Editor’s note: The following is extracted from The Cavaliers of Fortune: British Heroes in Foreign Wars, by James Grant (published 1858).

Among the many gallant Irishmen, and those descended from the Irish race, who served in the armies of France, and sought there those honours and distinctions which political misfortune and studied misrule denied them at home, I know of none more distinguished, and of none whose name is more worthy of being rescued from oblivion, than General the Count de Lally, the ill-requited leader of the troops of Louis XV in the wars of India.

Arthur Lally was the son of Captain O’Lally, of Tulloch na Daly, in Galway, who passed over to France soon after Limerick capitulated to Goderdt de Ginckel, the Dutch Earl of Athlone, and at the close of that disastrous war in which the Irish troops withstood the army of King William. Captain Lally obtained a commission in the regiment of the Hon. Arthur Dillon, the same battalion in which the great Marshal Macdonald, Duke of Tarentum, commenced his military career as a sub-lieutenant.

Soon after he settled in France, Captain Lally married a French lady of distinction. They had two children, the eldest of whom, Arthur, was soon after his birth enrolled—according to a custom then prevailing in the French army—as a private soldier in the company of his father. In this capacity he served at the famous siege of Barcelona under the Maréchal Duke of Berwick in 1714. His father being an officer of distinguished merit, and his mother being by blood allied to some of the most noble families in France, afforded young Daily every opportunity for the improvement of his mind and person; thus at the age of nineteen he was considered one of the handsomest and most accomplished chevaliers in Paris.

Without having seen much active service, he had then been appointed to a company in that gallant band of exiles whose valour contributed to win many a victory for the House of Bourbon—the Irish Brigade. His regiment—every member of which knew his father’s worth and merit—received him with satisfaction, and his reception took place early in 1718.

In the old French service this was an indispensable ceremony when an officer first joined. His company was drawn up in front of the regiment, with the drummers beating on the flanks. Dressed in full uniform, with his scarf, sword, and gorget, Arthur Lally was led forward by the general of division, who, when the drums ceased, raised his cocked hat, and said:—

“De par le Roi! Soldats, vous reconnoitrez Monsieur de Daily, votre capitaine de la compagnie, et vous lui obeirez en tout ce qu’il vous ordonnera pour le service du Roi, en cette qualité.”

Another ruffle on the drums, the company fell back to its place in the line of the regiment of Dillon, and Arthur Dally was formally installed its captain.

Though he was known by his education and spirit to have possessed all those qualities which were requisite for the perfect soldier, uniting a clear head and solid judgment to a light and joyous, but intrepid heart, he was found to be equally qualified for the civil service of the State; thus at the age of five-and-twenty he was sent by Louis XV to the court of Russia on a political mission of importance. On this duty he acquitted himself ably, his fidelity on one hand securing the confidence of the king his master, by his address and winning manner; on the other, obtaining the esteem and admiration of the Empress Catherine, whose husband, Peter the Great, had died about a year before. On his return to France in 1725 he proceeded to Versailles, where Louis XV, who had then attained his majority, and taken the reins of government from the Regent Duke of Orleans, received him in the most gracious manner, and promoted him to the rank of colonel of infantry; and at the head of his regiment he had the good fortune to acquit himself with distinction wherever he was employed.

He stood high in the favour of the two ministers who succeeded the Duke of Orleans, namely, the Duke de Bourbon and Cardinal Fleury, then in his seventy-third year, a mild and amiable prelate, under whose moderate and conciliatory counsels France enjoyed many years of peace and tranquillity. During service in France, Lally, though somewhat proud and lofty in his manner, succeeded in gaining the esteem and affection of the officers of his regiment, among whom—even in those days of incessant duelling—he was fortunately successful in maintaining the most perfect union and harmony, while by his unalterable firmness subordination was equally maintained.

Thus had passed the time until 1745, when Prince Charles Edward Stuart projected his gallant and unfortunate rising among the clans in the Scottish Highlands. Entering warmly into the design of restoring the hapless House of Stuart, under which his father had served long and faithfully, and with whom he had eaten the bread of exile, Colonel Lally came boldly over to London. While his ostensible object was to recover certain lands in Ireland, to which he averred his father had a claim, his real errand was to serve the young Prince of Scotland, to animate his friends, to excite the malcontents, to promise money, titles, and prepare the Jacobites of South Britain for the tempest that was gathering among the mountains of the north. By his boldness and determination Lally met with the utmost success in London; but being somewhat unwary, his plans and presence were discovered and revealed by a spy to the Duke of Cumberland, who procured immediate orders for his arrest.

Fortunately, however, Lally escaped those shambles to which “the butcher” of the clans had doomed him, and escaping to France about the time Culloden was fought, resumed the command of his regiment.

A war was then waging between France and Britain, and the fleets of the latter had swept those of the former from the ocean. Admiral Hawke had destroyed the French fleet at Belleisle, and in that year upwards of six hundred prizes were taken by our cruisers.

Though the French armies performed some brilliant actions in the Netherlands, where the Marshal-General, Maurice Count de Saxe, defeated and covered with disgrace the troops of the Duke of Cumberland, Louis XV was compelled by naval disasters, and the internal distresses of France, to conclude a peace, a congress for which met at Aix-la-Chapelle in April, 1748; and the definitive treaty was signed in the following October.

During this period, and until his promotion to the rank of lieutenant-general and commander-in-chief in the East Indies, the life of Lally—who had now been created a peer of France—does not present any circumstance or incident worthy of attention. In 1749 he married.

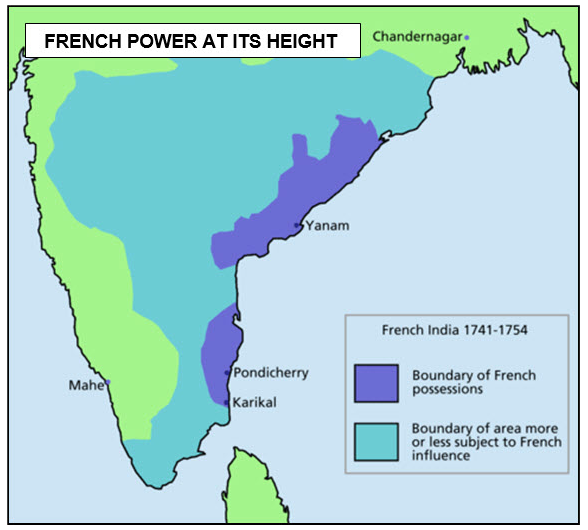

In 1750 a dispute pregnant with hostility ensued between France and Britain respecting their mutual claims in North America; various circumstances which occurred in the East Indies about the same time confirmed the idea that the short peace concluded in 1748 was about to end. Each country prepared for war; but though many unfriendly acts were committed, and bitter recriminations exchanged between the Courts of London and Versailles, until Britain was threatened with invasion, as a curb on her aggressive spirit, hostilities were not formally denounced until the month of June, 1756. The declaration made by George II was mild and moderate in tenor and language, but the declaration promulgated by Louis XV was full of severity and opprobrium. Prussia became the ally of the former; Sweden and Russia joined the latter. In distant regions as well as at home the sanguinary struggle was maintained, and in America France was stripped of all her possessions by the army of the heroic Wolfe.

Immediately after the declaration of war, in the month of August, 1756, the Count de Lally, as Lieutenant-General and Commander-in-Chief of all his Most Christian Majesty’s forces in India, was appointed to conduct an expedition destined for those burning shores, so far distant, and even at that period comparatively so little known to Europeans.

In support of this expedition the Court had destined six millions of livres, six strong battalions of infantry, and three ships of war, which were to co-operate with such an armament as the French India Company could furnish; but the whole of the troops did not embark.

On the 20th February, 1757, the Count de Lally, accompanied by his brother Michael, marched to Brest at the head of two battalions; and though having only two millions of livres in the military chest, embarked on board the ships of the Count d’Aché, who immediately put to sea; but being driven into port again by contrary winds, the squadron was detained until the 2nd of May.

Meanwhile, Major-General the Chevalier des Soupirs, Lally’s second in command, had already reached the Indian Ocean, having departed from L’Orient, the principal port of the India Company, on the 30th of the preceding December, with two battalions and two millions of livres, with which he touched at the Isle of France, without accident.

The general had very ample and important instructions given to him by the India Company. Some of these were to the following effect:—

“The Sieur de Lally is authorized to destroy the fortifications of all maritime settlements which may be taken from the English; it may, however, be proper to except Vizagapatam, by reason of its being so nearly situated to Bemelipatana, which in that case would be enriched by the ruin of Vizagapatam; but as to that, and the demolition of all other places, the Sieur de Lally is to consult the Governor and Superior Council of Pondicherry, and to have their opinion in writing; but, notwithstanding, he is to destroy such places as he shall think proper, unless strong and sufficient arguments are made use of to the contrary; such, for example, as the Company being apprehensive for some of their settlements, and that it would then be thought prudent and necessary to reserve the power of exchange in case any of them should be lost. Nevertheless, if the Sieur de Lally should think it too hazardous to keep a place, or could not do so without dividing or weakening his army, then his Majesty leaves him to act as he may deem proper for the good of the service.

“The Sieur de Lally is to allow of no English settlement being ransomed, as we may well remember that, after the taking of Madras last war, the English Company in their Council of the 14th of July, 1747, determined that all ransoms made in India should be annulled. In regard to the English troops, both officers and writers belonging to the Company, and to the inhabitants of that nation, the Sieur de Lally is to permit none of them to remain on the coast of Coromandel; he may, if he pleases, permit the inhabitants to go to England, and order them to be conducted in armed vessels to St. Helena. But as to the officers, soldiers, writers, and sailors belonging to the East India Company, he is to conduct them as soon as possible to the Isle de Bourbon, where the soldiers and sailors will be permitted to work for the inhabitants of that place, according to mutual agreement. It is by no means his Majesty’s intention that the English officers, soldiers, and sailors should be ransomed, as none are to be delivered up but by exchange, man for man, according to their different ranks and stations.

“If the exchange of prisoners should by chance be settled at home between the two nations, of which proper notice will be given to the Sieur de Lally, and that the islands of France and Bourbon should have more prisoners than it would be convenient to provide for, in that case it will be permitted to send a certain number to England, in a vessel armed for the purpose. No English officers, soldiers, &c., are to be permitted to remain in a place after it is taken; neither are they to retire to any other of their settlements.

“The Sieur de Lally is not in the least to deviate from the above instructions and regulations, unless there shall be a stipulation to the contrary; in which case the Sieur de Lally is faithfully and honestly to adhere to the capitulation.

“The whole of what has been said before concerns only natives of England; but as they have in their settlements merchants from all nations, such as Moors, Armenians, Jews, Pattaners, &c., the Sieur de Lally is ordered to treat them with humanity, and endeavour by fair means to engage them to retire to Pondicherry, or any other of the Company’s acquisitions, assuring them at the same time that they will be protected, and that the same liberty and privileges which they before possessed among the English will be granted them.

“Among the recruits furnished to complete the regiments of Lorrain and Berry, there are three hundred men from Fisher’s corps, lately raised, and as it is feared there will be considerable desertions among these new recruits, the Sieur de Lally may, if he pleases, leave them on the Isle de France, and replace them from the troops of that island.”

Before leaving France, Lally had placed his son, Trophine Gerard, who had been born at Paris on the 5th March, 1751, at the College of Harcourt, intending that he should ultimately follow the profession of arms.

Though impetuous and at times apt to be somewhat overbearing, Lally was eminently fitted for command. He possessed secrecy, with a ready facility for quick and judicious decision. His talent was evinced by the manner in which he established magazines, extended his posts and defences, and made himself acquainted with the character and features of the country which was to be the scene of his future operations. His lofty demeanour, talent, tact, and bravery inspired his troops with confidence and an assurance of conquest. If Lally was fond of glory, he was also fond of flattery; and though a strict disciplinarian, he was somewhat too partial, perhaps, to levying contribution on the conquered provinces; but while his enemies in after years averred that he was grasping, they never denied that he was lavish and liberal when the king’s service required him by spies to obtain intelligence of the strength and designs of the enemy.

The Count d’Aché, Chef d’Escadre, encountered such adverse winds that he was nearly twelve months on his voyage; thus the Chevalier des Soupirs, having wearied of waiting at the Mauritius, sailed towards the coast of Hindostan, and reaching Pondicherry (or Puducheri), disembarked his troops.

This town was the capital of the French settlements in India, being restored to them by the Dutch after the Treaty of Ryswick. It occupied a good position in the rich, fertile, and populous Carnatic, a country studded by an incredible number of forts and strongholds. Their erection was an indispensable necessity in a level district full of open towns, subject to the sudden attacks of hordes of native cavalry. The sovereigns of the Carnatic must have possessed at one period immense wealth and power, for the number and magnitude of their pagodas, and the indications that remain of ancient riches, grandeur, population, industry and art, impress the mind with wonder.

At this crisis the funds and forces of the British in that part of India were so small, that they could scarcely bring one hundred soldiers into the field. Madras, one of their principal places, sixty-three miles distant, was an open town; Fort St. David was in ruins, with a garrison of only sixty invalids. A fortnight would have enabled the Chevalier, with his 2000 men, to reduce the whole coast of Coromandel; but M. des Soupirs was quite unskilled in the art of carrying on war in a country so new to him, and remained inactive, though the French had many losses to repair, having been recently driven from all their wealthy settlements in Bengal by the victorious English.

Eight months after his arrival, on the 25th April, 1758, the Chef d’Escadre anchored in the roadstead before the sandy plain occupied by Pondicherry, and Lally disembarking his troops and treasure, marched into the town, the governor of which, M. de Leyrit, received him with a salute of cannon. At the peace of Amiens, the French population of Pondicherry amounted to 25,000, exclusive of the blacks, who were treble that number. Its revenue was then 40,000 pagodas; but it was a place destitute of natural advantages, its vicinity producing only palm-trees, millet, and a few herbs.

Weary of his long voyage, and anxious to fulfil his orders, which comprehended the total destruction of every British fortification that fell into his power, the ardent and gallant Lally lost not an hour in preparing for active operations. Next day, the 26th, he returned on board to sail for Cudalore, and in one hour after a powerful British fleet assailed the ships of Count d’Aché in the roadstead, where a French 74-gun ship was taken; but the rest fought a passage to the seaward, and favoured by the wind, and by superior sailing, anchored off Cudalore, a town situated fifteen miles from Pondicherry, on the western shore of the Bay of Bengal.

This little town, which occupies the banks of the Pennar, had been obtained by the English East India Company from the Rajah of Gingee, so early as 1681, for the site of a factory, and had been fortified. Its garrison consisted only of ten invalids; but being assisted by the inhabitants, these brave fellows made so stout a resistance, that Lally was occupied three days in taking it. From thence he marched to Fort St. David, a settlement on the Carnatic coast, obtained by the English from a Mahratta rajah in 1691, and besieging it, after being seventeen days in open trenches, exposed to the broiling sun by noon and the baleful dews by night, gained it by capitulation on the 2nd of June, and levelled all its fortifications to the ground.

On the 10th he marched back to Pondicherry, and having resolved to assail Madras, despatched an officer in a small vessel to his naval Chef d’Escadre, with instructions to return and co-operate with him. But Admiral Pocock, who commanded the British squadron in those seas, had defeated M. d’Aché in two engagements, and by driving him sixty miles to the windward, had nearly cut off all communication between him and the army. And now the governor of Pondicherry announced that the town and its vicinity could not subsist Lally’s 4000 Frenchmen for more than fifteen days. On this he was compelled to march into the little kingdom of Tanjore (or Tanjowar), which lay one hundred and fifty miles southward, and there quarter his troops during the stormy and rainy season, while the naval squadron took refuge in port. The advance into Tanjowar was not made without a due pretence of wrong to adjust, for the rajah had refused to pay a government debt, which M. de Leyrit assured Count Lally to be more than due.

The discharge of five pieces of cannon against his little capital compelled the rajah to pay down treasure to the amount of 440,000 livres, and afford free-quarters to the French troops for two months, until tidings arrived that 800 British were marching against Pondicherry; upon which Lally immediately abandoned Tanjowar, and advanced to the relief of the Chevalier des Soupirs, who with a slender force was timidly preparing to evacuate the capital of French India.

On Lally approaching, on the 31st of August, the British detachment fell back on Madras, and now our indefatigable Irishman, full of the most sanguine hopes of expelling them from the vast peninsula of Hindostan, at once made new preparations for investing Fort St. George, their principal settlement on the coast of Coromandel; but scarcity of money, and the improper conduct of the naval Chef d’Escadre, retarded the operations, frustrated the bold intentions of Lally, and ultimately betrayed them to the enemy.

While sparing no exertions to officer and equip a body of sepoy infantry, he seized a Dutch ship, in which he found a sufficient quantity of specie to enable him to attack Madras; he then sent a message to the Count d’Aché not to leave the coast; but the count replied, that he required a recruit of seamen, and must return to France. Alarmed by such a threat, Lally offered him half of his soldiers for the marine service; but deaf alike to threats and entreaties, the count sailed for the Straits of Madagascar on the 1st of September, and left Lally to cope single handed with the British forces.

On summoning to his presence M. de Bussy, who commanded the French troops in that extensive region named the Deccan (or Country of the South), and M. Moracin, who commanded at the seaport of Masulipatnam, he found these officers were somewhat influenced by the same pride and disobedience which characterized the conduct of Count d’Aché; and thus, before they would obey, and march against Madras, they required that Lally should embody an additional thousand men. He immediately ordered M. Moracin to return to his post, which the British were approaching. M. Moracin dared to refuse or delay, and taken by surprise during his absence, Masulipatnam was lost to France for ever.

In the month of October, Lally, with his slender force, the flower of which was the valiant Regiment de Lorraine, marched without opposition into the extensive district of Arcot (which seven years before had been overrun by Colonel Clive), and after remaining there at free-quarters for five days, marched back to Pondicherry.

The army was now totally destitute of pay, and the commissariat had no supply but plunder, while the departure of the Count d’Aché cut off all succour or retreat by the seaward. Though numerous, the troubles of Lally were just commencing. Discouraged and disunited by the naval disasters of d’Aché, the French officers were alternately fired with ardour and depressed by despair. M. de Bussy offered to raise 400,000 livres in three hours, if he was permitted to re-enter the Deccan with a body of troops; but being loth to divide his little force, and believing the result to be incredible, Lally wisely declined. De Bussy then informed him that he had 240,000 livres belonging to the East India Company, which were at his service if he would be responsible for them; but Lally still more wisely declined to compromise his honour by appropriating the money of the merchants to the service of the nation. He resumed his preparations for the siege of Madras while the British fleet was absent from its shore; but this measure was vehemently opposed by the Governor of Pondicherry, M. Duval de Leyrit, who urged the wretched state of the commissariat and the empty military chest. Lally’s Irish spirit could ill brook such disputations, and, “pay or no pay,” he was for marching at once.

However, he was compelled to take the opinion of the General Council of Pondicherry, some of whom adhered to De Leyrit; but five, headed by M. le Comte d’Estaigne, offered their plate, to the value of 80,000 livres, towards the expense of the expedition. The true and generous Lally gave, from his private purse, 140,000 livres; and having thus in some measure collected the sinews of war, with his small head-quarter force, 2700 French, and a body of sepoys, he advanced towards Madras early in December.

A march of sixty-three miles brought Lally, on the 12th day of the month, in sight of the town, which, by its strength, wealth, and annual revenue in calicos and muslins, was of such great consequence, even then, to the growing English East India Company. The diamond mines were only a week’s journey distant, and the rumour of their priceless wealth, and splendid wonders, animated the French soldiers, as in three divisions they marched across the sunny plains of Choultry.

Madras, or Fort St George, was divided into two parts; one called the Black, and the other the White town. The former, Madraspatam, had been totally destroyed by the French in 1744, when they levelled to the ground every building that stood within three hundred yards of the fort. The walls of the latter, which rose above the centre of the English town were—as dispatches relate—all built of hard, iron-coloured stone, and defended by four gigantic bastions. The inner fort, or citadel, had a front of one hundred and eight yards; the outer fort consisted of half-moons, curtain-walls, and flankers, which, like the rusty-coloured ramparts of the town were studded by an incredible number of cannon. In short, the aspect of Madras, with its mansions covered by snow-white chunam, is delightful from the ocean, and magnificent from the land. On the latter, its walls are moated by a river, which falls into the sea on that flat and sandy shore, where a white and furious surf is ever rolling in mountains of foam.

As he crossed the plains, Lally was briskly cannonaded by the field-pieces of the enemy, and lost many officers and men; but, advancing steadily, took possession of Ogmore and Meliapore (or San Thomé), an old town of the Portuguese, who had built there a large church above a grave reputed to be that of St. Thomas, who had been murdered by a tribe that dwelt in the vicinity, and whose right legs, after that sacrilegious act, were, according to Dr. Fryar, swollen to the size of those of elephants.

Colonel Lawrence, a gallant and resolute officer, who commanded the garrison of Madras, was ably seconded by Pigot the governor, by Colonel Draper, Major Caillaud, and other gentlemen. Thus Lally encountered the most determined resistance. The garrison consisted of 5000 men; of these, 1600 were regular troops of the British line, 300 were sepoys, and 400 were servants of the East India Company. Lawrence retired to the island in order to prevent the French from obtaining possession of the island bridge, and ordered all the posts to be occupied in the Black Town, which was triangularly shaped, and surrounded by a fortified wall.

At daybreak, on the morning of the 14th December, Lally sent forward M. de Rillon at the head of his regiment, which assailed the Black Town with great spirit, and after giving and receiving several severe discharges of musketry, during a contest of some hours, gained the place, driving back the British, who retired by detachments into the fort or citadel of Madras. This successful movement was followed by an advance of the Regiment de Lorraine, to keep the ground De Rillon had won; but within an hour, a grand sortie was made upon them by a body of British infantry, led by Colonel Draper, who behaved with great personal bravery.

Shrouded in smoke, he led a charge of bayonets against the Regiment de Lorraine; a furious mêlée ensued, and the French must have been driven back, or cut off, had not Lally sent forward another detachment, with some sepoys, to sustain the troops of M. de Rillon. A great number of officers and men were shot or bayoneted on both sides; but Colonel Draper was compelled to retreat, for his grenadiers gave way in a somewhat discreditable manner. After this, the garrison of Madras contented themselves by defending their works, being too weak to engage in sorties beyond them.

Colonel, afterwards Sir William Draper, was that preux chevalier who afterwards conquered Manilla, and became a paramount judge in all matters of military etiquette, and who, in his celebrated letter to Junius, expressed a hope that he would never see officers pushed into the British army who had nothing to lose but their swords.

Thus encouraged, by hemming in the enemy, Lally continued to push his approaches, and build batteries. Meanwhile M. de Lequille, another Chef d’Escadre, had arrived at the Isle de France, with four ships of war and three millions of livres, destined for the service of the French India Company. When about to leave the isle for the roads of Pondicherry, he unfortunately met the discomfited fleet of the Count d’Aché, who, being his superior officer, prevented him from proceeding, and removed the treasure on board his own ship, taking upon himself to send only one million of livres to the Count de Lally, in a small frigate, which reached Pondicherry on the 21st December, 1758.

This supply enabled Lally to press the siege with greater vigour, and to pay his French soldiers and Indian levies a portion of their arrears; but the blacks were of little service to him during the operations. M. Lally erected several batteries against the Black Town and Fort St. George; one of these, called the Grand Battery, was 450 yards distance from the glacis. They opened on the 6th January, 1759; after which they maintained a continued discharge of shot and shells for twenty days, the pioneers pushing on the trenches until their sap had reached the base of the glacis, within pistol-shot of the parapets. Then Lally formed another and loftier battery, on which he placed four pieces of heavy cannon. It opened on the 31st of January; but for five consecutive days the artillerists were compelled to close up their embrasures with fascines and earth, for the superior fire of the fort was not to be withstood, and it soon compelled them to abandon their redoubt. The Grand Battery, however, still continued a fire, which was so well directed, that it dismounted or broke twenty-six pieces of cannon and three mortars, beating down the wall and effecting a considerable breach.

During these operations, Lally had somewhat needlessly bombarded the town, to terrify the inhabitants, and demolished a number of their houses; but the precautions of Governor Pigot, the vigilance, valour, and experience of Colonels Draper, Lawrence, and Major Brereton repelled every attack; and thus, after the 5th of February, the fire of Lally’s batteries gradually diminished from twenty-three to six pieces of cannon. Money, powder, and shot became scarce together; he had lost many of his bravest men; two months had elapsed, and still the British standard waved above the fort of Madras. During this period the remonstrances which Lally sent frequently to France for succour, describe the deep anxiety he felt for the success of a cause in which his honour was implicated; and so keen and bitter did this feeling become, that at times, when aggravated by an illness incident to the climate, his reports and dispatches are remarkable for containing occasional sentences expressive of horror and distraction.

His general chagrin at the conduct of Count d’Aché and others is strongly portrayed in the following letter, which he addressed from the trenches at Madras to the Governor of Pondicherry, and which had been intercepted:—

“M. Duval de Leyrit,—A good blow might be struck here; there is in the roads a 20-gun ship laden with all the riches of Madras; she will remain there till the 20th. The Expedition is just arrived, but M. Gerlin is not a man to attack her, for she made him run away once before. The Bristol, on the other hand, did but just make her appearance before San Thomé, and on the vague report of thirteen ships coming from Porto Nova, she took fright, and, after landing the provisions with which she was laden, she would not stay even long enough to take on board twelve of her own guns, which she had lent us for the siege (of Madras).

“If I was to judge of the point of honour of the Company’s officers, I would break him like glass, as well as some others of them.

“The Fidele, or the Haerlem, or even the aforesaid Bristol, with her twelve guns restored to her, would be sufficient to make themselves masters of the British ship, if they could get to windward of her in the night. Maugendre and Tremillier are said to be good men, and were they employed to transport 200 wounded we have here, their service would be of importance. We remain in the same position; the breach made these fifteen days; all the time within fifteen toises of the place, and never holding up our heads to look at it. I believe we must, on our return to Pondicherry, learn some other trade, for this of war requires too much patience.

“Of the 1500 sepoys who attended our army, I believe nearly 800 are employed upon the road to Pondicherry, laden with pepper, sugar, and other goods; and as for the coolies, they have been employed for the same purpose since the first days we came here. I am taking my measures from this day to set fire to the Black Town and to blow up the powder-mills.

“You will never imagine that fifty French deserters and 100 Swiss are actually stopping the progress of 2000 men of the king’s and Company’s troops, which are still here existing, notwithstanding the exaggerated accounts that every one makes, according to his own fancy, of the slaughter that has been made among them; and you will be still more surprised if I tell you that, were it not for the combats and four battles we sustained, and for the batteries which failed, or (to speak more properly) which were unskilfully made, we should not have lost fifty men from the commencement of the siege to this day. I have written to M. de Larche, that if he persists in not coming here, let who will raise money upon the Poleagers for me, I will not do it! And I renounce—as I informed you a month ago—meddling directly or indirectly with anything whatever that may relate to your administration, civil or military. For I would rather go and command the Caffres of Madagascar than remain in this Sodom, which the fire of the English must sooner or later destroy, if that from heaven should not. I have the honour to be, &c.,

“Lally.

“P.S.—I think it necessary to apprise you that, as M. des Soupirs has refused to take upon him the command of this army, which I have offered him, and which he is empowered to accept, by having received from the Court a duplicate of my commission, you must necessarily, with the council, take it upon you. For my part, I undertake only to bring it back either to Arcot or Sadraste. Send, therefore, your orders, or come yourselves to command it, for I shall quit it upon my arrival there.—L.”

Though his cannonade had been diminished to only six pieces, Lally had advanced his sap along the seashore by cutting a trench about ten feet broad, with traverses to cover the soldiers, until he embraced the whole north-east angle of the covered way, from whence the Regiment de Lorraine, by a well directed mousquetade, drove the besieged in disorder. An attempt to open a passage into the ditch by mining failed, for the mine was sprung without effect.

Meanwhile Major Caillaud and Captain Preston, a Scottish officer, with a body of sepoys, another of Indian cavalry, and some European soldiers drawn from the British garrisons at Trinchinopoli and Chingalaput (which Clive when a captain had taken from the French in 1752), hovered on the roads a few miles from Madras, blocking up the avenues, cutting off succour and provisions from Pondicherry, thus compelling Lally four times (as his better states) to drive them back by detachments. These measures successfully retarded the siege until the 16th February, when, at the very time he was preparing for a grand assault at point of the bayonet, his Britannic Majesty’s ship Queensberry, commanded by Captain Kempenfeldt, the Company’s ship Revenge, and four other vessels, having on board 600 men of the 79th, or Colonel Draper’s regiment, with a great supply of provision of every kind, came to anchor in the roadstead, and the troops were immediately disembarked and marched into Madras. The rage and mortification of Lally were now complete!

He had encountered innumerable difficulties occasioned by the scarcity of money and munition, by the wretched supplies of the Government commissaries and contractors, by the conduct of Count d’Aché and others, by the sinking of his soldiers’ courage before the obstinate defence of the besieged; and now, with Kempenfeldt’s arrival all hope of success vanished. After maintaining a smart cannonade until the night of the 16th closed over Madras, Lally abandoned his trenches, and was compelled by scarcity of horses to leave forty pieces of cannon behind him: he blew up the powder-mills of Ogmore and retreated into Arcot.

Soon after this siege had been abandoned, the British received from home another reinforcement of 600 infantry, and on the 16th April the main body of their troops, which had been centred at Madras for its protection, took the field in three divisions against Lally, under the command of Major Brereton. The Chevalier des Soupirs felt the first brunt of this movement, being driven by the Major from Conjeveram, a large and handsome town, principally inhabited by Brahmins, which lies forty-four miles from Madras, and had the chief manufacture of turbans and red handkerchiefs. Major Forde, with another division, took by assault the town of Masulipatnam, the governor of which, M. Moracin, was still absent, as before related. The garrison, which was commanded by the Marquis de Conflans, had been weakened by the withdrawal of its soldiers to the siege of Madras. Thus the commerce of Britain secured a sea-coast of at least eight hundred miles in length along a country teeming with wealth and commerce, while that of France was almost confined to the narrow limits of Pondicherry. The third division of British under Colonel Clive was meanwhile advancing from the province of Bengal to assist the Rajah of Visanapore, who had driven the French out of Vizagapatam, and hoisted thereon the British flag.

The first severe shock sustained by the arms of Britain in the East was given by the gallant Lally in person. Sensible of the importance of such a place as Conjeveram, which with the fort of Chingelpel, commanded all the adjacent country and secured the British conquests to the northward, he marched towards Major Brereton, and took up a strong position at Vandivash. There he cantoned his troops until the month of September, when Brereton, on receiving 300 men under Major Gordon, from Colonel Coote’s Bengalese force, resolved on beating up the French in their quarters. Accordingly, on the 14th March he advanced from Conjeveram, at the head of 400 European infantry, 7000 sepoys, seventy European and 300 native horsemen, with fourteen pieces of artillery.

After capturing the fort of Trivitar, he advanced against the village of Vandivash, where Lally, although still struggling with a severe illness, had formed a strong intrenched camp, the lines of which were protected by a redoubt commanded by a rajah, and mounted with twenty pieces of cannon worked by Indians, under the directions of a single French cannonier.

At two on the morning of the 30th September the British attacked the village on three points, and on all with equal fury and determination. The French infantry, 1000 strong, made a spirited resistance; and the moment daylight broke, the guns of the rajah poured a storm of grape-shot upon the ranks of the enemy.

Lally did all that ability and gallantry could inspire to animate his troops; but being deserted by his black pioneers, who (like those of Brereton) fled at the moment of attack, the French were discouraged, and retired beyond a deep dry ditch, from whence the regiments of Lally and Lorraine made a succession of desperate sallies on the British, until, seeing that the column of Anglo-Indian horse were watching for an opportunity to fall upon his flanks, Lally, to preserve his little force from utter ruin, brought up his reserve to cover the retreat, and fell back, after the loss of many gallant chevaliers and 400 soldiers. Brereton and Gordon remained encamped in sight of the fort for some days; but the approach of the rainy season compelled them to retire into Conjeveram.

The Fort of Vandivash was afterwards garrisoned by French and sepoys, while another column of King Louis’s troops assembled in Arcot, under Brigadier-General the Marquis de Bussy, who endeavoured to levy as many sepoys as possible. These native troops, whose now familiar name is derived from Sepahe, the Indian word for a feudatory chief or military tenant, have ever made excellent soldiers, having an inborn predilection for arms. The success at Vandivash, for giving the British even a check was now deemed almost equal to a victory, made Lally conceive the idea of besieging Trinchinopoli; but again the folly or the treachery of the naval Chef d’Escadre baffled his intentions.

After having a third engagement with the British fleet on the 4th September, when with eleven ships of the line he was as usual defeated by Admiral Pocock with nine, the Count d’Aché, on the 17th, reached the roads of Pondicherry, from whence he wrote to the Count de Lally, then in position before Vandivash, offering to place at his disposal, for the king’s service, 800,000 livres in piastres and diamonds, being the plunder of a British ship which he had taken at sea, and which he begged the lieutenant-general to receive as part payment of the two millions so improperly detained in the preceding year at the Isle of France. He concluded his dispatch by a notification that on the following day, the 18th September, he would sail towards Madagascar.

At this time, when British valour was bearing all before it; when the powerful fortress of Karical (which the King of Tanjowar had ceded to France in 1739) was about to fall, and he lost, with all the fertile district around it; when the united fleets of Admirals Pocock, K.B., and Sir Samuel Cornish were sweeping along the shores of the Carnatic, reducing many places of minor importance, and by their cannon everywhere beating down the Fleur-de-lys of France; when Colonel Eyre Coote was pressing the French and their allies along the frontier of Bengal, and when the Prince of Vizanapore and other native rajahs were in open revolt against King Louis,—the announcement of the Chef d’Escadre filled the colonists with fear and confusion. Indignant and exasperated, Lally would have left the camp and sought Count d’Aché in person; but at that crisis, being so reduced by sickness that he could not quit his bed, he sent a deputation of field officers to represent the necessity of his remaining in the immediate vicinity of the Carnatic coast; of his co-operating with the land forces, and conjuring him by all means to suspend the execution of a design so pregnant with disaster to the Indian interests of his Most Christian Majesty. But nothing that these officers could urge, or their united eloquence suggest, would avert the fatal purpose of the Count d’Aché, who put to sea, and once more left the disheartened soldiers of King Louis to their fate.

Immediately upon this Lally assembled the Council and drew up a solemn PROTEST against the unaccountable conduct and sudden departure of the Chef d’Escadre and his fleet, proclaiming that he—and he alone—would be responsible if Pondicherry, the capital of French India, with all its territory fell into the hands of the British army and revolted rajahs. The “protest” was dated on the 17th of September, 1759, and was unanimously signed in the Hall of Fort Lewis, at Pondicherry, by Lally himself and the following gentlemen:—

“Duval de Leyrit, Renaut, Barthelmy, Chevalier des Soupirs, Michael Lally, Bussy, Du Bois, Carrière, Verdières, Duré, Gaddeville, Du Passage, Beausset, Renaut, De la Salle, Guillart, Porcher, Père Dominique, Capucin Prêtre de la Paroisse de Notre Dame des Anges, F.S. Lavacier, Supérieur Général des Jesuites Français dans les Indes, L. Rathon, Supérieur Général des Missions Etrangères, Poitier de Lorme, Duchatel, Audouart, Aimar, Combaut d’Authenil, Goupil, Keisses, J.C. Bon, De Wilst, Banal, Rauly, Termelin, Sainte Paul, J.B. Launay, Deshayes, Fischer, Du Laurent, Audager du Petit Val, D’Arcy, Medin, Dioré, Bertrand, Legris, Miran, Bourville, F. Nicolas, Du Plan, De Laval, Borée, D. l’Arché, Bayelleon de Guillette.”

The count had already sailed; but strong currents and adverse winds, however, met his fleet, which was driven far to the north; thus the protest of Lally overtook him at sea. Influenced by its tenor, he returned to Pondicherry, and after remaining one week in the roadstead, again departed for his favourite island of Madagascar, and for sixteen months Lally and his soldiers heard no more of him.

The Governor and Council of the British India Company at Madras having heard that Lally had sent a detachment of his forces southward and threatened Trinchinopoli, determined that Colonel Eyre Coote, who had recently arrived in the East, should take the field and drive it back.

The French officers had been fortunate in acquiring the favour of many of the Indian chiefs. Thus in 1755 the King of Travancore employed M. de Launay to discipline 10,000 Naires of Malabar in the mode of the European infantry; and thus M. de Lally, who had won the alliance of Salubetzingue, sovereign of the whole country, expected the arrival of his brother Bassuletzingue with a column of 12,000 Indians. When more than a hundred miles distant from the French army, the prince sent a Rissaldar to request that an officer of rank with a body of French should be sent to facilitate their junction. Lally immediately despatched the Marquis de Bussy on this service, with a detachment which joined the prince beneath the walls of Arcot. In twelve days all that was necessary might have been done; but the loitering marquis spun out the time to no less than two-and-forty. While Lally was totally unable to account for his absence, a dangerous ferment arose in the camp of Prince Bassuletzingue, there being no pay for his soldiers, as M. d’Aché’s diamonds were yet unsold; and during the delay the British troops under Colonel Coote (aware that Lally could not begin a campaign without cavalry) suddenly made themselves masters of Vandivash on the 30th November, after having breached the walls. Thus, by the indolence of M. de Bussy one of the most important fortresses on the coast was lost, and its garrison of 900 men taken, with forty-nine pieces of cannon and a vast quantity of ammunition.

On the 10th December they took Cosangoli, which was bravely defended by a mixed garrison of French and sepoys under Colonel O’Kennely, an Irish officer; who, after his guns were dismounted, capitulated and marched out with all the honours of war. With 100 Frenchmen he joined Lally, but 500 of his sepoys were disarmed and dismissed by Coote.

The double and dangerous success of this vigilant and enterprising officer compelled Lally to attempt a decisive demonstration for the recapture of Vandivash; but Coote, who had completely superseded Brereton in the command, was an officer who ably defended the conquests his bravery had made.

Having now somewhat recovered his health and strength, on the 10th January, 1760, the Lieutenant-General du Roi marched towards the captured fortress at the head of 2200 Frenchmen, and about 10,000 native troops. Among the latter were 1800 blacks called the Regiment de Bussy, 300 Caffres, and 2000 cavalry obtained from a Mahratta chief, with whom Lally had concluded a treaty, as soon as he found himself disappointed by Prince Bassuletzingue. They were all clothed and armed after the picturesque fashion of their native country (which extends across the whole peninsula of Hindostan) and were led by a Rissaldar, or commander of independent horse. He had twenty-five pieces of cannon with him.

He came in sight of the British on the banks of the Poliar, a broad and sandy river, the bed of which was quite dry; though in the middle of October, when the winter usually commences, and the rain descends in torrents, the river is sometimes half-a-mile broad, and flows towards the ocean with the greatest fury. There the adverse hosts hovered in sight of each other, until after succeeding in destroying some magazines which were in Colonel Coote’s rear (the loss of which prevented his troops from acting in the field for some days after), Lally with his 12,000 men suddenly invested Vandivash, against which his batteries opened with such effect, that a broad and practicable breach was soon made in the outer bastion, and now it was hoped that by one bold assault the captured fortress would be re-won, and with it the entire disputed territory.

But at the very time when Lally was about to lead on the assault, Coote with 1700 European and 3000 black troops, fourteen pieces of cannon, and one howitzer, came suddenly upon his rear to relieve the garrison.

Exposed to the cannon of the fort on one side, and to the troops of Coote on the other, Lally found himself critically situated; but, turning like a lion at bay, he drew off from his trenches, and rapidly formed in order of battle to face this new enemy, on the 21st of January.

Both armies were in high spirits and eager to engage.

About nine in the morning they were two miles apart. Coote having advanced with his cavalry and five companies of sepoys, Lally sent forward his Mahratta horse to meet them; but these, on being galled by two pieces of cannon, retired with precipitation. During this the colonel had succeeded in completely reconnoitring the position of Count Lally, whose forces were ably and judiciously placed, till the British made a movement to the right, which obliged him to alter and extend his left flank.

While the lines were three-quarters of a mile apart the cannonading began on both sides, and was continued with deadly precision and effect until noon, when Lally sent forward a small party of his European cavalry to charge the British left. A few companies of sepoys and two guns sent forward by Coote soon drove these in rear of their own army, and as the forces still continued approaching, by one o’clock the roar of musketry became general along both lines from flank to flank, and that broad plain on which a cloudless sun was shining became shrouded in snow-white smoke.

Undaunted by the cowardice of his cavalry, the hot-blooded Lally now threw himself into the line of his infantry, and at the head of the Regiment of Lorraine fell impetuously upon the British. Colonel Coote was on foot and at the head of his own regiment to receive them.

After giving and receiving two discharges of musketry, the Regiment de Lorraine rushed on with a fury that threatened to sweep all before it. Lally was in front, sword in hand; the bayonets crossed—the British line was broken; but though a momentary confusion followed, it was not driven back. A series of bloody single combats ensued, with the charged bayonet and clubbed musket; but these were of brief duration; for in three minutes the Regiment of Lorraine was broken in turn, routed, and driven back in headlong confusion, over a field strewed with their own killed and wounded. The explosion of a tumbril in rear of the French line created an additional confusion, of which Coote lost not a moment in taking advantage.

He ordered Major Brereton to advance with the regiment of Colonel Draper (who had returned to Europe for the benefit of his health), and by wheeling to the right to fall on the French left, and seize a fortified post which they were on the point of abandoning.

This service was performed with the utmost bravery; the French left was routed and driven pell-mell upon their centre. Draper’s regiment was the 79th, not the present Cameron Highlanders, but a corps which was disbanded in 1763. All had now become confusion among the enemy, but the gallant and accomplished Brereton fell mortally wounded.

“Follow—follow!” he exclaimed to some soldiers who loitered near him; “follow and leave me to my fate!” He soon expired; led by Major Monsoon, the regiment advanced impetuously on, and after a vain and desperate attempt, made by the Chevalier de Bussy, with Lally’s regiment, to repel it, the French and their allies were completely routed in every direction by two o’clock in the afternoon. The Regiment de Lally was almost cut to pieces; the horse of Brigadier-General M. de Bussy was shot under him, and he was taken prisoner by Major Monsoon, to whom he surrendered his sword.

Lally having brought up his fugitive cavalry, formed them in rear of his infantry, and enabled these to make a secure though precipitate retreat, leaving on the field a thousand men killed and wounded, with fifty prisoners, including the Marquis de Bussy, Quartermaster-General le Chevalier de Gadville, Lieutenant-Colonel Murphy, three captains, five lieutenants, many other officers, and twenty-two pieces of cannon.

Coote lost 260 killed and wounded. Among the former was the gallant Brereton. Maréchal Charles Grant, Vicomte de Vaux, affirms that the losses were equal on both sides.

Covering the foot by the cavalry, Lally conducted his routed forces with considerable skill and good order to Pondicherry, while Coote lost not a moment in pursuing the advantage he had gained. Dispatching the Baron Vasserot towards that place with 1000 horse and 300 sepoys, and with orders to ravage and lay waste all the French territory in and around it, he advanced in person against Chittipett, a small town and fort in the Carnatic, which, after a defence of two days, was surrendered on the 29th January, 1760, by the Chevalier de Tillie, who with his garrison remained prisoners of war.

On the 2nd February he reduced the fort of Timmary on the Coromandel coast, and pushing on to Arcot, the capital, opened his batteries and dug his approaches within sixty yards of the glacis. The garrison, which consisted of 250 French with 300 sepoys, defended the place until the 10th, when they surrendered as prisoners of war, delivering up twenty-two pieces of cannon and a large store of warlike munition.

Thus the campaign ended gloriously for Britain by the conquest of Arcot, and by hemming up the indefatigable but most unfortunate Lally in the fortifications of Pondicherry, the capital of French India, which was soon fated to become the last scene of his valour and achievement.

Surat, a place of great consequence on the coast of Malabar, was taken by a Bombay detachment, which destroyed the French factory. The English had obtained a settlement there from King Jehan Jeer in the year 1020 of the Hijerah. By sea the operations had been carried on with equal vigour. On the 4th September, 1759, an engagement had taken place between the fleets of Count d’Aché and Admiral Pocock, who obliged the former to sheer off with great loss. In April, the fortress of Karical had fallen, and by that time Admirals Pocock and Cornish had united their fleets in the roads of Pondicherry, within the gates of which nearly all that remained of the French forces in India were shut up, or encamped four leagues in front of it, under the command of the Count de Lally, barring the way by which he knew the British would march to an attack.

In Karical 174 pieces of cannon were taken, and to add to the disasters of the French, one of their 64-gun ships (the Haerlem) was burned in the roads of Pondicherry by the British cruisers.

Encouraged by his long career of success, and by the pecuniary and political embarrassments of his enemy, Colonel Coote resolved on investing Pondicherry. The approach of the rainy season, together with the well-known reputation for skill, bravery, and resolution enjoyed by the general of the now almost ruined French India Company, caused a regular siege to be considered impracticable; “it was therefore determined,” says the Sieur Charles Grant, “to block up the place by sea and land.”

Lally had only 1500 Frenchmen with him; these were the remnants of nine different corps of the King’s and India Company’s Service; the cavalry, artillery, and invalids of the latter; the Creole volunteers of the Isle de Bourbon; the king’s artillery; the Regiments of Lally, Lorraine, Mazinis, and the battalion of India.

The British armaments on the coast were now much more considerable. On the land were four battalions of the line, and by sea were seventeen sail of the line, carrying 1038 pieces of cannon, the smallest being three 50-gun ships.

As the fortress of Pondicherry was as impregnable as nature and art could make it, Coote was perfectly aware that it could only be reduced by the most severe famine. It was also his opinion that with such an antagonist as Arthur Lally, a formal siege with regular approaches would prove perfectly futile with any force he could assemble; for, in addition to his French comrades, Lally had a strong force of armed sepoys, and a vast store of warlike munition, including nearly 700 pieces of cannon, and many millions of ball cartridges, all made up for service. The ramparts bore 508 pieces (independent of mortars), the walls were five miles in circumference, and had a deep broad moat before them. There were six gates and thirteen bastions. The cavalry of the French India Company openly deserted in great numbers, and were received with rewards by Colonel Coote. This exasperated Lally so much, that he erected gibbets all round Pondicherry in order to deter others from leaving the town or the lines before it.

To victual the place completely for the inhabitants and his garrison was the first care of Lally; for the town was large, and possessed an overplus of population, which gave him infinite cause for trouble and anxiety.

Pondicherry was surrounded by a number of forts, the defence of which, in all former sieges, had occasioned the inhabitants the utmost difficulty; but these were rapidly reduced, as all the adjacent country was in the hands of the British. The fleet of Sir Samuel Cornish came to anchor on the 17th March, and while Coote approached nearer by land, Lally, in order to retard him, retired from position to position, bravely disputing every inch of ground, until, in front of Pondicherry, he formed his famous lines, which he defended for three months with admirable skill and valour, thereby gaining sufficient time to have victualled the town for the half of a year. While thus holding the foe in check, he concluded a treaty with the Rajah of Mysore, who pledged himself to supply Pondicherry with provisions; but failed to perform his promise, and departed with his people. A short time afterwards, Lally resolved to attempt a sortie, and on the night of the 2nd September, 1760, he made a furious attack on Coote’s advanced posts, but was repulsed with great loss, and had seventeen pieces of cannon taken. Coote lost but a few privates.

The last of the fortified boundary, or chain of redoubts, was carried by storm on the 10th September; the French were driven in, and Coote had forty killed and seventy wounded; Major Monsoon had one of his legs torn off by a cannon-shot.

A body of Scottish Highlanders, who had just been landed from the Sandwich East Indiaman, behaved with their accustomed valour in this affair. Passing Draper’s grenadiers in their eagerness to get at the enemy, they threw down their muskets, and with their bonnets in one hand, and their claymores in the other, hewed a passage through a jungle hedge, fell with a wild cheer upon the soldiers of Lally, and cut a whole company to pieces. Only five Highlanders and two grenadiers were shot. The Highlanders were fifty in number, and were commanded by a Captain Morrison. They belonged to the 89th Highland Regiment, which had been raised among the Gordon clan in the preceding year.

After that night, the operations of Lally were confined to the walls of Pondicherry.

Of the guns taken by the Highlanders, seven were found to be 18-pounders, loaded to the muzzle with square bars of iron six inches long, jagged pieces of metal, stones and bottles. They were on Lally’s strongest battery, which was formed before a thick wood, one mile in front of Pondicherry, which could no longer have any succour from the seaward, as the Chef d’Escadre had sailed for Brest, where he arrived in April, 1761. Thus a 54-gun ship, a 36-gun frigate, and four Indiamen were left behind, and hopelessly shut up in the roadstead.

In the month of October, Admiral Stevens, who had relieved Admiral Cornish, sailed with his portion of the fleet for Trincomalee to refit, leaving five sail of the line, under Captain Haldane, to blockade Pondicherry, while Colonel Coote pressed on the investment by land. By their dispositions and vigilance, the dense population became distressed for provisions even before a siege was formally begun, and while the incessant rains rendered a closer conflict impracticable. The blockade was supported by a number of batteries judiciously posted; by these the garrison was harassed on one hand, while their supplies were cut off on the other; and these posts were gradually pushed nearer and nearer to the town, notwithstanding the deluge of rain, which had swollen the broad currents of the Chonenbar and the Gingi, two rivers that unite near it, and roll their tides together to the sea.

On the 26th November, the rains abated, and Colonel Coote directed his engineers to erect batteries in other places; from whence, without being exposed, they could enfilade the works of the garrison, which was strictly closed in, and by the failure of the Mysorean rajah to fulfil his promise, was now enduring the utmost privations from scarcity of food. Lally was compelled to turn out of the town a vast multitude of native women and children; but Coote drove them back again, and, as the batteries were firing at the time, a great number of these poor wretches were slain or severely wounded.

During these operations, Captain Sir Charles Chalmers of Cults, a gallant Scottish baronet who served in Coote’s artillery, died of fatigue. He possessed only the honours of his family, their estates having been forfeited for adherence to the house of Stuart about fifteen years before.

On the night of the 7th October, the armed boats of the British fleet were pulled with muffled oars into the harbour, and two ships were cut out, under the very muzzles of Lally’s cannon; but not before he had killed and wounded thirty officers and men. The prizes were the Balcine and Hermione, a frigate and a valuable Indiaman. In this affair Lieutenant Owen, of H.B.M. ship Sunderland, lost an arm.

To encourage the British, the Nabob of Arcot promised to divide among them fifty lacs of rupees on the day Pondicherry should surrender, and, as each lac was valued at 12,600l. sterling, the greatest enthusiasm prevailed among the officers, soldiers, and seamen: moreover, as all the French colonists who fled from other places had stored up their effects in Pondicherry, the treasure there was reputed to be enormous.

On the 26th September, Coote’s forces had been mustered at 3500 English and Scottish Highlanders, with 7000 sepoys, all of whom were strongly intrenched, having taken Arcupong, Villa Nova, and every French outpost, while fifteen sail of the line and three frigates swept the ocean to the seaward, cutting of all succour; indeed, none was ever afforded to the unfortunate Lally save by the Dutch settlers, who sent two unpretending boats; but even these were observed, and on being seized were found to contain 20,000l. in cash and many valuable stores. Every day provisions were becoming more and more scarce, and notwithstanding the weakness of his garrison, Lally was compelled to select 200 French and 300 black soldiers, whom he contrived to despatch towards Gingi for succour; but they were all cut off, and thus he found himself worse than before.

The scarcity increased, and now gaunt starvation and death met the eye on every hand; a thousand scenes of horror and distress occurred daily within the walls of Pondicherry. The soldiers of Lally and the citizens were compelled to eat the flesh of elephants, camels, and troop-horses; after which dogs, cats, and even rats were devoured. The count was frequently implored to surrender, but having now become sullen, revengeful, and determined, his lofty pride made him resolve to perish among the ruins of the French Indian capital, but never capitulate.

Twenty-four rupees were given for a small dog, and in some instances as many half-crowns.

On the 5th November, Lally dispatched a 54-gun ship, La Compagnie des Indes, to Trincomalee, a Danish settlement, for provisions; but after eluding the watchful blockading fleet, she was taken at sea by H.M. ships Medway and Newcastle, and with her loss all hopes of succour died away.

On the 9th November, Colonel Coote erected a ricochet battery for four pieces of cannon, at 1400 yards from the glacis (for the information of unmilitary readers, we may mention that ricochet firing means when cannon or mortars are loaded with small charges, elevated from five to twelve degrees, so that when discharged from the parapet, the shot may roll along the opposite rampart); this was more with a view to harass the French than damage their works; but meanwhile four other batteries were erecting in different places to rake and batter them.

One for four guns, called the Prince of Wales Battery, was formed near the sea-beach, on the north, to enfilade the great street which intersects the White Town.

A second, for four guns and two mortars, was formed to enfilade the counter-guard, before the north-west bastion, at a thousand yards’ distance, and in honour of the “Butcher of Culloden,” was called the Duke of Cumberland’s Battery.

A third, called Prince Edward’s, for two guns, faced the southern works at 1200 yards’ distance, to enfilade the streets from south to north, and cross the fire of the northern battery.

A fourth, on the south-west, at 1100 yards’ distance, and called Prince William’s Battery, was mounted with two guns and one mortar, to destroy the cannon on the redoubt of San Thomé.

Lally beheld all these preparations with calmness, and by inspiring his soldiers with something of his own fierce ardour, laboured to retard the work of the besiegers, whose batteries commenced a simultaneous fire at midnight on the 8th December. Lally’s cannoniers replied with the utmost vigour; they slew a master gunner, a subahdar of sepoys, and wounded a great many more.

On the 1st of January, a violent tempest of wind, accompanied by torrents of rain, had almost ruined the works of Coote, and blown the fleet off the coast. The French became elated by the delay this occasioned, and the consequent prospect of relief; but the sudden reappearance of Admiral Stevens with his vessels caused their hopes to fade away; and once more this little band of starving and desperate men betook them to their muskets and lintstocks; for, still pressing on, Coote, on the 29th, formed a fifth battery, called the Hanover, at only 450 yards’ distance, for ten cannon and three mortars, which opened a fire of shot and shell against the counter-guard and curtain.

At last, being driven frantic by their sufferings, the soldiers and citizens demanded that the place should be surrendered. Lally was immovable, but yet feeling keenly for what they endured, dissatisfied with the state of the French Indian affairs, and greatly exasperated by the disorderly conduct of his troops, and the baseness of their commissaries, he frequently burst into passionate exclamations which showed the keenness of his agitation.

“Hell has spewed me into this country of wickedness,” he said on one occasion, “and like Jonas I wait until the whale shall receive me into its belly!”

“I will go among the Caffres, rather than remain longer in this Sodom,” he exclaimed on another occasion.

But, nevertheless, he still defended the town like a good soldier, and on the disappearance of the British fleet during the storm, wrote the following letter to M. de Raymond, the Resident at Pullicot:—

“M. Raymond, the English squadron is no more! Out of twelve ships they had in our roads seven are lost, crews and all; four others are dismasted, and it appears that only one frigate has escaped, therefore lose not an instant to send us chelingoes upon chelingoes loaded with rice. The Dutch have nothing to fear now; besides—according to the law of nations—they are only to send us no provisions themselves, and we are no longer blocked up by sea.

“The saving of Pondicherry has once already been in your power. If you miss the present, it will be entirely your own fault. Don’t forget some small chelingoes—offer great rewards. I expect 17,000 Mahrattas in four days; in short, risk all! attempt! force all! but send us some rice, should it be but a half garse at a time.

“Lally.

“Pondicherry, 2nd January, 1761.”

The British fleet suffered considerably; many vessels which had to cut their cables, were totally dismasted, and the Queensberry, Newcastle, and Protector were driven on shore; while Le Duc d’Acquitaine of sixty-four guns (French prize), commanded by Sir William Hewitt, Bart., and the Sunderland of sixty guns, commanded by the Hon. James Colville, both foundered, and all on board perished. Captain Colville was the son of Lord Colville, of Culross, a Scottish peer, who died on the Carthagena expedition in 1740, and brother of Alexander Lord Colville, who in 1764 was Commodore in North America.

On the reappearance of Admiral Cornish with more of the fleet, the hope of the French sank again, and Lally, enraged at what he considered the mutinous repining of his soldiers, met their remonstrances with turbulence and contempt, and by an unwise, and perhaps over-strained exercise of authority, at this fatal and desperate crisis, most unfortunately contrived to render himself unpopular with the Governor, the Council, and the proud chevaliers of old France, who officered his little band of troops.

Still, however, the siege was pressed, and still the defence went on.

On the 5th January, Coote attacked the redoubt of San Thomé, sword in hand, at the head of a body of Scottish Highlanders and English grenadiers, and won it, thus silencing four 28-pounders; but two days afterwards, Lally retook it by 300 grenadiers, from the sepoys who were left in charge of it.

On the 13th Coote sent 700 Europeans, 400 Lascars, and a company of pioneers under a major, to erect another battery of eleven guns and three mortars. Under the clear splendour of an Oriental moon, these works were carried on within 500 yards of the walls; and this Batterie Royale was permitted to be erected without molestation, for in their sullen despair the garrison never fired a shot at it. On the 14th the Hanover Battery ruined the north-west bastion, and on the following day the Batterie Royale beat down the ravelin at the Madras gate; thus by the 15th of January a great and practicable breach was effected, and the cannon of the gallant Lally were silenced or dismounted.

In the evening a parley was beat, and four envoys came from the ruined walls towards the British trenches. These were Colonel Duré (Durie?) of the French Royal Artillery, Father Lavacer, Superior of the Jesuits, and two civilians. These were unprovided by “any authority from the Governor,” says Vicomte de Vaux; but Colonel Coote, in his dispatch to Mr. Pitt, affirms that they came direct from Lally with proposals for delivering up the garrison. In the town, at that moment, there were only three days provisions of the wretched kind described; thus the extremity of famine would admit of no hesitation. Rendered ungovernable by what they had endured, Lally’s officers declared the defence to be frantic obstinacy, and murmuring aloud, also averred that illness, pride, and the climate had disordered his imagination; and that it was criminal rather than valiant to defend an untenable fortress.

The following were the proposals of Lally, presented by Colonel Duré to Colonel Coote:—

“The troops of the king and Company, by want of provisions, will surrender themselves prisoners of war to his Britannic Majesty, on terms of the cartel, which I claim equally for all the inhabitants of Pondicherry, as well as for the exercise of the Roman religion, the religious houses, hospitals, chaplains, surgeons, serjeants, reserving and referring myself to the decision of our two Courts, in proportion to the violation of a treaty so solemn. (He refers to the treacherous capture of Chandernagore.)

“Accordingly M. Coote may take possession of the Villenour Gate at eight o’clock to-morrow morning; and after to-morrow, at the same hour, that of Fort St. Lewis.

“I demand, merely from a principle of justice and humanity, that the mother and sisters of Raza Sahib may be permitted to seek an asylum where they please, or that they remain prisoners among the English, and not be delivered into the hands of Mohammed Ali Khan, which are still red with the blood of the husband and father, which he has spilt, to the shame of those who gave them up to him; but not less to the shame of the commander of the English army, who should not have allowed such a piece of barbarity to be committed in his camp.

“As I am tied up by the cartel, in the declaration which I make to M. Coote, I consent that the Council of Pondicherry may make their own representations to him with regard to what may concern their own private interests as well as the interests of the inhabitants of the colony.

“Done at Fort Lewis, Pondicherry, 15th day of January, 1761.

“Lally.”

To these the Colonel replied briefly by stating that the capture of Chandernagore was beyond his cognizance, and had no relation to Pondicherry; that he merely required the soldiers of its garrison to yield as prisoners of war, promising that they should be treated with every honour and humanity; that he would send the grenadiers of his own regiment to receive possession of the Villenour Gate, and that of Fort St. Lewis; and that according to the kind and humane request of M. Lally, the mother and sisters of Raza Sahib should be escorted to Madras, and on no account be permitted to fall into the hands of their enemy, the Nabob Mohammed Ali Khan.

To eight articles proposed by Father Lavacer, Superior of the Jesuits, requiring that the inhabitants should be treated in every respect like subjects of his Britannic Majesty; that they should have full liberty to exercise the Catholic religion; that the churches should be rejected; that all public papers should be sent to France; and that forty-one soldiers of the Volunteers of Bourbon should be permitted to return to their homes—Colonel Coote declined to make any reply.

At eight o’clock on the morning of the 16th July, Lally with a bitter heart ordered the standard of France to be hauled down on Fort St. Lewis, and at that hour Coote’s grenadiers received the Villenour Gate from the Regiment de Lally, while those of the 79th Regiment took possession of the citadel. Thus fell Pondicherry after a blockade and siege which Lally’s skill and valour had protracted under a thousand difficulties for the long period of eight months, against forces treble in number to those he commanded.

Notwithstanding his fallen condition and the severe effects of a long illness, aggravated by the sultry climate, by bodily sufferings and anxiety, Lally marched out of the citadel with the air of a conqueror. “He is now as proud and haughty as ever,” says an officer (who beheld him) in a letter to a periodical of the time; “but his great share of wit, sense, and martial ability are obscured by a savage ferocity, and an undisguised contempt for every person below the rank of general.” This writer was ignorant of the high qualities of Lally, and the difficulties with which he had contended, or he would never have written thus.

According to the “exact state of the troops of his most Christian Majesty, under the command of Lieutenant-General Arthur Count de Lally, when he surrendered at discretion on the 16th of January, 1761,” he marched out with the following—a miserable and famished band, hollow-eyed and gaunt—the few survivors of the Indian war:—

| Artillery of Louis XV., officers and men | 83 |

| The Regiment de Lorraine, ditto | 327 |

| The Regiment de Lally, ditto (of the Irish Brigade) | 230 |

| The Regiment of the Marine, ditto | 295 |

| Artillery of the French India Company | 94 |

| Cavalry of ditto | 15 |

| Volunteers of Bourbon | 40 |

| The Battalion d’India | 192 |

| Invalides | 124 |

In all there were only 1400. One of their first acts was to cut their commissary to pieces. Among the officers of the king’s artillery was Jean Baptiste Louis Romée de l’Isle, the celebrated crystallographer, who was then secretary to a corps of engineers. The quantity of military stores delivered over by Lally to Coote is almost incredible.

There were 671 brass and iron cannon and mortars; 438 mortar-beds and carriages; 84,041 shot and shell, round, double-headed, and grape; 230,580 lbs. of powder; 538,137 rounds of cartridge for arquebuses, muskets, carbines, pistols, and gingals; 910 pairs of pistols; 12,580 other firearms; 4895 swords, bayonets and sabres; 1200 poleaxes, and every other warlike munition in proportion. Tidings of the fall of Pondicherry occasioned the utmost joy in Britain; and on Sunday, the 2nd August, there were prayers and thanksgiving in all the English churches.

On that day Lally arrived at Fort St. George a prisoner of parole. He had begged to be sent to Cudalore that he might have the attendance of French as well as British surgeons; but the Governor of Madras insisted upon his removal to that place, whither he conveyed him in his own palanquin.

A regiment of Highlanders garrisoned Pondicherry, and as Lally had destroyed many of the British fortifications, Colonel—afterwards Sir Eyre—Coote retaliated by blowing up the works and hurling the glacis into the ditch. The plunder acquired amounted to 2,000,000l. sterling. The quantity of lead discovered in the stores was immense. Lally found means to convey his own cash and Valuables (200,000 pagodas of eight shillings each) out of the garrison, but he was deprived of it by Coote’s orders.

The plunder of the magnificent palace was a subject for regret to the officers who beheld it. It had been built by M. Dupleix, a former resident, at the cost of one million. On the same day that Lally surrendered, his Scottish compatriot, M. Law, on whose assistance he had for a time mainly relied, was defeated by Major Carnac.

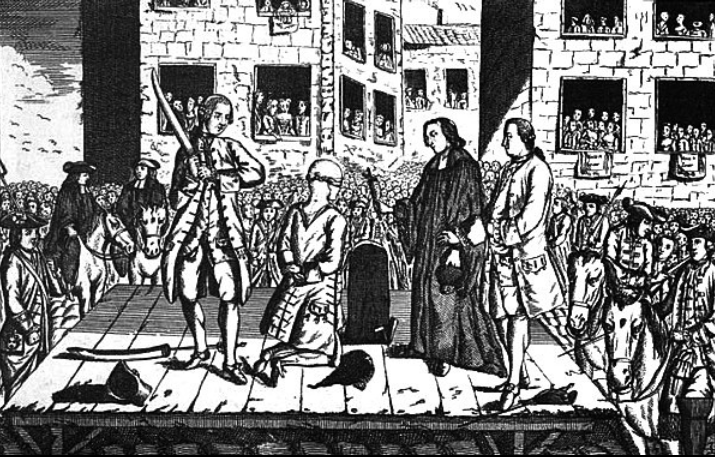

M. Law was a nephew of the famous financial projector, John Law, of Lauriston, near Edinburgh, who, in 1720, was Premier of France, and Comptroller-General of Finance—the same whose desperate schemes brought the kingdom to the verge of bankruptcy. M. Law had made himself useful to the Schah Zaddah, son of the late Mogul, in supporting the young prince’s hereditary claims, and enforcing his authority on the provinces of the empire. With 200 Frenchmen (principally fugitives from Lally’s outposts) he persuaded the schah to turn his arms against Bengal; and accordingly the young and rash prince entered that rich and fertile province at the head of 80,000 Indians, whose operations were directed by Law, and certain chevaliers his friends. In the eye of the British (who had then become the arbiters of Oriental thrones), the presence of the Scottish refugee and his followers was more prejudicial to the title of Zaddah than any other objection, and they joined the Subah of Bengal to oppose his progress. A battle ensued at Guya, when Major Carnac, with 500 British, 2500 sepoys, and 20,000 blacks, cut the vast force of the young prince to pieces, and took prisoner M. Law, with sixty French officers.