Editor’s note: The following comprises the fifth chapter of The Jews, by Hilaire Belloc (published 1922).

(Continued from Chapter 4: The General Cause of Friction)

CHAPTER V: THE SPECIAL CAUSES OF FRICTION

There are two special forces upon the Jewish side which nourish and exasperate the inevitable friction between the Jewish race and its hosts. It will be well to deal with these before passing to the corresponding forces upon our side. For to find a remedy it is necessary to diagnose the disease.

The two main Jewish forces which exasperate and maintain the sense of friction between the Jews and their hosts are first of all the Jewish reliance upon secrecy, and, secondly, the Jewish expression of superiority.

1. The Jewish Reliance upon Secrecy

It has unfortunately now become a habit for so many generations, that it has almost passed into an instinct throughout the Jewish body, to rely upon the weapon of secrecy. Secret societies, a language kept as far as possible secret, the use of false names in order to hide secret movements, secret relations between various parts of the Jewish body: all these and other forms of secrecy have become the national method. It is a method to be deplored, not because its indignity and falsehood degrade the Jew—that is not our affair—but rather on account of the ill-effects this policy produces on our mutual relations. It feeds and intensifies the antagonism already excited by racial contrast.

But before we go further it is essential to be just; for no one understands anything if he attacks it unjustly.

The Jewish habit of secrecy—the assumption of false names and the pretence of non-Jewish origin in individuals, the concealment of relationships and the rest of it—have presumably sprung from the experience of the race. Let a man put himself in the place of the Jew and he will see how sound the presumption is. A race scattered, persecuted, often despised, always suspected and nearly always hated by those among whom it moves, is constrained by something like physical force to the use of secret methods.

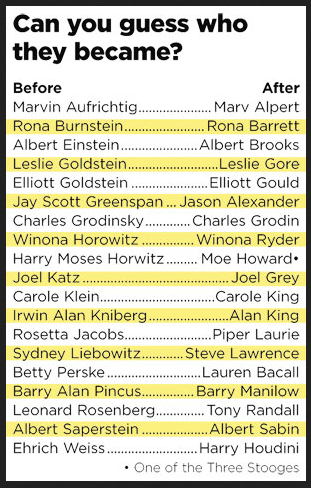

Take the particular trick of false names. It seems to us particularly odious. We think when we show our contempt for those who use this subterfuge that we are giving them no more than they deserve. It is a meanness which we associate with criminals and vagabonds; a piece of crawling and sneaking. We suspect its practisers of desiring to hide something which would bring them into disgrace if it were known, or of desiring to over-reach their fellows in commerce by a form of falsehood.

But the Jew has other and better motives. As one of their community said to me with great force, when I discussed the matter with him many years ago at a City dinner, “When we work under our own names you abuse us as Jews. When we work under your names you abuse us as forgers.” The Jew has often felt himself so handicapped if he declared himself, that he was half forced, or at any rate grievously tempted, to a piece of baseness which was never a temptation for us. Surely all this carefully arranged code of assumed patronymics (Stanley for Solomon, Curzon for Cohen, Sinclair for Slezinger, Montague for Moses, Benson for Benjamin, etc., etc.) had its root in that.

The Jew can plead something further in extenuation of this practice. Family names did not grow up naturally with them, as with us, in the course of the Middle Ages. The Jew retained, as we long retained in the middle and lower ranks of European society, the simple habit of possessing one personal name and differentiating a man from his fellows by introducing the name of his father. Thus a Jew in the sixteenth century was Moses ben Solomon, just as the Cromwells’ ancestor of the same generation was Williams ap Williams. He had not what we call a surname or family name. In the same way until varying dates, early in France and England and other Western countries, much later in Wales, Brittany, Poland and the Slav countries of the East, a man was known only by his personal name, distinguished, if that were necessary, by mentioning also the name of his father, or, in some cases, of his tribe.

Properly speaking the Jews have no surnames, and they may say with justice: “Since we were compelled to take surnames arbitrarily (which was the case in the Germanies and sometimes elsewhere as well), you cannot blame us if we attach no particular sanctity to the custom.” If a Jew of plain Jewish name was compelled by alien force to take the fancy name of Flowerfield, he is surely free to change that fancy name, for which he is not responsible, to any other he chooses. There was a good reason for the Government to force a name upon him. Only thus could he be registered and his actions traced. But forced it was, and therefore, on him, not morally binding.

All this is true, but there remains an element not to be accounted for on any such pleas. There are in the experience of all of us, an experience repeated indefinitely, men who have no excuse whatsoever for a false name save that advantage of deceit. Men whose race is universally known will unblushingly adopt a false name as a mask, and after a year or two pretend to treat it as an insult if their original and true name be used in its place. This is particularly the case with the great financial families. Some, indeed, have the pride to maintain the original patronymic and refuse to change it in any of their descendants. But the great mass of them concealed their relations one with another by adopting all manner of fantastic titles, and there can be no object in such a proceeding save the object of deception. I admit it is a form of protection, and especially do I admit that in its origin it may have mainly derived from a necessity for self-protection. But I maintain that to-day the practice does nothing but harm to the Jew. There are other races which have suffered persecution, many of them, up and down the world, and we do not find in them a universal habit of this kind.

Again, who can say that the bearing of a Jewish name today, or at any rate in the immediate past, is or was a handicap in commerce where Occidental nations were concerned? And as for the Eastern nations, the Jews there are so sharply differentiated that a false name can be of no service merely to hide the racial character of its bearer. There must be another motive present.

The same arguments apply for and against other forms of secrecy. A man may plead that if secrecy in relationship were not maintained the dislike of Jews would lead to false accusations. The Jew is highly individual, especially in intellectual affairs. He takes his own line. He expresses his opinions with singular courage. And such individual opinions will often differ violently from those of men with whom he is most closely connected. “Why,” I can understand some distinguished Jewish publicist in England saying, “should I be compromised by people knowing that such-and-such a Bolshevist in Moscow or in New York is my cousin or nephew? I am conservative in temperament; I have always served faithfully the state in which I live; I heartily disapprove of these people’s views and actions. If their relationship with me were known I should fall under the common ban. That would be unjust. Therefore I keep the relationship secret.”

The plea is sound, but it does not cover the ground. It is not sufficient to explain, for instance, the habit of hiding relationships between men equally distinguished and equally approved in the different societies in which they move. It does not explain why we must be left in ignorance of the fact that a man whom we are treating as the best of fellow-citizens should hide his connection with another man who is treated with equal honour in another country. There are occasions where national conflicts make the thing explicable. A Jew in England with a brother in Germany and a father at Constantinople might well be excused in 1915 for calling himself Montmorency. Yet we note that often where there is most need to hide the connection, the connection is not hidden at all. On the contrary, it is openly advertised. We all recollect the name of one Jewish financier who was most unjustly treated during the war. He had faithfully served this country and the breach of his connection with it was (to my mind at least, and I think to most people who can judge the matter) a very bad thing for Britain in the conflict. Yet there was here no change of name and no attempt to hide the connection between himself and his brother, who stood, in another capital, for the financial policy of our enemies.

Again, the Rothschilds, present in the various capitals of Europe, have never pretended to hide their mutual relationships, and no one has thought any the worse of them, nor has this open practice in any way diminished their financial power.

There must be more than necessity at work; I suggest that there is something like instinct, or, at any rate, an inherited tradition so strong that recourse to it seems natural.

Now it cannot be too forcibly emphasized that secrecy in any of these forms—working through secret societies, using false names, hiding of relationships, denying Jewish origin—specially exasperates this, our own race, among which the Jews are thrown in their dispersion. It is invariably discovered, sooner or later, and whenever it is discovered men have an angry feeling that they have been duped, even in cases where the practice is most innocent and is no more than the following of something like a ritual.

I doubt whether the Jews have any idea how strongly this force works against them. If a man were to say “my name is so-and-so; my father was born at such-and-such a place in Galicia; my brother is still there in such-and-such a business”—if he told us all that, he would not suffer upon our appreciating later on that members of his family abroad were connected with movements we disapproved: no, not even with a Government in active hostility to our own. Everybody knows the international position of the Jew. Everybody knows that he cannot avoid that position. Everybody makes allowances for it. And I conceive that the abandonment of this habit of secrecy is not only possible but would be very greatly to the advantage of the whole race.

Perhaps its most absurd form (not its most dangerous form) is the secrecy maintained by distinguished men with regard to their Jewish ancestors. They and their Jewish relations often suppress it altogether or, at best, touch on it rarely and obscurely. Why should they act thus? Take the case of two men at random out of hundreds whose names are universally known and by most people respected, the name of Charles Kingsley, the writer, and the name of Moss-Booth, the founder of the Salvation Army. Here are two men who in very different fields played a great part in English life and who both owed their genius and nearly all their physical appearance to Jewish mothers. I should have thought it to the advantage of the Jewish race and of the individuals concerned that this fact should be widely known. The literary abilities of Charles Kingsley, the organizing and other abilities of Booth are not lessened in people’s eyes, but, if anything, enhanced, by a knowledge of their true lineage. Yet the mention of that lineage is treated as though it were a sort of insult. I have heard it wrung out in some passionate plea for the Jewish race as a proof that they are not devoid of abilities, but never generally published.

Surely it would be more sensible to emphasize in every possible case the Jewish or partially Jewish origin of men who distinguished themselves, and thus to show under what a debt Europeans stand to the Jewish blood. To treat the matter as a sort of sacred labyrinth, as a mysterious temple into which one may now and then be allowed to peep is ridiculous. The Jews cannot have their cake and eat it too. If it is—surely it must be—in their eyes a matter for pride to belong to blood which they hold to be superior and to a tradition of such immense antiquity, then it cannot be at the same time a matter of insult. Yet the convention is desperately maintained by the Jews themselves. If a man tells me that he hates the English, and in reply I say, “That’s because you are an Irishman,” he does not fly at my throat. He takes it as a matter of course that the history of the English government in Ireland excuses his expression. So far from being insulted at being called an Irishman he would be insulted if you said he was not an Irishman. And so it is with many another nationality which has suffered oppression and persecution. I can find no rational basis for a contrary policy in the case of the Jews. Moreover the habit does this further harm: it makes men ascribe a Jewish character to anything they dislike, and thus extends undeservedly the odium against the race.

A foreign movement against one’s nation, an unpopular public figure, a detested doctrine, are labelled “Jewish” and the field of hate, already perilously wide, is broadened indefinitely. It is useless to say, “The Jews do not admit the connection, the names are not Jewish, there is no overt Jewish element.” He answers, “Jews never do admit such connection; Jews admittedly hide under false names; Jewish action never is overt.” And—as things are, until they change—there is no denying what he says. His judgment may be as wild as you will (I have heard Sinn Feiners called Jews!), but, so long as this wretched habit of secrecy is maintained, there is no correcting that judgment. A universal suspicion is engendered and spreads.

Meanwhile the same vice drags into publicity every ill-sounding Jewish act and name and leaves in obscurity the honoured names and useful public actions of Jewry. For a false name, like a forgery, advertises itself.

It is not always recognized in this connection that the Jewish “booms,” which are so fruitful a cause of exasperation, depend on this same policy of concealment and on that account add to the volume of anger as each new trick is discovered.

Not that the objects of these world-wide campaigns are unworthy of attention. The Jewish actor, or film-star, or writer or scientist selected is usually talented; the victim of injustice whose case is advertised on the big drum has often a genuine grievance. But that the notice demanded is out of all proportion and that its dependence on Jewish organization is always kept hidden.

So much for the element of secret action. A great deal more might be written upon it, but there are two reasons against enlarging thereon. First, a full discussion would take up far too much of my space; secondly, it would tend to add what I particularly wish to avoid in these pages, I mean emphasis upon the errors of the Jew. It would continue a quarrel, our whole object in which is to find peace.

2. The Expression of Superiority by the Jew

This is a very different matter. The mere sense of superiority is not something in which any special policy can be recommended, because it is there and cannot be remedied. It is part of the whole position. But it is possible to restrain its expression. For that purpose it is of value to define it, to put it upon record and to estimate its effect upon our issue.

The Jew individually feels himself superior to his non-Jewish contemporary and neighbour of whatever race, and particularly of our race; the Jew feels his nation immeasurably superior to any other human community, and particularly to our modern national communities in Europe.

The frank statement of so simple and fundamental a truth is rarely made. It will sound, I fear, shocking in many ears. To many others it will sound not so much shocking as comic, and to many more stupefying.

The idea that the Jew should think himself our superior is something so incomprehensible to us that we forget the existence of the feeling. If it be constantly reiterated, for the purpose of dealing with this great political difficulty, it is perhaps reluctantly admitted, but still held as sort of abnormal, bewildering truth. I contend that the forgetfulness of that truth, the attempt to solve the problem without that truth remaining constant and fixed in the mind of the statesman, is in a very large measure the cause of our failure in the past; and that the way the Jew openly acts upon it in gesture, tone, manner, social assertion, is a very important factor in the quarrel between his race and ours.

Consider the attitude of statesmanship in the past towards this vital conflict. In every such attitude I think the Jewish conviction of superiority has been omitted.

For the attitudes taken up by European statesmen in the past towards the alien Jewish element in their midst have always been one of three sorts:—

(1) Either they have acted as though there were no Jewish nation, as though the Jew were merely a private citizen like any other who happened to have peculiar opinions and customs of his own but who was not substantially different from the men around him.

(2) Or they have attempted to suppress, or to expel, or to destroy the Jew with ignominy and violence.

(3) Or, while recognizing the existence of the Jewish nation as something separate from their own fellow-nationals whom they have to administrate, the statesmen have tried to arrive at equilibrium by a sort of pact in which Jewish separateness was recognized, but under conditions of disability.

Now in all these three methods there is absent all recognition of the Jewish feeling of superiority.

In the first it is obviously lacking because the whole idea of a Jewish nation is absent. It is equally obviously lacking from the second method, that of persecution: the persecutor instinctively acts as though the Jew felt himself to be an inferior. In the third method it is also absent, not in theory but in practice. For the statesmen who have acted thus in the past have not attempted to give the Jews a separate status only, they have in point of fact nearly always given them an inferior status. By so doing they have exasperated the Jewish national sentiment.

For instance, certain nations have treated Jews as a separate people, as aliens, by forbidding them untrammelled residence, and enforcing registration. But when it came to taxation or freedom from military service, then there was no special recognition of the Jew.

There is indeed a fourth attitude which has occasionally appeared in history when States have been in active decline or have fallen into the hands of base and weak men, and that is the exaggerated flattery and support of a few powerful wealthy Jews by administrators who were bribed or cowed. We are suffering from that to-day. But these exceptional cases (they have always led to national disaster) do not form a true category of Statesmanship in the matter. Nor is there even in those who thus actually advantage a few Jews above their own fellow-citizens, and give them special prominence and power, so much a recognition of the Jewish sense of superiority as a secret hatred of their Jewish masters.

Bitter as is everywhere the secret attack on the Jews by those who have subjected themselves for gain or publicity, it is nowhere so bitter as in the private speech of the politicians.

It would seem in the presence of so many failures in policy, and all these failures having in common the non-recognition of this Jewish feeling, that success can never be obtained unless we fully allow for it. I submit that there will never be peace between any Jewish alien minority and the community within which it may happen to reside until those who administrate that community fully accept, and studiously avoid the exasperation of, this state of the Jewish mind.

In statesmanship, as in every other form of human activity, exact definition is of the first importance. We must distinguish at the outset between this Jewish sense of superiority and any real superiority. The statesman is not concerned with the rightness or wrongness of the Jewish attitude. It may be a most absurd illusion, or it may be a most profound vision. He has nothing to do with that. Having made up his mind that the small and quite alien minority must be tolerated and must be allowed to live as happily as possible in the midst of a community from which it so profoundly differs, his next duty is to know thoroughly the nature of the material upon which he is acting and with which he has to deal.

He may smile at the Jewish sense of superiority; he may even be privately indignant; but he must be quite sure that it is a permanent part of the nation with which he has to settle. It will never be removed. The Jew in the East End of London, the poorest of the poor, feels himself the superior of the magistrate before whom he is hauled, of the policeman who keeps order in the streets, and immensely the superior of the simple-faced soldiers and sailors, whose trade is the most typical of our own race. He even feels himself the superior of those whom he better understands—the negotiators: the people who live by cunning. The expression of our faces, our gesture, our manner; the very fact that our minds, less acute, are also broader, confirms his feeling.

This fixed idea of superiority which appears in every phrase and implication, is taken for granted by the Jew. It is felt, I say, by the poorest and most oppressed, the least rich and the most unfortunate of the Jewish people in our midst. Unfortunately—and this is the crux—it proceeds to unrestrained expression. It is this which is so violently resented. It is this which aggravates the quarrel. It is this which must be kept in control if we are to have peace; not the sense of superiority, that is ineradicable, but the expression of it. It appears, as we all know, with extraordinary emphasis in the action and manner of the few very wealthy Jews with whom the directing classes of the nation are better acquainted. But whether he be a rich man suffering only from alien and hostile surroundings, or a poor man suffering from all the lowering forces of squalor, of destitution and of contempt, the Jew feels himself the potential master of his hosts and shows it. He reposes in the same confidence as was felt by Disraeli when he said: “The Jew cannot be absorbed; it is not possible for a superior race to be absorbed by an inferior.” But unfortunately he does not only repose on that foundation; he also acts upon it, and that is intolerable.

We must, I say, allow for this feeling in any settlement we make; we have also to study its consequences. Otherwise we shall be baffled by phenomena which would seem inexplicable. But we need not allow for—on the contrary, we should actively condemn—an open attitude of Jewish contempt for ourselves.

Here are some consequences of this open expression of superiority—consequences which we all discover to-day in the relations between the Jewish people and ourselves and which are leading us into a situation very dangerous for them and for us.

First, you have that familiar handling of European things by the Jew, which is continually stirring the wrath of the European and as continually leaving the Jew in wonderment what possible harm he can have done. Thus, the Jew will write of our religion, taking for granted that it is folly, and will marvel that we are offended. He will appear in our national discussions, not only giving advice, but attempting to direct policy, and will be puzzled to discover that his indifference to national feeling is annoying. He will postulate the Jewish temperament as something which, if different from ours, must, whether we like it or not, be thrust upon us.

He acts in all these things as every one acts instinctively in the presence of those whom they take for granted to be inferiors, and when men talk of the “Jewish insolence,” or the “Jewish sneer,” they imply that attitude. We are wrong if we take these things as calculated insult. The action of the Jew, in so far as it proceeds from this sense of superiority, is no more calculated and no more deliberately hostile than are our own actions whenever we find ourselves in relations with those whom we think inferior to ourselves. But we are right to point them out, to resent them, to reprove them, and, if it became necessary, to end them.

The Jewish problem will never be solved unless we make allowances for the sense of superiority, take it for granted as an unavoidable evil, and restrain our indignation in its presence; but neither will it be solved if we permit its more and more open expression.

Another consequence of this attitude: The Jew, on account of it, makes no effort to get into touch with the mass of the race in the midst of which he may happen to be living. He is content to remain separate from it, and thinks he cannot help remaining separate from them. And he shows it. He consents to associate with the élite, with those who direct, with those who have some special sort of function, but it seems to him a waste of time to attempt communion with the rest. And he shows it. That is what Renan meant when he said that the Jews were the least democratic of all people. Renan, who was supported by Jewish money and lived, while he was doing his best work, dependent on a Jewish publisher; Renan, who was so fascinated by the history of Israel, and who decided himself to become a scholar in all Hebraic things, understood the Jew not at all. His judgments upon them are invariably superficial and to one side of the truth; the judgments of a foreigner—an admiring foreigner but not a sympathetic foreigner. And when he said that the Jews were not democratic he was, instead of passing a judgment upon an intimate political instinct of the Jewish people, simply noting an external phenomenon. For the Jews are, as a fact, strongly democratic—no nation more so—in their national relations among themselves; they only appear undemocratic to us because they openly look down on us among whom they live.

Another form taken by that open expression of the sense of superiority among the Jews: It lends to all their actions in our State a certain assurance and solidity which vastly strengthens their power of resistance, no doubt, but also provokes their misfortunes. The religious interpreter of history might say that they had been specially endowed with this sense by Providence because Providence intended them to survive as a national unit miraculously, in the face of every disability; to remain themselves for 2,000 years under conditions which would have destroyed any other people in perhaps a century: and yet intended to suffer. The rationalist will say that the expression of a sense of superiority, and the power of resistance that accompanies it are but different names for the same thing; that but for the presence of that expression of superiority the resistance could not have succeeded, but for the resistance there could have been no persecution; that there was no design in the matter, only the chance presence of a particular quality which has produced its necessary and logical effect. But whichever be the true explanation, the historical fact remains, that this sense of superiority produced an open and overweening expression of it whenever the Jews have been free to give vent to their feelings, and that while it has had, as one great consequence, the strengthening of the identity, permanence, survival of the Jewish people, it has also had, for another great consequence, their recurrent oppression following on every period of freedom.

There is one last thing to be said, which it is almost impossible to say without the danger of giving pain and therefore of confusing the problem and making the solution more difficult. But it must be said, because, if we shirk it, the problem is confused the more. It is this: While it is undoubtedly true, and will always be true, that a Jew feels himself the superior of his hosts, it is also true that his hosts feel themselves immeasurably superior to the Jew. We can only arrive at a just and peaceable solution of our difficulties by remembering that the Jew, to whom we have given special and alien status in the Commonwealth, is all the while thinking of himself as our superior. But on his side the Jew must recognize, however unpalatable to him the recognition may be, that those among whom he is living and whose inferiority he takes for granted, on their side regard him as something much less than themselves.

That statement, I know, will be as stupefying to the Jew as its converse is stupefying to us. It will seem as extraordinary, as incredible, and all the rest of it; but it is true, and it is a permanent truth. Unless the Jews recognize that truth the trouble will go on indefinitely. There is no European so mean in fortune or so base in character as not to feel himself altogether the superior of any Jew, however wealthy, however powerful, and (I am afraid I must add) however good. True, virtue has a superiority of its own which cannot be hidden, and the cruel, or the treacherous, or the debauched European cannot but feel himself morally inferior to a Jew who is just, self-governed, merciful, generous, and the rest of it. But we know how it is with national feelings. The type is stronger for us than the individual; and while we may recognize certain superior characteristics in the individual, we are thinking all the while of the race, of the communal form, and contrasting our own with the alien form to the disadvantage of the latter.

So difficult is it for the Jew to appreciate this factor in the problem that his lack of appreciation has been almost as great a cause of difficulty in the past as the same lack upon our side. We seem to him insolent when, in our own eyes, we are merely acting normally as superiors.

What emotion does it not create, I wonder, in some Jewish merchant or money-dealer who has purchased a high directing place in our plutocracy when he discovers from the gesture, the tone, the expression of some chance poor Englishman, perhaps no more than an embarrassed hack writer, a clear feeling of superiority? Must it not seem to him mere insolence? “What possible claim” (he will say within himself) “has this goy, and a poor unsuccessful goy at that, to treat me as though I were less than he! I, who am worth millions, who am ruling and doing what I will with his own national leaders, who dispose of his State very much as I choose, and who belong to that nation which is wholly above all others, the Jewish people?” Everywhere the Jew discovers the consequences of this feeling, even though that feeling be to him so incomprehensible that he can hardly admit its existence.

Well, whether he likes to admit it or not, it is there. Individual Jews may be flattered for the sake of their wealth or because of the fear of them, in which a commercial community stands. Such Jews as mistake the current printed word which they read for the spoken words they never hear may fall into the error of thinking that this sense of superiority on our part did not exist. They must be warned, if ever the problem is to be solved, that it does.

In their case, just as in ours, a right solution can only be arrived at by the frank admission that the feeling is there and by the fixed knowledge that, whether the feeling be an illusion or represent a reality, it will not change; but also by a repression of it in our mutual relations.

We may add to our summary of this subtle but profound cause of disturbance the further truth that a paradox of the sort is to be found, though perhaps less emphasized, in every other political problem. The diplomat resident in a foreign capital has to consider not only his own certitude that his hosts are inferior, but their certitude of their own superiority to him and his. The general in the field may be certain of his mastery over an opponent, but if that opponent is as yet undefeated he will do ill to forget that he is matched by a confidence equal to his own. Still more does the negotiator in commerce act upon this principle and recognize it, or at least if he fails to do so, he invites disaster. For when the commercial man is occupied in overreaching his neighbour, his chances of success very largely depend upon his treating that neighbour as though he really were what he believes himself to be. He may be dealing with a stupid and vain man easily to be overmatched and impoverished, but if he lets it appear that he regards his proposed victim as a vain and stupid man, then he will miss his bargain.

In general, there is no success over others, nor even (which is much more necessary), any permanent arrangement possible with others, unless we know, allow for, and act upon the self-judgment of others, however wrong we may believe that self-judgment to be.

It is clear that in this conflict between the Jew and, let us say, the European (for it is between the Jew and the white Occidental race that our present problem lies, though the same problem arises with all other races among whom the Jew may find himself), both parties cannot be right. A being superior to the race of man and looking on our petty quarrels might be able to decide which of the two opponents were nearer reality, and whether we are the better justified in our contempt of the Jew or the Jew in his contempt of us. But in working out our own solution without the aid of such guidance, there is no rule but for both parties to take for granted what each regards as an illusion in the other; to restrain its expression for the sake of reaching a settlement; and in the settlement they arrive at, to admit as a factor necessarily and permanently present what each still secretly regards as a folly, but an incurable folly, in the other.

The alternative to such self-restraint is a falling back into the old circle of submission, consequent anger accompanied by shame and violence, and these followed by remorse.

(Continue to Chapter 6: The Cause of Friction Upon Our Side)