Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Hero Tales From American Life, by Francis Trevelyan Miller (published 1909).

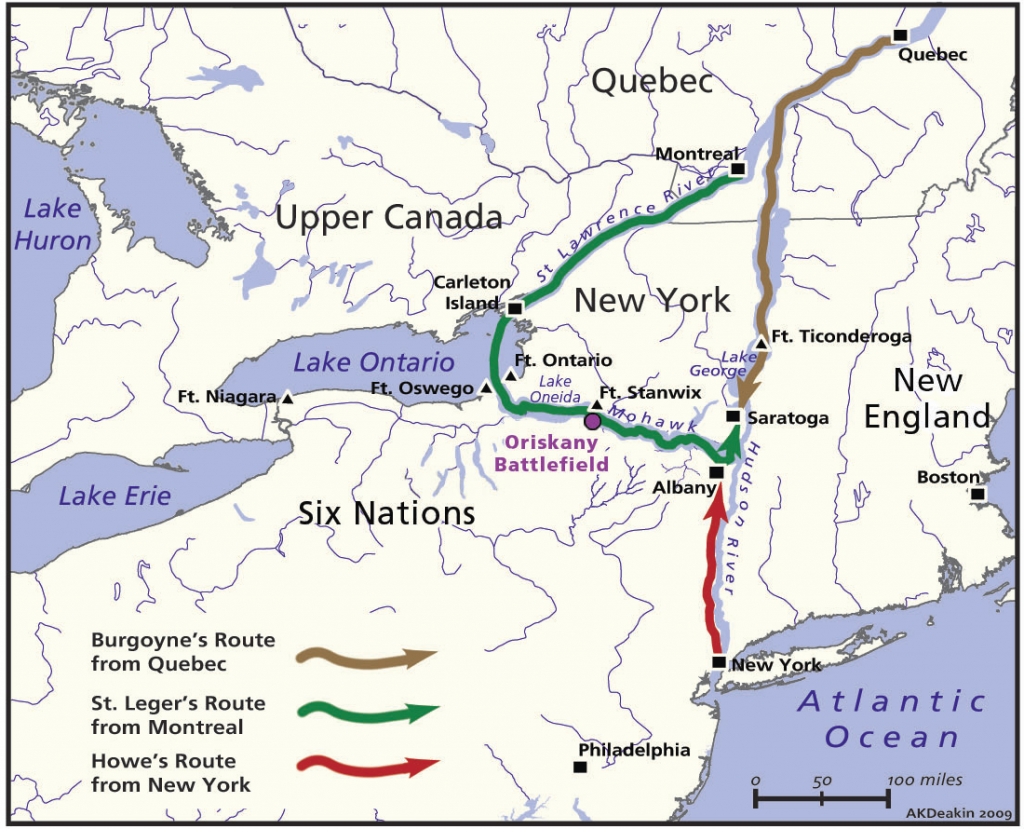

It was in the Mohawk Valley, back in 1777. The Tories and Indians were devastating the homes of the American patriots. Down the valley swept St. Leger, with his strange army under the British flag, loyalist Tory and aborigine — 1,500 strong — to join forces with General Burgoyne, who was on his way down the Hudson from the northern lake region, cutting the colonial forces in halves so that each division could be fought separately and forced to surrender. A brilliant plan of warfare had been conceived.

It was the sixth day of August. The Americans, who had been rallied from the farms, with a few militia men, half-trained and poorly armed, were gathered under the command of General Nicholas Herkimer, a quaint Dutch-American[1], who some years before had fought himself under a British ensign against the French and Indians. As they moved down the valley, they heard the rumors of massacres, and that the British were offering the Indians twenty-five dollars for every scalp of an American patriot that they could bring into camp, regardless of age or sex.

The brave patriot farmers reached Whitesboro. A courier hurried to Fort Stanwix to notify its commander, Peter Gansevoort, of their approach and to summon his garrison to their relief.

“Fire your cannon three times,” said the message, “to inform us when your garrison starts.”

The rumors of massacre lay heavily upon the mind of old General Herkimer. As he moved his men slowly down the valley, a friendly Indian brought him the warning that an ambush had been prepared ahead. He therefore called a halt. His younger lieutenants were impatient at their commander’s conservatism, and intimated in their anger that he might still be friendly to the British King.

The old warrior, who spoke broken English, was seized with rage.

“The blood be on your own heads, then,” he shouted, in hardly intelligible English. “Vorwaerts.”[2]

And on to the attack the column marched, without waiting for the three cannon shots from the fort, until they were two miles west of Oriskany and passing through a ravine. The advance guard was moving along without scouts. Suddenly, from both sides came the awful war-cry of the Indians, and a deadly fire from rifles. In front, a force of red-coated British regulars were massed on the firing line. The American militia men fell back. The assault was one of the most atrocious in the annals of warfare, the patriots being scalped as they took refuge behind the logs and trees. The rear guard was cut off and with it the supply train and the food.

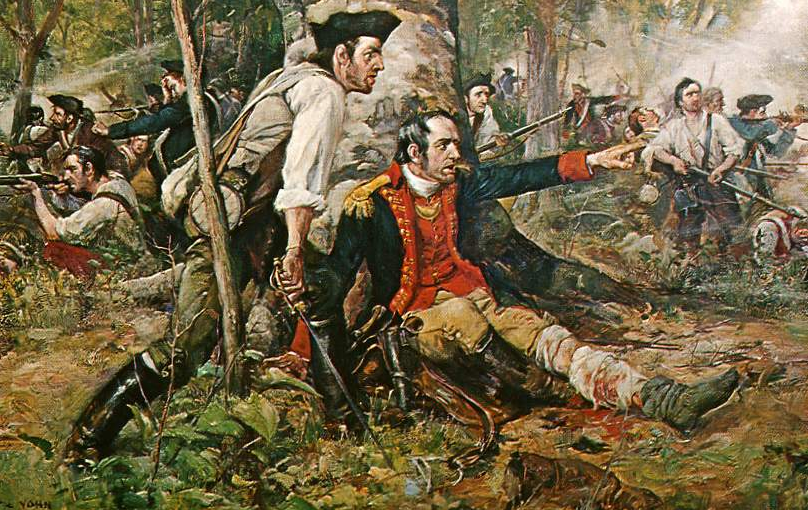

After the manner of men of iron-will and courage, old Nicholas Herkimer rallied a few straggling men, and stormed the hills occupied by the proud British rangers. A shot from a rifle went through the general’s leg and his horse fell from under him, but the serenity of the old general was undisturbed. He ordered the saddle taken off his horse and placed against a tree. Seated there, he calmly lit his old black clay-pipe — and went on directing the battle.

The Americans now took to the trees and other positions of advantage, and opened warfare in true Indian fashion. The Indians, in their savage hunt for scalps, molested only those who were within easy reach. The Tories came hurrying on from the village, eager for the fray, and the sight of their neighbors in the guise of enemies aroused them into greater fury. Then, mingling with the yell of the savages, and the shrieks of the massacred, came the sound of three cannon shots, the signal for the advance of the garrison from the fort!

But old Herkimer still sat beneath his tree, calmly smoking. Watching the battle as best he could from his post, he witnessed the varying fortunes of that awful combat; directing assistance first to one part, then to another. Grim, determined, sputtering in his native German and again in English, hard to understand, he gave his orders with composure and courage. One of the young American officers, who had forced the battle, was dead; another was desperately wounded.

“Your wound, General?” inquired a young officer, coming up for orders.

“Ach, ‘s ist nichts,” he growled, and, then remembering that his aid could not understand, he shouted, “Notting, I tell you; yust notting!”

Then pulling away at his pipe, he ordered: “I mean take dat lot of fellows from behind dat rock dere and order dem up on de right vere dem red coats is making such troubles for ’em.”

But the gathering lines in the old general’s face told their own sad story. The wound in his leg was slowly sapping his life away. For six hours the brave old man sat there beneath his tree on his saddle, cheering on the stricken forces.

A shout went up from the battlefield. The smoke cleared away. Over the hills the Indians and Tories were fleeing in terror. The Americans held the field. St. Leger, and his warfare of horror against women and babies was meeting his first stubborn resistance.

“Thank Got,” muttered the iron-hearted Nicholas Herkimer, as he was carefully lifted by his soldiers and carried to his home, thirty-five miles away.

“Your leg must be amputated,” remarked the surgeon.

It was before the days of modern anesthesia for lessening pain. The old general called for his pipe and puffed great clouds of gray smoke as the wounded leg was removed. Ten days later, a hemorrhage issued from the unhealed limb. The old warrior had seen death too often to fear it among his family and friends. As his life ebbed away, he gathered his beloved ones about him and called for the family Bible. Opening it, he turned to the thirty-eighth psalm:

“O Lord, rebuke me not in thy wrath, neither chasten me in thy hot displeasure — for mine iniquities are gone over my head; as an heavy burden they are too heavy for me — I am feeble and sore-broken — Lord, all my desire is before thee and my groaning is not hid from thee; my heart panteth, my strength.”

The voice grew slower, weakened, and then ceased. Nicholas Herkimer was with the greater army in the beyond — the soldiers of eternity. On the ground where he fought so valiantly for liberty, now stands his monument. There he sits in bronze, pipe in hand, his right arm stretched out in command, pointing the way to victory as he did on that memorable day in 1777.

__________________________

[1] Though New York (formerly New Netherland) began as a Dutch colony, Herkimer himself was the son of Palatine German immigrants. (ed.)

[2] Forward!

Hadn’t heard of Herkimer. His folks came from Leimen, Rheinland-Pfalz, not too far from where I was born.