Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Lectures on the Ecclesiastical History of First and Second Centuries, by Frederick Denison Maurice (published 1854).

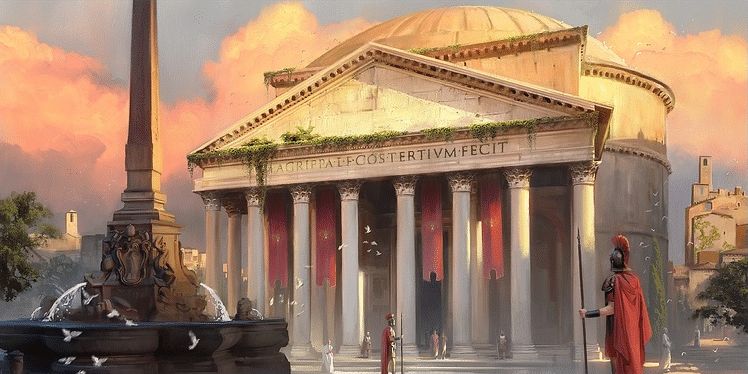

….We talk familiarly, in an off-hand way, of the Church and the world. Oftentimes we attach to the world the notion of a society which is pursuing secular objects and neglecting religion; we think of the Church, as a society which is despised for being too religious—because it cares chiefly for divine exercises—because it exaggerates the sacredness of public services — because it cultivates in its interior circle a transcendent morality and purity. If you apply these maxims to the second century, you will make a very great mistake indeed. The people in Antioch and Alexandria were sensual and corrupt enough; they pursued secular objects, money and pleasure, as men do here—more systematically, perhaps, with far fewer restraints of opinion—but they were not irreligious. Religion formed one of their regular formal occupations; it entered into all their occupations; it was connected with most of their amusements; it blended with every part of their local polity. Each city had its own peculiar gods, priests, sacrifices, festivals, which it had inherited from former days, and to which it clung as its most proper and native characteristic; the sign that it was a city of the past, though its civil freedom was gone, and though it was merged in the great empire. Then every part of the imperial system was religious. The Jupiter of the Capitol was still acknowledged as the power which held the state together. The Pantheon, with him as its centre, was capable of a continual expansion; it did actually expand to meet every new emergency, to take in each new form of worship that had prevailed in any of the conquered tribes. But the Roman gods still retained their own ascendency; they were incorporated into the history of the land. The institution of their priests—the reasons for the sacrifices that were offered to them—formed a principal element in the narratives which reminded the people of their greatness, and in what way their forefathers achieved it. The life of the particular families which composed the state, and whose deeds had made it illustrious, were associated with traditions of the gods; the images of the great men, which their descendants preserved and contemplated, could not be separated from the images of the household deities. The more you read, the more you will perceive how auguries, divinations, and sacrifices, were worked into the whole tissue of social life at that time. It is true that the faith of the people at large had grown weaker; they were not the least sure whether the gods heard them, or even whether there were gods to hear. But they did not forego their devotions for this scepticism. Their actual sorrows, individual and political, were not less than they had been; the stings of conscience were not less. Something must be done to obtain comfort and relief, even if it was done in desperation. It was judicious therefore, they thought, as well as natural, to adhere to the old rites. They were performed more in fear than before, more to avert the anger of evil powers; but they were performed. And if the nature of other powers that were worshipped was uncertain, the power of the emperor was indisputable. The gods had assuredly delegated their authority to him; his name must be sworn by; to his image must sacrifices, with all fear and observance, be presented; not to do so was to violate the duty of a citizen, which in this, as in all things else, was dependent upon religion, and could in no way be disengaged from it.

Nor must you forget the fact to which I have so often alluded, that besides the vast religious machinery of the Roman world, there were flying about in all directions men who made light of mere machinery, and appealed to the sense in our hearts of hidden powers, which may act upon us suddenly for good or for mischief, which may affect our souls or our bodies, which may restore health or throw us into sickness, which may give us marvellous intimations of terrible or fortunate events that have befallen or are to befall individuals or states. If you leave the enchanters, auguries, prophets, of Jewish or heathen origin, out of your calculation, when you are trying to understand the world of the second century, you will have a very imperfect conception of it. These men had all the influence which those possess in all ages who are supposed not to be bound by the rules and terms of an organized community—to have a secret illumination and divine afflatus; and yet, on the other hand, there was a method in all their madness. Many of them possessed real knowledge; they addressed themselves to undoubted instincts, fears, hopes, in their fellow-creatures; and having shaken off to a great extent the sense of moral obligation, they could turn these to account fearlessly. The speculators and gold-seekers of the age had long discovered that inspirations might be made a regular and profitable branch of trade.

And if this was the world, what was the Church? In the eyes of their heathen neighbours, its members were an utterly godless race. The name which the people of Smyrna gave them, when they called for vengeance on Polycarp, was the name they bore everywhere. They were the Atheists. A people without images, who frequented no temples, who offered no sacrifices—what could it mean? Yet a people who evidently had a fellowship—a strong, close organization—who were intimately bound together with each other in each city, who held evidently some strange bond of intimacy with those in distant cities! What could go on in those private meetings of theirs? It was impossible that they should not have some sacrifices. Words had been heard from them which seemed to signify that they thought much of sacrifice—nay, of a human sacrifice. Horrors, no doubt, not to be spoken of, were enacted in their late and early assemblies. Some affirmed that they devoured human victims. What a small step was it from that charge, to suppose that those victims were their own children! Intelligent men, like Trypho, might not attach much weight to these reports; men with great opportunities of information, like Pliny, might almost know that they were groundless. But Trypho was as much scandalized as any one could be, by what seemed to be the Christians’ neglect of all the ceremonies, which, if they believed the Jewish Scriptures, they ought to practise. However harmless the meetings before sunrise might be, which Pliny heard of from the tortured servants, the “superstition,” nevertheless, seemed to him exitiabilis; for it was secret—it had the signs of a conspiracy—it was like no other; it undermined the religion of the empire. However paltry might be its exercises, or its apparent instruments, it had a power which could not be overlooked, which was affecting all classes and conditions of Trajan’s subjects.

How was this power put forth? How did it make itself felt? I can only answer the question by referring to the name into which those who seemed Atheists to the Polytheists of the world around them were baptized. Their baptism declared that they confessed a Father. The name was no new one to the population in the midst of which they were dwelling. It was familiar to Greeks. Homer had spoken continually of the Father of gods and men. Romans, who had adopted Greek poetry and mythology, had yet deeper associations with the name than they had. It was connected with their domestic hearth, with a multitude of old thoughts,—sadly worn out, but never lost,—of which that hearth had been the centre; with the polity which had been based on the reverence for fathers. Think of such convictions as these ringing in the ears of Greeks and Romans: “The Father of all has spoken to us. His name is not a mere name. He has emancipated us from our slavery to visible things; He has actually claimed and adopted us as His children.” Think, I say, of such words uttered in the ears of men who were crushed under a weight of religious rites and observances, who felt they had no hold on any living being in heaven or earth, or under the earth, yet who felt that there was some God, to whom all other gods owed obedience, and before whom men were to tremble. But, then, add that these were not mere words—that all the language and institutions of those who spoke them had this name of Father at their basis—and you will understand something of the charm with which they worked. If you ask me how they made their point good—how they proved to people that they had a right to call themselves children of God—I can give you a very poor answer, and I am not sure that theirs would have been much better. Their attempts at proofs and evidences were very numerous, sometimes very ingenious; they could fetch them from Scripture and from nature, from types and from plain history. There were precious grains of wheat in their arguments, but I am forced to express my conviction that there was also much chaff; and I feel confident that it was not the best arguments or the worst which influenced the hearts of heathens or of Jews. It was the Gospel— “There is such a Father for you,” speaking to those who had need of one, and were craving for one—which was immeasurably mightier than all the authorities by which it was supported, and which imparted its own momentum to those that had least force of their own. Those argued best who were most conscious of this truth; those who could not argue at all, broke down strong-holds more effectually by their lives and their deaths.

Here, then, was the first great engine that undermined that vast polytheistic world which I have described to you. The Jews, who protested against the Christians as deserters to a Nazarene impostor, asked why they could not stop here? Was not the declaration of a One God the all-sufficient protest against many gods? If that was all that the Church had said, no doubt it had merely repeated what the synagogue had been saying for so long, and saying not altogether in vain—for its testimony had been one of the great powers which had shaken the faith of heathenism,—but certainly without establishing a faith, or effecting any great moral change in the condition of the world. To speak of a Father was not the same thing as to speak of a One God; heathens as much as Christians felt that it was not. The difference is the turning point of the most perplexing questions of the second century. Το understand those questions, you must fix your minds resolutely upon it—still more, to understand the effect which the Church actually produced. The simplest and bravest men lifted up their voices to proclaim a Creator of heaven and earth. Only so far as they made that proclamation, could they rescue men from the worship of things in heaven and earth. When they made it thoroughly and boldly, they were able to look upon nature with clear and joyful eyes; to speak of its peace and harmony as the Roman Clemens does in that extract I read to you,—an extract which is a specimen of a number of passages that occur in the writers of this century. Their eyes were often opened to see a beauty and order in the world, which had been hidden even from the most graceful and accomplished thinkers of the old time. But this illumination came from their belief: “Our Father is the Creator of heaven and earth. We are not a part of these things which we look upon; we are above them. We belong to another economy; we are citizens of His kingdom, members of His family.”

And, therefore, it was inevitable that the Church should utter the second Name in its baptismal formula, if there was to be any meaning and power in the first. Was it enough for them to say, “We have a Father, for a great Prophet and Teacher has come down from heaven to teach us?” By speaking thus, would they have broken the chains which bound the necks of the heathens around them? would they have brought about any fellowship among those who were divided by places and traditions? The people about them believed in a multitude of dæmons, demigods, sons Demigods, of the gods—beings who connected together earth and heaven—rulers of cities, who were also rulers of sun, or of moon, or of stars. They believed in intellectual powers and moral virtues, as well as in powers of darkness and evil, which they clothed with forms. What teacher or prophet could rise above all this complicated machinery? what exchange would he have been for all these messengers and mediators? The thought of them was a burden upon the spirit; they were masses of clouds which darkened the heaven, and hid the face of God; but they had grown up out of the wants of the human heart, and however feeble, and unsatisfactory, and burdensome they were, the heart must cling to them till it found a substitute for them. When the members of the Church spoke of an only-begotten Son of God—of a living Word, who was the Lord of men’s spirits and the Lord of angels, in whom the mind and will of the Father uttered itself to His creatures, in whom He acknowledged them as His children—this substitute was provided. This news shook not earth only, but also heaven. It did not encounter one of the popular schemes of worship, but all of them. It encountered them, not by taking away anything from the heart on which it had rested, but by showing it what it had to rest upon; how it had been seeking at a distance for that which was at home; how it had been building castles and prisons from fragments of the Rock upon which God had built His universe.

But how was this Divine Son, this eternal Word, connected with the poor, miserable, sinful creatures to whom He was proclaimed? This, as you have seen, was the second of the great puzzles by which the minds of men in the second century were perplexed. All the great questions and controversies of the time were involved in the question, whether they might really identify this Divine Word with Jesus, the Man of sorrows, who had died upon the cross. We have seen how some of the debates on this subject were conducted; we shall have to return to them again. What I am speaking of now is the power which the Church exercised on the surrounding world; and this power, I conceive, was greater or smaller in proportion to the strength or weakness with which she asserted the position that the Son of God had actually taken human flesh, and suffered under Pontius Pilate, and been crucified, dead, and buried. Where that message was proclaimed broadly and nakedly, all the schemes by which men had sought to make their way from earth to heaven—to bring the gods into peace and reconciliation with men, to avoid the penalties of evil, to escape from the conscience of it—were supplanted by the one great doctrine and fact, that a reconciliation had been made between God and His creatures, that He had made peace with them. The condition of humanity was placed upon a new ground, for a Son of man had been revealed. Whatever might have been its condition, He was now declared to be its centre and its root.

But this testimony of reconciliation, mighty as it was, would have been utterly ineffectual without that one which the Apostles had borne at first, which they were sent forth to bear, which was the characteristically Christian testimony. “Christ is risen!” was the altogether amazing and monstrous proclamation which sounded in the ears of a scoffing, exhausted, lazy generation,―tired of miracles, hopeless of any blessing to themselves or the world,―from an insignificant body who were believed to be Atheists, and to eat the flesh of children. And yet, if the previous message were listened to, this must be received; not the authority of the teacher, but the conscience of the disciple, demanded that it should. The words of the Apostle, “It is not possible that He should be holden of death,” were the natural, necessary sequel to the announcement of the living Word, in whom all power dwelt, and yet who had humbled Himself, and submitted to the death of the cross. And so, amidst the multitudes who confessed dæmons to be great, and the emperor to be in some sense greater than the dæmons, but who positively knew that death was greater than the emperor, and was the tyrant of each of them, there went forth the actual news of a Conqueror of death, news which, if at first it was incredible, almost ridiculous, yet spoke to hearts that had been craving for it ever since they began to beat, and had an assurance within that it must be true, unless the whole universe was a lie. Their assurance of immortality had come to them in a thousand ways before. Every Tartarian and Elysian story bore as authentic tidings of it to the popular mind, as the inquiries of the most serious thinkers did to theirs. But the Church preached not of immortality, but of resurrection―not of the surviving of some particle of our nature, but of the resurrection of man―not of the resurrection of a man, but of the Son of man, of the Lover of men, of Him who had borne death for man. And yet if these acts done for men―this condescension to their misery―had been all, the perpetual longing in men to send up their thoughts and prayers to One above them would have been unsatisfied; the belief in a heaven, which had been the strongest, the most helpful to them of all―with whatever confusions it had been mingled, however it had cut them off from their gods―would have been extinguished. He is gone up on high to His Father―He lives to make intercession for us―was the great sequel to the message of resurrection. All who heard it felt that the first part of it would have been unmeaning without the second.

With these thoughts of immortality had been inseparably associated the witness of a separation between the right and the wrong doer; the dreams of Æacus and Rhadamanthus; the dim, hazy vision of fields in which the blessed wandered; the vision that rose not more distinctly, but far more frequently and naturally, before the conscious criminal, of a dark river, and groans, and solitude. How utterly ineffectual these anticipations were to produce morality, or to check crime, the open atrocities of the Roman world, which the sword of the magistrate, not the terrors of the priests, kept from being utterly destructive, not to speak of the stench of its more inward and secret corruptions, may sufficiently attest. The message of resurrection went forth in the second century, as it had done from St. Paul’s lips at Athens and before Felix, joined with the message of judgment. The Divine Word, the Lord of the hearts and reins of men, He who had come into the world to redeem them from their evil, knew what that evil was. He would bring it to light; whatever was done or spoken in darkness, would come out into the broad day. His voice would be heard by the whole creation; the dead as much as the quick would own it. To connect judgment with a Person―with an actual Discerner of thoughts and intents―with a Deliverer,―what a change was this from that old, worn-out apprehension of a world after death, which was so inoperative for morality, but upon which the religious scheme of the empire had by degrees established itself! When this trumpet was blown, the walls of the great Roman Jericho shook more than at almost any other sound. Had it been blown more strongly, they might have fallen down at once; for though such a prophecy of judgment was so new, it awakened the oldest and deepest convictions that had been slumbering in the spirits of men.

But the Gospel of a resurrection and of a judgment would have been unintelligible,—it would not have been a Gospel, because it would have come with no pledge of a new and higher life,—if the third name in the Christian covenant had been separated from the other two. You have heard how the news of a Spirit coming down to dwell among men was interwoven with all that our Lord did upon earth, with all that He spoke of a kingdom of heaven which was at hand. You have heard how the preaching of the resurrection, on the day of Pentecost, interpreted the sound of the rushing and mighty wind, and the cloven tongues of fire that sat upon the Apostles. You have heard how the gift of this Spirit created the Christian society out of the chaos of Jewish sects, changed the ministers and members of it from ignorant cowards into brave and wise men. But to understand the real power of the announcement that such a Spirit of truth, and unity, and power had come, you must think of it in connexion with that lying spirit by which the diviners and enchanters of the Roman world were possessed. I use that language deliberately. The teachers of the second century talked of evil spirits and diabolical possession. We often abuse their words to a superstitious meaning; it may often have had that meaning in their mouths. But the more one considers the horror of lying, the more one considers that those lies which connect themselves with the name of God are the most inward, essential, radical of all lies, that they are those which enter into the spirit of a man, and corrupt and destroy him, and that all outward lies of act and word are their progeny; the more one is compelled to talk of a spirit of lies, to talk of it as penetrating the habits and temper of an age, as coming forth in innumerable forms, but as concentrated in the religious impostors, in those who abuse spiritual influences and terrors to fleshly and earthly purposes. And the more simply one adheres to the language of Scripture in saying that the Spirit of truth, the Spirit of the Father, the Spirit with which Christ was anointed, is given to men to renew them in the spirit of their minds, to deliver them from the spirit of lies, to cast him out; the more we understand how it is possible that a man or a world should be regenerated. To oppose the Holy Spirit, the one uniting Spirit, to the unholy and dividing spirit which they saw working its portents all around them, was assuredly one chief part of the mission of the Church in this century—one which all its higher members understood that they were to fulfil.

But the Holy Spirit did not merely exorcise that which was unholy. He testified to those who yielded to Him, that they were members of a holy body. There could be no limits assigned to this body; it stood in Christ the eternal Word; the fetters of time and space had been broken down for it. The Christians knew inwardly that they were united to those who were separated from them by lands, seas, and death. In so far as they were partakers of God’s love, they had fellowship with all the creatures over whom that love extended.

But here the third great difficulty forced itself upon them. The Spirit separated them from the corrupt world by which they were hemmed in; He made them saints. They seemed brought into a narrower, smaller circle than other men—actually brought into it by the suspicions and hatred of Jews and heathens —spiritually and inwardly brought into it, in proportion as they acquired a disgust for the practices in which when Jews and heathens they took delight. And yet the effect of their union with Christ, of the power and indwelling of His divine Spirit, was to enlarge their hearts, to give them sympathies which they never had before—sympathies with that which is human—sympathies with the publicans and sinners, with whom their Lord conversed on earth, and for whom He died. Were they to be more exclusive than others, or wider, broader, more catholic?

Whether individuals could answer this question or not, the Church, so far as it carried on a successful war against heathenism, found the answer. That which undermined the divided, exclusive fellowships into which heathen worshippers were necessarily broken up—as worshippers of natural idols, as servants of local gods, as devoted to mere objects of sense—was the communion of saints. The discovery that this apparently narrow and separating body was really able to embrace all within its circle,—that it could not contract itself, without being false to its profession. The Church was feared so far as its members were united; so far as they held themselves separate from all contact with idols; so far as they were ready to embrace all idolaters. Herein lay the secret of that power which the world around trembled at,—herein the secret of the attraction which was continually bringing men from all quarters into the Christian circle.

But the force of this magnet would not have been felt by those who were drawing near to different altars, for the sake of getting some relief from the reproaches of conscience, if another had not been joined with it. The Christian Church could say boldly, “God for Christ’s sake has forgiven us.” It could invite men to lay the burden which was oppressing them before God. It could say, “This forgiveness is for you. The Spirit of forgiveness, who makes the heart guileless and loving, is for you. When God takes you as His children, He puts away your offences; and He promises that each day you shall receive that cleansing and renewal of heart—that inward restoration which you will more and more feel that you need.” What a blow was this one proclamation to the whole scheme of priestcraft, by which men had aimed at bringing Heaven to overlook the wrongs which they knew they had committed! What an assurance it was, not of ease in the evil, but of deliverance out of it!

Something more was needed still. For with bodies actually bowed down by sickness and anguish, it is not enough to be told of a deliverance that has been effected for their spirits; of a Spirit who unites those spirits to Christ and to each other. It is not enough to hear that Christ, the Son of God, has redeemed His own body from death. They need to be told that those bodies of theirs, which are groaning under a heavy and intolerable burden, shall be rescued from it; that they shall be delivered from disease and death. The power of the Spirit is not complete over the enemies of men, if this news cannot be declared to them. The Church uttered this promise, too, in the ears of men who were subject to this bondage. It said, “If the Spirit of Him who raised up Christ dwell in you, He shall also quicken your mortal bodies.” Nay, it spoke words deeper even than these—not perhaps as fully understood, but yet most necessary for those who had confessed death to be their master. It spoke of the Spirit as making men partakers of the eternal life which was with the Father, and which Christ had manifested.

I have been repeating, as you will have perceived, the principal articles in what we call the Apostles’ Creed, because I could not find any other way of telling you so well in what kind of armour it was that the Church in the second century fought, whenever she gained any victories. I do not care to prove that these were just the words or phrases in which she delivered her message. That it was the substance of her message, I think you will be convinced the more you read the different books to which I have referred you in former Lectures, and compare them together. There does occur in several of these books a form of words, very like our “I believe.” It is evidently put forth as the baptized man’s confession. People in later times were so puzzled to understand how the second century should have got such a creed, and how after centuries should have retained it, that they fell into the strangest fancies to explain the marvel. Some of the Christian writers had called it “an apostolical tradition.” Might it not then be asserted, that the Apostles had met together to construct it? that perhaps each Apostle had originated a clause? Might not Polycarp have had it from St. John? Might it not have been given as a deposit to all the Churches to keep? No Evangelist or Apostle, I need scarcely tell you, has given any account of a meeting for this purpose, though St. Luke does speak of two or three of the Apostles meeting to discuss the question of circumcision. A writer of the third century, the earliest of religious novelists,—a man who feigned the name of Clemens for a book which he called the “Recognitions,” —certainly introduces the twelve Apostles holding a disputation, and reports speeches which each of them made. But this audacious and profane, though far from stupid or ill-meaning romancer, merely used the lips of Apostles as instruments for giving currency to his sentiments; not one of the honester and wiser Fathers would have either ventured to assert the Apostolical Convocation as a fact, nor to introduce it into a fiction. The Creed, I think you will see, grew up in a much simpler and more natural manner. The apostolic tradition the Christian Church had: the baptismal formula was that tradition. The Church had the writings of the Apostles, who were sent forth with the commission to preach the name into which they baptized. The Church had the experience of heathen corruptions and heathen needs. And the Spirit of God was promised to them, to make the words which they had received, and all the experiences of others and of themselves, effectual to guide them into truth. If we want more than this, to show how they may have obtained this confession, we have not yet learned what an Ecclesia is, or why such a body has existed in our world.

Do not however suppose that a mere creed, if it were the best in the world, could have expressed divine principles to the members of the Church, or have made them effectual for subverting heathenism. The relations of men to God must utter themselves in prayer and praise. Any other language is imperfect language; it may give us the shell of a belief,—it cannot express the life and essence of it. If there had not been an “Our Father” as well as an “I believe,” the Church would have fared very ill in its battles with the world. There, the whole mystery of God’s revelation of Himself to His creatures is presumed in their invocation of Him. He has made them His children, therefore they speak to Him. That His Name may be hallowed by them, and known upon the earth, is the end for which He has called them, and for which they exist. But He must hallow that Name; they cannot, otherwise than as His instruments. They are sure that He has a kingdom in them, and a kingdom over the whole earth; they desire that His kingdom should come mightily in both. They know that His will is the right will—that there are those who obey it; they desire that their wills and all wills may be subdued to it. He has provided all things that man wants; they desire to bless Him for them, and to receive His gifts each day from His hand, and that all should share them together. They want that forgiveness which comes to them only while they forgive, and, therefore, the Spirit of forgiveness, which includes both blessings. They have a Tempter near them, and God only can keep them from him; there is evil within and without—He only can deliver them from it.

That this prayer was the root of all the prayers of the Church in the second century,—that they unfolded themselves out of it,—we have abundant evidence. Each clause in the prayer struck at the heart of some superstition that had enslaved human spirits,—at the great and cardinal superstition of all, that prayer, instead of coming from God, and being the creature’s act of sacrifice and submission to Him—its flight to Him from the evil that was oppressing it—was an effort to convert His will, to make Him favourable to avert the evil of which He was the author. This prayer converted everything else into an organ of prayer and thanksgiving. It threw back a light upon the old psalms, explaining the enemies with which David was struggling,—his confidence, his confessions, his cries to be judged,—his feeling that when he was praying, all Israel was praying with him; that when he was giving thanks, he was praising the Lord of the whole earth. It turned all the gifts of nature into excuses for praise, because they were not gifts of nature but of God. It found a necessity and encouragement to prayer in dungeons, fires, wild beasts.

You have heard how Polycarp prayed, not, as his Latin translator represents, for support to himself in his hour of peril, but for the whole Church and for all mankind. His sympathies expanded and became deeper as that hour approached which most men regard as separating them from others, and as obliging them to fix their thoughts upon themselves. Whence came the difference? I tried to indicate the cause of it when I was speaking of him and of Ignatius; but the subject is so important, and is so involved in the one of which I am speaking now, that I must present it to you from another side.

I have told you what the heathen world said of the Christians in reference to sacrifice. Sometimes they were thought to neglect sacrifice altogether; sometimes it was suspected that they offered sacrifices of the most monstrous kind. Evidently this was the point on which there was most difficulty in understanding them; this, therefore, was the test to which they were always brought: Would they offer sacrifices, or not? would they rather be sacrificed themselves than do it? The answer was distinct:

‘We cannot offer your sacrifices; we choose to be sacrifices ourselves. For the great human Sacrifice has been offered; it is upon that we feed in those secret meetings you speculate about. We believe that Sacrifice to have been offered for the whole world; therefore it is our right and privilege to offer ourselves as sacrifices to God.’

I want you to connect these three things in your mind: the heathen sacrifices which each man was to offer, to make the gods propitious to him; the Christian declaration that the Sacrifice had been offered once for all, and that by it God had reconciled the world to Himself; and the belief of the Christian man, that his own death was a sacrifice which God had prepared, and which He would accept for the sake of His Son. Then, I think, you will understand why Polycarp was not thinking of his own death, but of Christ’s death at that time, and, because of Christ’s death, therefore, of all everywhere for whom He died. And then, I think, you will further understand what was and must have been the centre of all Christian worship, in order that it might carry out the principle and meaning of the Lord’s Prayer. There are many differences of statements about the liturgies of this time; but the most learned antiquarians, and scholars of different nations and different schools, seem to be agreed on this point; the The Eucharist was the centre of the worship; everything was referred to that. Thanksgiving and praise for a complete and accepted sacrifice, a sacrifice for the sins of the whole world, was at the root of all devotion and all praise: everything was included and gathered up in that service. There was the highest utterance of praise and thanksgiving, there was the lowliest confession and humiliation; there they sought the power to act and to suffer; there they learnt that to make an oblation of themselves, was not to do a great act in order to win a great prize, but was itself the highest gift and prize that God could bestow on them,—a participation in the life and death of His Son. Therefore, of all the weapons in the Christian armoury with which they shattered the old gods, and those who served them and burnt incense to them, this, I conceive, was the most powerful, at least it was that which explained the purpose and direction of all the rest.