Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Our Soldiers, by W. H. G. Kingston (published 1863). All spelling in the original.

Final Bombardment

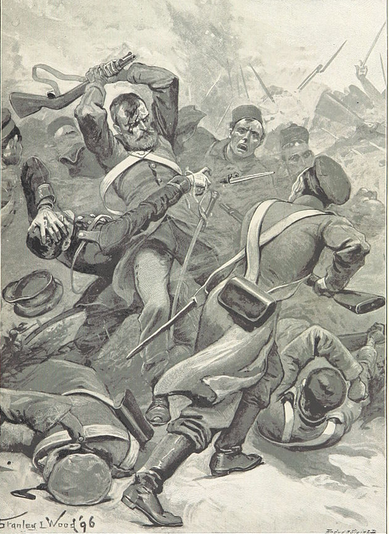

The allies had now been nearly a year before Sebastopol. The batteries opened on the 5th of September, and continued firing till noon of the 8th, when the French signal was given for the advance. Onward they rushed, and the Malakoff was taken by surprise without loss, its defenders being at dinner. The tri-colour flying from the parapet was the signal for the British to advance. A column of the light division led, and that of the second followed. The men stormed the parapet, and penetrated into the salient angle. Here Major Welsford, 97th, who led the storming party, was killed, and Colonel Handcock was mortally wounded. A most sanguinary contest ensued, but it was found impossible to maintain the position. Colonel Windham hurried back, and brought up the right wing of the 23rd, when a most brilliant charge was made, but it was of no avail: 29 officers killed and 125 wounded, with 356 non-commissioned officers and men killed, 1762 wounded, showed the severe nature of the contest. Many gallant deeds were done, but the following men deserve especial notice, for bringing in wounded men from the advanced posts during daylight on the 8th:—Privates Thomas Johnson, Bedford, Chapman, and William Freeman, of the 62nd. A considerable number performed the same merciful but dangerous work during the night. It was intended to renew the attack on the following morning with the Highland brigade under Sir Colin Campbell; but explosions were heard during the night, and when a small party advanced, the Redan was found deserted, and it was discovered that, by means of admirable arrangements, the whole Russian army were retiring by a bridge of boats to the north side, while they in the meantime had sunk all the ships of war in the harbour.

Thus was Sebastopol won undoubtedly by the gallantry of the French, for the possession of the Malakoff at that time ensured the capture of the town; but Britons may well feel proud of the heroism displayed by their countrymen from first to last of that memorable siege, and it is an example of the stuff with which English redcoats are filled: officers were killed and fully 5000 men, while upwards of 15,000 died of disease.

In October, Kinburn was taken by General Spencer; and the supplies of the Russians being cut off, they were compelled to sue for peace.

While this most bloody war showed England’s might, the undaunted bravery of her soldiers, and their admirable discipline and perseverance, it also showed wherein her weakness lay—that her commissariat was imperfect, and that much of her machinery had grown rusty from want of use. She has profited by the terrible lessons she has received; and though there is still room for improvement, the British soldier need no longer fear that sad state of things from which so many of his gallant comrades suffered in the Crimea.

Gallant deeds of the Crimean War

Here I must pause to tell of some few of the many gallant deeds done during that long and terrible year of warfare. First, how at; the bloody fight of Inkerman, Captain T. Miller, R.A., defended his guns with a handful of gunners, though surrounded by Russians, and with his own hand killed six of the foe who were attempting to capture them. How Sergeant—Major Andrew Henry, R.A., also nobly defended his guns against overwhelming numbers of the enemy, and continued to do so till he fell with twelve bayonet wounds in his body. How at the desperate charge of the Guards to retake the Sandbag battery, Lieutenant-colonel the Honourable H.M. Percy, Grenadier Guards, in face of a hot fire, charged singly into the battery, followed by his men; and how afterwards, when he found himself, with men of various regiments who had charged too far, nearly surrounded by Russians, and without ammunition, from his knowledge of the ground he was enabled, though he was wounded, to extricate them and to take them, under a heavy fire, to a spot where they obtained a supply of ammunition, and could return to the combat; and how he engaged in single combat, and wounded a Russian soldier. How Sergeant Norman and Privates Palmer and Baily were the first to volunteer to follow Sir Charles Russell to attempt retaking the Sandbag battery. Onward dashed those gallant men; the Russians could not withstand the desperate onslaught, and fled before them.

I have described those two cavalry charges at Balaclava. Several noble acts of heroism resulted from them. First, I must tell how, when Lieutenant-Colonel Morris, 17th Lancers, lay desperately wounded on the ground, in an exposed situation, after the retreat of the Light Cavalry, Surgeon Mouat, 6th Dragoons, voluntarily galloped to his rescue, and, under a heavy fire from the enemy, dressed his wounds; and how Sergeant-Major Wooden, 17th, also came to the rescue of his fallen colonel, and with Mr Mouat bore him safely from the field. How, likewise, when Captain Webb, 17th Lancers, lay desperately and mortally wounded, Sergeant-major Berryman, 17th Lancers, found him, and refused to leave him, though urged to do so. How Quarter-master-sergeant Farrell and Sergeant Malone, 13th Light Dragoons, coming by, assisted to carry him out of the fire.

Worthy of note is the conduct of Private Parkes, 4th Light Dragoons. In that fearful charge Trumpet—Major Crawford’s horse falling, he was dismounted, and lost his sword. Thus helpless, he was attacked by two Cossacks, when Parkes, whose horse was also killed, threw himself before his comrade, and drove off the enemy. Soon afterwards they were attacked by six Russians, whom Parkes kept at bay; and he retired slowly, fighting and defending Crawford, till his own sword was broken by a shot.

Sergeant Ramage, 2nd Dragoons, perceiving Private McPherson surrounded by seven Russians, galloped to his comrade’s assistance, and saved his life by dispersing the enemy. On the same day, when the heavy brigade was rallying, and the enemy retiring, finding that his horse would not leave the ranks, he dismounted and brought in a Russian prisoner. He also on the same day saved the life of Private Gardner, whose leg was fractured by a round shot, by carrying him to the rear from under a heavy cross fire, and from a spot immediately afterwards occupied by Russians.

Officers and men vied with each other in the performance of gallant deeds. Major Howard Elphinstone, of the Royal Engineers, exhibited his fearless nature by volunteering, on the night of the 18th June, after the unsuccessful attack on the Redan, to command a party of volunteers, who proceeded to search for and bring back the scaling-ladders left behind after the repulse; a task he succeeded in performing. He also conducted a persevering search close to the enemy for wounded men, twenty of whom he rescued and brought back to the trenches.

Lieutenant Gerald Graham, on the same day, several times sallied out of the trenches, in spite of the enemy’s fire, and brought in wounded men and officers.

On that day, also, when assaulting the Redan, Colour-sergeant Peter Leitch first approached it with ladders, and then tore down gabions from the parapet, and placed and filled them so as to enable those following to cross over. This dangerous occupation he continued till disabled by wounds.

Sapper John Perie was on that day conspicuous for his valour in leading the seamen with ladders to storm the Redan. He also rescued a wounded man from the open, though he had himself just been wounded by a bullet in his side.

Private John Connors, 3rd Foot, distinguished himself at the assault of the Redan, on the 8th September, in personal conflict with the enemy. Seeing an officer of the 30th Regiment surrounded by Russians, he rushed forward to his rescue, shot one and bayoneted another. He was himself surrounded, when he spiritedly cut his way out from among them.

Few surpassed Lieutenant William Hope, 7th Fusiliers, in gallantry. After the troops had retreated, on the 18th June, Lieutenant Hope, hearing from Sergeant Bacon that Lieutenant and Adjutant Hobson was lying outside the trenches, went out to look for him, accompanied by Private Hughes, and found him lying in an old agricultural ditch running towards the left flank of the Redan. He then returned, and got some more men to bring him in. Finding, however, that he could not be removed without a stretcher, he ran back across the open to Egerton’s pit, where he procured one; and in spite of a very heavy fire from the Russian batteries, he carried it to where Lieutenant Hobson was lying, and brought in his brother officer in safety. He also, on the 8th of September, when his men were drawn out of the fifth parallel, endeavoured, with Assistant-Surgeon Hale, to rally them, and remained to aid Dr Hale, who was dressing the wounds of Captain Jones, 7th Foot, who lay dangerously wounded. Dr Hale’s bravery was conspicuous; for after the regiment had retired into the trenches, he cleared the most advanced sap of the wounded, and aided by Sergeant Fisher, 7th Royal Fusiliers, under a very heavy fire, carried several wounded men from the open into the sap.

Private Sims, 34th Regiment, showed his bravery and humanity on the 18th June, when the troops had retired from the assault on the Redan, by going into the open ground outside the trenches, under a heavy fire, in broad daylight, and bringing in wounded soldiers.

Major Elton, 55th Regiment, exhibited the greatest courage on several occasions. On the night of the 4th August he commanded a working party in the advanced trenches in front of the Quarries; and when, in consequence of the dreadful fire to which they were exposed, some hesitation was shown, he went into the open with pick and shovel, and by thus setting an example to his men, encouraged them to persevere. In March, he volunteered with a small body of men to drive off a body of Russians who were destroying one of the British new detached works, and not only succeeded in so doing, but took one of the enemy prisoner.

Colour—Sergeant G. Gardiner, 57th Regiment, showed great coolness and gallantry on the occasion of the sortie of the enemy, 22nd March, when he was acting as orderly sergeant to the field officers of the trenches, in having rallied the covering parties which had been driven in by the Russians, and thus regaining and keeping possession of the trenches. Still more conspicuous was his conduct on the 18th June when attacking the Redan. He remained and encouraged others to stay in the holes made by the explosion of shells, from whence, by making parapets of the dead bodies of their comrades, they kept up a continuous fire until their ammunition was exhausted, thus clearing the enemy from the parapet of the Redan. This was done under a fire in which nearly half the officers and a third of the rank and file of the party of the regiment were placed hors de combat.

Major Lumley, 97th Regiment, especially distinguished himself at the assault on the Redan, 8th September. He was among the first inside the works, when he was immediately engaged with three Russian gunners, reloading a field-piece, who attacked him. He shot two of them with his revolver, when he was knocked down by a stone which for the moment stunned him. On his recovery he drew his sword, and was in the act of cheering on his men, when he received a ball in his mouth, which wounded him most severely.

Sergeant Coleman, also of the 97th Regiment, exhibited coolness and bravery unsurpassed, when, on the night of 30th August, the enemy attacked a new sap and drove in the working party. He, however, remained in the open, completely exposed to the enemy’s rifle-pits, until all around him had been killed or wounded; then, taking on his shoulder one of his officers, mortally wounded, he retreated with him to the rear.

Of the many anecdotes of heroism exhibited during the war, none is more worthy of note than one told of Ensign Dunham Massy, of the 19th Regiment, then one of the youngest officers in the army. At the storming of the Redan he led the grenadier company, and was about the first of the corps to jump into the ditch, waving his sword, and calling on his men to follow. They nobly stood by him, till, left for two hours without support, and seized by a fear of being blown up, they retired. He, borne along, endeavoured to disengage himself from the crowd, and there he stood, almost alone, facing round frequently to the batteries, with head erect, and with a calm, proud, disdainful eye. Hundreds of shots were aimed at him, and at last, having succeeded in rallying some men, and leading them on up the side of the ditch, he was struck by a shot and his thigh broken.

Being the last, he was left there with many other wounded. Hours passed by—who can tell the agony suffered by that mass of wounded men! Many were groaning, and some loudly crying out. A voice called faintly at first, and at length more loudly, “Are you Queen Victoria’s soldiers?” Some voices answered, “I am! I am!”

“Then,” said the gallant youth, “let us not shame ourselves; let us show these Russians that we can bear pain as well as fight like men.” There was a silence as of death; and several times, when the poor fellows again gave way to their feelings, he appealed to them in a similar strain, and all was silent.

The unquailing spirit of the young hero ruled all around him. As evening came on, the Russians crept out of the Redan, and plundered some of the wounded—though, in some cases, they exhibited kind feelings, and even gave water. Men with bayonets fixed strode over Massy’s body. Sometimes he feigned death. A man took away his haversack. A Russian officer endeavoured to disengage his sword, which he still grasped; nor would he yield it. The Russian, smiling compassionately, at length left him. When the works were blown up in the night by the retreating Russians, his left leg was fearfully crushed by a falling stone. He was found in the morning by some Highlanders, and brought to the camp more dead than alive from loss of blood. Great was the joy of all at seeing him, as it was supposed that he was killed. In spite of his dangerous wounds, he ultimately recovered.

Privates and non-commissioned officers vied with each other in acts of gallantry and dash, as well as of coolness and calm heroism.

Privates Robert Humpston and Joseph Bradshaw, Rifle Brigade, 2nd battalion, especially exhibited their cool bravery. A Russian rifle-pit situated among the rocks overhanging the Woronzoff road, between the third parallel right attack and the Quarries, was occupied every night by the Russians, much impeding a new battery being erected by the British. These two men, seeing the importance of dislodging the enemy, at daybreak of the 22nd April started off of their own accord, made so furious an attack on the astonished Russians that they killed or put to flight all the occupants of the rifle-pit, and held it till, support coming, it was completely destroyed.

Private B. McGregor, also of the same corps, finding that there were two Russians in a rifle-pit who considerably annoyed the troops by their fire, he, being in the advanced trenches, crossed the open space under fire, and taking cover under a rock, dislodged them, and took possession of the pit, whence he fired on the enemy.

Several of the officers, too, of the Rifle Brigade exhibited conspicuous gallantry. At the battle of Inkerman, Brevet-Major the Honourable Henry H. Clifford led a dashing charge of his men against the enemy, of whom he killed one and wounded another; and one of his men having fallen near him, he defended him against the Russians, who were trying to kill him, and carried him off in safety.

Lieutenant Claude T. Bouchier and Lieutenant William J. Cuninghame highly distinguished themselves at the capture of the rifle-pits, on the 20th of November 1854.

There were numerous instances in which, at the risk of their own lives, both officers and men saved the lives of their comrades who lay wounded in exposed positions. Private John Alexander, 19th Regiment, after the attack on the Redan on the 18th of June, knowing that many wounded men lay helpless on the ground, in spite of the storm of round shot, bullets, and shells still raging, went out from the trenches, and, with calm intrepidity, brought in, one after the other, several wounded men. He also, being one of a working party, on the 6th of September 1855, in the most advanced trench, hearing that Captain Buckley, of the Scots Fusilier Guards, was lying dangerously wounded, went out under a very heavy fire, and brought him safely in. Sergeant Moynihan, of the same regiment, also rescued a wounded officer near the Redan, under a very heavy fire; and on the assault of the Redan, 8th of September 1855, actually encountered, and with his own hand was seen to have killed, five Russians in succession. Other acts of gallantry are recorded of this brave soldier, who, as a reward for them, and for a long-continued career of excellent conduct, has been since deservedly promoted to a lieutenancy, and subsequently obtained his company in the 8th Foot.

Sergeant William McWheeney, 44th Regiment, showed probably as much bravery in saving the lives of his comrades, and in other ways, as any man in the army. At the commencement of the siege he volunteered as a sharpshooter, and was placed in charge of a party of his regiment, who acted as sharpshooters. In the action on the Woronzoff road, the Russians came down in such overwhelming numbers that the sharpshooters were repulsed from the Quarries in which they had taken post. On that occasion Private John Kean, one of his party, was dangerously wounded, and would have been killed, had he not, running forward under a heavy fire, lifted the man on his back, and borne him off to a place of safety. On the 5th of December 1854 he performed a similar act. Corporal Courtenay, also a sharpshooter, was, when in the advance, severely wounded in the head. Sergeant McWheeney then lifted him up, and, under a heavy fire, carried him to some distance. Unable to bear him farther, he placed him on the ground; but, refusing to leave him, threw up with his bayonet a slight cover of earth, protected by which the two remained till dark, when he brought off his wounded companion. He also volunteered for the advanced guard of Major-General Eyre’s brigade, in the Cemetery, on the 18th of June 1855. During the whole war he was never absent from duty.

Private McDermot, also, at the battle of Inkerman, seeing Colonel Haly lying wounded on the ground, surrounded by Russians about to despatch him, rushed to his rescue, killed the man who had cut down the colonel, and brought him off.

In like way, at the same time, Private Beach, seeing Lieutenant-Colonel Carpenter lying on the ground, several Russians being about to plunder and probably kill him, dashed forward, killed two of them, and protected the colonel against his assailants, till some men of the 41st Regiment coming up put them to flight.

Sergeant George Walters, 49th Regiment, also highly distinguished himself at Inkerman, by springing forward to save Brigadier-General Adams, who was surrounded by Russians, one of whom he bayoneted, and dispersed the rest.

Captain Thomas Esmonde especially exhibited his courage and humanity in preserving the lives of others. On the 18th of June he was engaged in the desperate and bloody assault on the Redan. Unwounded himself, he repeatedly returned, under a terrific fire of shell and grape, to assist in rescuing wounded men from the exposed positions where they lay. Two days after this, he was in command of a covering party to a working party in an advanced position. A fire-ball, thrown by the enemy, lodged close to them. With admirable presence of mind, he sprang forward and extinguished it before it had blazed up sufficiently to betray the position of the working party under his protection. Scarcely had the ball been extinguished, than a murderous fire of shell and grape was opened on the spot.

Lance-Sergeant Philip Smith, on the 18th June, after the column had retired from the assault, repeatedly returned under a heavy fire, and brought in his wounded comrades.

Several acts of coolness, similar to that recorded of Captain Esmonde, were performed.

On the 2nd September, Sergeant Alfred Ablet, of the Grenadier Guards, seeing a burning shell fall in the centre of a number of ammunition cases and powder, instantly seized it, and threw it outside the trench. It burst as it touched the ground. Had it exploded before, the loss of life would have been terrific.

Private George Strong, also, when on duty in the trenches, threw a live shell from the place where it had fallen to a distance.

Corporal John Ross, of the Royal Engineers, exhibited his calmness and judgment, as well as bravery, on several occasions. On the 23rd of August 1855 he was in charge of the advance from the fifth parallel right attack on the Redan, when he placed and filled twenty-five gabions under a very heavy fire, and in spite of light-balls thrown towards him. He was also one of those who, in the most intrepid and devoted way, on the night of the memorable 8th September, crept to the Redan and reported its evacuation, on which it was immediately occupied by the British.

Corporal William Lendrim, of the same corps, also, on the 11th April, in the most intrepid manner, got on the top of a magazine, on which some sandbags were burning, knowing that at any moment it might blow up. He succeeded in extinguishing the fire. On the 14th of February, when the whole of the gabions of Number 9 battery left attack were capsized, he superintended 150 French chasseurs in replacing them, under a heavy fire from the Russian guns. He likewise was one of four volunteers who destroyed the farthest rifle-pits on the 20th April.

Sergeant Daniel Cambridge, Royal Artillery, was among those who gallantly risked his own life to save those of his fellow-soldiers. He had volunteered for the spiking party at the assault on the Redan, on the 8th of September, and while thus engaged he was severely wounded; still he refused to go to the rear. Later in the day, while in the advanced trench, seeing a wounded man outside, in front, he sprang forward under a heavy fire to bring him in. He was in the open, shot and shell and bullets flying round him. He reached the wounded man, and bore him along. He was seen to stagger, but still he would not leave his helpless burden, but, persevering, brought him into the trench. It was then discovered that he had himself been severely wounded a second time.

The gallantry of Sergeant George Symons was always conspicuous, but especially on the 6th of June 1855, when he volunteered to unmask the embrasures of a five-gun battery, in the advanced right attack. No sooner was the first embrasure unmasked, than the enemy commenced a terrific fire on him; but, undaunted, he continued the work. As each fresh embrasure was unmasked, the enemy’s fire was increased. At length only one remained, when, amid a perfect storm of missiles, he courageously mounted the parapet, and uncovered the last, by throwing down the sandbags. Scarcely was his task completed when a shell burst, and he fell, severely wounded.

Driver Thomas Arthur, of the same corps, had been placed in charge of a magazine, in one of the left advanced batteries of the right attack, on the 7th of June, when the Quarries were taken. Hearing that the 7th Fusiliers were in want of ammunition, he, of his own accord, carried several barrels of infantry ammunition to supply them, across the open, exposed to the enemy’s fire. He also volunteered and formed one of the spiking party of artillery at the assault on the Redan.

Among the numberless acts of bravery performed at the battle of Inkerman, few are more worthy of record than one performed by Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Charles Russell, Bart., of the Grenadier Guards. The Sandbag battery, the scene of so many bloody encounters during that eventful day, had been at length entered by a strong party of Russians, its previous defenders having been killed or driven out by overwhelming numbers. Sir Charles Russell, seeing what had occurred, offered to dislodge the enemy, if any men would accompany him. The undertaking seemed desperate; but notwithstanding this, Sergeant Norman and Privates Anthony Palmer and Bailey immediately volunteered; others afterwards followed their example. On they went, following the gallant Sir Charles at furious speed, and into the battery they rushed. Bailey was killed, but Palmer escaped, and was the means of saving his brave leader’s life. The Russians were driven out, and the battery was held by the British.

Sir Charles Russell received the Victoria Cross. We now give an extract from a letter he wrote to his mother after the battle: “After the brave band had been some time in the battery, our ammunition began to fail us, and the men, armed with stones, flung them into the masses of Russians, who caught the idea, and the air was thick with huge stones flying in all directions; but we were too much for them, and once more a mêlée of Grenadiers, Coldstreams, and Fusiliers held the battery their own, and from it, on the solid masses of the Russians, still poured as good a fire as our ammunition would permit. There were repeated cries of ‘Charge!’ and some man near me said, ‘If any officer will lead us, we will charge’; and as I was the only one just there, I could not refuse such an appeal, so I jumped into the embrasure, and waving my revolver, said, ‘Come on, my lads; who will follow me?’ I then rushed on, fired my revolver at a fellow close to me, but it missed fire. I pulled again, and think I killed him. Just then a man touched me on the shoulder, and said, ‘You was near done for.’ I said, ‘Oh no, he was some way from me.’ He answered, ‘His bayonet was all but into you when I clouted him over the head.’ And sure enough, a fellow had got behind me and nearly settled me. I must add, that the grenadier who accompanied me was publicly made a corporal on parade next morning. His name is Palmer. I did not know it, but I said, ‘What’s your name? Well, if I live through this, you shall not be forgotten.’”

Corporal Shields, 23rd Regiment Royal Welsh Fusiliers, among many brave men especially distinguished himself, and he was among the earliest recipients of the order of valour. He received also the Cross of the Legion of Honour from the Emperor of the French for the following brave action:—

On the 8th of September 1855 he was among the foremost at the desperate attack on the Redan, and one of the very few who reached the ditch at the re-entering angle. Finding that Lieutenant Dyneley, adjutant of the regiment, for whom he had a great regard, had not returned, he immediately set forward by himself to search for him, exposed to the hot fire of the enemy, who, although they must have known that he was on an errand of mercy, continually aimed at him. After searching for some time, he found his young officer on the ground, desperately wounded, behind a rock, which somewhat sheltered him from the enemy’s fire. Stanching the flow of blood as well as he could, he endeavoured to lift him on his back to carry him to the trenches, but the pain of being lifted in that way was more than Mr Dyneley could bear. Reluctantly he was compelled to relinquish the attempt; and hurrying back to the trenches, he entreated one of the medical officers to render the young officer assistance. His appeal was not made in vain. Without hesitation, the brave Assistant—Surgeon Sylvester, always ready at the call of humanity, volunteered to accompany him. Together they passed across the hailstorm of bullets the Russians were incessantly sending from their walls, when the surgeon knelt down and dressed the wounds of his brother officer, and did all that he could to alleviate his sufferings. Unwillingly they quitted him that they might obtain more succour; and in the evening Captain Drew and other volunteers accompanied Corporal Shields, who then for the third time braved the bullets of the enemy, and together they brought in the young lieutenant. Unhappily, his wound was mortal, and he died that night. While praising the brave corporal, we must not forget the heroism of the young surgeon. For this action Corporal Shields was rewarded with a commission.

Major Gerald Littlehales Goodlake, Coldstream Guards, gained the Victoria Cross for his gallantry on several occasions. A number of the best marksmen in each regiment had been selected to act as sharpshooters. With a party of these he set forth, on a night in November 1854, towards a fort at the bottom of the Windmill ravine, where a picket of the enemy were stationed. Approaching with all the caution of Indian warriors along a difficult and dangerous path, they suddenly sprang on the astonished Russians, who took to flight, leaving their rifles and knapsacks behind. A short time before this, on the 28th of October, he was posted in this ravine, which, with the party of his men, not exceeding thirty, he held against a powerful sortie of the Russians, made against the 2nd division of the British army.

In truth, young officers brought up in luxury and ease vied with soldiers long accustomed to warfare and the roughest work in deeds of daring and hardihood.

These are only some few of the many acts of heroism, coolness, and gallantry performed during the war, and for which the Victoria Cross has been awarded. Undoubtedly many more were performed, which have not been noted, in consequence of the death of the actors or witnesses, and some gallant men, though equally deserving, have not brought forward their claims; but even from the few examples here given, it is shown of what materials the British soldier is formed.

(Go back to previous chapter)