Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Europe in the Middle Ages, by I. L. Plunket (published 1922). All spelling in the original.

The chief Mahometan Emir during this period of conquest was a certain Orkhan, the son of Othman, whose name in the form ‘Ottoman’ is still borne by his branch of the Turkish race. This Orkhan was quite as cruel and unscrupulous as the Paleologi, but far more statesmanlike; for as he conquered the territory of Greek Emperors and rival Emirs in Asia Minor he consolidated his rule over them by a just and careful government that gradually welded them into a compact state.

When a civil war broke out between John V, the grandson of Andronicus II, and his guardian and co-ruler, a wily schemer of the Michael Paleologus type called John Cantacuzenus, the latter, with utter lack of patriotism, appealed to Orkhan for aid. He even offered him his daughter in marriage, an alliance to which the Turk eagerly agreed, dispatching a large force of auxiliaries to Thrace as token of his friendly intentions towards his future father-in-law. These troops he determined should remain, and difficult indeed the Christians found it to dislodge them in later years, for the Turkish legions had been stiffened by a device of Orkhan which has done more to keep his name in men’s minds perhaps than any of his victories.

It was the Emir’s custom on a march of conquest not to oppress the conquered, but to exact from them a tribute both in money and in child life. From every village that passed under the rule of Orkhan his soldiers carried away from their homes a fixed number of young boys, chosen because of their health and sturdy, well-developed limbs. These children were placed in barracks, where they were educated without any knowledge of their former life to become soldiers of the Prophet—fanatical, highly disciplined, skilled with the bow and sabre, inculcated with but one ideal and ambition—to excel in statecraft or on the battle-field.

Because of their excessive loyalty emirs would choose from among the ranks of these ‘tribute children’ their viziers and other chief officials, while the majority would enter the infantry corps of ‘Janissaries’, or ‘new soldiers’, whose ferocity and endurance in attacking or holding apparently impossible positions became the terror of Europe. In the words of a modern historian, ‘With diabolical ingenuity the Turks secured the victory of the Crescent by the Children of the Cross, and trained up Christian boys to destroy the independence and authority of their country and their Church.’

In 1361, some years after Orkhan’s death, the Turks captured Adrianople, and thus came into contact with other Christian nations besides the Greeks, namely, the Serbians and Hungarians.

The Serbians were the principal Slav race in the Balkans, and under their great ruler Stephen Dushan it had seemed likely that they might become the predominant power in Eastern Europe. The Kings of Bulgaria and Bosnia were their vassals; they had made conquests both in Albania and Greece, thus opening up a way to the Adriatic and Aegean Seas. It would have been well for Christendom if this energetic race of fighters could have subdued the feeble Greeks, and so presented to the Turks, when they crossed the Bosporus, a foe worthy to match the Janissaries in stubborn courage. Unfortunately Stephen Dushan died before the years of Turkish invasion, leaving his throne to a young son, ‘a youth of great parts,’ as a Serbian chronicler describes him, ‘quiet and gracious, but without experience.’

Only experience or an iron will could have held together in those rough times a kingdom relying for its protection on the swords of a quarrelsome nobility; and Serbia broke up into a number of small principalities, her disintegration assisted by the ambitious jealousy of Louis the Great of Hungary, who lost no opportunity of dismembering and weakening this sister kingdom that might otherwise prove a hindrance to his own imperial projects.

With the career of Louis we have dealt in other chapters, and have seen him humbling the Venetians, driving Joanna I out of Naples, acquiring the throne of Poland, fighting against the Turks and the Emperor Charles IV. Because he spent his energy recklessly on all these projects, Louis remains for posterity, apart from the civilizing influence of his court life, one of the arch-destroyers of the Middle Ages, the sovereign who more than any other exposed Eastern Europe to Mahometan conquest. Had he either refrained from his constant policy of aggression towards Serbia, thus allowing her to unite her subject princes in the face of the invading Turks, or had he even been powerful enough to found an Empire of Hungary that would absorb both Serbia and Constantinople and act as a bulwark in the East, mediaeval history would have closed on a different scene. Instead, the famous victories of Louis over the Turks, that made his name honoured by Christendom, were rendered of no avail by other partial victories over Christian nations who should have been his allies.

Battle of Kossovo

On the field of Kossovo, in 1389, the Serbians, shorn of half their provinces and weakened and betrayed by the Hungarians, met the Turks in battle. Both sides have left record of the ferocity of the struggle. ‘The angels in Heaven’, said the Turks, ‘amazed by the hideous noise, forgot the heavenly hymns with which they always glorify God.’ ‘The battle-field became like a tulip-bed with its ruddy severed heads and rolling turbans.’ ‘Few’, wrote the Serbian chronicler, ‘returned to their own country.’

When the day closed, both the Serbian king, Lazar, and the Turkish sultan lay dead amid their warriors, and the victory, as far as the actual fighting was concerned, seemed to rest neither with Christian nor Moslem. Yet, in truth, the Turk could supply other armies, as numerous and as well-equipped, to take the place of those who had fallen, while the Serbians had exhausted their uttermost effort: thus the fruits of the battle fell entirely into the hands of the infidel.

‘Things are hard for us, hard since Kossovo,’ is a modern Serbian saying, for the Serbs have never forgotten the day when they fought their last despairing battle as champions of the Cross, and lost for a time their ambition of dominating Eastern Europe.

From the day of Kossovo the ultimate conquest of Eastern Europe by the Turks became a certainty. Lack of ambition on the part of some of the sultans and a life and death struggle in which others found themselves involved in Asia Minor against Tartar tribes merely deferred the time of reckoning, but it came at last in the middle of the fifteenth century, when Mohammed II, ‘the Conqueror’, determined to reign in Constantinople.

This Mohammed, famous in mediaeval history, was the son of a Serbian princess, and he is said to have grown up indifferent alike to Christianity or Islam. He is described as having ‘a pair of red and white cheeks full and round, a hooked nose, and a resolute mouth’, while flatterers went still farther and declared that his moustache was ‘like leaves over two rosebuds, and every hair of his beard a thread of gold’. In character, from a fierce, undisciplined boy he grew into a self-willed man, intent upon the satisfaction of his ambitions and desires. He could speak, or at least understand, Arabic, Greek, Persian, Hebrew, and Latin; and chroniclers record that it was in reading the triumphs of Alexander and Julius Caesar that he was first inspired with the thought of becoming a great general.

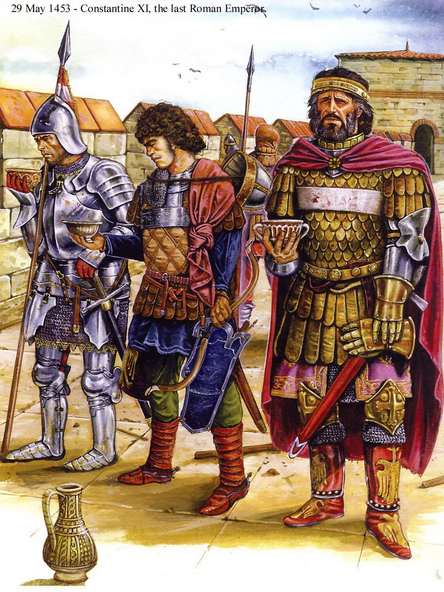

His rival, Constantine XI, the last and best of the Paleologi, was a man of very different type from the Turk, or indeed from his own ancestors. He was devoted to the Christian religion and Greece—brave, simple, and generous. When he first became aware of Mohammed’s aggressive hostility he attempted to disarm it by liberating Turkish prisoners. ‘If it shall please God to soften your heart’, he sent word, ‘I shall rejoice; but however that may be, I shall live and die in the defence of my people and of my Faith.’ His words were put to the test when, in the autumn of 1452, the siege of Constantinople began.

Fall of Constantinople

The Emperor looked despairingly for Western aid, in order to secure which the Emperor John V had himself in years gone by visited Rome and made formal renunciation to the Pope of all the views of the Greek Church that disagreed with Catholic doctrine. One of the chief points of controversy had been the Catholic use of unleavened bread in the Sacrament of the Mass; another, the words of the Nicene Creed, declaring that the Holy Ghost ‘proceeded’ from the Son as well as from the Father.

In all matters of faith as well as of ecclesiastical jurisdiction John V, and later Constantine himself, had made open acknowledgement of the supremacy of Rome, but their compliance did not avail to save their kingdom in the hour of danger: indeed, while it evoked little military support from Catholic nations it aroused keen hostility and treachery at home. There were many Greeks who refused to endorse their sovereign’s signature to what they considered an act of national betrayal, some declaring openly that the Mahometan victories were God’s punishment on kings who had forsaken the faith of their fathers, and that it would be better to see the turbans of the infidels in St. Sophia than a cardinal’s red hat.

When, then, Mohammed began to thunder with his fourteen batteries against the once impregnable walls of Constantinople, making enormous breaches, the reduction of the city had become only a question of days. It is said that the Sultan in his eagerness to take possession offered the Emperor and his army freedom and religious toleration if they would capitulate. ‘I desire either my throne or a grave,’ replied Constantine, knowing well which of the two must be his fate.

Beside some four thousand of his own subjects he could command only a few hundred mercenaries sent by the Pope, and three hundred Genoese. Of the Venetians and other Western Europeans there were even less; and it was with this miniature army that he manned the wide circuit of the walls, led out sorties, and rebuilt as well as he could the gaps made by the heavy guns.

The contest was absurdly unequal, for Mohammed had some two hundred and fifty-eight thousand men; and in May 1453 the inevitable end came to a heroic struggle. Up through the breaches in the wall, that no labour was left to repair, climbed wave after wave of fanatical Janissaries, shouting their hopes of victory and Paradise. Beneath their continuous onslaughts the defenders weakened and broke, fighting to the last amid the narrow streets, until Constantine himself was slain, his body only recognized later by the golden eagles embroidered on his shoes.

The women, and many of the Greeks who had refused to help in this time of crisis because of the Emperor’s submission to the Catholic Church, were torn from their sanctuary in St. Sophia and sold as slaves in the markets of Syria.

Thus was lost the second city of Christendom to the infidels, and the old Roman Empire, whose restoration had been a mediaeval idea for centuries, perished for ever.

* * * * *

Retribution, at least according to human ideas of justice, often seems to lag in history; but in the case of the fall of Constantinople some of the culprits most responsible, on account of their selfish indifference, were speedily called on to pay the penalty. Mohammed II, his ambition inflated by what he had already achieved, planned the reduction of Christendom, declaring that he would feed his horse from the altar of St. Peter’s in Rome. With an enormous army he advanced through Serbia and besieged Belgrade; but here he was thrust back by a Christian champion, John Hunyadi, ‘the wicked one’, as the title reads in Turkish, with such loss of men and material ‘that Hungary and eastern Germany were saved from serious danger for eighty years’.

With the Balkan states it was otherwise, whose governments, divided in their counsels, jealous in their rivalries, had been incapable of the union that could alone have saved them, and one by one they were crushed beneath ‘the Conqueror’s’ heel. Greece also came under Moslem domination, and finally the islands of the Aegean Sea that Venice had torn from Constantinople in the interests of her trade were wrested away from her, leaving her faced with the prospect of commercial ruin.