Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Navies in Exile, by A. D. Divine (published 1944).

The Dutch Navy at the outbreak of war was small, but it had a very considerable proportion of modern ships. It was on the verge of significant expansion. The rising temperature of the Far East had led the Dutch Admiralty, and finally the Dutch Government, into plans for a substantial increase both in personnel and in ships. Broadly speaking, the new navy was planned not for war in Europe but in the seas around the rich island Empire of the Netherlands in the East.

In Europe Holland had a tradition of neutrality. For a hundred years she had known peace. Even through the Great War of 1914-18 she maintained a rigorous neutrality. Except for the brief skirmishes inherent in colonial empires, her Navy had known nothing of war. There was, far back in history, a great tradition— the names of Tromp and de Ruyter, the names of half a hundred battles, stand high in the roll of fame — but there had been a gap in that tradition, a long gap. Holland had lost belief in the necessity of war. The Peace Conferences of the Hague were in considerable part an expression of that disbelief. She could conceive of war only in the Far East; and the naval expansion which was determined, and which was beginning to be implemented when Germany invaded her frontiers, was only an expression of that conception.

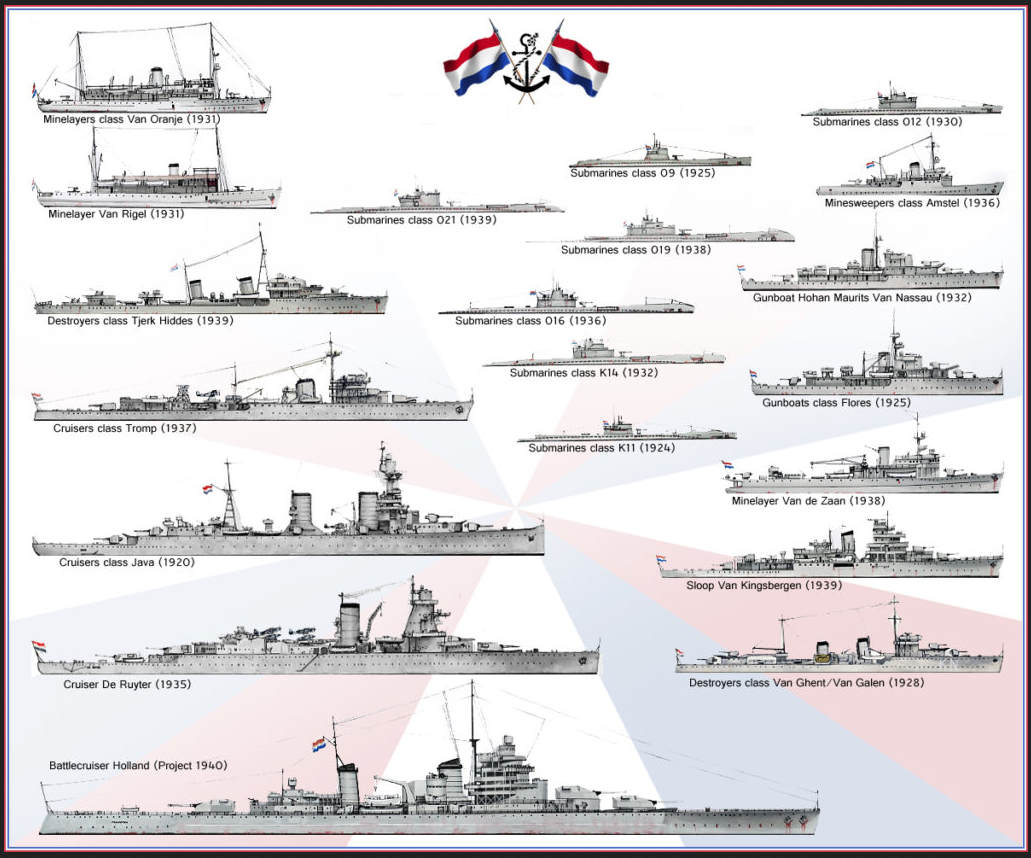

The Navy consisted of five cruisers — Jacob van Heemskerk, Java, De Ruyter, Sumatra and Tromp. There were eight destroyers — Banckert, Evertsen, Jan van Galen, Van Ghent, Piet Hein, Kortenaer, Van Nes and Witte de With — six torpedo-boats, several M.T.B.s, twenty-four submarines, sixteen minesweepers, and some fourteen auxiliary craft of one type and another. It was planned to add to these under the building programme of May, 1940, three battle cruisers of 27,000 tons, two 8,000-ton cruisers, one light cruiser, four destroyers, nineteen M.T.B.s, seven submarines, six escort vessels, seven gunboats, six minesweepers and a force of flying-boats. This was an important programme. Had it been completed in time, the history of the war in the Far East might have been very different. It was not completed.

In May of 1940 the greater portion of the Navy as it then existed was at Surabaya and Batavia and the various naval ports of the East Indian Islands. Of a total complement of 11,750 officers and men in the Service only about 3,000 were in the Netherlands and European waters. Only one cruiser was in Home Waters at the time of the invasion; otherwise there were no ships bigger than destroyers.

Since Germany attacked from the land frontiers, there was little that the Navy could do to stem the assault. Not until the parachute troops landed in the ports and the enemy tried to cross the great dyke of the Zuider Zee did the guns of the Navy play their full part. It is one of the bitterest ironies of this new type of war that Holland’s Navy came into action for the first time after a hundred years of peace in the very heart of its greatest port.

It is curious, in view of the massing of German troops and the enormous land preparations, that the first act of hostility against Holland should have been on the sea.

Shortly after midnight of Thursday, May 9th, coastguards reported considerable air activity over the coastwise channels with intermittent heavy explosions. This pointed undoubtedly to the laying of magnetic mines. Three hours later, in the early morning of Friday, May 10th, the air activity against the land began. At 3.15 a.m. the aerodromes of Schiphol, Waalhaven, Bergen and De Kooy were bombed. Germany was at war with Holland. Unprovoked, treacherous, brutal, her great attack was launched with all the odious insincerities of German policy.

Holland’s military power was considerable, but it was insufficient to cover the whole long eastern frontier against the enormous weight of a German armoured onslaught. The terrain, because of the lack of natural obstacles, does not permit of the formation of any defensive line from the Ems to Aix-la-Chapelle. It had been decided, therefore, to organise a defensive in three stages, sacrificing the northern provinces to the harsh necessity of war. The first line, that of the Yssel, ran from the eastern end of the Zuider Zee along the River Yssel. It was intended as a delaying line only, as a protection against strategic surprise. Its troops were to fall back on the main forces which held the Grebbe line, the second and principal line of defence. This line ran from the southern end of the Zuider Zee to the Rhine (here called the Waal) and then in a southerly direction to the Belgian frontier, where it linked up with the line of the Albert Canal. If this line were broken (and though shorter than the other, it was still very long), there remained a third barrier — the barrier that lay between the Zuider Zee and the great arm of the Hollandsche Diep, the estuary of the Rhine. This was the line that with its inundations, with the Zuider Zee, with the estuary, was to make an island — and an island fortress — of the province of Holland itself.

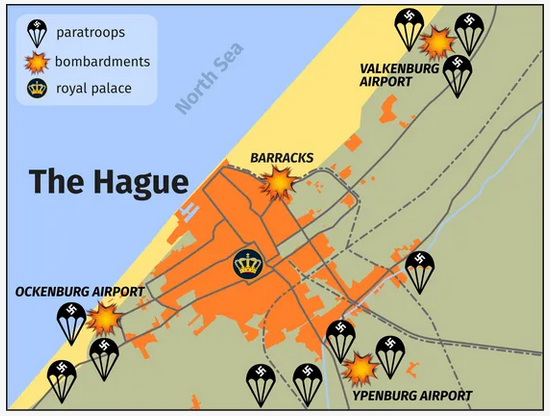

This is not the place to discuss the military campaign. In swift and whirlwind moves, while the Dutch Army fought with a gallantry that excited the admiration of the world, Germany drove through the outer defences. Treachery and surprise breached the fortress. The Moerdijk bridge (communicating across the estuary of the Rhine) was captured by enemy troops in Dutch uniforms before it could be destroyed. Enormous numbers of parachute troops were dropped inside the fortress island. The Queen herself was in danger. And the Dutch strategy, which had depended on the reinforcements of the First Army Corps (which had been intended to man the Holland line when the Grebbe line was breached) broke down, for the First Army Corps had to be split into fragments to deal with parachutists at Rotterdam, at the Hague, at Delft and a dozen other places. Meanwhile Germany was attacking in the north as well, and had captured the eastern end of the new dyke across the mouth of the Zuider Zee.

In the terrible confusion of disaster, with the whole strategic plan in fragments almost in the hour of its inception, with the enemy everywhere — not merely in the outer line of the encirclements, but in the inner defences — the Navy came in to play its part.

There have been few engagements in this war so fantastic as the fight of the gunboat Freyr. It began at Arnhem. Arnhem is in Gelderland, almost on the German frontier, the very heart of inland Holland — yet here, on the Lek, a branch of the River Rhine, she opened fire in support of the left flank of the Dutch troops as they fell back before the mad weight of Germany. From Arnhem to Rhenen she fought magnificently. The Grebbe line went, and she fell back by Wijk and Kuilenburg to Vreeswijk. She kept on fighting until she had to be sunk by her own crew after Holland had capitulated.

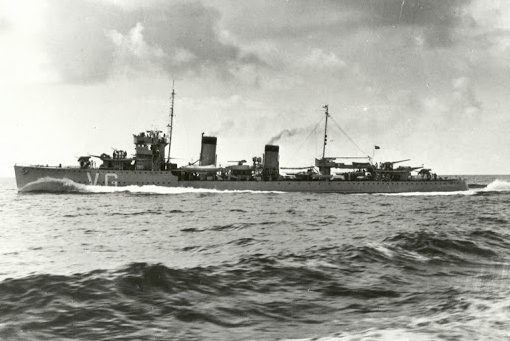

Meanwhile the first German attempt to take the Hague and the person of the Queen was broken under the determination of the Dutch police and the local garrisons. Late in the afternoon the Germans made a tremendous effort to reinforce the parachute battalions. Transport planes came down on the beach south of Katwijk at low tide. The destroyer van Galen, racing up to Rotterdam to help, coincided with the landings, and her shell-fire destroyed plane after plane. This second attempt was broken.

But simultaneously with the attack on the Hague the Germans had occupied the Waalhaven aerodrome. The bombing in the small hours had disorganised the defences; a swift parachute attack occupied it; and that attack was followed by brilliantly organised troop-carrier landings. Waalhaven is the great commercial harbour of Rotterdam. It lies to the south-west of the city on the Nieuwe Maas. The aerodrome is to the east of it. Fanning out from the flying-ground the German troops occupied Waalhaven itself and the south bank of the Maas, and began to infiltrate into the city to attack the river crossings in conjunction with other parachute troops dropped near them and with troops landed from amphibian planes on the Maas itself.

Into that struggle raced, impetuous, the torpedo-boat H.M.Z.5 and the torpedo motor boat 51. With the help of marines from the Rotterdam establishment and covered by fire from the little ships, the bridges were recaptured and held for a while.

It was obvious, however, that heavier metal was needed against the reinforcements that were pouring in from the Waalhaven aerodrome. The van Galen was at Den Helder at the north tip of Holland, holding a watching brief against a German sea attack. She came racing down, and on the way played her part at the battle of the Hague. From there she turned up the Nieuwe Waterweg, already made intolerably treacherous with magnetic mines, and, somehow threading her way through the unseen dangers, reached the port. There on the narrow water she came into action again — an action that played an important part in stemming the first rush of the Germans.

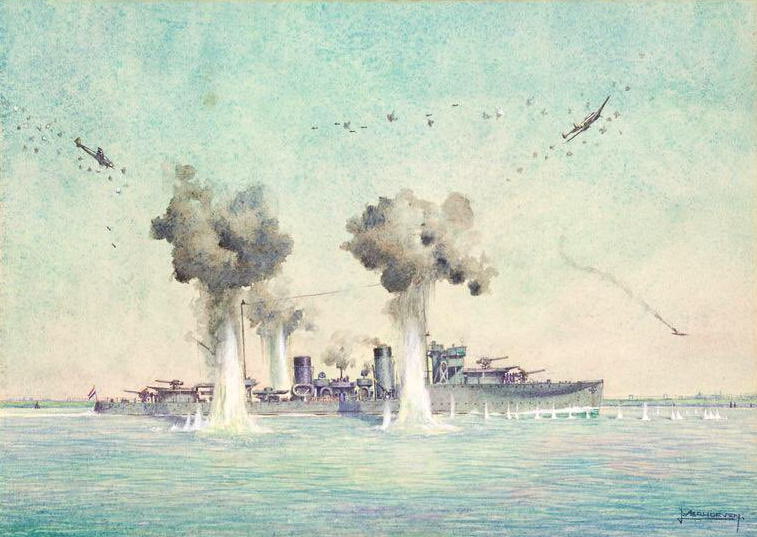

Her guns shelled the aerodrome and the concentrations of troops, and inflicted heavy casualties. But she herself was like a rat in a trap — a trap made of narrow channels, of harbour basins, of small connecting canals. She had no room in which to manoeuvre, no place in which to work up to full speed against the threat of bombs or artillery fire. She moved violently from place to place — and always the bombs sought her out. Thirty-one dive bombing attacks were made on her. Again and again she dodged bombs that fell with shattering violence in the shallow water beside her. All the while she continued to work her guns until at last in the Merwede Haven she received a direct hit and had to be abandoned in a sinking condition.

Her crew went ashore and made of themselves an army, they fought valiantly against the weight of the German forces on the South bank. But the Nieuwe Waterweg had become too dangerous, and the commander of the van Galen reported that it was impossible for the Johan Maurits van Nassau, a gunboat which had been ordered to join him, to operate there. The same considerations applied to the British destroyers which were coming in to help.

Meanwhile from the north the German attack was swinging in. At Delfzijl the Dutch forces had demolished the harbour, blocked the locks, and retired towards the Zuiderzeedyke. In the late afternoon of May 10th they made contact with the forces which had fought a delaying action in Groningen and Friesland, crossed the dyke in the night of May 10th, and took up a defensive position near Den Helder. On the following day the Germans attacked the eastern bridge-head of the dyke. The German Air Force, free of opposition, attacked the fortifications of the dyke, and under their cover the Germans broke through and seized the dyke as far as Kornwerderzand. Meanwhile the Johan Maurits van Nassau had raced round from the Hook of Holland. She anchored herself in the open water of the Wadden Zee and began an astonishing bombardment of the Germans. In the course of this she silenced the German battery on the eastern bridge-head from a distance of eighteen kilometres. The ranging was done from the fortified position on Kornwerderzand, whence it was telephoned to Den Helder whence it was passed by wireless to the Nassau. Despite that complicated connection the fire was brilliant, and owing to the thickness of the weather the Germans never discovered the gunboat.

Unable to break across the dyke against this gallant holding, the Germans captured the eastern coastline of the Zuider Zee, seized all the small craft they could, brought others overland, and planned an invasion across the water. There were no troops available to man the western coast of the Zuider Zee.

To meet this new and critical situation the Navy was flung in again. One torpedo-boat, three gunboats and two minesweepers came in to reinforce the old river gunboat that was the “heavy metal” of the tiny motor-boat force established there. On the urgent request of the Dutch Admiralty they were reinforced by British motor torpedo-boats, which came in by the North Sea canal through Amsterdam. This reinforcement reached there on the night of May 12th.

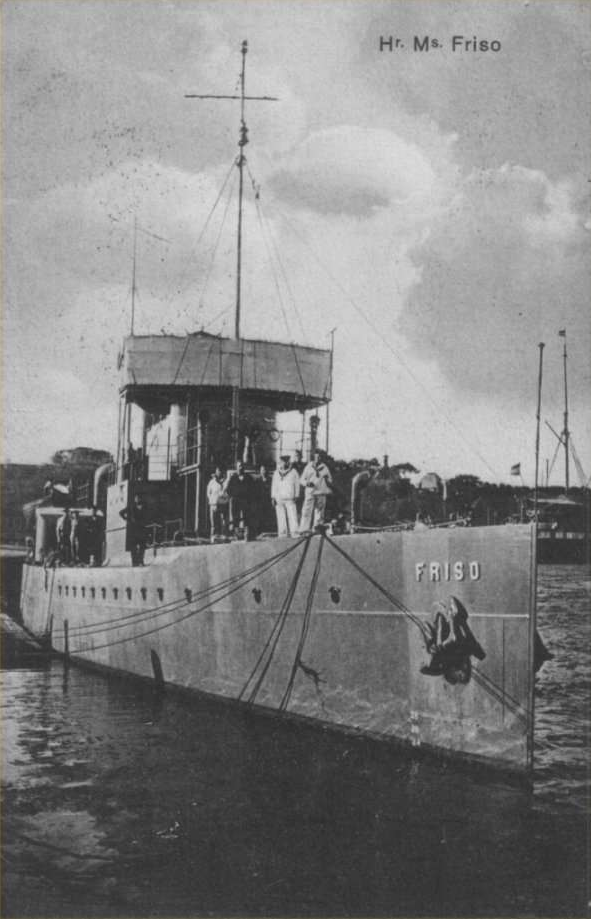

Before they came the tiny Dutch flotillas had rushed the harbour of Stavoren, damaged the invasion forces there, and attacked a dozen other points along the coast. They had no air protection and they suffered heavily. The gunboats H.M. Friso and H.M. Brinio were sunk. They died fighting.

Meanwhile along the main coasts where the Germans were still attempting to use the beaches as landing grounds, patrols of torpedo-boats and gunboats kept the enemy desperately at bay.

But all their work was vain. The speed of the German attack, the ruthless genius with which the parachute troops were used, the combination of treachery from without and from within, breached the fortress Holland. From the south the German force, striking up, broke resistance. The possible line of retirement of the Holland garrison was lost. It became obvious that, except for the islands to the south, resistance would have to be abandoned.

It was early apparent that a major portion of the German plan was the capture of the person of the Queen and of the Dutch Government itself. It became urgently necessary, with the parachutists floating down through the Spring skies, for the Queen to move to a safer area. The crew of the British destroyer which took Her Majesty from Holland speak still of the unhurried dignity of that very great lady. The first plan was that she should move towards the south, but even as the departure began the new era was attacked. The destroyer headed out for the coast of England. In the evening of the same day another ship brought the Dutch Government to Britain. And in the same hours began the movement of the Navy — such of its units, that is, as could take no part in the fighting.

That was an astonishing evacuation. The Germans had attempted to block every port in Holland with magnetic mines — Flushing, the Waterweg, Ymuiden. Two ships leaving Rotterdam, one of them a British vessel carrying refugees, blew up and dangerously obstructed the channel. The desperate work of British magnetic minesweepers could not clear the ports in time. At Ymuiden the S.S. van Renselaer struck a magnetic mine just outside the locks, while the minesweeper M III was blown up on the other side. Warships building and awaiting completion in Rotterdam were blocked in the port, and when the decision to surrender Holland was made, they were blown up.

On the evening of the 13th, however, two new submarines O 23 and O 24, sufficiently complete to face the open sea, slipped out through the mass of the magnetic mines and got away. One of them had made a couple of trial runs but had never dived. The Germans were already in Rotterdam, and there were only fifteen men aboard this submarine, including a harbour official. The position was desperate, and her commander decided to make the at tempt. As she edged away from the quay a number of her crew arrived and made flying leaps on to the deck.

She got out through the Nieuwe Waterweg and the outside channels and reached the open sea, and as she did so German planes came swooping out of the cloud to the attack. She had no deck armament to withstand them; her only hope of safety was in diving. She had never dived before, and she had barely enough crew to man the controls. Her commander, however, had no alternative. He gave the order to dive believing that he was signing his own death-warrant. She dived and escaped.

For hours she lay on the sea bottom. Lying there, the commander made the rounds of his ship. Heavy condensation had set in, and he found the dockyard official sitting placidly with an umbrella over his head. At one time it seemed doubtful if they would be able to surface again, but they got her up and found bombers once more over their heads. This time they were British, and, thrusting across the shallows of the North Sea, they got safely to an English port.

A gunboat lying in the Scheldt in Zeeland had just completed three years’ duty in the Netherlands East Indies. Her crew were on leave, but they came back to play their part, and in the end she too was ordered to make her escape. The channel itself was full of magnetic mines, and she was not degaussed. There was a desperate chance if she steamed through the shallows at high tide, close to the banks. Along these shallows there were wooden groins made of stout piling. Her commander took her through and over these. Even today, after two years of working about the British coast, her bottom shows the scars of that mad, hairbreadth race to safety.

They saved, too, the College of Den Helder, not the equipment, not even many of the staff, but the one vital thing that is a naval college — the cadets. Already these boys in their teens had established a fighting record. Three of them had taken ammunition supplies across the shell-swept Zuiderzeedyke to beleaguered Kornwerderzand; fifteen of them had helped to bring nine hundred parachutist prisoners across to England; four of them, with a lieutenant in charge, brought across the almost sacred Vaandel, the standard of the Corps — the only standard that was to escape from all Holland in that terrible time.

Seventy-nine of them reached England safely, and with these the instructors who had escaped set up their College of Den Helder in the West Country. They began it with blackboards that had been used for deck games in the lounge of a Dutch passenger vessel lying in the harbour; they continued it ashore in a great estate. Out of farm buildings they made seamanship demonstration rooms, armourers’ equipment rooms. Out of the pig-sty in the centre they made a demonstration gun-site. A score of these boys went out to the East Indies, and a new college was begun at Surabaya. And to them a replica of the Vaandel was sent — the guarantee of the continuity of the Royal Navy of the Netherlands.

Meanwhile from other ports the surviving units of the Dutch Navy, one by one, made their escape. The half-finished destroyer Isaac Sweers was towed across, so was other new construction. Gunboats and boats that had survived the attacks of bombers got across under their own power, but even that withdrawal was at tended with loss. The gunboat Johan Maurits van Nassau, fresh from stemming the German advance across the Zuiderzeedyke, was attacked by dive-bombers and lost.

The fight for Holland was over. There remained the last days of resistance in the south. All that a fighting force could do the Dutch Navy had done. They had held the northern arm of the German pincer; they had defied the tip of the southern arm in Rotterdam itself; they had fought between the narrow banks of rivers, on the edges of canals, in the basins of the harbours; they had fought on land. They had lost everything save honour — but they had added to the great roll of the Navy of the Netherlands.