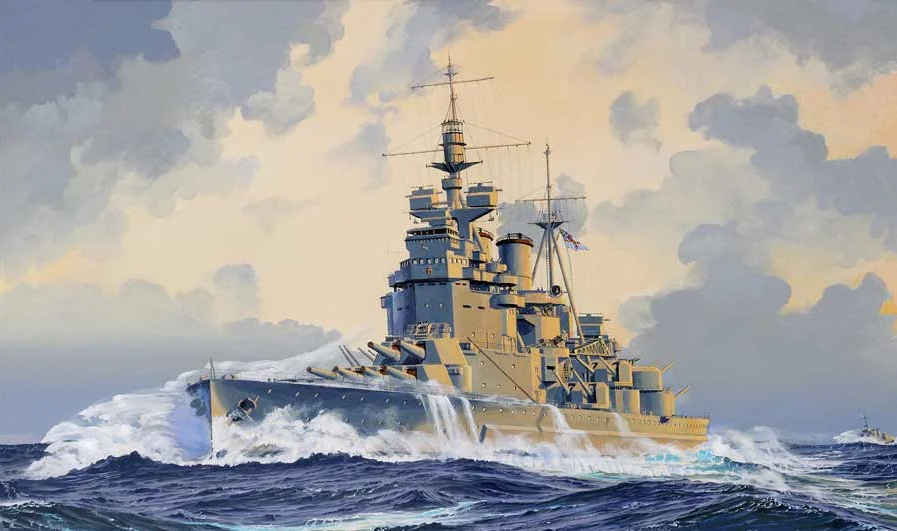

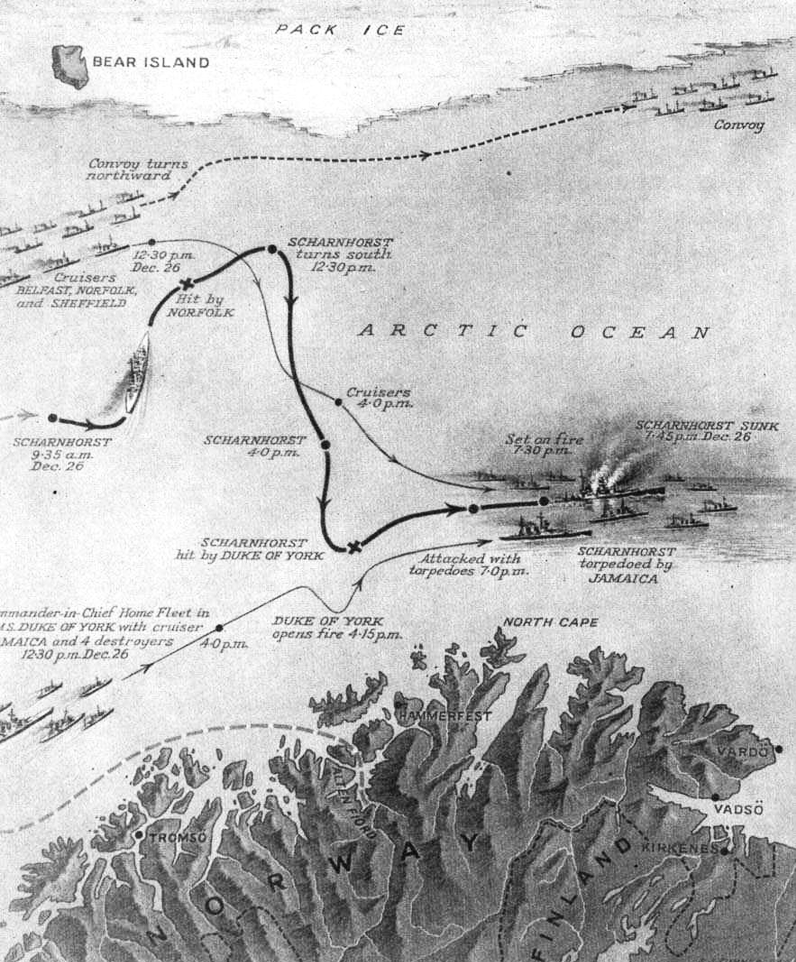

At 9:30 in the morning of the day after Christmas, the British convoy was heading east some 150 miles to the northward of North Cape. It was guarded against submarine attack by a ring of corvettes and destroyers, small craft, twenty of which together would hardly equal the Scharnhorst in size. That was the anti-submarine protection; to guard against attack by surface vessels, Admiral Burnett had three cruisers, Belfast, Norfolk and Sheffield. The southeast was the most dangerous quarter, from which attack was most likely to come, so that it was to the southeast of the convoy that Burnett had stationed his squadron, and it was from the southeast that Bey arrived.

It could not be called bad luck that the Scharnhorst’s first contact was made with the escort instead of with the helpless merchant ships. She could expect nothing else, for the British cruisers and destroyers covering the convoy must be disposed in a manner to guard against any possible attack. It might be considered possible for her, with all the advantage of surprise, to crash through the screen and plunge in among the unarmed ships which were her real objective. It would be dangerous, for there is great danger in approaching too close to an enemy who is still in a condition to launch torpedoes. Bey had hardly more than seconds in which to make up his mind whether he should make the attempt. The Scharnhorst and the British escort sighted each other at six miles. A thousand yards short of that distance, decisive torpedo range begins, and battleship and escort hurtling together would close the range by 1,000 yards in less than a minute.

Aboard the British ships, the unsleeping eye which all United Nations ships carry — the eye that can see in the dark, can see through the Arctic night, through fog or snowstorm — had been watching over their safety. It had given the first alarm, and now was reporting to bridge and to gunnery-control tower just where this intruder, this almost certain enemy, was to be found a whither she was headed. The guns were training round in accordance with its observations, and the gunnery officers in their control towers were eyeing the “gun-ready” lamps and awaiting the moment to open fire.

It was as if the shepherd’s dogs, guarding the flock, had scented the approach of the wolf, and had rushed forward to put themselves between the wolf and the flock, baying the warning which the masthead signal lamps sent through the twilight to the commodore of the convoy. Ponderously, in obedience to the commodore’s orders, the convoy turned itself about — not an easy thing to do with heavy columns of unhandy merchant ships — while the Norfolk, the Sheffield and the Belfast went dashing forward to meet the enemy.

In a broadside or in a given interval of time, the Scharnhorst could fire more than the weight of shells that could be fired by the three cruisers all put together. It would be a fortunate light cruiser that could sustain a hit from one of the 11-inch shells of the Scharnhorst and live through it. The armor that the Scharnhorst carried over her vitals could be relied upon to keep out the cruisers’ shells at all but the closest range. Mathematically, the approaching conflict was to the last degree unfair.

Yet in war at sea mathematics plays, even in these days of machinery, only a minor part. There are the discipline and training of the crews to be taken into account, the experience and resolution of the captains, and, above all, there is chance — the chance that will take a ship unscathed through a hail of salvos, the chance that will direct a shell to the one point where it will rend a ship in two, the chance that will direct a desperate torpedo to its mark.

The three cruisers flung themselves upon the Scharnhorst. Twenty-six thousand tons tearing through the rough sea at thirty knots displace a prodigious amount of water. Even though in that gloomy twilight — 9:30 A.M., and very little light creeping round the curve of the earth as yet — the glittering white bow wave flung up by the Scharnhorst could be seen even when her grey upper works were invisible. A gun was fired in the British squadron and a star shell traced a lovely curve of white light through the twilight before it burst fairly over the battle cruiser, lighting up her and the sea for a mile around her more brightly than any winter noontime in those latitudes. It hung in the sky like the Star of Bethlehem at another Christmastide as its parachute sustained it in the air seemingly without falling at all, and, as it hung, the cruisers’ guns opened fire on the target.

The shells went screaming on their mission — long range for 6-inch, only medium range for 11-inch — and the spotting officer of the Norfolk, staring through his glasses, saw, just at that very second when the Norfolk’s shells should land, a vivid green flash from the Scharnhorst’s black hull. The Norfolk carried 8-inch guns — the other crusiers only 6-inch — and there was a chance — although not a very big one — that the Scharnhorst might be badly hurt.

The Scharnhorst spun about so rapidly that the next salvo fell harmlessly into the sea where she would have been had she maintained her course, and dashed out of the illuminated circle. When ships are six miles apart and traveling at a combined speed of sixty miles an hour touch is broken as quickly as it can be made. She vanished into the twilight.

Bey is dead now. We do not know, and very likely we shall never know, what were the motives that induced him to turn away. It is just possible that he was deterred by the sight of the three British cruisers flinging themselves upon him like a trio of wildcats — possible but hardly probable. It is not likely that a man could rise to admiral’s rank in the Nazi navy if he were of the stuff that flinches. The hit that the Norfolk scored may have caused enough damage to force him to turn, but it takes time — several seconds, if not more — for details of damage to be ascertained and reported to the bridge, and it seems certain that the Scharnhorst turned away the moment she was hit.

Most likely, Bey was acting on a plan he had devised long beforehand. It was the convoy he was after. He did not want to fight ships of war and risk damage to his precious battleship unless circumstances compelled him to do so. If he stayed and fought it out with the three cruisers, there was a chance that the Scharnhorst might be hit and crippled; in another two minutes there would be eighteen torpedoes launched from the cruisers’ decks and hurtling toward him, and any one of those might slow him up enough to incapacitate him. He thought the odds were not profitable in terms of the stake, and he withdrew.

He knew now where were the main defenses of the convoy, and he could guess with some accuracy where the merchant ships themselves were to be found. He could circle away, losing himself in the gloom, and then, turning back, he could make a fresh stab which ought to slip past the British guard.

Admiral Burnett was in command of the British cruiser force, with his flag flying on the Belfast. A sailor of vast experience, this was by no means the first convoy which he had escorted to Murmansk. But now he was presented with no mere problem of navigation or seamanship. No rule of thumb could be of the least assistance to him in this present situation. What he had to do was to guess what Bey would do next. Anybody could be quite certain that Bey’s one aim was to get in among the merchant ships, but to guess where and when he would make his attack was something that was far more difficult to foresee.

A thirty-knot battleship tearing through the gloom could sweep in an hour all round the convoy at a distance which would make her safe from detection, even by the instruments which the British ships carried. It would take the Scharnhorst no more than five minutes to come in over the horizon within range of the merchant vessels and no more than five minutes after that, as has already been said, to wipe out a month’s effort by all the factories in the world. So there was no margin whatever for miscalculation on the part of the British; Burnett had to put himself in the path of the Scharnhorst’s next attack, and that attack might come from north or east or west or south.

If it should come from the east when Burnett was in the west, the British cruisers might as well be in the Pacific for any protection they could give to the merchant ships. It was not a question of having to guess which of two possible courses Bey would adopt; it was a question of guessing which of some sixteen courses. Burnett had to guess within a very few degrees on what bearing Bey would reappear over the horizon, and he had to have his cruisers there. It was strictly his problem — a one-man decision. The staff of the Admiralty, reading off the scrappy wireless intercepts, might be able to offer him advice, but they could not relieve him of the responsibility. He had a purely intellectual problem to solve as he stood on the crowded and exposed bridge, with the spray flying aft as the Belfast tore at top speed over the heaving sea.

He solved it. It was 9:30, the beginning of the winter day, when the Scharnhorst made her first contact with the cruisers from the southeast. At 12:30 — high noon — the Scharnhorst reappeared from the northeast, to find Burnett and his cruisers right in her path. It was an extraordinary achievement on Burnett’s part, seeing that the Scharnhorst could have appeared anywhere along the circumference of a circle of at least 100 miles; her speed, well over twice that of the convoy, gave her, of course, complete liberty of action. What Bey thought of this extraordinary apparition of three indomitable cruisers right in his path when by all the laws of chance they should have been twenty miles away can be guessed from his actions. There was a sudden flurry of salvos, during which a single shell landed and burst on the Norfolk’s stern, and then Bey turned and ran for home.

It was dangerous for him to stay out longer. Three hours had elapsed since the British had first become aware that the Scharnhorst was out. It would take another hour or two, at least, of maneuvers if he were to make another attempt to strike at the convoy without fighting his way through, and the arguments against fighting his way through were as cogent now as they had been three hours earlier. He did not wish to risk being cut off from his base, and if he headed for home now, he had just sufficient time to reach his protecting fjord before next morning’s daylight. He could not doubt that three hours ago, the moment Burnett first sighted him, hurried messages had been broadcast to the British Admiralty and to the main British fleet; nor could he doubt that the British were at this moment straining every nerve to send ships and aircraft to guard their precious convoy and to attack a ship as valuable as the Scharnhorst.

As a matter of fact, there was far more risk than he knew. One hundred and fifty miles to the southwest of him, and steaming fast to cut him off, was a force which could make scrap iron of his ship. This was the Duke of York with her attendant cruiser, the Jamaica, and her screen of four destroyers. From her masthead flew the St. George’s cross of a full admiral — no less a person than Sir Bruce Fraser, commander in chief of the Home Fleet. Nobody outside of a few favored persons knows how many times the patient Royal Navy had set that trap, how many times a battleship force had plodded along from England to Russia on a course parallel to, but well away from, that of the convoy, in the hope of intercepting any Nazi force sent out from Norway. Probably it had been done over and over again, and this was the first time that patience and resolution were to be rewarded.

Fraser, in the Duke of York, was about 200 miles away from the convoy when, at 9:30, came Burnett’s first message of the appearance of the Scharnhorst. There would have been nothing gained, and the risk of much being lost, if he had been any nearer. The wary and elusive enemy had an advantage in speed of several knots. Fraser had to be sure of being able to interpose between the Scharnhorst and her base; any mere pursuit was doomed to failure before it started.

Not that there was any certainty about cutting the enemy off from his base. The sea is wide and the Arctic night can be intense. Unless Fraser was able to place himself squarely across the Scharnhorst’s path, there was every chance that she would slip past him. Hence during that Sunday morning while Burnett was wondering where the Scharnhorst would reappear, Fraser was having to decide upon his own course of action. He sent his men to action stations, and at increased speed he and his cruiser and destroyers headed toward the strategic center of gravity the nearest point of a straight line between the Scharnhorst’s last known position and the German base.

In the British battleship, as in every other ship, the only men who moved from their posts during that day were those sent down to the galleys to fetch their comrades’ dinners. It was a Sunday dinner — soup, pork chops and baked potatoes — and this the men ate at their posts, squatting on the heaving decks, jammed closely in the turrets and shell rooms or swaying about in the gunnery control towers 100 feet above the surface of the sea.

Dinner had hardly been eaten in these uncomfortable circumstances when the next flash of news came from Burnett; the Scharnhorst had made her second appearance, and Fraser now knew her exact position again. She was still 150 miles away, Fraser was nearer to her base than she was, but it was certain that contact would only be made — if it was made at all — in three or four hours’ time, long after twilight had ceased.

It was time for Burnett to distinguish himself again. The Scharnhorst, after scoring her hit on the Norfolk, had headed south through the twilight. Burnett swung his ships to starboard in pursuit. It was of the utmost importance that Fraser should be kept informed of the Scharnhorst’s course and position, so that he could place himself to meet her as she came down from the north. Burnett had to keep in touch with the Scharnhorst, but to keep in touch with a ship that mounts nine 11-inch guns is more easily asked than done. Those 11-inch guns were capable of hitting a target clean over the horizon, farther than the eye could see, and it needed only one of those salvos, landing square, to smash any one of the frail cruisers into a sinking wreck.

During that anxious afternoon the listeners at the Admiralty took in message after message which told them of how Burnett was maintaining contact, and on their charts they could prick off the Scharnhorst’s position as she came nearer to the safety of the Norwegian coast. They knew that somewhere in that neighborhood was the commander in chief, steering steadily eastward in grim wireless silence. So far, he had done nothing to reveal his position, for he knew perfectly well that a score of stations in Norway and Germany were eagerly taking in every message that passed over the ether, even if they were unable to decipher them. One whisper from the Duke of York’s radio and the direction-finding stations would locate it instantly, and the transmitting stations would flash the news to the Scharnhorst of the presence of another British force — strength unknown, but obviously to be avoided — to the southwest of him. But the Germans did not know Fraser was at sea; Bey did not know; and although Burnett and the Admiralty knew he was at sea, they did not know where he was. They could only hope.

Then all doubts were suddenly resolved in one glorious moment. The Duke of York broke her wireless silence, and the message which the Admiralty listeners took in was an order from Fraser to “illuminate the enemy with star shell.” Then they knew that Fraser’s calculated position was very close to the position which Burnett was reporting for the Scharnhorst. The Duke of York’s navigating officers had done a neat professional job. Counting every turn of their ship’s propellers, making allowance for current and wind, they had fixed their own position accurately on the chart. At the same time they had deduced from Burnett’s reports what was the Scharnhorst’s course and what would be her present position. Burnett’s navigators had been equally brilliant, for they could only report the Scharnhorst’s position with reference to their own calculated position. It should be remembered that at Jutland in World War I, over distances not nearly so great, Jellicoe and Beatty miscalculated their relative positions with a total error of seven miles and serious results to Jellicoe’s deployment. An error of seven miles in the present circumstances would give the Scharnhorst every chance of dashing by unharmed.

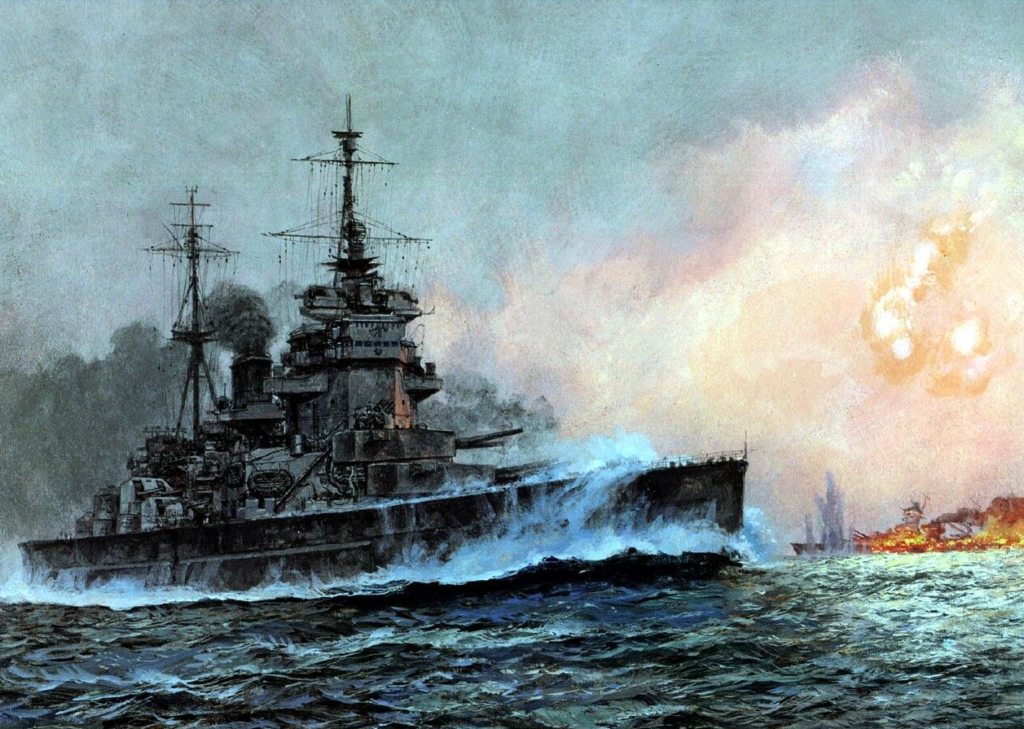

It was 4:30, quite dark, when Fraser broke wireless silence and the warning gong sounded in the Duke of York. The Scharnhorst was on his port bow, and the Belfast was eight miles astern of the Scharnhorst. Before the Scharnhorst’s wireless telegraphists, having heard the Duke of York signaling, could have communicated to Bey on the bridge the appalling news of an enemy close ahead, the fifth act of the tragedy — played throughout in the dark, like Macbeth — had begun. A streak of white fire shot from one of the Belfast’s guns and soared against the black sky, eight miles in twenty seconds. The shell burst high up, with a faint report unnoticeable in the blustery night, and then the tremendous white flare blazed out, sinking slowly under its supporting parachute and lighting up the scene over a two-mile radius.

Right in the center of that blaze of white light was the Scharnhorst, and the lookouts and spotters and gunnery officers in Fraser’s force saw her upper works brightly lit, standing out boldly against the horizon. The rating at the director sight trained his instrument upon her; the 14-inch guns moved their thousands of tons of dead weight round in obedience to its dictation, and when the gunnery officer said “Open fire,” five 14-inch guns roared out with the incredibly loud din of their kind and sent three and a half tons of shells — three and half tons of hot steel and high explosive — at their mark. For a score of seconds the shells rumbled through the air; one of the destroyers in the Duke of York’s screen under the arch of their trajectory heard them pass overhead like maddened express trains.

Then they landed, flinging up their 200-foot splashes under the unearthly illumination of the star shell. So closely had the range been estimated that this first salvo was registered as a “straddle,” with some shells falling this side of the mark and some the other. And the next salvo, following less than a half minute later, recorded a hit. At least one shell, of three quarters of a ton weight, had struck home on the Scharnhorst, so that there were Germans on board who were killed without even knowing of the sudden dramatic appearance of a British battleship on the Scharnhorst’s starboard bow.

Chance dictated that she should be struck without being disabled. Half a minute elapsed between the moment when the Duke of York was illuminated by the blaze of fire from her gun muzzles and the moment when the Scharnhorst staggered under the titanic blow of the striking shell; that half minute was long enough for Bey to grasp the implications of those gun flashes on the horizon and to give the order which spun the Scharnhorst’s wheel hard aport and sent her wildly seeking safety in the eastward darkness.

The Scharnhorst sped eastward with every revolution her engineers could wring from her turbines, and after her came the British ships. There was still hope, for Bey knew he had an advantage of several knots in speed over any British battleship. In two hours’ flight he could be out of range, and in darkness and at those colossal speeds there was nothing fantastic in hoping that his ship would avoid fatal injury for that time — to say nothing of the fact that his own fire might disable his enemy first. He turned his stern square to the pursuer, thereby at the same time presenting the smallest possible target and making the best use of his difference of speed, and he trained aft those of his guns that would bear, fired a star shell, and began a methodical return fire upon the Duke of York.

His hope of hitting the Duke of York on her water line or in her engines, and thereby slowing her down, came to nothing, but but one of his shells scored a hit which might have proved equally important. Fragments struck the mast, and one of them cut away the wireless aerial. By that stroke the commander in chief of the Home Fleet was sundered from communication with the rest of the world and was rendered unable to either coordinate the action of the four cruisers and the four destroyers under his command or to report his position and progress. Had the Duke of York remained unable to give orders to the destroyers, the Scharnhorst might possibly have survived. But Lieutenant H. R. J. Bates effected a temporary repair in the quickest possible way. He climbed the mast — in the dark, with the wind whipping round him and the ship lurching fantastically over the waves — and he held the ends of the aerial together for the orders to pass. Eleven-inch shells were being fired at the ship while he did so, and the splashes from near misses rose to his level.

The Scharnhorst survived the broadsides of the Duke of York for more than an hour, and although she was hit and hit again, she was not wounded sufficiently to make any immediate difference to her speed. The time interval had been long enough for her to increase her distance from the Duke of York for the moment. But hardly had the exasperated gunnery officer in the Duke of York given the word to cease fire when a new blaze of gunfire lit the horizon far ahead where the Scharnhorst had last been seen. She was having to defend herself against new enemies.

The four destroyers of the Duke of York’s screen, Savage, Saumarez, Scorpion and Stord — the last a vessel of the Norwegian navy — found themselves, when the action began between the two battleships, ahead of the Duke of York and astern of the Scharnhorst. Their superiority of speed enabled them to head-reach upon the Scharnhorst even while the Scharnhorst was drawing away from the Duke of York. The Savage and Saumarez overhauled her on the starboard side, the Scorpion and Stord on her port side. In that hour and a half they were able to sweep right around her and then dash in, two on either bow – torpedo attacks, to be effective, must be launched from ahead of the target.

The attacks were made in the nick of time, just as the Scharnhorst escaped from the battleship’s guns. The Scharnhorst saw them and opened fire with all the innumerable guns of her secondary battery, but destroyers charging in at forty knots from opposite sides are hard to stop. Moreover, she had been hard hit by half a dozen heavy shells, with the almost certain result of damage to her guns and system of communications.

It seems that at this very moment her speed suddenly fell to twenty knots as the result of injuries inflicted on her by the Duke of York’s guns; at a guess, a condenser had been damaged and a boiler eventually put out of action by the entrance of salt water. From a spectacular point of view, her defense was dramatic enough. She was one vast glow from the orange-red flames of her guns, and from this central nucleus radiated the innumerable streaks of tracer shells — tracers that she was firing at the destroyers and tracers which every ship arriving in range fired back at her.

Yet her fire was singularly ineffective. Only the Saumarez was hit, and although the damage to the destroyer’s upper works resulted in regrettable casualties, her fighting value was not greatly impaired. The destroyers pressed home their attack to the uttermost limit. They did not loose their torpedoes at the 10,000-yard range which is the torpedo’s maximum, nor at the 6,000 yards which experience has sometimes shown to be the nearest a destroyer can hope to approach a well-defended capital ship. They pressed in to 2,000 yards and less, launched their torpedoes, and then, with their wheels hard over, sheered away from the doomed battleship.

Several torpedoes — how many there is no means of knowing — struck home, but the battle flared up with even greater violence. One singular advantage which the German navy has always possessed was clearly demonstrated at this crisis. As the weaker naval power, she has never had to design her ships for ability to keep the sea for long periods of time; swift and sudden blows were all she expected of them, with the result that habitability is not considered a necessity. They can lie in harbor with their crews on shore in barracks most of their time, so that they can be compartmented in a fashion impossible to British or American ships. The Scharnhorst survived these several underwater blows and maintained a tremendous volume of fire, comparatively ill-directed but impressive.

With the Scharnhorst falling off in speed, the Duke of York came up in range again, and the 14-inch guns began to smash her to pieces. At the same time every British ship closed in and opened fire. The Duke of York’s attendant cruiser, Jamaica, which had been firing intermittently during the whole easterly run, drew up on one side of her to use her 6-inch guns at point-blank range. Burnett and his three cruisers pressed in on the other, and the wretched ship, unable any longer to keep her fires under control, blazed out in a sudden volcano of flame even while she maintained her return fire, dropping several shells close to the Duke of York.

Nor were these her only assailants, for there now arrived on the scene four more destroyers, part of the convoy escort, who, having made sure that no other enemy was likely to attack their charges, came dashing down with proper military instinct to where the battle was taking place. There was danger of effort being wasted by all this concentration of force. It is impossible for gunfire to be properly directed when several ships are firing on one target in uncoordinated fashion. In the pitch darkness no fewer than eight destroyers, four cruisers and a battleship were tearing about at their highest speed round the Scharnhorst. Torpedoes were being launched and guns were being fired by eager captains anxious to be in at the kill. British fighting blood was aflame. Hotheads might be carried away by their own enthusiasm, and it was time for the master hand to take control again. The signal sent out by the commander in chief can be given in its entirety because, owing to the urgency of the occasion, it was in plain English, so publication gives the Nazis no chance of breaking the British code.

The message was perfectly calm and methodical, betraying no sign of the excitement of the moment. “Clear the area of the target,” it said, “except for those ships with torpedoes and one destroyer with searchlight.” It was like the bugles blowing for the death at a bullfight. The arena was cleared as the ships obeyed orders and sheered away. One destroyer trained her searchlights on the wreck – long, long pencils of intense white light reaching for miles through the darkness – and the Jamaica came in like a matador for the kill. She swung around and a salvo of torpedoes leaped from her deck and began their fifty-mile-an-hour run toward toward the target. At that very moment a great billow of smoke eddied out from the Scharnhorst’s sides and hid her, but the Jamaica put her helm over and sent another salvo of torpedoes hurrying after the first.

With the tremendous explosions when they hit the mark, the smoke cleared away, and the Scharnhorst was revealed for the last time, on her side, with her bottom exposed, and yet with the flames of her ammunition fires still spouting from her. Then the smoke closed round her again and she went to the bottom, while the British cruisers raced in to try to pick up survivors. There is on record the comment made by one of the British sailors who went into that smoke, but it is not well to repeat it. More than 1,000 men had burnt in those flames.

It is hard to criticize the Nazi tactics or the Nazi strategy. The Scharnhorst came out and was destroyed, yet if she had stayed at home the naval historian of the future would have condemned the Nazi High Command for her inactivity. She refused to face Burnett’s wildcat attack at the opening of the day, although we now know that nothing worse could have happened to her than actually did happen, and she hardly could have inflicted less damage than she actually did inflict. If she had fought Burnett she might have been disabled and sent to the bottom, leaving us to comment that a more cautious commander would have withdrawn, as soon as he was discovered, and got clean away.

Yet the Nazi sailor who is ordered out will remember the Spee and the Bismarck and the Scharnhorst, and will go with a reluctance that will not increase his efficiency. And the Japanese, on the other side of the world, must have heard of the loss of the Scharnhorst with dismay, for it meant that at least one more British battleship was free to make the voyage east and add to the pressure of sea power that will slowly constrict Japan to her death.

Thanks for these good stories from history.

interesting the elisions required in Forrester’s telling of the tale, due to National Security concerns.

.

it was, of course, no particular feat of seamanship on Fraser’s part, he needed only follow the reports from his superior radar equipment.

.

the statement that the Scharnhorst was located by observation of the bow wave and that the salvos followed subsequent to the starshell are obviously complete fabrications, is also intended to obscure the role of radar.

.

they do have a reputation to live up to in Perfidious Albion.