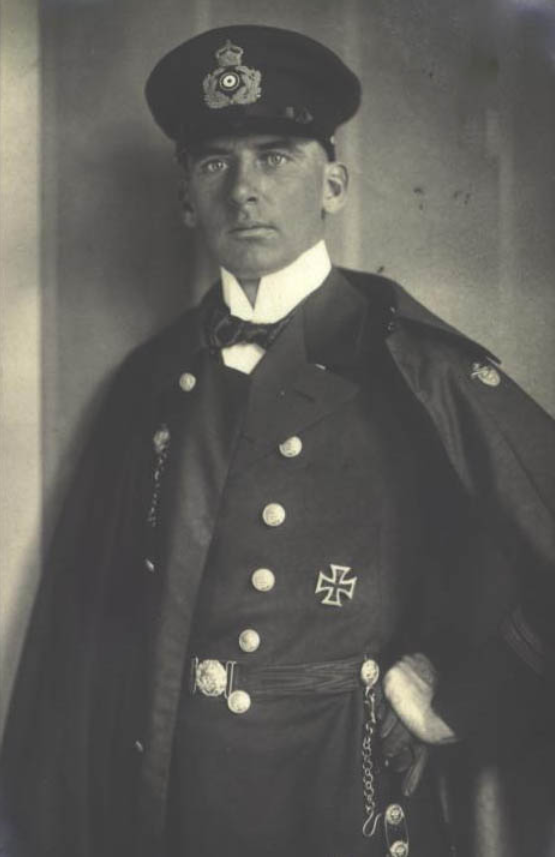

Editor’s note: The following account of the German light cruiser Emden’s famous raiding career is extracted from World’s War Events, Vol. I, edited by Allen L. Churchill (published 1919). All spelling in the original.

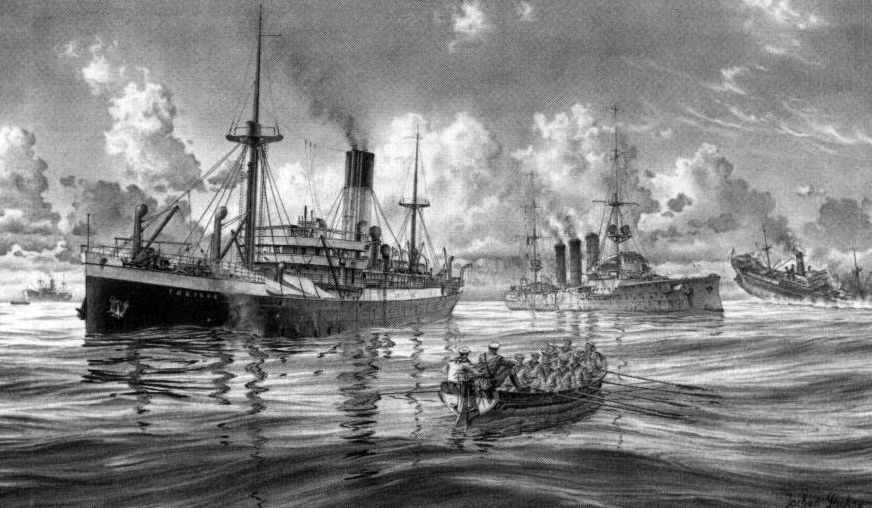

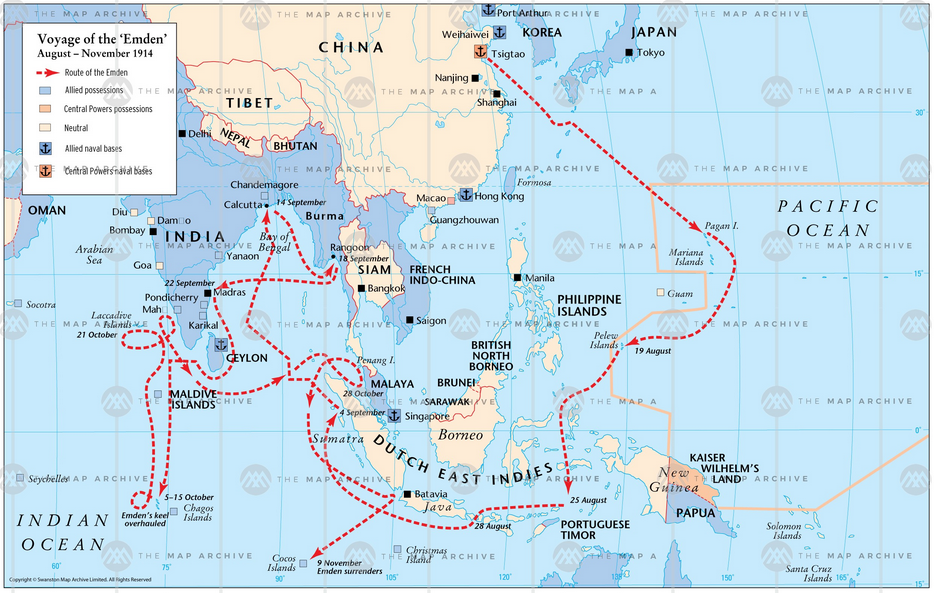

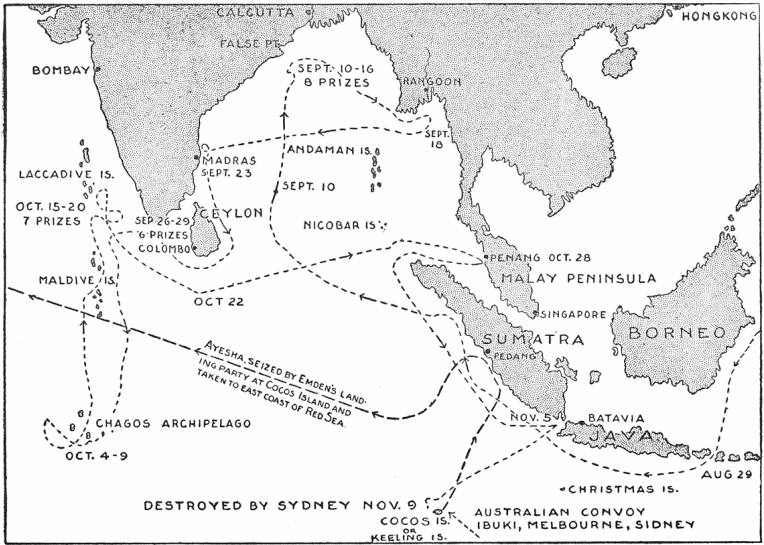

“We on the Emden had no idea where we were going, as on August 11, 1914, we separated from the cruiser squadron, escorted only by the coaler Markomannia. Under way, the Emden picked up three officers from German steamers. That was a piece of luck, for afterward we needed many officers for the capturing and sinking of steamers, or manning them when we took them with us. On September 10 the first boat came in sight. We stop her. She proves to be a Greek tramp, chartered from England. On the next day we met the Indus, bound for Bombay, all fitted up as a troop transport, but still without troops. That was the first one we sunk. The crew we took aboard the Markomannia. ‘What’s the name of your ship?’ the officers asked us. ‘Emden! Impossible. Why, the Emden was sunk long ago in battle with the Ascold!’

“Then we sank the Lovat a troop transport ship, and took the Kabinga along with us. One gets used quickly to new forms of activity. After a few days capturing ships became a habit. Of the twenty-three which we captured, most of them stopped after our first signal. When they didn’t, we fired a blank shot. Then they all stopped. Only one, the Clan Mattesen, waited for a real shot across the bow before giving up its many automobiles and locomotives to the seas. The officers were mostly very polite and let down rope ladders for us. After a few hours they’d be on board with us. We ourselves never set foot in their cabins, nor took charge of them. The officers often acted on their own initiative and signaled to us the nature of their cargo; then the Commandant decided as to whether to sink the ship or take it with us. Of the cargo, we always took everything we could use, particularly provisions. Many of the English officers and sailors made good use of the hours of transfer to drink up the supply of whisky instead of sacrificing it to the waves. I heard that one Captain was lying in tears at the enforced separation from his beloved ship, but on investigation found that he was merely dead drunk. But much worse was the open betrayal which many practiced toward their brother Captains, whom they probably regarded as rivals. ‘Haven’t you met the Kilo yet? If you keep on your course two hours longer, you must overhaul her,’ one Captain said to me of his own accord. To other tips from other Captains we owed many of our prizes. I am prepared to give their names,” Captain Mücke added.

“The Captain of one ship once called out cheerily: ‘Thank God I’ve been captured!’ He had received expense money for the trip to Australia, and was now saved half the journey!

“We had mostly quiet weather, so that communication with captured ships was easy. They were mostly dynamited, or else shot close to the water line. The sinking process took longer or shorter, according to where they were struck and the nature of the cargo. Mostly the ships keeled over on their sides till the water flowed down the smokestacks, a last puff of smoke came out, and then they were gone. Many, however, went down sharply bow first, the stern rising high in the air.

“On the Kabinga the Captain had his wife and youngster with him. He was inclined at first to be disagreeable. ‘What are you going to do with us? Shall we be set out in boats and left to our fate?’ he asked. Afterward he grew confidential, like all the Captains, called us ‘Old Chap,’ gave the Lieutenant a nice new oilskin, and as we finally let the Kabinga go wrote us a letter of thanks, and his wife asked for an Emden armband and a button. They all gave us three cheers as they steamed away. ‘Come to Calcutta some time!’ was the last thing the Captain said, ‘and catch the pilots so that those [unprintable seaman’s epithet] fellows will feel something of the war, too.’

“A few days later, by Calcutta, we made one of our richest hauls, the Diplomat, chock full of tea—we sunk $2,500,000 worth. On the same day the Trabbotch, too, which steered right straight toward us, literally into our arms.

“But now we wanted to beat it out of the Bay of Bengal, because we had learned from the papers that the Emden was being keenly searched for. By Rangoon we encountered a Norwegian tramp, which, for a cash consideration, took over all the rest of our prisoners of war. Later on another neutral ship rejected a similar request and betrayed us to the Japanese into the bargain. On September 23 we reached Madras and steered straight for the harbor. We stopped still 3,000 yards before the city. Then we shot up the oil tanks. Three or four burned up and illuminated the city. They answered. Several of the papers asserted that we left with lights out. On the contrary, we showed our lights so as to seem to indicate that we were going northward; only later did we put them out, turn around, and steer southward. As we left we could see the fire burning brightly in the night, and even by daylight, ninety sea miles away, we could still see the smoke from the burning oil tanks. Two days later we navigated around Ceylon, and could see the lights of Colombo. On the same evening we gathered in two more steamers, the King Lund and Tyweric. The latter was particularly good to us, for it brought us the very latest evening papers from Colombo, which it had only left two hours before.

“Everything went well, the only trouble was that our prize, the Markomannia, didn’t have much coal left. We said one evening in the mess: ‘The only thing lacking now is a nice steamer with 500 tons of nice Cardiff coal.’ The next evening we got her, the Burresk, brand-new, from England on her maiden voyage, bound for Hongkong. Then followed in order the Riberia, Foyle, Grand Ponrabbel, Benmore, Troiens, Exfort, Grycefale, Sankt Eckbert, Chilkana. Most of them were sunk; the coal ships were kept. The Eckbert was let go with a load of passengers and captured crews. We also sent the Markomannia away because it hadn’t any more coal. She was later captured by the English together with all the prize papers about their own captured ships. All this happened before October 20; then we sailed southward, to Deogazia, southwest of Colombo. South of Lakadiven on Deogazia some Englishmen came on board, solitary farmers who were in touch with the world only every three months through schooners. They knew nothing about the war, took us for an English man-of-war, and asked us to repair their motor boat for them. We kept still and invited them to dinner in our officers’ mess. Presently they stood still in front of the portrait of the Kaiser, quite astounded. ‘This is a German ship!’ We continued to keep still. ‘Why is your ship so dirty?’ they asked. We shrugged our shoulders. ‘Will you take some letters for us?’ they asked. ‘Sorry, impossible; we don’t know what port we’ll run into.’ Then they left our ship, but about the war we told them not a single word.

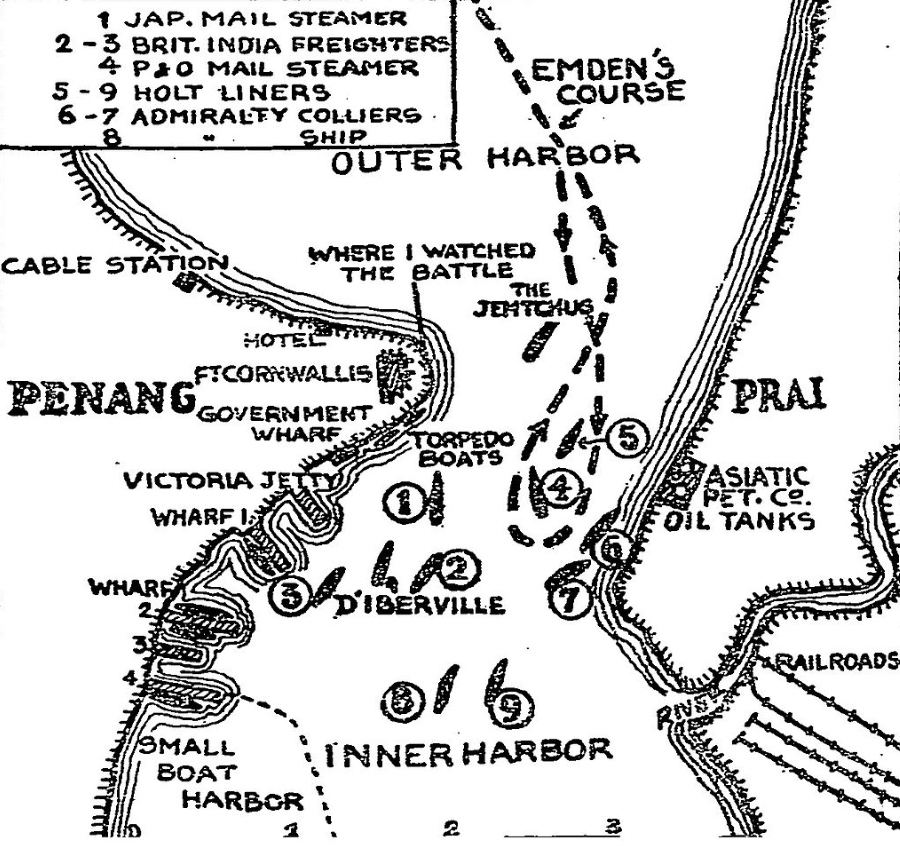

“Now we went toward Miniko, where we sank two ships more. The Captain of one of them said to us: ‘Why don’t you try your luck around north of Miniko? There’s lots of ships there now?’ On the next day we found three steamers to the north, one of them with much desired Cardiff coal. From English papers on captured ships we learned that we were being hotly pursued. The stokers also told us a lot. Our pursuers evidently must also have a convenient base. Penang was the tip given us. There we had hopes of finding two French cruisers.

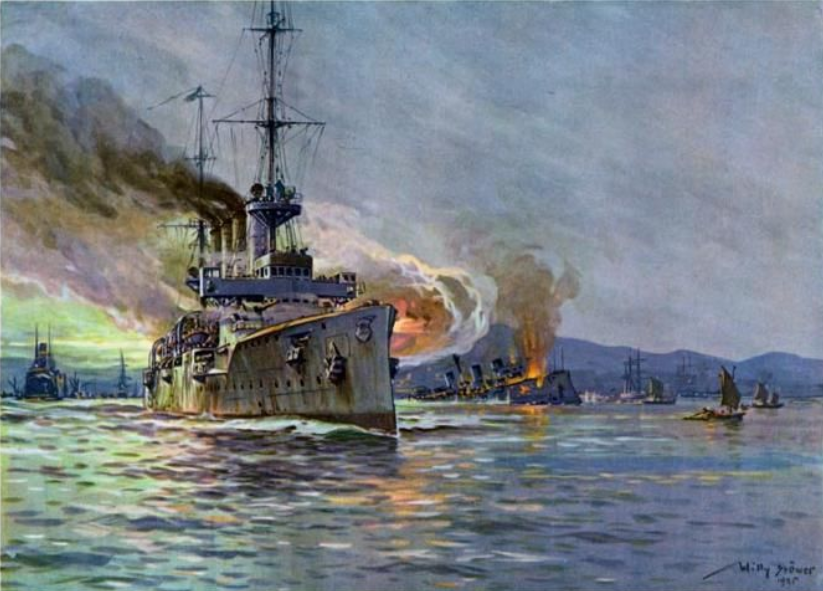

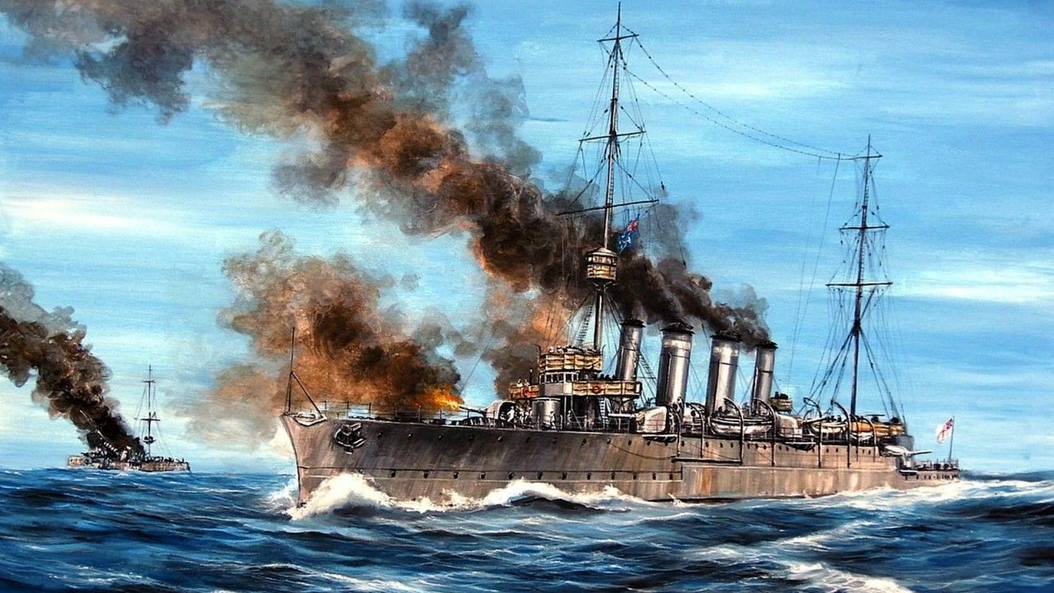

“One night we started for Penang. On October 28 we raised our very practicable fourth smokestack—Mücke’s own invention. As a result, we were taken for English or French. The harbor of Penang lies in a channel difficult of access. There was nothing doing by night; we had to do it at daybreak. At high speed, without smoke, with lights out, we steered into the mouth of the channel. A torpedo boat on guard slept well. We steamed past its small light. Inside lay a dark silhouette; that must be a warship! But it wasn’t the French cruiser we were looking for. We recognized the silhouette—dead sure; that was the Russian cruiser Jemtchug. There it lay, there it slept like a rat. No watch to be seen. They made it easy for us. Because of the narrowness of the harbor we had to keep close; we fired the first torpedo at 400 yards. Then to be sure things livened up a bit on the sleeping warship. At the same time we took the crew quarters under fire, five shells at a time. There was a flash of flame on board, then a kind of burning aureole. After the fourth shell, the flame burned high. The first torpedo had struck the ship too deep because we were too close to it, a second torpedo which we fired off from the other side didn’t make the same mistake. After twenty seconds there was absolutely not a trace of the ship to be seen. The enemy had fired off only about six shots.

“But now another ship, which we couldn’t see, was firing. That was the French D’Ibreville, toward which we now turned at once. A few minutes later an incoming torpedo destroyer was reported. He mustn’t find us in that narrow harbor, otherwise we were finished! But it proved to be a false alarm; only a small merchant steamer that looked like a destroyer, and which at once showed the merchant flag and steered for shore. Shortly afterward a second one was reported. This time it proved to be the French torpedo boat Mousquet. It comes straight toward us. That’s always remained a mystery to me, for it must have heard the shooting. An officer whom we fished up afterward explained to me that they had only recognized we were a German warship when they were quite close to us. The Frenchman behaved well, accepted battle and fought on, but was polished off by us with three broadsides. The whole fight with both ships lasted half an hour. The commander of the torpedo boat lost both legs by the first broadside. When he saw that part of his crew were leaping overboard, he cried out: ‘Tie me fast; I will not survive after seeing Frenchmen desert their ship!’ As a matter of fact, he went down with his ship as a brave Captain, lashed fast to the mast. Then we fished up thirty heavily wounded; three died at once. We sewed a Tri-color (the French flag), wound them in it and buried them at sea, with seamen’s honors, three salvos. That was my only sea fight. The second one I did not take part in.”

Mücke, who had been recounting his lively narrative, partly like an officer, partly like an artist, and not trying to eliminate the flavor of adventure, now takes on quite another tone as he comes to tell of the end of the Emden:

“On November 9 I left the Emden in order to destroy the wireless plant on the Cocos Island. I had fifty men, four machine guns, about thirty rifles. Just as we were about to destroy the apparatus it reported: ‘Careful; Emden near.’ The work of destruction went smoothly. The wireless operator said: ‘Thank God! it’s been like being under arrest day and night lately.’ Presently the Emden signaled to us: ‘Hurry up.’ I pack up, but simultaneously wails the Emden’s siren. I hurry up to the bridge, see the flag ‘Anna’ go up. That means ‘Weigh anchor.’ We ran like mad into our boat, but already the Emden’s pennant goes up, the battle flag is raised, they fire from starboard.

“The enemy is concealed by the island and therefore not to be seen, but I see the shells strike the water. To follow and catch the Emden is out of the question; she’s going twenty knots, I only four with my steam pinnace. Therefore, I turn back to land, raise the flag, declare German laws of war in force, seize all arms, set up my machine guns on shore in order to guard against a hostile landing. Then I run again in order to observe the fight. From the splash of the shells it looked as if the enemy had fifteen-centimeter guns, bigger, therefore, than the Emden’s. He fired rapidly, but poorly. It was the Australian cruiser Sydney.”

“Have you heard?” Mücke suddenly asked in between, “if anything has happened to the Sydney? At the Dardanelles maybe?” And his hatred of the Emden’s “hangman” is visible for a second in his blue eyes. Then he continues:

“According to the accounts of the Englishmen who saw the first part of the engagement from shore, the Emden was cut off rapidly. Her forward smokestack lay across the ship. She went over to circular fighting and to torpedo firing, but already burned fiercely aft. Behind the mainmast several shells struck home; we saw the high flame. Whether circular fighting or a running fight now followed, I don’t know, because I again had to look to my land defenses. Later I looked on from the roof of a house. Now the Emden again stood out to sea about 4,000 to 5,000 yards, still burning. As she again turned toward the enemy, the forward mast was shot away. On the enemy no outward damage was apparent, but columns of smoke showed where shots had struck home. Then the Emden took a northerly course, likewise the enemy, and I had to stand there helpless gritting my teeth and thinking: ‘Damn it; the Emden is burning and you aren’t on board!’ An Englishman who had also climbed up to the roof of the house, approached me, greeted me politely, and asked: ‘Captain, would you like to have a game of tennis with us?’

“The ships, still fighting, disappeared beyond the horizon. I thought that an unlucky outcome for the Emden was possible, also a landing by the enemy on Keeling Island, at least for the purpose of landing the wounded and taking on provisions. As, according to the statements of the Englishmen, there were other ships in the neighborhood, I saw myself faced with the certainty of having soon to surrender because of a lack of ammunition. But for no price did I and my men want to get into English imprisonment. As I was thinking about all this, the masts again appear on the horizon, the Emden steaming easterly, but very much slower. All at once the enemy, at high speed, shoots by, apparently, quite close to the Emden. A high, white waterspout showed among the black smoke of the enemy. That was a torpedo. I see how the two opponents withdrew, the distance growing greater between them; how they separate, till they disappear in the darkness. The fight had lasted ten hours.

“I had made up my mind to leave the island as quick as possible. The Emden was gone; the danger for us growing. In the harbor I had noticed a three-master, the schooner Ayesha. Mr. Ross, the owner of the ship and of the island, had warned me that the boat was leaky, but I found it quite a seaworthy tub. Now quickly provisions were taken on board for eight weeks, water for four. The Englishmen very kindly showed us the best water and gave us clothing and utensils. They declared this was their thanks for our ‘moderation’ and ‘generosity.’ Then they collected the autographs of our men, photographed them, and gave three cheers as our last boat put off. It was evening, nearly dark. We sailed away. After a short address, amid three hurrahs, I raised the German war flag on ‘S.M.S. Ayesha.'”

“The Ayesha proved to be a really splendid ship,” Mücke continued, and whenever he happens to speak of this sailing ship he grows warmer. One notices the passion for sailing which this seaman has, for he was trained on a sailing ship and had won many prizes in the regattas at Kiel. “But we had hardly any instruments,” he narrated, “we had only one sextant and two chronometers on board, but a chronometer journal was lacking. Luckily I found an old ‘Indian Ocean Directory’ of 1882 on board; its information went back to the year 1780.

“At first we had to overhaul all the tackle, for I didn’t trust to peace, and we had left the English Captain back on the island. I had said: ‘We are going to East Africa.’ Therefore I sailed at first westward, then northward. There followed the monsoons, but then also long periods of dead calm. Then we scolded! Only two neutral ports came seriously under consideration: Batavia and Padang. At Keeling I cautiously asked about Tsing-tao, of which I had naturally thought first, and so quite by chance learned that it had fallen. Now I decided for Padang, because I knew I would be more apt to meet the Emden there, also because there was a German Consul there, because my schooner was unknown there, and because I hoped to find German ships there and learn some news. ‘It’ll take you six to eight days to reach Batavia,’ a Captain had told me at Keeling. Now we needed eighteen days to reach Padang, the weather was so rottenly still.

“We had an excellent cook on board; he had deserted from the French Foreign Legion. But with water we had to go sparingly, each man received three glasses daily. When it rained, all possible receptacles were placed on deck and the main sail was spread over the cabin roof to catch the rain. The whole crew went about naked, in order to spare our wash, for the clothing from Keeling was soon in rags. Toothbrushes were long ago out of sight. One razor made the rounds of the crew. The entire ship had one precious comb.

“As at length we came in the neighborhood of Padang, on November 26, a ship appeared for the first time and looked after our name. But the name had been painted over, because it was the former English name. As I think, ‘You’re rid of the fellow,’ the ship comes again in the evening, comes within a hundred yards of us. I send all men below deck. I promenade the deck as the solitary skipper. Through Morse signals the stranger betrayed its identity. It was the Hollandish torpedo boat Lyn. I asked by signals, first in English, then twice in German: ‘Why do you follow me?’ No answer. The next morning I find myself in Hollandish waters, so I raise pennant and war flag. Now the Lyn came at top speed past us. As it passes, I have my men line up on deck, and give a greeting. The greeting is answered. Then, before the harbor at Padang, I went aboard the Lyn in my well and carefully preserved uniform and declared my intentions. The commandant opined that I could run into the harbor, but whether I might come out again was doubtful.”

“On the South Coast,” interjected Lieutenant Wellman, who at that time lay with a German ship before Padang and only later joined the landing corps of the Emden, “we suddenly saw a three-master arrive. Great excitement aboard our German ship, for the schooner carried the German war flag. We thought she came from New Guinea and at once made all boats clear, on the Kleist, Rheinland, and Choising, for we were all on the search for the Emden. When we heard that the schooner carried the landing corps, not a man of us would believe it.”

“They wanted to treat me as a prize!” Mücke now continued. “I said, ‘I am a man of war,’ and pointed to my four machine guns. The harbor authorities demanded a certification for pennant and war flag, also papers to prove that I was the commander of this warship. I answered, for that I was only responsible to my superior officers. Now they advised me the most insistently to allow ourselves to be interned peacefully. They said it wasn’t at all pleasant in the neighborhood. We’d fall into the hands of the Japanese or the English. As a matter of fact, we had again had great luck. On the day before a Japanese warship had cruised around here. Naturally, I rejected all the well-meant and kindly advice, and did this in presence of my lieutenants. I demanded provisions, water, sails, tackle, and clothing. They replied we could take on board everything which we formerly had on board, but nothing which would mean an increase in our naval strength. First thing, I wanted to improve our wardrobe, for I had only one sock, a pair of shoes, and one clean shirt, which had become rather seedy. My comrades had even less. But the Master of the Port declined to let us have not only charts, but also clothing and toothbrushes, on the ground that these would be an increase of armament. Nobody could come aboard, nobody could leave the ship without permission. I requested that the Consul be allowed to come aboard. This Consul, Herr Schild, as also the Brothers Bäumer, gave us assistance in the friendliest fashion. From the German steamers boats could come alongside and talk with us. Finally we were allowed to have German papers. They were, to be sure, from August. Until March we saw no more papers.

“Hardly had we been towed out again after twenty-four hours, on the evening of the 28th, when a searchlight appeared before us. I think: ‘Better interned than prisoner.’ I put out all lights and withdrew to the shelter of the island. But they were Hollanders and didn’t do anything to us. Then for two weeks more we drifted around, lying still for days. The weather was alternately still, rainy and blowy. At length a ship comes in sight—a freighter. It sees us and makes a big curve around us. I make everything hastily ‘clear for battle.’ Then one of our officers recognizes her for the Choising. She shows the German flag. I send up light rockets, although it was broad day, and go with all sails set that were still setable, toward her. The Choising is a coaster, from Hongkong for Siam. It was at Singapore when the war broke out, then went to Batavia, was chartered loaded with coal for the Emden, and had put into Padang in need, because the coal in the hold had caught fire. There we had met her.

“Great was our joy now. I had all my men come on deck and line up for review. The fellows hadn’t a rag on. Thus, in Nature’s garb, we gave three cheers for the German flag on the Choising. The men on the Choising told us afterward ‘we couldn’t make out what that meant, those stark naked fellows all cheering!’ The sea was too high, and we had to wait two days before we could board the Choising on December 16. We took very little with us; the schooner was taken in tow. In the afternoon we sunk the Ayesha and we were all very sad. The good old Ayesha had served us faithfully for six weeks. The log showed that we had made 1,709 sea miles under sail since leaving Keeling. She wasn’t at all rotten and unseaworthy, as they had told me, but nice and white and dry inside. I had grown fond of the ship, on which I could practice my old sailing manoeuvres. The only trouble was that the sails would go to pieces every now and then because they were so old.

“But anyway she went down quite properly, didn’t she?” Mücke turned to the officer. “We had bored a hole in her; she filled slowly and then all of a sudden plump disappeared! That was the saddest day of the whole month. We gave her three cheers, and my next yacht at Kiel will be named Ayesha, that’s sure.

“To the Captain of the Choising I had said, when I hailed him: ‘I do not know what will happen to the ship. The war situation may make it necessary for me to strand it.’ He did not want to undertake the responsibility. I proposed that we work together, and I would take the responsibility. Then we traveled together for three weeks, from Padang to Hodeida. The Choising was some ninety meters long and had a speed of nine miles, though sometimes only four. If she had not accidentally arrived I had intended to cruise high along the west coast of Sumatra to the region of the northern monsoon. I came about six degrees north, then over Aden to the Arabian coast. In the Red Sea the northeastern monsoon, which here blows southeast, could bring us to Djidda. I had heard in Padang that Turkey is allied with us, so we would be able to get safely through Arabia to Germany.

“I next waited for information through ships, but the Choising did not know anything definite, either. By way of the Luchs, the Königsberg, and Kormoran the reports were uncertain. Besides, according to newspapers at Aden, the Arabs were said to have fought with the English. Therein there seemed to be offered an opportunity near at hand to damage the enemy. I therefore sailed with the Choising in the direction of Aden. Lieutenant Gerdts of the Choising had heard that the Arabian railway now already went almost to Hodeida, near the Perim Strait. The ship’s surgeon there, Docounlang, found confirmation of this in Meyer’s traveling handbook. This railway could not have been taken over by the Englishmen, who always dreamed of it. By doing this they would have further and completely wrought up the Mohammedans by making more difficult the journey to Mecca. Best of all, we thought, we’ll simply step into the express train and whizz nicely away to the North Sea. Certainly there would be safe journeying homeward through Arabia. To be sure, we hadn’t maps of the Red Sea; but it was the shortest way to the foe, whether in Aden or in Germany.

“Therefore, courage! Adenwards!”

“On the 7th of January, between 9 and 10 o’clock in the evening, we sneaked through the Strait of Perim. That lay swarming full of Englishmen. We steered along the African coast, close past an English cable layer. That is my prettiest delight—how the Englishmen will be vexed when they learn that we have passed smoothly by Perim. On the next evening we saw on the coast a few lights upon the water. We thought that must be the pier of Hodeida. But when we measured the distance by night, 3,000 meters, I began to think that must be something else. At dawn I made out two masts and four smokestacks; that was an enemy ship, and, what is more, an armored French cruiser. I therefore ordered the Choising to put to sea, and to return at night.

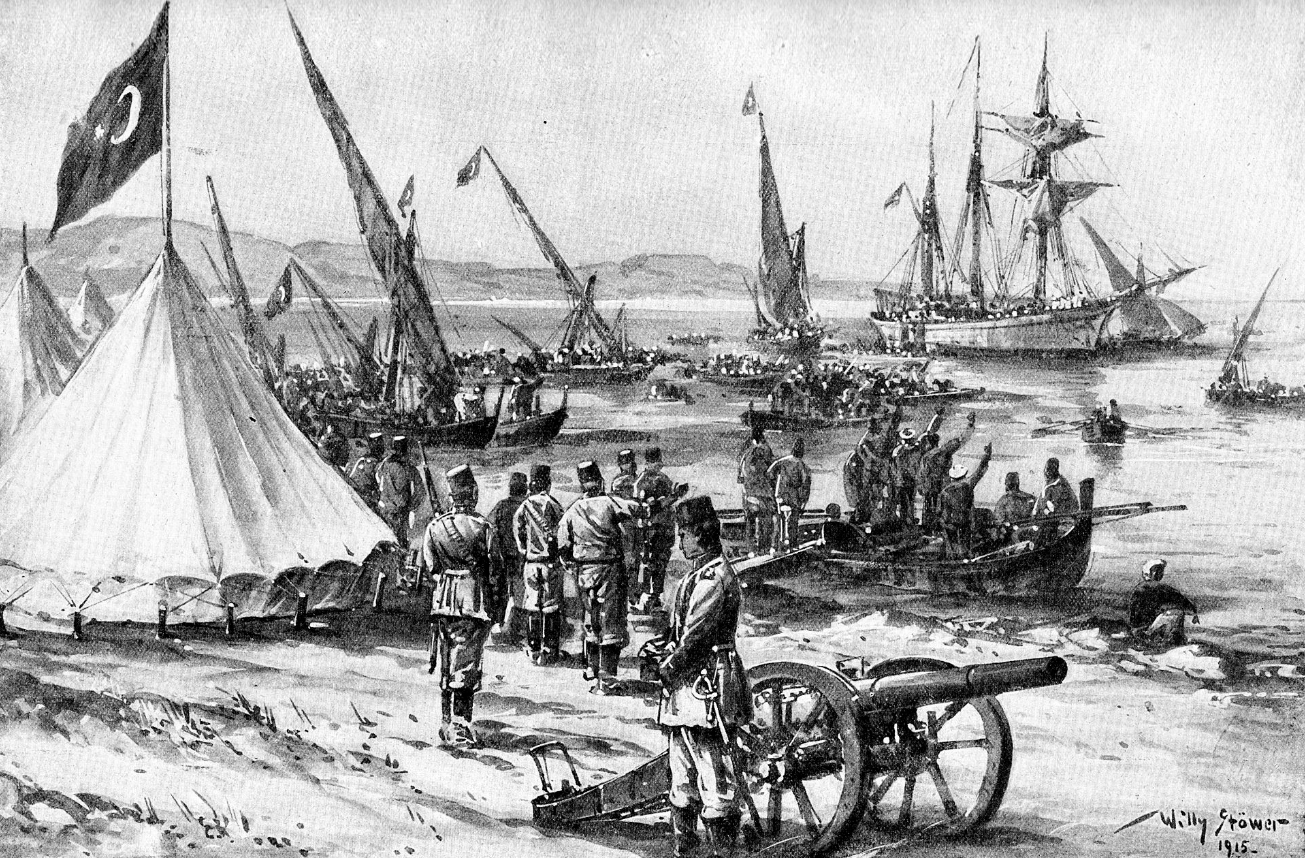

“The next day and night the same; then we put out four boats—these we pulled to shore at sunrise under the eyes of the unsuspecting Frenchmen. The sea reeds were thick. A few Arabs came close to us; then there ensued a difficult negotiation with the Arabian Coast Guards. For we did not even know whether Hodeida was in English or French hands. We waved to them, laid aside our arms, and made signs to them. The Arabs, gathering together, begin to rub two fingers together; that means ‘We are friends.’ We thought that meant ‘We are going to rub against you and are hostile.’ I therefore said: ‘Boom-boom!’ and pointed to the warship. At all events, I set up my machine guns and made preparations for a skirmish. But, thank God! one of the Arabs understood the word ‘Germans’; that was good.

“Soon a hundred Arabs came and helped us, and as we marched into Hodeida the Turkish soldiers, who had been called out against us, saluted us as allies and friends. To be sure, there was not a trace of a railway, but we were received very well, and they assured us we could get through by land. Therefore, I gave red-star signals at night, telling the Choising to sail away, since the enemy was near by. Inquiries and determination concerning a safe journey by land proceeded. I also heard that in the interior, about six days’ journey away, there was healthy highland where our fever invalids could recuperate. I therefore determined to journey next to Sana. On the Kaiser’s birthday we held a great parade in common with the Turkish troops—all this under the noses of the Frenchmen. On the same day we marched away from Hodeida to the highland.

“Two months after our arrival at Hodeida we again put to sea. The time spent in the highlands of Sana passed in lengthy inquiries and discussions that finally resulted in our foregoing the journey by land through Arabia, for religious reasons. But the time was not altogether lost. The men who were sick with malaria had, for the most part, recuperated in the highland air.

“The Turkish Government placed at our disposal two ‘sambuks’ (sailing ships) of about twenty-five tons, fifteen meters long and four meters wide. But in fear of English spies, we sailed from Jebaua, ten miles north of Hodeida. That was on March 14. At first we sailed at a considerable distance apart, so that we would not both go to pot if an English gunboat caught us. Therefore, we always had to sail in coastal water. That is full of coral reefs, however.”

“The Commander,” Lieutenant Gerdts said, “had charge of the first sambuk; I of the second, which was the larger of the two, for we had four sick men aboard. At first everything went nicely for three days. For the most part I could see the sails of the first ship ahead of me. On the third day I received orders to draw nearer and to remain in the vicinity of the first boat, because its pilot was sailing less skillfully than mine. Suddenly, in the twilight, I felt a shock, then another, and still another. The water poured in rapidly. I had run upon the reef of a small island, where the smaller sambuk was able barely to pass because it had a foot less draught than mine. Soon my ship was quite full, listed over, and all of us—twenty-eight men—had to sit on the uptilted edge of the boat. The little island lies at Jesirat Marka, 200 miles north of Jebaua. To be sure, an Arab boat lay near by, but they did not know us. Nobody could help us. If the Commander had not changed the order a few hours before and asked us to sail up closer, we would probably have drowned on this coral reef—certainly would have died of thirst. Moreover, the waters thereabouts are full of sharks, and the evening was so squally that our stranded boat was raised and banged with every wave. We could scarcely move, and the other boat was nowhere in sight. And now it grew dark. At this stage I began to build a raft of spars and old pieces of wood, that might at all events keep us afloat.

“But soon the first boat came into sight again. The commander turned about and sent over his little canoe; in this and in our own canoe, in which two men could sit at each trip, we first transferred the sick. Now the Arabs began to help us. But just then the tropical helmet of our doctor suddenly appeared above the water in which he was standing up to his ears. Thereupon the Arabs withdrew; we were Christians, and they did not know that we were friends. Now the other sambuk was so near that we could have swam to it in half an hour, but the seas were too high. At each trip a good swimmer trailed along, hanging to the painter of the canoe. When it became altogether dark we could not see the boat any more, for over there they were prevented by the wind from keeping any light burning. My men asked ‘In what direction shall we swim?’ I answered: ‘Swim in the direction of this or that star; that must be about the direction of the boat.’ Finally a torch flared up over there—one of the torches that were still left from the Emden. But we had suffered considerably through submersion. One sailor cried out: ‘Oh, pshaw! it’s all up with us now; that’s a searchlight.’ The man who held out best was Lieutenant Schmidt, who later lost his life. About 10 o’clock we were all safe aboard, but one of our typhus patients, Seaman Keil, wore himself out completely by the exertion; he died a week later. On the next morning we went over again to the wreck in order to seek the weapons that had fallen into the water. You see, the Arabs dive so well; they fetched up a considerable lot—both machine guns, all but ten of the rifles, though these were, to be sure, all full of water. Later they frequently failed to go off when they were used in firing.

“Now we numbered, together with the Arabs, seventy men on the little boat, until evening. Then we anchored before Konfida, and met Sami Bey, who is still with us. He had shown himself useful even before in the service of the Turkish Government, and has done good service as guide in the last two months. He is an active man, thoroughly familiar with the country. He procured for us a larger boat, of fifty-four tons, and he himself, with his wife, sailed alongside on the little sambuk. We sailed from the 20th to the 24th unmolested to Lith. There Sami Bey announced that three English ships were cruising about in order to intercept us. I therefore advised traveling a bit overland. I disliked leaving the sea a second time, but it had to be done.”

“Lith is, to be sure, nothing but this,” said Mücke, with a sweeping gesture toward the desert through which we were traveling, “and therefore it was very difficult to get up a caravan at once. We remained aboard ship so long. We marched away on the 28th. We had only a vague suspicion that the English might have agents here also. We could travel only at night, and when we slept or camped around a spring, there was only a tent for the sick men. Two days’ march from Jeddah, the Turkish Government, as soon as it had received news about us, sent us sixteen good camels.

“Suddenly, on the night of April 1, things became uneasy. I was riding at the head of the column. All our shooting implements were cleared for action, because there was danger of an attack by Bedouins, whom the English here had bribed. When it began to grow a bit light, I already thought: ‘We’re through for to-day’; for we were tired—had been riding eighteen hours. Suddenly I saw a line flash up before me, and shots whizzed over our heads. Down from the camels! Form a fighting line! You know how quickly it becomes daylight here. The whole space around the desert hillock was occupied. Now, up with your bayonets! Rush ’em! They fled, but returned again, this time from all sides. Several of the gendarmes that had been given us as an escort are wounded; the machine gun operator, Rademacher, falls, killed by a shot through his heart; another is wounded; Lieutenant Schmidt, in the rear guard, is mortally wounded—he has received a bullet in his chest and abdomen.

“Suddenly they waved white cloths. The Sheik, to whom a part of our camels belonged, went over to them to negotiate, then Sami Bey and his wife. In the interim we quickly built a sort of wagon barricade, a circular camp of camel saddles, rice and coffee sacks, all of which we filled with sand. We had no shovels, and had to dig with our bayonets, plates, and hands. The whole barricade had a diameter of about fifty meters. Behind it we dug trenches, which we deepened even during the skirmish. The camels inside had to lie down, and thus served very well as cover for the rear of the trenches. Then an inner wall was constructed, behind which we carried the sick men. In the very centre we buried two jars of water, to guard us against thirst. In addition we had ten petroleum cans full of water; all told, a supply for four days. Late in the evening Sami’s wife came back from the futile negotiations, alone. She had unveiled for the first and only time on this day of the skirmish, had distributed cartridges, and had conducted herself faultlessly.

“Soon we were able to ascertain the number of the enemy. There were about 300 men; we numbered fifty, with twenty-nine guns. In the night, Lieutenant Schmidt died. We had to dig his grave with our hands and with our bayonets, and to eliminate every trace above it, in order to protect the body. Rademacher had been buried immediately after the skirmish, both of them silently, with all honors.

“The wounded had a hard time of it. We had lost our medicine chest in the wreck; we had only little packages of bandages for skirmishes; but no probing instrument, no scissors were at hand. On the next day our men came up with thick tongues, feverish, and crying ‘Water! water!’ But each one received only a little cupful three times a day. If our water supply was exhausted, we would have to sally from our camp and fight our way through. Then we should have gone to pot under superior numbers. The Arab gendarmes simply cut the throats of those camels that had been wounded by shots, and then drank the yellow water that was contained in the stomachs. Those fellows can stand anything. At night we always dragged out the dead camels that had served as cover, and had been shot. The hyenas came, hunting for dead camels. I shot one of these, taking it for an enemy in the darkness.

“That continued about three days. On the third day there were new negotiations. Now the Bedouins demanded arms no longer, but only money. This time the negotiations took place across the camp wall. When I declined, the Bedouin said: ‘Beaucoup de combat,’ (lots of fight.) I replied:

“‘Please go to it!’

“We had only a little ammunition left, and very little water. Now it really looked as if we would soon be dispatched. The mood of the men was pretty dismal. Suddenly, at about 10 o’clock in the morning, there bobbed up in the north two riders on camels, waving white cloths. Soon afterward there appeared, coming from the same direction, far back, a long row of camel troops, about a hundred; they draw rapidly near by, ride singing toward us, in a picturesque train. They were the messengers and troops of the Emir of Mecca.

“Sami Bey’s wife, it developed, had, in the course of the first negotiations, dispatched an Arab boy to Jeddah. From that place the Governor had telegraphed to the Emir. The latter at once sent camel troops, with his two sons and his personal surgeon; the elder, Abdullah, conducted the negotiations; the surgeon acted as interpreter, in French. Now things proceeded in one-two-three order, and the whole Bedouin band speedily disappeared. From what I learned later, I know definitely that they had been corrupted with bribes by the English. They knew when and where we would pass and they had made all preparations. Now our first act was a rush for water; then we cleared up our camp, but had to harness our camels ourselves, for the camel drivers had fled at the very beginning of the skirmish. More than thirty camels were dead. The saddles did not fit, and my men know how to rig up schooners, but not camels. Much baggage remained lying in the sand for lack of pack animals.

“Then, under the safe protection of Turkish troops, we got to Jeddah. There the authorities and the populace received us very well. From there we proceeded in nineteen days, without mischance, by sailing boat to Elwesh, and under abundant guard with Suleiman Pasha in a five-day caravan journey toward this place, to El Ula, and now we are seated at last in the train and are riding toward Germany—into the war at last!”

“Was not the war you had enough?” I asked.

“Not a bit of it,” replied the youngest Lieutenant; “the Emden simply captured ships each time; only a single time, at Penang, was it engaged in battle, and I wasn’t present on that occasion. War? No, that is just to begin for us now.”

“My task since November,” said Mücke, “has been to bring my men as quickly as possible to Germany against the enemy. Now, at last, I can do so.”

“And what do you desire for yourself?” I asked.

“For myself,” he laughed, and the blue eyes sparkled, “a command in the North Sea.”