Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Historical Tales and Legends of the Highlands, compiled by Alexander MacKenzie (published 1878). All spelling in the original.

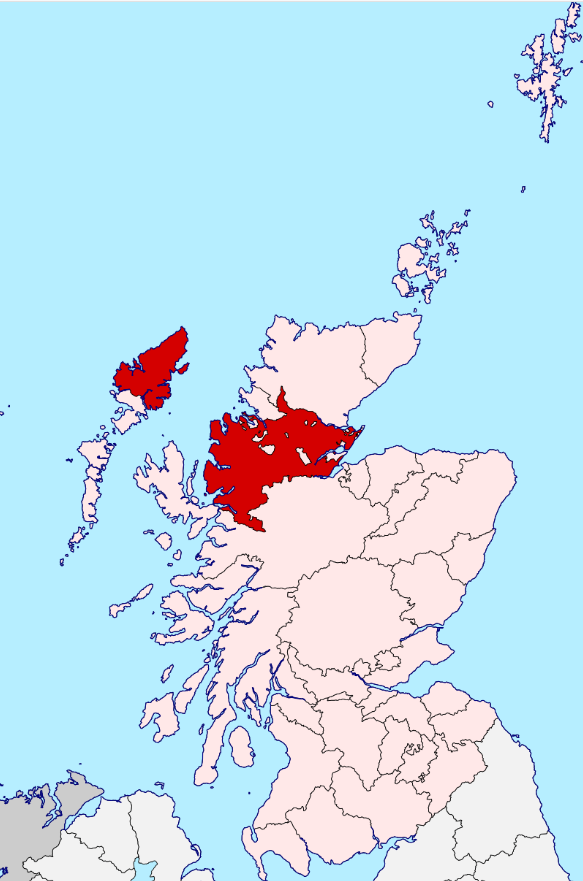

The ancient Chapel of Cilliechriost, in the parish of Urray, in Ross-shire, was the scene of one of the bloodiest acts of ferocity and revenge that history has recorded. The original building has long since disappeared, but the lonely and beautifully situated burying-ground is still in use. The tragedy originated in the many quarrels which arose between two great chiefs of the North Highlands—Mackenzie of Kintail and Macdonell of Glengarry. As usual, the dispute was regarding land, but it is difficult to arrive at the degree of blame to which each party was entitled; enough that there was bad blood between these two paladins of the North. Of course, the quarrel was not allowed to go to sleep for lack of action on the part of their friends and clansmen. The Macdonells having made several raids on the Mackenzie country, the Mackenzies retaliated by the spoiling of Morar with a large, overwhelming force. The Macdonells, taking advantage of Kenneth Mackenzie’s visit to Mull with the view to influence Maclean to induce the former to peace, once more committed great devastation in the Mackenzie country, under the leadership of Glengarry’s son, Angus. From Kintail and Lochalsh the clan Mackenzie gathered fast, but too late to prevent Macdonell from escaping to sea with his boats loaded with the foray. A portion of the Mackenzies ran to Eileandonan, while another portion sped to the narrow strait of the Kyle between Skye and the mainland, through which the Macdonells, on their return, of necessity must pass. At Eileandonan Lady Mackenzie furnished them with two boats, one ten-oared and one four-oared, also with arrows and ammunition. Though without their chief, the MacKenzies sallied forth, and rowing towards Kyleakin, lay in wait for the approach of the Macdonells. The first of the Glengarry boats they allowed to pass unchallenged, but the second, which was the thirty-two-oared galley of the chief, was furiously attacked. The unprepared Macdonells, rushing to the side of the heavily loaded boat, swamped the craft, and were all thrown into the sea, where they were dispatched in large numbers, and those who escaped to the land were destroyed “by the Kintail men, who killed them like sealchies.”

Time passed on, Donald Gruamach, the old chief, died ere he could mature matters for adequate retaliation of the Kyle tragedy and the loss of his son Angus. The chief of the clan was an infant in whom the feelings of revenge could not be worked out by action; but there was one, his cousin, who was the captain or leader, in whom the bitterest thoughts exercised their fullest sway. It seems now impossible that such acts could have occurred, and it gives one a startling idea of the state of the country, when such a terrible instance of private vengeance could have been carried out so recently as the beginning of the seventeenth century, without any notice being taken of it, even in those days of general blood and rapine. Notwithstanding the hideousness of sacrilege and murder, which in magnitude of atrocity was scarcely ever equalled, there are many living, even in the immediate neighbourhood, who are ignorant of the cause of the act.

Macranuil of Lundi, captain of the clan, whose personal prowess was only equalled by his intense ferocity, made many incursions into the Mackenzie country, sweeping away their cattle and otherwise doing them serious injury; but these were but preludes to that sanguinary act on which his soul gloated, and by which he hoped effectually to avenge the loss of influence and property of which his clan was deprived by the Mackenzies, and more particularly to wash out the records of the death of his chief and clansman at Kyleakin. In order to form his plans more effectually, he wandered for some time as a mendicant among the Mackenzies, in order the more successfully to fix on the best means and place for his revenge. A solitary life offered up to expiate the manes of his relatives was not sufficient in his estimation, but the life’s blood of such a number of his bitterest foemen, and an act at which the country should stand aghast was absolutely necessary.

Returning home, he gathered together a number of the most desperate of his clan, and by a forced march across the hills arrived at the Church of Cilliechriost on a Sunday forenoon, when it was filled by a crowd of worshippers of the clan Mackenzie. Without a moment’s delay, without a single pang of remorse, and while the song of praise ascended to heaven from fathers, mothers, and children, he surrounded the church with his band, and with lighted torches set fire to the roof. The building was thatched, and while a gentle breeze from the east fanned the fire, the song of praise mingled with the crackling of the flames, until the imprisoned congregation, becoming conscious of their situation, rushed to the doors and windows, where they were met by a double row of bristling swords. Now, indeed, arose the wild wail of despair, the shrieks of women, the infuriated cries of men, and the helpless screaming of children; these mingled with the roaring of the flames appalled even the Macdonells, but not so Allan Dubh. ‘Thrust them back into the flames,’ cried he, ‘for he that suffers aught to escape alive from Cilliechriost shall be branded as a traitor to his clan;’ and they were thrust back or mercilessly hewn down within the narrow porch, until the dead bodies, piled upon each other, opposed an unsurmountable barrier to the living. Anxious for the preservation of their young children, the scorching mothers threw them from the windows in the vain hope that the feelings of parents awakened in the breasts of the Macdonells would induce them to spare them, but not so. At the command of Allan of Lundi they were received on the points of the broadswords of men in whose breasts mercy had no place. It was a wild and fearful sight, only witnessed by a wild and fearful race. During the tragedy they listened with delight to the piper of the band, who, marching round the burning pile, played, to drown the screams of the victims, an extempore pibroch, which has ever since been distinguished as the war tune of Glengarry, under the title of ‘Cilliechriost.’ The flaming roof fell upon the burning victims; soon the screams ceased to be heard, a column of smoke and flame leapt into the air, the pibroch ceased, the last smothering groan of existence ascended into the still sky of that Sabbath morning, whispering as it died away that the agonies of the congregation were over.

East, west, north, and south looked Allan Dubh Macranuil. Not a living soul met his eye. The fire he kindled had destroyed, like the spirit of desolation. Not a sound met his ear, and his own tiger soul sunk within him in dismay. The parish of Cilliechriost seemed swept of every living thing. The fearful silence that prevailed, in a quarter lately so thickly peopled, struck his followers with dread: for they had given in one hour the inhabitants of a whole parish one terrible grave. The desert which they had created filled them with dismay, heightened into terror by the howls of the masterless sheep dogs, and they turned to fly. Worn out with the suddenness of their long march from Glengarry, and with their late fiendish exertions, on their return they sat down to rest on the green face of Glenconvinth, which route they took in order to reach Lundi through the centre of Glenmoriston by Urquhart. Before they fled from Cilliechriost, Allan divided his party into two, one passing by Inverness and the other as already mentioned.

The Macdonells, however, were not allowed to escape, for the terrible deed had roused the Mackenzies as effectually as if the fiery cross had been sent through their territories. A youthful leader, a cadet of the family of Seaforth, in an incredibly short time, found himself surrounded by a determined band of Mackenzies eager for the fray; these were also divided into two bodies, one commanded by Murdoch Mackenzie of Redcastle, proceeded by Inverness, to follow the pursuit along the southern side of Loch-Ness. Another, headed by Alexander Mackenzie of Coul, struck across the country from Beauly, to follow the party of the Macdonells who fled along the northern side of Loch-Ness under their leader Allan Dubh Macranuil.

The party that fled by Inverness were surprised by Redcastle in a public-house at Torbreck, three miles to the west of the town, where they stopped to refresh themselves. The house was set on fire, and they all—thirty-seven in number—suffered the death which, in the earlier part of the day, they had so wantonly inflicted.

The Mackenzies, under Coul, after a few hours hard running, came up with the Macdonells as they sought a brief repose on the hills towards the burn of Aultsigh. There the Macdonells maintained an unequal conflict; but as guilt only brings faint hearts to its unfortunate votaries, they turned and again fled precipitately to the burn. Many, however, missed the ford, and the channel being rough and rocky several fell under the swords of the victorious Mackenzies. The remainder, with all the speed they could make, held on for miles, lighted by a splendid and cloudless moon, and when the rays of the morning burst upon them, Allan Dubh Macranuil and his party were seen ascending the southern ridge of Glen-Urquhart, with the Mackenzies close in their rear. Allan, casting an eye behind him and observing the superior numbers and determination of his pursuers, called upon his band to disperse, in order to confuse his pursuers, and so divert the chase from himself. This being done, he again set forward at the height of his speed, and after a long run, drew breath to reconnoitre, when, to his dismay, he found that the avenging Mackenzies were still on his track in one unbroken mass. Again he divided his men and bent his flight towards the shore of Loch-Ness, but still he saw the foe bearing down upon him with redoubled vigour. Becoming fearfully alive to his position, he cried to his few remaining companions again to disperse, until they left him, one by one, and he was alone. Allan, who as a mark of superiority and as Captain of the Glengarry Macdonells, always wore a red jacket, was thus easily distinguished from the rest of his clansmen, and the Mackenzies, being anxious for his capture, easily singled him out as the object of their joint and undivided pursuit. Perceiving the sword of vengeance ready to descend on his head, he took a resolution as desperate in its conception as it was unequalled in its accomplishment. Taking a short course towards the fearful ravine of Aultsigh, he divested himself of his plaid and buckler, and turning to the leader of the Mackenzies, who had nearly come up to him, beckoned him to follow, then, with a few yards of a run, he sprang over the yawning chasm, never before contemplated without a shudder. The agitation of his mind at the moment completely overshadowed the danger of the attempt, and being of an athletic frame, he succeeded in clearing the desperate leap. The young and reckless Mackenzie, full of ardour and determined at all hazards to capture the murderer, followed; but, being a stranger to the real width of the chasm, perhaps of less nerve than his adversary, and certainly not stimulated with the same feelings, he only touched the opposite brink with his toes, and slipping downwards, he clung by a slender shoot of hazel which grew over the tremendous abyss. Allan Dubh, looking round on his pursuer and observing the agitation of the hazel bush, immediately guessed the cause, and returning with the ferocity of a demon who had succeeded in getting his victim into his fangs, hoarsely whispered, ‘I have given much to your race this day, I shall give them this also; surely now the debt is paid;’ then cutting the hazel twig with his sword, the intrepid youth was dashed from crag to crag until he reached the stream below, a bloody and misshapen mass.

Macranuil again commenced his flight, but one of the Mackenzies, who by this time had come up, sent a musket shot after him, by which he was wounded, and obliged to slacken his pace. None of his pursuers, however, on coming up to Aultsigh, dared or dreamt of taking a leap which had been so fatal to their youthful leader, and were therefore under the necessity of taking a circuitous route to gain the other side. This circumstance enabled Macranuil to increase the distance between him and his pursuers, but the loss of blood, occasioned by his wound, so weakened him that very soon he found his determined enemies were fast gaining on him. Like an infuriated wolf he hesitated whether to await the undivided attack of the Mackenzies or plunge into Loch-Ness and attempt to swim across its waters. The shouts of his approaching enemies soon decided him, and he sprung into its deep and dark wave. Refreshed by its invigorating coolness he soon swam beyond the reach of their muskets; but in his weak and wounded state it is more than probable he would have sunk ere he had crossed half the breadth had not the firing and the shouts of his enemies proved the means of saving his life. Fraser of Foyers seeing a numerous band of armed men standing on the opposite bank of Loch-Ness, and observing a single swimmer struggling in the water, ordered his boat to be launched, and pulling hard to the individual, discovered him to be his friend Allan Dubh, with whose family Fraser was on terms of friendship. Macranuil, thus rescued, remained at the house of Foyers until he was cured of his wound. The influence and the Clan of the Macdonells subsequently declined, while that of the Mackenzies surely and steadily increased.

The heavy ridge between the vale of Urquhart and Aultsigh, where Allan Dubh Macranuil so often divided his men, is to this day called Monadh-an-leumanaich, or ‘the Moor of the Leaper.’

5

[…] (Men of the West): The ancient Chapel of Cilliechriost, in the parish of Urray, in Ross-shire, was the scene of one […]