Editor’s note: This is the last in a series of twelve lectures by Charles Kingsley, published as The Roman and the Teuton (1889).

(Go back to Lecture XI: The Popes and the Lombards)

I do not know whether any of you know much of the theory of war. I know very little myself. But something of it one is bound to know, as Professor of History. For, unfortunately, a large portion of the history of mankind is the history of war; and the historian, as a man who wants to know how things were done—as distinct from the philosopher, the man who wants to know how things ought to have been done—ought to know a little of the first of human arts—the art of killing. What little I know thereof I shall employ today, in explaining to you the invasion of the Teutons, from a so-called mechanical point of view. I wish to shew you how it was possible for so small and uncivilized a people to conquer one so vast and so civilized; and what circumstances (which you may attribute to what cause you will: but I to God) enabled our race to conquer in the most vast and important campaign the world has ever seen.

I call it a campaign rather than a war. Though it lasted 200 years and more, it seems to me (it will, I think, seem to you) if you look at the maps, as but one campaign: I had almost said, one battle. There is but one problem to be solved; and therefore the operations of our race take a sort of unity. The question is, how to take Rome, and keep it, by destroying the Roman Empire.

Let us consider the two combatants—their numbers, and their position.

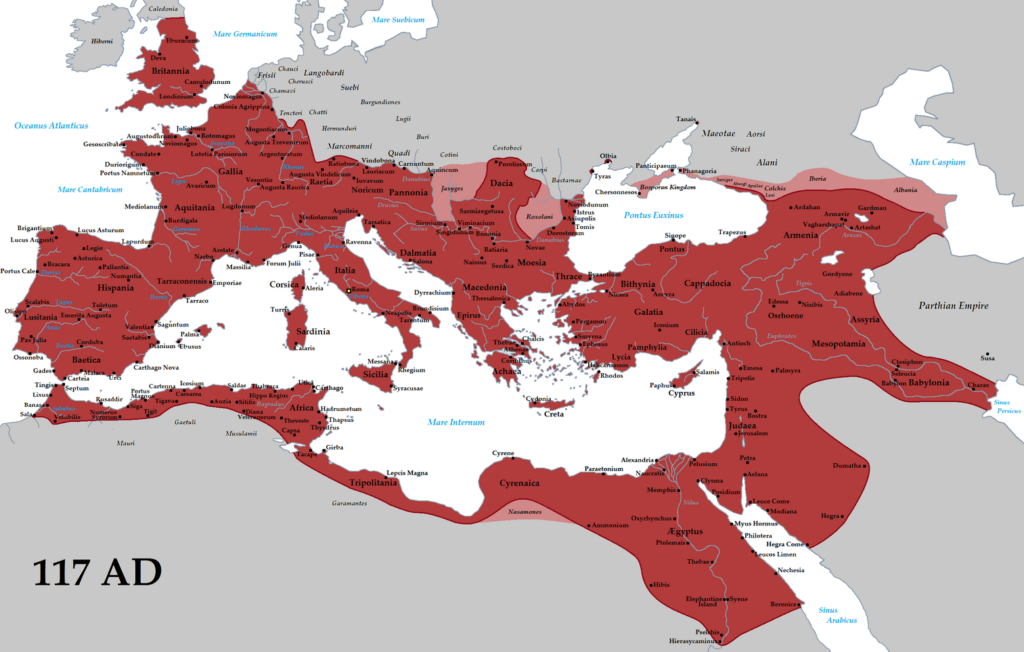

One glance at the map will shew you which are the most numerous. When you cast your eye over the vastness of the Roman Empire from east to west—Italy, Switzerland, half Austria, Turkey and Greece, Asia Minor, Syria, Egypt, North Africa, Spain, France, Britain—and then compare it with the narrow German strip which reaches from the mouth of the Danube to the mouth of the Rhine, the disparity of area is enormous; ten times as great at least; perhaps more, if you accept, as I am inclined to do, the theory of Dr. Latham, that we were always ‘Markmen,’ men of the Marches, occupying a narrow frontier between the Slavs and the Roman Empire; and that Tacitus has included among Germans, from hearsay, many tribes of the interior of Bohemia, Prussia, and Poland, who were Slavs or others; and that the numbers and area of our race has been, on Tacitus’ authority, greatly overrated.

What then were the causes of the success of the Teutons? Native courage and strength?

They had these: but you must recollect what I have told you, that those very qualities were employed against them; that they were hired, in large numbers, into the Roman armies, to fight against their own brothers.

Unanimity? Of that, alas! one can say but little. The great Teutonic army had not only to fight the Romans, but to fight each brigade the brigade before it, to make them move on; and the brigade behind it likewise, to prevent their marching over them; while too often two brigades quarrelled like children, and destroyed each other on the spot.

What, then, was the cause of their success? I think a great deal of it must be attributed to their admirable military position.

Look at a map of Europe; putting yourself first at the point to be attacked—at Rome, and looking north, follow the German frontier from the Euxine up the Danube and down the Rhine. It is a convex arc: but not nearly as long as the concave arc of the Roman frontier opposed to it. The Roman frontier overlaps it to the north-west by all Britain, to the south-west by part of Turkey and the whole of Asia Minor.

That would seem to make it weak, and liable to be outflanked on either wing. In reality it made it strong.

Both the German wings rested on the sea; one on the Euxine, one on the North Sea. That in itself would not have given strength; for the Roman fleets were masters of the seas. But the lands in the rear, on either flank, were deserts, incapable of supporting an army. What would have been the fate of a force landed at the mouth of the Weser on the north, or at the mouth of the Dnieper at the west? Starvation among wild moors, and bogs, and steppes, if they attempted to leave their base of operations on the coast. The Romans saw this, and never tried the plan. To defend the centre of their position was the safest and easiest plan.

Look at this centre. It is complicated. The Roman position is guarded by the walls of Italy, the gigantic earthwork of the Alps. To storm them, is impossible. But right and left of them, the German position has two remarkable points—strategic points, which decided the fate of the world.

They are two salient angles, promontories of the German frontier. The one is north-east of Switzerland; the Allman country, between the head-waters of the Danube and the Upper Rhine, Basle is its apex. Mentz its northern point, Ratisbon its southern. That triangle encloses the end of the Schwartzwald; the Black Forest of primæval oak. Those oaks have saved Europe.

The advantages of a salient angle of that kind, in invading an enemy’s country, are manifest. You can break out on either side, and return at once into your own country on ‘lines of interior operation;’ while the enemy has to march round the angle, three feet for your one, on ‘lines of exterior operation.’ The early German invaders saw that, and burst again and again into Gaul from that angle. The Romans saw it also (admirable strategists as they were) and built Hadrian’s wall right across it, from the Maine to the Danube, to keep them back. And why did not Hadrian’s wall keep them back? On account of the Black Forest. The Roman never dared to face it; to attempt to break our centre, and to save Italy by carrying the war into the heart of Germany. They knew (what the invaders of England will discover to their cost) that a close woodland is a more formidable barrier than the Alps themselves. The Black Forest, I say, was the key of our position, and saved our race.

From this salient angle, and along the whole Rhine above it, the Western Teutons could throw their masses into Gaul; Franks, Vandals, Alans, Suevi, following each other in échellon. You know what an échellon means? When bodies of troops move in lines parallel to each other, but each somewhat in the rear of the other, so that their whole position resembles an échelle—a flight of steps. This mode of attack has two great advantages. It cannot be outflanked by the enemy; and he dare not concentrate his forces on the foremost division, and beat the divisions in detail. If he tries to do so, he is out-flanked himself; and he is liable to be beaten in detail by continually fresh bodies of troops. Thus only a part of his line is engaged at a time. Now it was en échellon, from necessity, that the tribes moved down. They could not follow immediately in each other’s track, because two armies following each other would not have found subsistence in the same country. They had to march in parallel lines; those nearest to Italy moving first; and thus forming a vast échellon, whose advanced left rested on, and was protected by, the Alps.

But you must remember (and this is important) that all these western attacks along the Rhine and Rhone were mistakes, in as far as they were aimed at Rome. The Teutons were not aware, I suppose, that the Alps turned to the South between Gaul and Italy, and ran right down to the Mediterranean. There they found themselves still cut off from Rome by them. Hannibal’s pass over the Mont Cenis they seem not to have known. They had to range down to the Mediterranean; turn eastward along the Genoese coast at Nice; and then, far away from their base of operations, were cut off again and again, just as the Cimbri and Teutons were cut off by Marius. All attempts to take Rome from the Piedmontese entrance into Italy failed. But these western attacks had immense effects. They cut the Roman position in two.

And then came out the real weakness of that great ill-gotten Empire, conquered for conquering’s sake. To the north-west, the Romans had extended their line far beyond what they could defend. The whole of North Gaul was taken by the Franks. Britain was then isolated, and had to be given up to its fate. South Gaul, being nearer to Italy their base, they could defend, and did, like splendid soldiers as they were; but that defence only injured them. It thrust the foremost columns of the enemy on into Spain. Spain was too far from their base of operation to be defended, and was lost likewise, and seized by Vandals and Suevi. The true point of attack was at the other salient angle of our position, on the Roman right centre.

You know that the Danube as you ascend it lies east and west from the Black Sea to Belgrade; but above the point where the Save enters it, it turns north almost at right angles. This is the second salient point; the real key of the whole Roman Empire. For from this point the Germans could menace—equally, Constantinople and Turkey on the right (I speak always as standing at Rome and looking north), and Italy and Rome on the left. The Danube once crossed, between them and Constantinople was nothing but the rich rolling land of Turkey; between them and Rome nothing but the easy passes of the Carnic Alps, Laybach to Trieste. Trieste was the key of the Roman position. It was, and always will be, a most important point. It might be the centre of a great kingdom. The nation which has it ought to spend its last bullet in defending it.

The Teutons did cross the Danube, as you know, in 376, and had a great victory, of which nothing came but moral force. They waited long in Moesia before they found out the important step which they had made. The genius of Alaric first discovered the key of the Roman position, and discovered that it was in his own hands.

I do not say that no Germans had crossed the Laybach pass before him. On the contrary, Markmen, Quadi, Vandals, seem to have come over it as early as 180, and appeared under the walls of Aquileia. Of course, some one must have gone first, or Alaric would not have known of it. There were no maps then, at least among our race. Their great generals had to feel their way foot by foot, trusting to hearsays of old adventurers, deserters, and what not, as to whether a fruitful country or an impassable alp, a great city or the world’s end, was twenty miles a-head of them. Yes, they had great generals among them, and Alaric, perhaps, the greatest.

If you consider Alaric’s campaigns, from A.D. 400 to A.D. 415, you will see that the eye of a genius planned them. He wanted Rome, as all Teutons did. He was close to Italy, in the angle of which I just spoke; but instead of going hither, he resolved to go south, and destroy Greece, and he did it. Thereby, if you will consider, he cut the Roman Empire in two. He paralysed and destroyed the right wing of its forces, which might, if he had marched straight for Italy, have come up from Greece and Turkey, to take him in flank and rear. He prevented their doing that; he prevented also their succouring Italy by sea by the same destruction. And then he was free to move on Rome, knowing that he leaves no strong place on his left flank, save Constantinople itself; and that the Ostrogoths, and other tribes left behind, would mask it for him. Then he moved into Italy over the Carnic Alps, and was repulsed the first time at Pollentia. He was not disheartened; he retired upon Hungary, waited five years, tried it again, and succeeded, after a campaign of two years.

Yes. He was a great general. To be able to move vast masses of men safely through a hostile country and in face of an enemy’s army (beside women and children) requires an amount of talent bestowed on few. Alaric could do it. Dietrich the Ostrogoth could do it. Alboin the Lombard could do it, though not under such fearful disadvantages. There were generals before Marlborough or Napoleon.

And do not fancy that the work was easy; that the Romans were degenerate enough to be an easy prey. Alaric had been certainly beaten out of Italy, even though the victory of Pollentia was exaggerated. And in 405, Radagast with 200,000 men had tried to take Rome by Alaric’s route, and had simply, from want of generalship, been forced to capitulate under the walls of Florence, and the remnant of his army sold for slaves.

Why was Alaric more fortunate? Because he was a great genius. And why when he died, did the Goths lose all plan, and wander wildly up Italy, and out into Spain? Because the great genius was gone. Native Teuton courage could ensure no permanent success against Roman discipline and strategy, unless guided by men like Alaric or Dietrich.

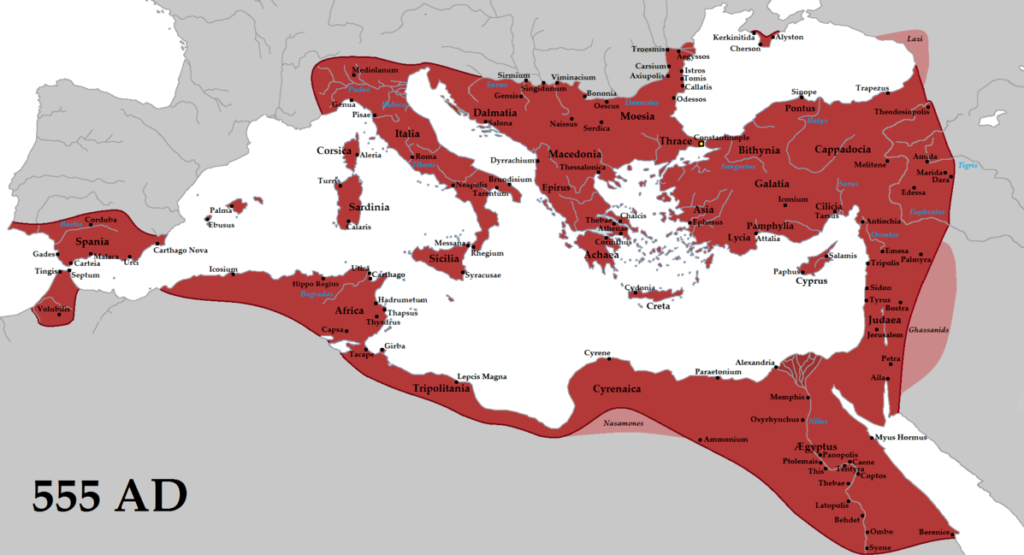

You might fancy the campaign over now: but it was not. Along the country of the Danube, from the Euxine to the Alps, the Teutons had still the advantage of interior lines, and vast bodies of men—Herules, Gepids, Ostrogoths, Lombards—were coming down in an enormous échellon similar to that which forced the Rhine; to force Italy at the same fatal point—Venetia. The party who could command the last reserve would win, as is the rule. And the last reserves were with our race. They must win. But not yet. They had, in the mean time, taken up a concave line; a great arc running round the whole west of the Mediterranean from Italy, France, Spain, Algeria, as far as Carthage. They could not move forces round that length of coast, as fast as the Romans could move them by sea; and they had no fleets. Although they had conquered the Western Empire, they were in a very dangerous position, and were about to be very nearly ruined.

For you see, the Romans in turn had changed front at more than a right angle. They lay at first north-west and south-east. They lay in Justinian’s time, north and south. Their right was Constantinople; their left Pentapolis; between those two points they held Greece, Asia Minor, Syria and Egypt; a position of wealth incalculable. Meanwhile, as we must remember always, they were masters of the sea, and therefore of the interior lines of operation. They had been forced into this position; but, like Romans, they had accepted it. With the boundless common sense of the race (however fallen, debauched, pedantic), they worked it out, and with terrible effect.

Their right in Constantinople was so strong that they cared nothing for it, though it was the only exposed point. They would defend it by hiring the Barbarians, and when they could not pay them, setting them on to kill down each other; while they quietly drew into Constantinople the boundless crops of Asia, Syria and Egypt.

The strength of Constantinople was infinite—commanding two seas and two continents. It is, as the genius of Constantinople saw—as the genius of the Czar Nicholas saw—the strongest spot, perhaps, in the world. That fact was what enabled Justinian’s Empire to arise again, and enabled Belisarius and Narses to reconquer Africa and Italy. Remember that, and see how strong the Romans were still.

The Teutons meanwhile had changed their front, by conquering the Western Mediterranean, and were becoming weak, because scattered on exterior lines, to their extreme danger.

I cannot exaggerate the danger of that position. It enabled the Romans by rapid movements of their fleets, to reconquer Africa and Italy. It might have enabled them to do much more.

Belisarius, with great wisdom, began by attacking the Vandals at Carthage on the extreme right. They had put themselves into an isolated position, and were destroyed without help. Then he moved on Italy and the Ostrogoths. He was going to force the positions in detail, and drive them back behind the Alps. What he did not finish, Narses did; and the Teutons were actually driven back behind the Alps for some years.

But Narses had to stop at Italy. Even if not recalled, he could have gone no further. The next move should have been on Spain, if he had really had strength in Italy. But to attack Spain from Constantinople, would have been to go too far from home. The Franks would have crost the Pyrenees, and fallen on his flank. The Visigoths, even if beaten, would have been only pushed across the Straits of Gibraltar, to reconquer the Vandal coast of Africa; while to take troops from Italy for any such purpose, would have been to let in the Lombards—who came, let in or not. There were reserves in Germany still, of which Narses knew full well; for he had seen 5000 Lombards, besides Herules, and Huns, and Avars, fight for him at Nuceria, and destroy the Ostrogoths; and he knew well that they could, if they chose, fight against him.

On the other hand, the Roman Empire had no reserves; while the campaign had just come to that point at which he who can bring up the last reserve wins. Ours were so far from being exhausted, that the heaviest of them, the Franks, came into action, stronger than ever, 200 years after.

But the Roman reserves were gone. If Greece, if Asia Minor, if Egypt, had been the holds of a hardy people, the Romans might have done still—Heaven alone knows what. At least, they might have extended their front once more to the line of Carthage, Sicily, Italy.

But the people of Syria and Egypt, were—what they were. No recruits, as far as I know, were drawn from them. Had they been, they would have been face to face with a Frank, or a Lombard, or a Visigoth, much what—not a Sikh, a Rohilla, or a Ghoorka, but a Bengalee proper—would be face to face with an Englishman. One thousand Varangers might have walked from Constantinople to Alexandria without fighting a pitched battle, if they had had only Greeks and Syrians to face.

Thus the Romans were growing weak. If we had lost, so had they. Every wild Teuton who came down to perish, had destroyed a Roman, or more than one, before he died. Each column which the admirable skill and courage of the Romans had destroyed, had weakened them as much, perhaps more, than its destruction weakened the Teutons; and had, by harrying the country, destroyed the Roman’s power of obtaining supplies. Italy and Turkey at last became too poor to be a fighting ground at all.

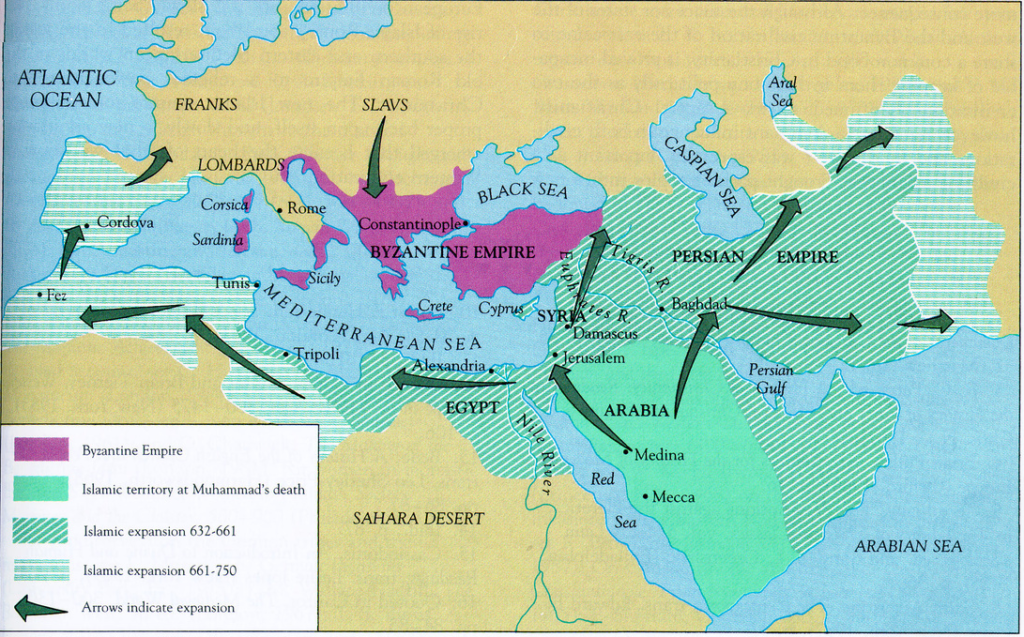

But now comes in one of the strangest new elements in this strange epic—Mohammed and his Arabs.

Suddenly, these Arab tribes, under the excitement of the new Mussulman creed, burst forth of the unknown East. They take the Eastern Empire in the rear; by such a rear attack as the world never saw before or since; they cut it in two; devour it up: and save Europe thereby.

That may seem a strange speech. I must explain it. I have told you how the Eastern Empire and its military position was immensely strong; that Constantinople was a great maritime base of operations, mistress of the Mediterranean. What prevented the Romans from reconquering all the shores of that sea, and establishing themselves in strength in the Morea, or in Sicily, or in Carthage, or in any central base of operations? What forced them to cling to Constantinople, and fight a losing campaign thenceforth. Simply this; the Mussulman had forced their position from the rear, and deprived them of Syria, Egypt, Africa.

But the Teutons could not have opposed them. During the 7th century the Lombards in Italy were lazy and divided; the Goths in Spain lazier and more divided still; the Franks were tearing themselves in pieces by civil war. The years from A.D. 550 to A.D. 750 and the rise of the Carlovingian dynasty, were a period of exhaustion for our race, such as follows on great victories, and the consequent slaughter and collapse.

This was the critical period of the Teutonic race; little talked of, because little known: but very perilous. Nevertheless, whatever the Eastern Empire might have done, the Saracens prevented its doing; and if you hold (with me) that the welfare of the Teutonic race is the welfare of the world; then, meaning nothing less, the Saracen invasion, by crippling the Eastern Empire, saved Europe and our race. And now, gentlemen, was this vast campaign fought without a general? If Trafalgar could not be won without the mind of a Nelson, or Waterloo without the mind of a Wellington, was there no one mind to lead those innumerable armies, on whose success depended the future of the whole human race? Did no one marshal them in that impregnable convex front, from the Euxine to the North Sea? No one guide them to the two great strategic centres, of the Black Forest and Trieste? No one cause them, blind barbarians without maps or science, to follow those rules of war, without which victory in a protracted struggle is impossible; and by the pressure of the Huns behind, force on their flagging myriads to an enterprise which their simplicity fancied at first beyond the powers of mortal men? Believe it who will: but I cannot. I may be told that they gravitated into their places, as stones and mud do. Be it so. They obeyed natural laws of course, as all things do on earth, when they obeyed the laws of war: those too are natural laws, explicable on simple mathematical principles. But while I believe that not a stone or a handful of mud gravitates into its place without the will of God; that it was ordained, ages since, into what particular spot each grain of gold should be washed down from an Australian quartz reef, that a certain man might find it at a certain moment and crisis of his life;—if I be superstitious enough (as thank God I am) to hold that creed, shall I not believe that though this great war had no general upon earth, it may have had a general in Heaven? and that in spite of all their sins, the hosts of our forefathers were the hosts of God?