Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Makers and Romance of Alabama History, by B. F. Riley (published 1914).

The heroism of Alabama manhood was never more essentially embodied than it was in the career and character of the gallant young soldier, John Pelham. His name was repeatedly mentioned on the lips of the Confederate chieftains as “the gallant Pelham.” By no other name was he so generally known in the great galaxy of heroes in the Army of Northern Virginia. Pelham was especially admired by Generals Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson and J. E. B. Stuart. A prodigy of valor, he enjoyed the admiration of the entire army.

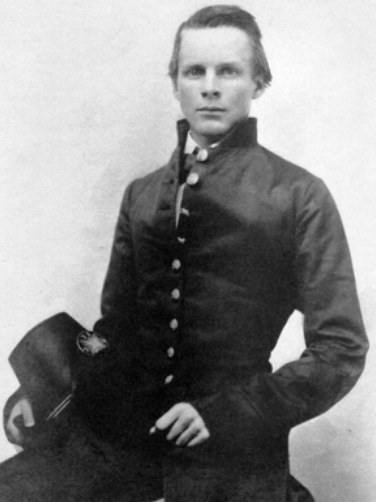

The Civil War found Pelham a cadet at West Point. He was then about twenty-two years old. He was not specially gifted in his textbooks, but his work as a student was solid and substantial. Just before he would have received his diploma he quit the military academy, early in 1861, and started southward. The country throughout was feverish with excitement, and everyone going toward the South was eyed with suspicion, which made it difficult to get through the lines. By the employment of stratagem, Pelham was enabled to slip through the lines at Louisville, professing to be a secret scout of General Scott.

Making his way to Montgomery in April, 1861, that city then being the capital of the new Confederacy, Pelham tendered his services to Honorable Leroy Pope Walker, secretary of war, and was at once given a commission as first lieutenant of artillery in the regular army, and promptly assigned to duty at Lynchburg, Va. His efficiency was at once recognized, and he was transferred to Imboden’s battery, at Winchester, where he was assigned to duty as drillmaster.

Pelham’s first taste of war was at the first battle of Manassas, where his skill was so conspicuous and his courage was so daring as to attract the attention and admiration of the commanders of the army. This was followed by a commission to raise a battery of six pieces of horse artillery, which he proceeded to do during the months immediately following the July in which the first great battle of the war was fought. His battery was rapidly gotten into admirable shape, and he was soon ready for effective service.

The battle of Williamsburg afforded him the first opportunity of engaging the men of his new command. Pelham was so cool and skillful in the fiercest parts of the battle that he excited the wonder of his superiors. With a steadiness unshaken by the thunders of battle, he directed his guns with unerring skill, and no insignificant share of the glory was his as he steadfastly held the enemy at bay. Again at Cold Harbor he displayed so much tactical force combined with accuracy and effectiveness that General Stonewall Jackson grasped the youthful commander by the hand and told him of his high appreciation of the service rendered. At Cold Harbor he engaged three batteries of the enemy with a single Napoleon, and throughout the entire day stubbornly held his position, dealing destruction and death to the enemy. Shortly after the battle of Cold Harbor Pelham’s battery engaged a gunboat at the “White House” and compelled it to withdraw.

By this time, Pelham had gained the reputation of a famous boy fighter, and his steadiness in battle would have done credit to a seasoned veteran. His battery became famous, was the subject of general comment in army circles, and the commanders came to lean on the young officer as one of the indispensable adjuncts to the entire command. In a crisis, or at a difficult juncture, young Pelham was thought of as one to meet it.

When the second battle of Manassas opened, Pelham appeared on the field with his guns, rode to the front as though no danger was imminent, coolly placed his battery astonishingly near the lines of the enemy, and while the enemy rained destruction in that quarter, he took time to get well into position, and at once began with fatal effect on the lines of the foe. Here he won new laurels, and in the accounts of the battle his name was mentioned among those of the general commanders. A second time, Pelham was congratulated by General Stonewall Jackson, who in person thanked him for his skill and bravery.

At the battle of Sharpsburg Pelham was stationed on the left of the Confederate forces, where most of the artillery fell under his immediate command, and the havoc wrought by his guns was fearful. Again at Shepherdstown there was a repetition of the same spirit which he had exhibited on all other occasions. Accompanying Stuart on this memorable march from Aldie to Markham’s, Pelham was compelled to fight against formidable odds along the line of march, and at one point he kept up his firing till the enemy was within a few paces of his piece, when he doggedly withdrew only a short distance, secured a better position for his guns, and resumed his firing in a cool, businesslike way.

It was at Fredricksburg that Pelham was more conspicuous than in any other battle. With a single gun he went to the base of the heights and opened the fight with the same indifference with which he would have gone on the drill ground for a parade. His astonishing intrepidity won the attention of both armies, and Pelham at once became a common target to the batteries of the enemy. He was fearfully exposed, and every moment was filled with extreme hazard, but with an indifference which was sublime he kept up his firing and made fearful inroads on the enemy. It was here that there was evoked from General Lee the expression which has become historic. Observing the brave youth from an eminence, as he kept steadily at his destructive work while shells were bursting about him, General Lee said: “It is glorious to see such courage in one so young.” Without wavering, Pelham held his position at the base of the ridge till his ammunition was gone and he was forced to retire by a peremptory order. Assigned to the command of the artillery on the right, he was throughout the day in the thickest of the fray, and won from General Lee the designation: “The gallant Pelham.” For his gallantry on this occasion Pelham was promoted from a majorship to a lieutenant colonelcy, but was killed before his commission was confirmed by the Confederate Senate.

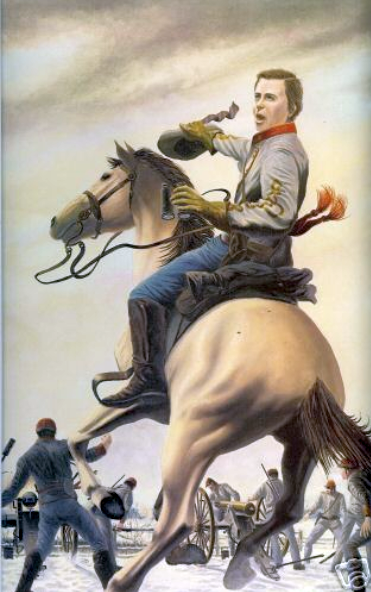

On March 17, 1863, he was visiting some friends at night, in Culpeper County, when the booming of guns at Kelly’s Ford fell on his ear. Excusing himself, he mounted his horse and rode rapidly to the scene of action. His own command had not yet arrived, but he found a regiment wavering in confusion. Spurring his horse quickly to the front of the confused mass, his cool ringing voice restored order, and, placing himself at their head to lead them to battle, a fragment of shell struck the brave youth in the head, and he was instantly killed. The news of the death of Pelham occasioned as much mourning in the army and throughout the Confederacy as there would have been had one of the great general chieftains fallen. Boy as he was, his fame had become proverbial. His body was sent home for burial, and his ashes repose today at Jacksonville, in his native county, Calhoun.

4.5