Editor’s note: The following work by G. K. Chesterton was published in 1924. All spelling in the original.

There is an image or fancy I have sometimes called up, and thought of setting down, about an old stone cross that had its head knocked off in the barbarian wars, and it was afterwards worshipped by the barbarians as a primal and prehistoric monument of the hammer of Thor. The barbarians who worshipped it, or at least preserved it, would, of course, include many generations of progressive persons, and among others the professors of history at our modern schools and universities. For such a story would really be a very compact and correct statement of what happened in history, in contradistinction to what happens in histories. Most of the Victorian facts and fictions about the northern war between the White Christ and the old gods, erred merely in calling them the old gods, or at least in making them out much older than they probably were. Historians who hold that Odin was a man, make him a man but a little time before Christ; and I should not be surprised to learn he became a god a considerable time after Christ. The Scandinavian piracy, like the submarine piracy, was an interruption in our history; it was not something that created, but only something that nearly destroyed us. But the same interruption contrived to perpetuate itself later, in the form of a Teutonic theory of all our origins. In a truly Teutonic spirit, it made ruins and called them a new school of architecture. As in my parable, it knocked the cross nearly shapeless; and then was delighted to trace in shapelessness a truly Teutonic shape.

But there is another and real remnant which might stand for the same truth in a more elaborate allegory, if I had the learning to develop it. If our recent school of racial history had gone one step farther, we should never have heard again of the Roman Roads. They would all, by this time, be called the German Roads. That no other tribe of men but the Teutons could be capable of so much organisation, efficiency and endurance is a theme too obvious to demand detail. And to a properly constituted professor, the fact that Watling Street starts in Kent would be a luminous proof that the late lamented Horsa took a single stride to Chester. Nevertheless, I will maintain, with the modesty proper to an amateur, that the barbarians did not make the great roads, but only partly unmade them, by neglect and negative destruction; and of this there is another image or symbol in my mind, less simple than the fancy I have suggested, but suggestive of the same truth. And the truth is that the special burden which England has suffered is interruption; and that not merely in the invasions of the Dark Ages, but in the pedantries and perversions of much later ages. She has been turned out of her true course; and hitherto half disinherited of her legacy from Rome. Among the many great things that England still is, England is a great might-have-been.

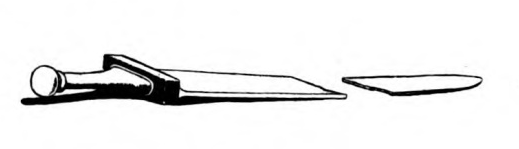

I was walking about thirty miles south of London with a friend of mine, who knows more about Roman roads than I do; which is not indeed saying much. My conviction of the Roman background of all our arts and arms is a matter of common-sense and not of scholarship. But he has a great deal of both; and he pointed out to me a certain feature in that landscape of South England, which has figured in my fancies ever since, as an emblem of all that I am trying to say. The road, or string of lanes, along which we went, started, he said, in a cathedral city by the coast and travelled straight as a bolt across the country to the point where we were walking. And from the high places by the sea, the hills, or the cathedral towers, one could almost fancy the man who planned it seeing it like a line on a chart; and that line pointed straight at London. The Roman engineers who made it must have trained and aimed it like a great gun at the gates of London, with more than the exactitude of modern science. But though it started for London, it never got there. Just in front of us the road crossed a stream by a bridge; and just beyond it the way vanished like a thing crossing the frontier of fairyland; flat across it at right angles ran a modern thoroughfare, and beyond was the wall of one of those estates that have made our modern history. That great road hung loose in the air like half of a ruined bridge; indeed, it probably depended on the little bridge behind, and had failed when it fell. The bridge would suggest that it was in the Dark Ages it was lost; though the estate beyond suggested that in the Great Pillage it was lost finally. Anyhow, the road pointed at the heart and capital of modern England straight as a Roman sword. But the Roman sword was broken.

I had come somehow to that place alone, and stood beyond the final bridge, staring south-westwards, where the long pale road faded away under the edges of a pale sunset. It was late autumn, and the wooded horizons of the Weald were already softened to the grey fringe of winter. A few dry leaves clung to the trees like crinkled copper, and a few flakes of flame-coloured cloud stained the west, like red fishes in a silver sea; but for the most part the scene was silver above and black and grey below. Nor did I note these tints and details attentively; for my mind was in a mood of meaningless and even unnatural expectation. I continued to stare down the road; and it matters nothing whether what I saw was a dream, or what is called a day-dream, or a drama none the less real because acted within the theatre of the soul. But as I stared at the distant spot where the way vanished into the woods, it was as if a dark clump detached itself from the dark trees and was moving up the road. As it came nearer it seemed too rectangular for a living thing; it was covered with plates, like a beetle; and then I saw that it was a body of armed men with square shields on their square shoulders. Half-way across the bridge it halted, and there was a voice calling out orders; but in a strange tongue. As it came nearer the shields were seen to be oblong and curved to cover the body; and some of the helmets were made towering and almost horrible with horsehair. But among the helmets was something even stranger; the eye was for a moment riveted upon a monster — a man with the head of a beast. He held the staff of a standard in a human hand; and a second glance showed the head to be a hairy mask and cap, with a human face below. Behind him was the column of bristling infantry, with a few horsemen; and one was bare headed and wrapped in a red cloak, like a crimson cloud of that stormy after-glow. For his head was dark against the light of the west, and even in my dream I did not see his face. But before him, just above the man with the hairy helmet, a stray flash of torch or reflected sun took fire upon the golden eagles.

But the strangest thing of all was that when they came to the shores of that small stream they halted again, and that in a wholly different fashion. Once more there were ringing voices giving commands; and though the accent was still strange to me, I partly recognised words that I had learnt, or refused to learn, long ago at school. I understood only the effect of the orders, which was strange enough; for the column seemed to halt and break up as if brought to a standstill, accepting the stoppage with gestures of a weary humour, like soldiers confronted with an immense military obstacle. It was as if they were sitting down before a beseiged city. Nor should I have understood any of their talk, but for one tag familiar even out of school. For a young man with a plumed helmet, getting down from his horse, laughed and said to a fellow officer, “Rusticus expectat…” [1] Something made me turn my head to the road behind me, at which he was looking as he laughed; and I saw that the bridge was gone, and I thought the river was wider. And even as I turned again towards the south, I heard the great roll of the end of the quotation, “per omne volubilis aevum.” [2]

Silence and even sleep seemed already to have fallen on that strange host; they gathered in the shadows of the woods to the left and right of the road; and the road itself again lay white and empty under the wan evening sky. And again I felt the strain on my mind of a strange vigilance. I could not take my eyes from the empty end of the road; but now it was not my eyes but my ears that had the first warning. Far away in the dim forests I thought I heard a man singing. As the voice came nearer and nearer it brought with it a new band of men, sitting on horses behind long, triangular shields. But the singer rode ahead of them and filled the woods with his voice; and the words had a nasal clang, like the groaning of great bronze and iron.

De dulce France, des humes de sun lign,

De Carlemagne sun seignor ki l’nurrit.

And I thought it was the song that he had sung only yesterday in battle by the Sussex sea, throwing up his sword and catching it as he led the lances of his lord to triumph. But though he had triumphed, he was not singing of triumph. Before the fight and after, he sang of sorrow and vain valour in the chasm of the Pyrenees, and of a few brave men betrayed and forgotten. For this was the vanguard of a victorious army advancing into the land; and its minstrel still sang of the great beauty of defeat, as is the manner of heroes.

Yet these also came to a halt upon the river bank and gazed across the river. They all looked like iron birds of prey with their beaks turned towards me; but this was, in part, because of their helmets and nose-pieces of steel that added something aquiline and rapacious to their faces.

Above, their helmets rose in high peaks like hoods of elves, but they were hoods of iron; and their coats were covered with iron rings as if they were wrapped up to the neck in chains. But despite the strange helmet, that had all the terrors of a mask of steel, their eyes seemed rather sad than otherwise, as they gazed across the broken bridge and the flowing river. And I thought I understood a little the song their leader sang in the hour of victory; and thought they looked on this new land with some sense of doubt and fate, and frustration; as Roland, dying, had thought of the fair fields of France, and his kindred, and the love of Charlemagne, his lord.

The two strange hosts had halted side by side, as in a sort of bivouac; here and there it seemed that they were lighting spectral fires; when there came up along the road behind them the noise of a new and a much mightier procession. It bore banners of all the most fantastic shapes and colours; but high above even the banners moved great wooden towers on wheels, each open like a scaffolding, and taller than the trees. The network of crossing beams was black against the sunset glow; but the eye could still see, though in shadow, the rich colours of captured standards and sacred carpets hung on them as trophies, each as sumptuous as a separate sunset. And here and there burned with an unearthly brilliance, in the swinging vessels with which these soldiers slung it in battle, the Greek fire that they had taken from the Saracens. And as the eye took in the more gorgeous hues and emblems of the triumph, the mind could dimly realise the meaning of their new and almost monstrous gaiety, and why these men in their exultation dragged through English lanes, like the towers of travelling cathedrals, those high wooden engines with which they had stormed Jerusalem.

Yet this happier army halted also, in a sort of wonder, at the ending of the way. In contrast to the grey iron and brown leather of the last cavalcade, these men had much more elaborate armour, and pictures were painted on all their shields. And in contrast to the strong and solitary voice that sang the death of Roland, this company was full of a stir and tinkle of light music from instruments of many shapes and sizes, touched by troubadours and minstrels of many tongues. Yet here, too, a voice seemed to rise above the rest at last, like a lark above birds. It was the voice of a young man, dark, and clad wholly in red, who sat on horseback with a small gold harp in his hand, and the words seemed to come out of the heart or cor cordium [3] of the ages; the air and burden of “O Richard, O mon Roi.” And though I thought he knew that, if his master was absent, it must be far away in a fortress in the Austrian forests, yet such was the strange obsession of some common thought, that he also sang with his pale and burning face turned towards London, as if it were that city that held the English king captive, and powerless to help his people.

And still the crowds coming up the road gathered and grew thicker, overflowing from the woods to the shores of the river that they could not cross. In the track of the great travelling towers came coloured crowds and companies, more than I could count or remember. But I recall that there came down the road, among the rest, a body of men coarsely clad as in ragged sacks of brown, but bearing aloft a wooden statue coloured with the same habit, but ringed with rays of gold, and having in his hands red wounds like rubies. They looked a tattered band of beggars, as perhaps they were, but as they came they sang the Canticle of the Sun. They sang of the fire, our brother, and the water, our sister, and all the quaint figures of the happiest of human songs; but as they sang the last verse, “Praise be Our Lord for the death of the body,” they came to the bank of the river, and stopped as though it were the Styx.

For the great multitude that now more and more covered the fields to the south of the river was no longer a mere army, though it was literally glorious as an army with banners. It was the army of the arts of peace, of the crafts that can create and not destroy; but it had all the gold and gay blazonry which, in later and sadder times, has fallen from the labourer and the clerk, and clung only to the solitary figure of the soldier. For I saw pass before me something which seems in modern books merely a satire or parody, the pride and pageant of labour; the glory of the guilds. The strange and shining shapes of the primary human tools took on all the terrors of heraldry, and all the symbolism now only seen here and there in the decaying sign over some shop in a little town. And so, in the same fashion, the clamour and laughter of that mighty crowd were made up of many voices, of things now fallen, but still faintly familiar ; a voice only heard to-day in a few old street- cries, which the rich put up notices to restrain. For these men spoke my own language, and the men of my own time might have been as lucky as they. There were indeed scholars among them, poor students of the sort that will riot in the streets upon a point of metaphysics. And one of these, pointing across the river, uttered another tag of familiar Latin. But it was from that Roman poet who was the magician of the Middle Ages, and it contains indeed the magic of all ages: tendentesque manus ripoe ulterioris amore.[4] But for the most part the popular noise was national and in that manner almost modern; and I began to catch, in particular, a refrain caught up here and there, and repeated, and combining at last in one half-mocking chorus; an old song now known only among children as a nursery rhyme:

London bridge is broken down,

My fair lady.

As the twilight darkened and that chorus grew louder and more derisive, I seemed to lose a little the thread of all these strange events, and could not fix so clearly in my memory the more chaotic things that began to break up the vision. It seemed that from beyond the crowd came the trampling of skirmishing horsemen, and pistol shots, and the noise of new quarrels; and the whole scene grew more and more confused hour after hour, till I saw a red glow in the grey distance, and knew that men were burning hay-ricks and agricultural machinery.

And then in a lull between two of these lurid outbreaks I heard, coming along the old road, the sound of a single horseman. Something told me that his horse knew the road, and could almost have carried his rider sleeping; for indeed they knew all that maze of south country roads; and if the ghosts that return were the ghosts that matter, that grey horse and his rider would still pass through the English hamlets at night. He rode right up to the brink of the river, and dismounted; and alone among all those visitants, he spoke to me directly.

“London Bridge is broken down,” he said. “What does the rhyme say? ‘Build it up with pins and needles’; and that’s the sort of thing the Jews and jobbers and dirty Scotch economists think it can be built up with; the fellows who talk about how many of their slaves it takes to make a pin. Well, we shan’t get to the Wen to-night.”

But for old fashions in coat and collar, he might have been a farmer of my own time; but when he said that, I knew that the strong body that stood before me lay buried miles away in a little church at Farnham.

“Whether it’s any good going to the Wen,” he said, “or trying to make it better, after what they’ve done with it since Bloody Bess, I leave to the noble noodle-headed lords and right honourable pocket-borough gentlemen; to my Lord Castlereagh, the renegade Irish liar, who talks about the wisdom of our ancestors. But my Lord Castlereagh cut his throat; and his friends say he went mad. Mark you, his friends say he went mad; it’s the whole defence, blessing and beatification they can give him, to say he went mad. I say he went sane; he saw himself for a moment; and, of course, he cut his throat. It was the one truly sane act; and I hope you’ll tell the base, stinking, swindling lords and liars that dare to talk about the foul-mouthed Cobbett, that I did his lordship handsome justice about that.”

He spoke with an extraordinary force and violence that seemed to shake the air about him; but as it seemed that the strong subject-matter almost obstructed the subject, I reminded him that he had spoken of our ancestors, and the word lifted his grumbling into a great thunder.

“These are our ancestors,” he cried in a great voice that echoed on the road. “These are the men that built your great roads, that built your great churches; the only men who ever built anything for you. The land-grabbers and usurers have only built things for themselves; like that fellow with the estate over there, who has built his own garden wall flat across the great road into England. God knows whether any Englishman will ever get into England again.”

And even as he spoke the words, as if he had uttered a spell, it seemed somehow that the very air of all that scene was subtly changed; as when a remote window has been opened, or some tune in the distance has begun or ceased. It seemed as if all were conscious that a thing wholly new had entered in silence on the theatre of the ancient road; and far away at the end of it, I saw yet another brown body of men crawling towards us. It was literally crawling, for as they came nearer, I saw that many were limping on one leg, and most upon crutches, and nearly all were crippled in some fashion; but on their brown uniforms were stars and crosses whose names were the names of far-off cities and the frontier rivers of a strange land. For these last men also, like the first, came across the seas from the creative furnace of Christendom; and had seen blaze in the black eclipse of battle, as the vision of an instant, the thing that we were meant to be. And my heart was lifted, for these at least were men of my day and generation; and as they passed along the lines, were lifted in salute together all the swords and lances of the armies of the dead; and all their fathers did them reverence.

These men alone marched straight on to the bridge as if it were still standing; and when I looked at it, I saw that it was still standing. I looked at it again and steadily; there was no doubt of its solidity, but there was no life near it but my own. And beyond was nothing but the blank wall across the end of the empty road.

______________________________

Footnotes

[1] “The peasant is awaiting.”

[2] “through an entire eternity/life of changing”

[3] heart of hearts

[4] “stretching forth their hands with a love for the further shore”