Editor’s note: The following is extracted from An Introduction to the History of Western Europe, by James Harvey Robinson (published 1902).

Position of Henry V

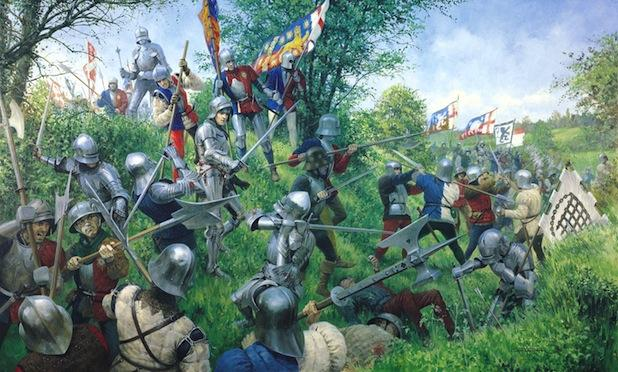

Agincourt, 1415

Henry V had no real basis for his claim to the French crown. Edward III had gone to war because France was encroaching upon Guienne and aiding Scotland, and because he was encouraged by the Flemish towns. Henry V, on the other hand, was merely anxious to make himself and his house popular by deeds of valor. Nevertheless his very first victory, the battle of Agincourt, was as brilliant as that of Crécy or Poitiers. Once more the English bowmen slaughtered great numbers of French knights. The English then proceeded to conquer Normandy and march upon Paris.

Treaty of Troyes, 1420

Burgundians and Orleanists were upon the point of forgetting their animosities in their common fear of the English, when the duke of Burgundy, as he was kneeling to kiss the hand of his future sovereign, the Dauphin, was treacherously attacked and killed by a band of his enemies. His son, the new duke of Burgundy, Philip the Good, immediately joined the English against the Dauphin, whom he believed to be responsible for his father’s murder. Henry then forced the French to sign the treaty of Troyes (1420), which provided that he was to become king of France upon the death of the mad Charles VI.

Henry VI recognized as king in northern France

Both Henry V and Charles VI died two years later. Henry V’s son, Henry VI, was but nine months old; nevertheless according to the terms of the treaty of Troyes he succeeded to the throne in France as well as in England. The child was recognized only in a portion of northern France. Through the ability of his uncle, the duke of Bedford, his interests were defended with such good effect that the English succeeded in a few years in conquering all of France north of the Loire, although the south continued to be held by Charles VII, the son of Charles VI.

Joan of Arc

Charles VII had not yet been crowned and so was still called the Dauphin even by his supporters. Weak and indolent, he did nothing to stem the tide of English victories or restore the courage and arouse the patriotism of his distressed subjects. This great task was reserved for a young peasant girl from a remote village on the eastern border of France. To her family and her companions Joan of Arc seemed only “a good girl, simple and pleasant in her ways,” but she brooded much over the disasters that had overtaken her country, and a “great pity on the fair realm of France” filled her heart. She saw visions and heard voices that bade her go forth to the help of the king and lead him to Rheims to be crowned.

Relief of Orleans by Joan, 1429

It was with the greatest difficulty that she got anybody to believe in her mission or to help her to get an audience with the Dauphin. But her own firm faith in her divine guidance triumphed over all doubts and obstacles. She was at last accepted as a God-sent champion and placed at the head of some troops despatched to the relief of Orleans. This city, which was the key to southern France, had been besieged by the English for some months and was on the point of surrender. Joan, who rode on horseback at the head of her troops, clothed in armor like a man, had now become the idol of the soldiers and of the people. Under the guidance and inspiration of her indomitable courage, sound sense, and burning enthusiasm, Orleans was relieved and the English completely routed. The Maid of Orleans, as she was henceforth called, was now free to conduct the Dauphin to Rheims, where he was crowned in the cathedral (July 17, 1429).

Execution of Joan, 1431

The Maid now felt that her mission was accomplished and begged permission to return to her home and her brothers and sisters. To this the king would not consent, and she continued to fight his battles with undiminished loyalty. But the other leaders were jealous of her, and even her friends, the soldiers, were sensitive to the taunt of being led by a woman. During the defense of Compiègne in May, 1430, she was allowed to fall into the hands of the duke of Burgundy, who sold her to the English. They were not satisfied with simply holding as prisoner that strange maiden who had so discomfited them; they wished to discredit everything that she had done, and so declared, and undoubtedly believed, that she was a witch who had been helped by the Evil One. She was tried by a court of ecclesiastics, found guilty of heresy, and burned at Rouen in 1431. Her bravery and noble constancy affected even her executioners, and an English soldier who had come to triumph over her death was heard to exclaim: “We are lost—we have burned a saint.” The English cause in France was indeed lost, for her spirit and example had given new courage and vigor to the French armies.

England loses her French possessions

End of the Hundred Years’ War, 1453

The English Parliament became more and more reluctant to grant funds when there were no more victories gained. Bedford, through whose ability the English cause had hitherto been maintained, died in 1435, and Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, renounced his alliance with the English and joined Charles VII. Owing to his acquisition of the Netherlands, the possessions of Philip were now so great that he might well be regarded as a European potentate whose alliance with France rendered further efforts on England’s part hopeless. From this time on the English lost ground steadily. They were expelled from Normandy in 1450. Three years later, the last vestige of their long domination in southern France passed into the hands of the French king. The Hundred Years’ War was over, and although England still retained Calais, the great question whether she should extend her sway upon the continent was finally settled.

The Wars of the Roses between the houses of Lancaster and York, 1455–1485

The close of the Hundred Years’ War was followed in England by the Wars of the Roses, between the rival houses which were struggling for the crown. The badge of the house of Lancaster, to which Henry VI belonged, was a red rose, and that of the duke of York, who proposed to push him off his throne, was a white one. Each party was supported by a group of the wealthy and powerful nobles whose rivalries, conspiracies, treasons, murders, and executions fill the annals of England during the period which we have been discussing. Vast estates had come into the hands of the higher nobility by inheritance, and marriages with wealthy heiresses. Many of the dukes and earls were related to the royal family and consequently were inevitably drawn into the dynastic struggles.

Retainers

The nobles no longer owed their power to vassals who were bound to follow them to war. Like the king, they relied upon hired soldiers. It was easy to find plenty of restless fellows who were willing to become the retainers of a nobleman if he would agree to clothe them with his livery and keep open house, where they might eat and drink their fill. Their master was to help them when they got into trouble, and they on their part were expected to intimidate, misuse, and even murder at need those who opposed the interests of their chief. When the French war was over, the unruly elements of society poured back across the Channel and, as retainers of the rival lords, became the terror of the country. They bullied judges and juries, and helped the nobles to control the selection of those who were sent to Parliament.

Edward IV secures the crown

It is needless to speak of the several battles and the many skirmishes of the miserable Wars of the Roses. These lasted from 1455, when the duke of York set seriously to work to displace the weak-minded Lancastrian king, Henry VI, until the accession of Henry VII, of the house of Tudor, thirty years later. After several battles the Yorkist leader, Edward IV, assumed the crown in 1461 and was recognized by Parliament, which declared Henry VI and the two preceding Lancastrian kings usurpers. Edward was a vigorous monarch and maintained his own until his death in 1483.

Edward V, 1483; Richard III, 1483–1485

Death of Richard in the battle of Bosworth Field

Accession of Henry VII of the house of Tudor, 1485

End of the Wars of the Roses

Edward’s son, Edward V, was only a little boy, so that the government fell into the hands of the young king’s uncle, Richard, Duke of Gloucester. The temptation to make himself king was too great to be resisted, and Richard soon seized the crown. Both the sons of Edward IV were killed in the Tower of London, and with the knowledge of their uncle, as it was commonly believed. This murder made Richard unpopular even at a time when one could kill one’s political rivals without incurring general opprobrium. A new aspirant to the throne organized a conspiracy. Richard III was defeated and slain in the battle of Bosworth Field in 1485, and the crown which had fallen from his head was placed upon that of the first Tudor king, Henry VII. The latter had no particular right to it, although he was descended from Edward III through his mother. He hastened to procure the recognition of Parliament, and married Edward IV’s daughter, thus blending the red and white roses in the Tudor badge.

The despotism of the Tudors

The Wars of the Roses had important results. Nearly all the powerful families of England had been drawn into the fierce struggles, and a great part of the nobility, whom the kings had formerly feared, had perished on the battlefield or lost their heads in the ruthless executions carried out by each party after it gained a victory. This left the king far more powerful than ever before. He could now dominate Parliament, if he could not dispense with it. For a century and more the Tudor kings enjoyed almost despotic power. England ceased for a time to enjoy the free government for which the foundations had been laid under the Edwards and the Lancastrian kings, whose embarrassments at home and abroad had made them constantly dependent upon the aid of the nation.

France establishes a standing army, 1439

In France the closing years of the Hundred Years’ War had witnessed a great increase of the king’s power through the establishment of a well-organized standing army. The feudal army had long since disappeared. Even before the opening of the war the nobles had begun to be paid for their military services and no longer furnished troops as a condition of holding fiefs. But the companies of soldiers, although nominally under the command of royal officers, were often really independent of the king. They found their pay very uncertain, and plundered their countrymen as well as the enemy. As the war drew to a close, the lawless troopers became a terrible scourge to the country and were known as flayers, on account of the horrible way in which they tortured the peasants in the hope of extracting money from them. In 1439 the Estates General approved a plan devised by the king, for putting an end to this evil. Thereafter no one was to raise a company without the permission of the king, who was to name the captains and fix the number of the soldiers and the character of their arms.

The permanent tax fatal to the powers of the Estates General

The Estates agreed that the king should use a certain tax, called the taille, to support the troops necessary for the protection of the frontier. This was a fatal concession, for the king now had an army and the right to collect what he chose to consider a permanent tax, the amount of which he later greatly increased; he was not dependent, as was the English king, upon the grants made for brief periods by the representatives of the nation.

The new feudalism

Before the king of France could hope to establish a compact, well-organized state it was necessary for him to reduce the power of his vassals, some of whom were almost his equals in strength. The older feudal dynasties, as we have seen, had many of them succumbed to the attacks and the diplomacy of the kings of the thirteenth century, especially of St. Louis. But he and his successors had raised up fresh rivals by granting whole provinces, called appanages, to their younger sons. In this way new and powerful lines of feudal nobles were established, such, for example, as the houses of Orleans, Anjou, Bourbon, and, above all, of Burgundy. The accompanying map shows the region immediately subject to the king—the royal domain—at the time of the expulsion of the English. It clearly indicates what still remained to be done in order to free France from feudalism and make it a great nation. The process of reducing the prerogatives of the nobles had been begun. They had been forbidden to coin money, to maintain armies, and to tax their subjects, and the powers of the king’s judges had been extended over all the realm. But the task of consolidating France was reserved for the son of Charles VII, the shrewd and treacherous Louis XI (1461–1483).

Extent of the Burgundian possessions in the fifteenth century

By far the most dangerous of Louis’ vassals were Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy (1419–1467), and his impetuous son, Charles the Bold (1467–1477). Just a century before Louis XI came to the throne, the old line of Burgundian dukes had died out, and in 1363 the same King John whom the English captured and carried off to England, presented Burgundy to his younger son Philip. By fortunate marriages and lucky windfalls the dukes of Burgundy had added a number of important fiefs to their original possessions, and Philip the Good ruled over Franche-Comté, Luxembourg, Flanders, Artois, Brabant, and other provinces and towns which lie in what is now Holland and Belgium.

Ambition of Charles the Bold, 1467–1477

Charles the Bold busied himself for some years before his father’s death in forming alliances with the other powerful French vassals and conspiring against Louis. Upon becoming duke himself he set his heart upon two things. He resolved, first, to conquer Lorraine, which divided his territories into two parts and made it difficult to pass from Franche-Comté to Luxembourg. In the second place, he proposed to have himself crowned king of the territories which his forefathers had accumulated and in this way establish a strong new state between France and Germany.

Charles defeated by the Swiss at Granson and Murten, 1476

Naturally neither the king of France nor the emperor sympathized with Charles’ ambitions. Louis taxed his exceptional ingenuity in frustrating his aspiring vassal; and the emperor refused to crown Charles as king when he appeared at Trier eager for the ceremony. The most humiliating, however, of the defeats which Charles encountered came from an unexpected quarter. He attempted to chastise his neighbors the Swiss for siding with his enemies and was soundly beaten by that brave people in two memorable battles.

Death of Charles, 1477

Marriage of Mary of Burgundy to Maximilian of Austria

The next year Charles fell ingloriously in an attempt to take the town of Nancy. His lands went to his daughter Mary, who was immediately married to the emperor’s son, Maximilian, much to the disgust of Louis, who had already seized the duchy of Burgundy and hoped to gain still more. The great importance of this marriage, which resulted in bringing the Netherlands into the hands of Austria, will be seen when we come to consider Charles V (the grandson of Mary and Maximilian) and his vast empire.

Work of Louis XI

Louis XI did far more for the French monarchy than check his chief vassal and reclaim a part of the Burgundian territory. He had himself made heir to a number of provinces in central and southern France,—Anjou, Maine, Provence, etc.,—which by the death of their possessors came under the king’s immediate control (1481). He humiliated in various ways the vassals who in his early days had combined with Charles the Bold against him. The duke of Alençon he imprisoned; the rebellious duke of Nemours he caused to be executed in the most cruel manner. Louis’ political aims were worthy, but his means were generally despicable. It sometimes seemed as if he gloried in being the most rascally among rascals, the most treacherous among the traitors whom he so artfully circumvented in the interests of the French monarchy.

England and France establish strong national governments

Both England and France emerged from the troubles and desolations of the Hundred Years’ War stronger than ever before. In both countries the kings had overcome the menace of feudalism by destroying the power of the great families. The royal government was becoming constantly more powerful. Commerce and industry increased the national wealth and supplied the monarchs with the revenue necessary to maintain government officials and a sufficient armed force to execute the laws and keep order throughout their realms. They were no longer forced to rely upon the uncertain pledges of their vassals. In short, the French and the English were both becoming nations, each with a strong national feeling and a king whom every one, both high and low, recognized and obeyed as the head of the government.

> (Contined from Part 1)

Is this intended to be a link to the first part? Does not link.

Thanks. I will go fix it.

Mr. Mantel,

Have you also read The New Cambridge Medieval History? Checking if you have any thoughts between the quality of the quoted volume and that one. Need to add to my own collection, as yours has started to inspire me once more.

I’ve heard of that book but not read it. Sounds like something I should add to my library as well.