Editor’s note: The following article by S.Sgt. Bob Speer is extracted from Brief, a magazine published for Army Air Force personnel serving in the Pacific Theater (July 24, 1945).

No one will ever really know. Only T.Sgt. Guillermo Abrego could tell the full story of what is one of the strangest single exploits of the war, because only his senses felt it, only his eyes were there to witness, only his brains and will and guts provided the motive power on the loneliest flight since Lindbergh’s. And Guillermo Abrego is dead. The 23-year-old flight engineer, by one of those casual ironies of war, was killed at the very threshold of success, within inches and seconds of safety, after going through hell to get there. Abrego almost brought it off. But even in failure, his was a great try. Here is what he did:

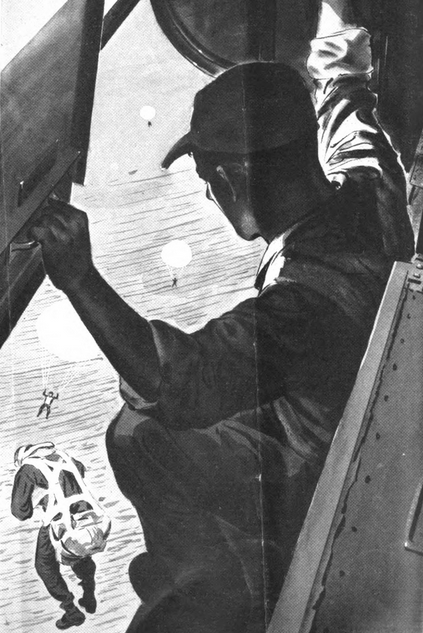

Standing on the catwalk of a crippled B-24, 200 miles out of Marcus and 600 miles from base, Guillermo Abrego for his own private reasons made a decision. As he stood there watching his crewmates plummet out of the hatches, their white chutes drifting down and away, he decided to disobey the pilot’s command to jump. He tricked the pilot into jumping without him. Then Abrego grabbed the controls. The plane was a flying sieve, with four direct hits in her wings and belly. Her Number 3 engine was out and her Number 4 was nearly useless, with precious gasoline leaking out in streams. Her hydraulic system was gone. Her landing gear was shot up, she had lost hundreds of gallons of fuel and her Number 1 engine was overheated and ready to go.

But somehow – no one will ever really know how – Abrego kept her going. He headed the broken bomber into thickening dusk and pushed her along, carefully. He did his own piloting. He did his own navigating. He nursed and lifted and prayed the plane hour after hour for 600 long miles over an empty ocean, plugging along through the night, coaxing the stripped, complaining ship back home. Nearly six lonely hours later, he came at last to Tinian and set her down. And there Abrego’s luck ran out. The battered Liberator lurched on her flat tire while he fought for control. She veered sharply. Abrego tried to take her up for another attempt. She climbed her last 30 feet, stalled out and went in.

Navy men at the Tinian field ran out in an attempt to save the crew. They broke into her hulk and swarmed inside. There was nothing but emptiness and silence except for the wind through the flak holes in her broken belly and the popping and crackling as her engines cooled. They stared at each other and felt shivers down their backs. “It’s a goddam ghost ship,” one whispered. “She came in by herself; she was trying to come home.” Minutes later, and outside the cockpit, they found Abrego at last, but nothing could be done. He never gained consciousness. He never muttered so much as a word that the hospital attendants could make out, and six hours later he died.

It was Abrego’s story – no one knew it but himself – and he was dead. And nobody found out any more about it for two more weeks, when the rest of the crew landed after a miraculous rescue by submarine. Then the pilot, Lt. Floyd Beanblossom of Los Angeles, filled in some of the holes.

“Abrego was one of my best friends,” he said. “And he was the best flight engineer in the Marianas. He knew everything there was to know about a Liberator; he was the kind of guy who spent all his spare time reading tech orders when everybody else was playing cards or horsing around. He was a big, dark, handsome kid, of Spanish extraction, with a wife and baby back home in Enid, Okla. A very pleasant guy to have around. Went straight into the Army at 19 , and had been in for four years, during which time he’d been an old line chief back at Liberal, Kan., for a long while. He’d piled up more than 1,200 hours in B-24’s – he worshiped the damn plane, and talked and ate and slept airplanes and engineering. He was interested in everything on a B-24, and couldn’t rest until he’d mastered it. I’m an old Liberator instructor and he was always pestering me to show him the ropes. Like most flight engineers, Abrego had piled up a lot of stick time over the years, knew how to use the auto pilot, fly a heading, work a radio compass, and somewhere along the line he had even talked somebody into letting him shoot landings, which he could make fairly decently. He was as good a flight engineer as it was possible to be. When we got over here in April, Abrego organized classes for the crew chiefs and even the best of ’em admitted he could teach ’em plenty. But not even Abrego could teach ’em how to combat a jinx.

“Because we were a jinxed ship from the start. On our first mission, we took a direct flak hit over Marcus and our co-pilot, Lt. Roy Grice of Oakdale, Tenn., lost a leg. Our second mission was uneventful, but on our third strike we were hit again over Marcus, fortunately not bad. The next mission made it three out of four and won the big cigar for the Marcus ack-ack gunners, who are far and away the best flak experts in the Pacific. We got it but good.”

Wincing in agreement, Lt. Joseph Arena of Boston, bombardier, broke into the conversation. “We were on the bomb run when they nailed us,” he said. “The Japs threw up about 20 bursts and scored hits on nine of the 11 planes in our formation, so you can see what kind of shooting the little men are putting out. We had four direct hits, the first one on our Number 3 engine, knocking it out and puncturing our right wheel. Another one burst right under our nose. A third shell smacked our open bomb bays and the flak made a hell of a clang as it glanced off the bombs. The fourth burst got us beneath the tail. Almost simultaneously we got our bombs away and headed for home, but all of us knew in our hearts we were through.”

The B-24 was dropping 500 feet a minute while her bad engine smoked and ran away, wind-milling furiously. Beanblossom and Abrego worked to feather the prop, but the mechanism had been shot off. Eventually the prop froze when the oil gave out, but its blades were flat against the wind and caused heavy drag. The crew tried to lighten the ship. Out went the empty bomb bay gas tank, the ball turret, guns and ammunition, part of upper turret, waist windows, everything that could be unscrewed or ripped loose. And after 20 minutes, with the plane stripped down to a rattling shell, Beanblossom managed to hold his altitude at 3,800 feet, with the help of Lt. Robert Davis, squadron operations officer who had gone along as co-pilot.

“We’d been hit about 4 p.m. and we managed to plug along for an hour and a half,” Beanblossom went on. “We kept going only by using full flaps and throttling down to 125 miles an hour, just above stalling speed. The Number 4 was giving hardly any power, and the Number 1 was overheated and getting ready to cut out. All the time, Abrego was working like crazy to hold her aloft. Somehow he managed to transfer gas from the dead engine and salvaged a lot of it, but the Number 4 was still leaking badly. We had a big consultation to figure our chances. As close as we could estimate, we had just enough gas to keep us going three hours and 1o minutes. And it would take a minimum of four hours to make the nearest airfield at Saipan.

“So by simple arithmetic we knew we couldn’t make it and that we’d have to hit the silk somewhere. We had only half an hour of light left and we were still 600 miles from the Marianas. If we waited until the last minute to bail out we’d be a lot closer to Saipan, but it would be pitch dark and no one in the world would ever be able to spot us. On the other hand, if we jumped right now, there would still be light enough for a Navy Dumbo to set down in the water and pick us up. We were in contact through our patched-up radio, with a Dumbo that was coming up fast, and we talked it over with them. They agreed to land for us if we jumped, since the sea was like a pan of milk. Under the circumstances there was only one thing to do. I ordered the crew to get ready to bail out, and meanwhile flew circles to enable the dumbo to catch up to us. Finally we saw him coming and the boys began to jump. I waited until I thought all of them had gone, then set her on automatic pilot and went back to the bomb bay to jump myself. And there I saw Abrego standing on the catwalk, adjusting his chute.

“I told him to jump, but he just looked at me, half-smiling. I gave him a little shove and he pulled away. ‘You don’t have to push me,’ he said. ‘I’ll jump okay – let’s jump together.’ Well, something about his manner made me suspicious, so I looked him in the eye and said, ‘Are you sure, now?’ He stared right back, without flinching, and nodded. So I said, ‘Okay then – here we go, pal,’ and I dropped out. After my pack opened, I counted the chutes drifting down over two miles of sea, and one was missing and then I knew he hadn’t jumped after all. I could only cuss at myself, and then wish him luck and hope he’d make it, but I was dead sure he’d never coax her back.”

The surviving crew members, sitting remembering the moments of the jump, stared at the floor. The navigator, Flight Officer Anthony DiBenedetto of Washingtonville, N.Y., spoke slowly. “Kind of hard to tell just what another man’s motives are,” he said. “But I’ve heard Abrego say a dozen times that he would never bail out over water. He couldn’t swim a stroke and he used to say that you might as well go down with the ship and get it over with fast, as to strangle slow in the water. And he was such a bug on airplanes that he had tremendous confidence in the plane. As long as she was still aloft, he’d stick with her. It was just another B-24 – we’d never even got around to naming her – and she’d had back luck from the start, but he loved that ship. She was his baby. As I look back now, I know he never did intend to jump, because while we were getting ready to bail out, he slipped in to me and asked what was our compass heading back to the Marianas. I didn’t think anything off it at the time, and told him what it was. Even then, he was figuring on taking his chances with the ship.”

With Abrego at the controls, the B-24 headed into the dusk and soon was gone. The other 10 crewmen splashed into the sea one by one, while another B-24 in their formation, which had dropped back to convoy the crippled ship, swung in and dropped two life rafts. But they couldn’t see the men in the water and the rafts fell out of reach. The B-24 circled again and left for home, and then came the most agonizing moment in the whole experience. The Dumbo swept over them to land, missed them in the growing twilight, veered around and came back, only to circle the water more than a mile away. The men were mere dots in the sea. After several futile sweeps, the Dumbo gave up and flew away. The men in the water heard its engines die away in the distance and then the night was on them and they were alone, without life rafts, bobbing in Mae Wests in the open ocean 600 miles from land. They couldn’t even see each other.

“That ended it,” said Beanblossom. “Every man in the crew gave up hope right then. We had flown search missions for three weeks at a stretch, looking for Gen. Harmon. We knew it was simply impossible to spot single men from planes, unless they were in rafts or had sea dye or a mirror. With no dramatics at all, we just made up our minds quietly that we were finished. Our sole chance had been the Dumbo and that had failed. We had used up our luck. All that remained to be seen was how long it would take us to die.”

Long Night

As the night wore on, the men hailed on another and three pairs finally got together. Lt. Beanblossom teamed up with Sgt. Donald Butler of Akron, the tail gunner. DiBenedetto found Cpl. James McDonald of Oak Park, Ill., an unlucky photographer who was not in the crew but had picked that plane to fly the mission in. Lts. Arena and Davis also got together. But four men were alone all night: Sgt. Joe Freiman of Chicago, the instruments man; Sgt. Tom Powers of Richmond, Va., nose gunner; Sgt. William Kluth of Philadelphia, ball gunner, and Sgt. John Barrett of Somerville, Mass., radio operator. These men were in bad shape – about as bad as men can be and still survive – and one of them in fact did not survive.

“Several times during the night, Davis and I hollered to Barrett and he answered,” said Lt. Arena. “I asked him if he had a raft, and he said no. Then he asked me the same thing and I told him no. We were all cussing our luck at not having one-man rafts attached to our chutes like the B-29 crews and fighter pilots have. They were on order, and in fact arrived at the squadron the day after we hit – and there’s some more bad luck for you. But Barrett’s voice was a long way off in the night and we couldn’t get together. After 2 a.m. we tried several times to get some more response from him, but he never said anything more. He had drowned. When we found his body the next day he had been dead about 14 hours. I’ll never forget the sound of his voice across all that dark water when he asked me if we had a raft – not really believing we had, but just asking as a matter of form – so damned lonely and coming from so far away.”

Sgt. Powers, a skinny G.I. who seems the frailest in the crew, put up an almost superhuman demonstration of endurance. His Mae West would not work and finally he threw it away. For 16 hours, with no relief, he treaded water to keep afloat and was still swimming when he was rescued the following afternoon. No one in the Marianas can remember a previous case when a crew has survived more than 20 hours without life rafts – as this crew did – even when its Mae Wests were working. The rescued crewmen say flatly that survival for more than 48 hours in impossible under such circumstances. And no one out here can remember anyone who survived – as powers did – for as long as 16 hours with no Mae West at all.

Powers kept afloat by paddling easily, conserving his strength, and using an emergency survival technique in which he had been briefed. He knotted the ends of his pants legs and swung the pants over his head to fill them with air. The improvised water wings leaked air continually and it was a struggle to keep them filled, but they gave him a sufficient margin of buoyancy to stay afloat. Sgt. Freiman also had trouble with a leaky Mae West which was only partly inflated, but he managed to keep going somehow.

“Those hours dragged on,” said DiBenedetto, the navigator. “Every star seemed a plane, every wave splash sounded like a ship. I’ve never put in such a long night in my life. I was bothered by a small fish about a foot long that kept nibbling at the seat of my pants, but luckily no sharks bothered us, although we saw some next day. It was cold and we had no hope at all and we shivered and shook and our teeth chattered and we tried not to think about the next morning when the sun would get at us.”

The men don’t go into details, but some of them admit that they thought long and seriously of getting it over with, to save themselves suffering. Some looked for a quick end by trying not to struggle, hoping they would drown. But always at the last minute, when they went underwater, the urge to live was overpowering. They found themselves struggling to survive whether they wanted to or not. And finally they settled down grimly to hanging on to the last bitter moment, to sweat it out however long it took.

Sub Plays Safe

“What we didn’t know,” said Lt. Beanblossom, “was that a Navy submarine[1] over 200 miles away had overheard our conversation with Dumbo and had marked our position. And although they had no obligation to help us – and even assumed the Dumbo already had us aboard and on our way home – they decided to come all that way just to play safe and make sure the Dumbo hadn’t missed some of us. That skipper, Commander R. C. Klinker, is a very great guy and for our money there isn’t a better man in the Navy. Mind you, he didn’t have to come. But with no hesitation he turned that sub around and headed full speed for our position. To get to us, he had to come through a restricted zone, putting his ship in great danger. Our planes had instructions to sink any submarine in that area, because none of ours were supposed to be there. But he brought her hundreds of miles, running full speed on the surface. And at noon next day he sighted is, just as a whole flock of Dumbos finally appeared.

“The sub cruised around until she had found us all, scattered over three miles of sea. We were a bad sight, burned raw by the sun, half wacky from thirst, our bodies dehydrated and covered with immersion sores where our clothes had chafed. The last one found was poor Barrett – his body was floating face down. They were getting ready to bring the body aboard for a formal burial at sea, when the currents settled the question. A couple of small waves nudged him gently and he went slowly under. It was just as well, I guess. The sea already had him and a formal burial service would have been a bad ordeal for all of us who were his friends. The men said some prayers as he disappeared. He was a wonderful crewmate and the best radioman I have ever known.”

The nine who survived remained aboard the sub for 12 days and didn’t know what had happened to Abrego until they landed in the Marianas. When they did find out, they couldn’t understand how he had made it back to Tinian. Finally they thought they saw the answer.

Weight Difference

“It was the weight,” said Beanblossom. “The ship was already stripped to her bare bones and we were using 195 gallons of gas an hour, at a speed barely above stalling. I know that when Abrego and I figured the fuel status, we decided that if we’d had an extra 150 gallons of gas, we could have made it back with the full crew. Well, when the 10 men jumped, the plane lost about 2,000 lbs. Abrego probably cut back the power setting to conform to the lighter weight of the ship, and probably saved nearly 50 gallons an hour. He flew for more than five hours after we jumped, arriving at Tinian about 11 o’clock that night. That meant he had saved about 250 gallons of gas over our original schedule, or just enough to make it. And even then, his tanks were bone dry when he hit. The plane did not catch fire although it was demolished – so you know how little gas he must have had.”

There have been hundreds of stories of miraculous escapes by Pacific fliers. There haven’t been so many tales of the men who didn’t quite make it, the ones whose luck was incredible until it deserted them in the stretch. Abrego’s death was one of those. Guts and skill were not enough. Abrego had to have luck as well, and he had it, right up to the moment he needed it most, and then everything went wrong. Abrego’s luck, his will to live, and his faith in his plane kept him going for 600 terrible miles. He did everything right when everything was against him. But in the last crisis – when he had to return to land – his luck ran out.

When Abrego piloted the battered plane over the Tinian coast, he headed for a field with three landing strips. Two of them were long, with no obstructions for hundreds of yards around. Even if he missed those strips, the terrain was flat as a table and he would have survived a crash landing. But he picked the third strip, a short one used mainly for fighters. It was the worst choice he could have made. Then, when the plan lurched on her flat right tire, observers said Abrego still could have survived if he had let her slide. She would have ground looped – but he wouldn’t have been killed. Instead, he tried to take her off again and that was where Lady Luck set her foot down, for the third and last time. The plane stalled and skidded off the runway. There was one pile of coral left from construction, a small heap alone in a big field, with no other obstructions for 200 yards. As if magnetized, the crumpling ship slewed around in a half circle and ran square into the coral heap. Abrego’s trip was over and his luck was gone. Inches short of the finish line, his great and lonely try had failed.

____________________________

[1] USS Sea Fox (SS-402), a Balao class submarine. From Infogalactic: “Two months after commissioning, Sea Fox departed New London for Hawaii and duty in Submarine Division 282 (SubDiv 282). She arrived at Pearl Harbor on 11 September and, on 4 October, got underway on her first war patrol. On 16 October, she entered her initial patrol area near the Bonin Islands, and remained in the Bonin-Volcano Islands area through 25 October, hunting enemy shipping and serving on lifeguard duty for B-24 Liberator strikes against Iwo Jima.”

5