Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Fifty-two Stories of the British Navy, from Damme to Trafalgar, edited by Alfred H. Miles (published 1897). All spelling in the original.

Early in the year 1798 Sir Horatio Nelson hoisted his flag on board the Vanguard, and was ordered to rejoin Earl St. Vincent.

Immediately on his rejoining the fleet, he was despatched to the Mediterranean, with a small squadron, in order to ascertain, if possible, the object of the great expedition which at that time was fitting out, under Bonaparte, at Toulon. The defeat of this armament, whatever might be its destination, was deemed by the British government an object paramount to every other; and Earl St. Vincent was directed, if he thought it necessary to take his whole force into the Mediterranean, to relinquish, for that purpose, the blockade of the Spanish fleet, as a thing of inferior moment; but, if he should deem a detachment sufficient, “I think it almost unnecessary,” said the first lord of the Admiralty, in his secret instructions, “to suggest to you the propriety of putting it under Sir Horatio Nelson.” It is to the honour of Earl St. Vincent that he had already made the same choice.

The armament at Toulon consisted of thirteen ships of the line, seven forty-gun frigates, with twenty-four smaller vessels of war, and nearly two hundred transports. Nelson sailed from Gibraltar on May 9th, with the Vanguard, Orion, and Alexander, seventy-fours; the Caroline, Flora, Emerald, and Terpsichore frigates; and the Bonne Citoyenne sloop of war, to watch this formidable armament. On the 19th, when they were in the Gulf of Lyons, a gale came on from the north-west. It moderated so much on the 20th, as to enable them to get their top-gallant masts and yards aloft. After dark, it again began to blow strong; but the ships had been prepared for a gale, and therefore Nelson’s mind was easy. Shortly after midnight, however, his main-top mast went over the side, and the mizen-top mast soon afterward. The night was so tempestuous, that it was impossible for any signal either to be seen or heard; and Nelson determined, as soon as it should be daybreak, to wear, and scud before the gale: but, at half-past three the foremast went in three pieces, and the bowsprit was found to be sprung in three places.

When day broke, they succeeded in wearing the ship with a remnant of the spritsail: this was hardly to have been expected. The Vanguard was at that time twenty-five leagues south of the islands of Hieres, with her head lying to the north-east, and if she had not wore, the ship must have drifted to Corsica. Captain Ball, in the Alexander, took her in tow, to carry her into the Sardinian harbour of St. Pietro. Here, by the exertions of Sir James Saumarez, Captain Ball, and Captain Berry, the Vanguard was refitted in four days; months would have been employed in refitting her in England.

The delay which was thus occasioned was useful to him in many respects: it enabled him to complete his supply of water, and to receive a reinforcement, which Earl St. Vincent, being himself reinforced from England, was enabled to send him. It consisted of the best ships of his fleet: the Culloden, seventy-four, Captain T. Trowbridge; Goliath, seventy-four, Captain T. Foley; Minotaur, seventy-four, Captain T. Louis; Defence, seventy-four, Captain John Peyton; Bellerophon, seventy-four, Captain H. D. E. Darby; Majestic, seventy-four, Captain G. B. Westcott; Zealous, seventy-four, Captain S. Hood; Swiftsure, seventy-four, Captain B. Hallowell; Theseus, seventy-four, Captain R. W. Miller; Audacious, seventy-four, Captain Davidge Gould. The Leander, fifty, Captain T. B. Thompson, was afterwards added. These ships were made ready for the service as soon as Earl St. Vincent received advice from England that he was to be reinforced. As soon as the reinforcement was seen from the masthead of the admiral’s ship, off Cadiz Bay, signal was immediately made to Captain Trowbridge to put to sea; and he was out of sight before the ships from home cast anchor in the British station. Trowbridge took with him no instructions to Nelson as to the course he was to steer, nor any certain account of the enemy’s destination: everything was left to his own judgment. Unfortunately, the frigates had been separated from him in the tempest, and had not been able to rejoin: they sought him unsuccessfully in the Bay of Naples, where they obtained no tidings of his course, and he sailed without them.

The first news of the enemy’s armament was, that it had surprised Malta. Nelson formed a plan for attacking it while at anchor at Gozo; but on June 22nd intelligence reached him that the French had left that island on the 16th, the day after their arrival. It was clear that their destination was eastward—he thought for Egypt—and for Egypt, therefore, he made all sail. Had the frigates been with him he could scarcely have failed to gain information of the enemy: for want of them, he only spoke three vessels on the way; two came from Alexandria, one from the Archipelago; and neither of them had seen anything of the French. He arrived off Alexandria on the 28th, and the enemy were not there, neither was there any account of them; but the governor was endeavouring to put the city in a state of defence, having received advice from Leghorn that the French expedition was intended against Egypt, after it had taken Malta. Nelson then shaped his course to the northward, for Caramania, and steered from thence along the southern side of Candia, carrying a press of sail, both night and day, with a contrary wind.

Baffled in his pursuit, he returned to Sicily. The Neapolitan ministry had determined to give his squadron no assistance, being resolved to do nothing which could possibly endanger their peace with the French Directory; by means, however, of Lady Hamilton’s influence at court, he procured secret orders to the Sicilian governors; and, under those orders, obtained everything which he wanted at Syracuse—a timely supply, without which, he always said, he could not have recommenced his pursuit with any hope of success. “It is an old saying,” said he in his letter, “that the devil’s children have the devil’s luck. I cannot to this moment learn, beyond vague conjecture, where the French fleet are gone to; and having gone a round of six hundred leagues at this season of the year, with an expedition incredible, here I am, as ignorant of the situation of the enemy as I was twenty-seven days ago.”

On July 25th he sailed from Syracuse for the Morea. Anxious beyond measure, and irritated that the enemy should so long have eluded him, the tediousness of the nights made him impatient; and the officer of the watch was repeatedly called on to let him know the hour, and convince him, who measured time by his own eagerness, that it was not yet daybreak. The squadron made the gulf of Coron on the 28th. Trowbridge entered the port, and returned with the intelligence that the French had been seen about four weeks before steering to the south-east from Candia. Nelson then determined immediately to return to Alexandria; and the British fleet accordingly, with every sail set, stood once more for the coast of Egypt. On August 1st, about ten in the morning, they came in sight of Alexandria. The port had been vacant and solitary when they saw it last; it was now crowded with ships, and they perceived with exultation that the tri-colour flag was flying upon the walls. At four in the afternoon, Captain Hood in the Zealous made the signal for the enemy’s fleet. For many preceding days Nelson had hardly taken either sleep or food: he now ordered his dinner to be served, while preparations were making for battle, and when his officers rose from the table and went to their separate stations, he said to them: “Before this time to-morrow I shall have gained a peerage or Westminster Abbey.”

The French, steering direct for Candia, had made an angular passage for Alexandria; whereas Nelson, in pursuit of them, made straight for that place, and thus materially shortened the distance. The two fleets must actually have crossed on the night of June 22nd.

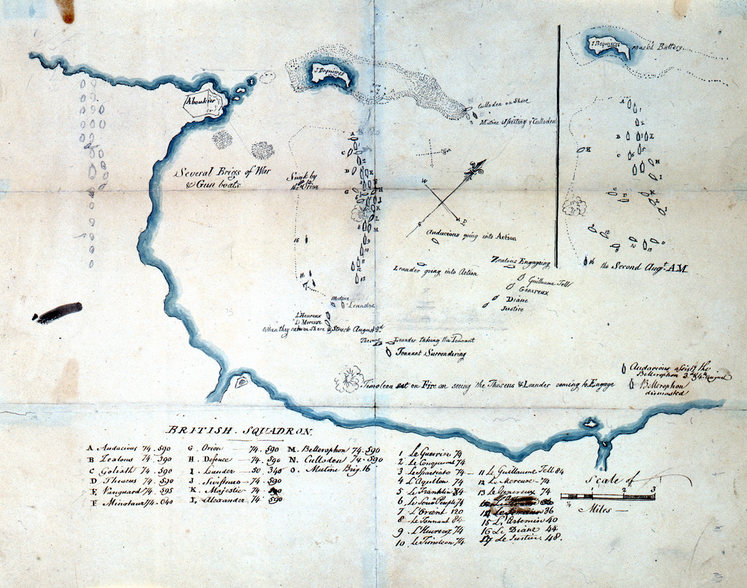

The French fleet arrived at Alexandria on July 1st; and Brueys, not being able to enter the port, which time and neglect had ruined, moored his ships in Aboukir Bay, in a strong and compact line of battle; the headmost vessel, according to his own account, being as close as possible to a shoal on the north-west, and the rest of the fleet forming a kind of curve along the line of deep water, so as not to be turned by any means in the south-west.

The advantage of numbers, both in ships, guns, and men, was in favour of the French. They had thirteen ships of the line and four frigates, carrying 1196 guns, and 11,230 men. The English had the same number of ships of the line, and one fifty-gun ship, carrying 1012 guns and 8068 men. The English ships were all seventy-fours: the French had three eighty-gun ships and one three-decker of one hundred and twenty.

During the whole pursuit it had been Nelson’s practice, whenever circumstances would permit, to have his captains on board the Vanguard, and explain to them his own ideas of the different and best modes of attack, and such plans as he proposed to execute, on falling in with the enemy, whatever their situation might be. There is no possible position, it is said, which he did not take into calculation. His officers were thus fully acquainted with his principles of tactics; and such was his confidence in their abilities, that the only thing determined upon, in case they should find the French at anchor, was for the ships to form as most convenient for their mutual support, and to anchor by the stern. “First gain the victory,” he said, “and then make the best use of it you can.” The moment he perceived the position of the French, that intuitive genius with which Nelson was endowed displayed itself; and it instantly struck him that where there was room for an enemy’s ship to swing there was room for one of ours to anchor. The plan which he intended to pursue, therefore, was to keep entirely on the outer side of the French line, and station his ships, as far as he was able, one on the outer bow and another on the outer quarter, of each of the enemy’s. This plan of doubling on the enemy’s ships was projected by Lord Hood, when he designed to attack the French fleet at their anchorage in Gourjean road. Lord Hood found it impossible to make the attempt; but the thought was not lost upon Nelson, who acknowledged himself on this occasion indebted for it to his old and excellent commander. Captain Berry, when he comprehended the scope of the design, exclaimed with transport, “If we succeed, what will the world say!”

“There is no if in the case,” replied the admiral; “that we shall succeed is certain: who may live to tell the story is a very different question.”

As the squadron advanced they were assailed by a shower of shot and shells from the batteries on the island, and the enemy opened a steady fire from the starboard side of their whole line, within half gun-shot distance, full into the bows of our van ships. It was received in silence: the men on board every ship were employed aloft in furling sails, and below in tending the braces and making ready for anchoring. A miserable sight for the French, who, with all their skill, and all their courage, and all their advantages of numbers and situation, were upon that element, on which, when the hour of trial comes, a Frenchman has no hope.

A French brig was instructed to decoy the English, by manœuvring so as to tempt them toward a shoal lying off the island of Bekier; but Nelson either knew the danger or suspected some deceit, and the lure was unsuccessful. Captain Foley led the way in the Goliath, outsailing the Zealous, which for some minutes disputed this post of honour with him. He had long conceived that if the enemy were moored in line of battle in with the land the best plan of attack would be to lead between them and the shore, because the French guns on that side were not likely to be manned, nor even ready for action. Intending, therefore, to fix himself on the inner bow of the Guerrier, he kept as near the edge of the bank as the depth of water would admit; but his anchor hung, and having opened his fire, he drifted to the second ship, the Conquerant, before it was clear, then anchored by the stern, inside of her, and in ten minutes shot away her mast. Hood, in the Zealous, perceiving this, took the station which the Goliath intended to have occupied, and totally disabled the Guerrier in twelve minutes. The third ship which doubled the enemy’s van was the Orion, Sir J. Saumarez; she passed to windward of the Zealous, and opened her larboard guns as long as they bore on the Guerrier, then passing inside the Goliath, sank a frigate which annoyed her, hauled round toward the French line, and anchoring inside, between the fifth and sixth ships from the Guerrier, took her station on the larboard bow of the Franklin and the quarter of the Peuple Souverain, receiving and returning the fire of both. The sun was now nearly down. The Audacious, Captain Gould, pouring a heavy fire into the Guerrier and the Conquerant, fixed herself on the larboard bow of the latter; and when that ship struck, passed on to the Peuple Souverain. The Theseus, Captain Miller, followed, brought down the Guerrier’s remaining main and mizen masts, then anchored inside of the Spartiate, the third in the French line.

While these advanced ships doubled the French line the Vanguard was the first that anchored on the outer side of the enemy, within half pistol-shot of their third ship, the Spartiate. Nelson had six colours flying in different parts of his rigging, lest they should be shot away;—that they should be struck, no British admiral considers as a possibility. He veered half a cable, and instantly opened a tremendous fire; under cover of which the other four ships of his division, the Minotaur, Bellerophon, Defence, and Majestic, sailed on ahead of the admiral. In a few minutes every man stationed at the first six guns in the fore part of the Vanguard’s deck was killed or wounded—these guns were three times cleared. Captain Louis, in the Minotaur, anchored next ahead, and took off the fire of the Aquilon, the fourth in the enemy’s line. The Bellerophon, Captain Darby, passed ahead, and dropped her stern anchor on the starboard bow of the Orient, seventh in the line, Brueys’ own ship, of one hundred and twenty guns, whose difference of force was in proportion of more than seven to three, and whose weight of ball, from the lower deck alone, exceeded that from the whole broadside of the Bellerophon. Captain Peyton, in the Defence, took his station ahead of the Minotaur, and engaged the Franklin, the sixth in the line; by which judicious movement the British line remained unbroken. The Majestic, Captain Westcott, got entangled with the main rigging of one of the French ships astern of the Orient, and suffered dreadfully from that three-decker’s fire; but she swung clear, and closely engaging the Heureux, the ninth ship on the starboard bow, received also the fire of the Tonnant, which was the eighth in the line. The other four ships of the British squadron, having been detached previous to the discovery of the French, were at a considerable distance when the action began. It commenced at half-past six; about seven, night closed, and there was no other light than that from the fire of the contending fleets.

Trowbridge, in the Culloden, then foremost of the remaining ships, was two leagues astern. He came on sounding, as the others had done: as he advanced, the increasing darkness increased the difficulty of the navigation, and suddenly, after having found eleven fathoms water, before the lead could be hove again, he was fast aground; nor could all his own exertions, joined to those of the Leander and the Mutine brig, which came to his assistance, get him off in time to bear a part in the action. His ship, however, served as a beacon to the Alexander and Swiftsure, which would else, from the course which they were holding, have gone considerably farther on the reef, and must inevitably have been lost. These ships entered the bay, and took their stations, in the darkness, in a manner long spoken of with admiration by all who remembered it. Captain Hallowell, in the Swiftsure, as he was bearing down, fell in with what seemed to be a strange sail; Nelson had directed his ships to hoist four lights horizontally at the mizen peak, as soon as it became dark, and this vessel had no such distinction. Hallowell, however, with great judgment, ordered his men not to fire: if she was an enemy, he said, she was in too disabled a state to escape; but, from her sails being loose, and the way in which her head was, it was probable she might be an English ship. It was the Bellerophon, overpowered by the huge Orient: her lights had gone overboard, nearly two hundred of her crew were killed or wounded; all her masts and cables had been shot away; and she was drifting out of the line, towards the lee side of the bay. Her station, at this important time, was occupied by the Swiftsure, which opened a steady fire on the quarter of the Franklin and the bows of the French admiral. At the same instant, Captain Ball, with the Alexander, passed under his stern, and anchored within side on his larboard quarter, raking him, and keeping up a severe fire of musketry upon his decks. The last ship which arrived to complete the destruction of the enemy was the Leander. Captain Thompson, finding that nothing could be done that night to get off the Culloden, advanced with the intention of anchoring athwart-hawse of the Orient. The Franklin was so near her ahead that there was not room for him to pass clear of the two; he, therefore, took his station athwart-hawse of the latter, in such a position as to rake both.

The two first ships of the French line had been dismasted within a quarter of an hour after the commencement of the action; and the others had in that time suffered so severely, that victory was already certain. The third, fourth, and fifth were taken possession of at half-past eight.

Meantime, Nelson received a severe wound on the head from a piece of langrage shot. Captain Berry caught him in his arms as he was falling. The great effusion of blood occasioned an apprehension that the wound was mortal. Nelson himself thought so: a large flap of the skin of the forehead, cut from the bone, had fallen over one eye, and the other being blind, he was in total darkness. When he was carried down, the surgeon—in the midst of a scene scarcely to be conceived by those who have never seen a cock-pit in time of action, and the heroism which is displayed amid its horrors,—with a natural and pardonable eagerness quitted the poor fellow then under his hands, that he might instantly attend the admiral. “No!” said Nelson, “I will take my turn with my brave fellows.” Nor would he suffer his own wound to be examined till every man who had been previously wounded was properly attended to. Fully believing that the wound was mortal, and that he was about to die, as he had ever desired, in battle and in victory, he called the chaplain, and desired him to deliver what he supposed to be his dying remembrance to Lady Nelson: he then sent for Captain Louis on board from the Minotaur, that he might thank him personally for the great assistance which he had rendered to the Vanguard; and, ever mindful of those who deserved to be his friends, appointed Captain Hardy from the brig to the command of his own ship, Captain Berry having to go home with the news of the victory. When the surgeon came in due time to examine his wound (for it was in vain to entreat him to let it be examined sooner) the most anxious silence prevailed; and the joy of the wounded men, and of the whole crew, when they heard that the hurt was merely superficial, gave Nelson deeper pleasure than the unexpected assurance that his life was in no danger. The surgeon requested, and as far as he could, ordered him to remain quiet; but Nelson could not rest. He called for his secretary, Mr. Campbell, to write the despatches. Campbell had himself been wounded, and was so affected at the blind and suffering state of the admiral, that he was unable to write. The chaplain was then sent for; but, before he came, Nelson, with his characteristic eagerness, took the pen, and contrived to trace a few words, marking his devout sense of the success which had already been obtained. He was now left alone; when suddenly a cry was heard on the deck that the Orient was on fire. In the confusion, he found his way up, unassisted and unnoticed; and, to the astonishment of every one, appeared on the quarter-deck, where he immediately gave orders that boats should be sent to the relief of the enemy.

It was soon after nine that the fire on board the Orient broke out. Brueys was dead: he had received three wounds, yet he would not leave his post; a fourth cut him almost in two. He desired not to be carried below, but to be left to die upon deck. The flames soon mastered his ship. Her sides had just been painted, and the oil-jars and paint-buckets were lying on the poop. By the prodigious light of this conflagration the situation of the two fleets could now be perceived, the colours of both being clearly distinguishable. About ten o’clock the ship blew up, with a shock which was felt to the very bottom of every vessel. Many of her officers and men jumped overboard, some clinging to the spars and pieces of wreck, with which the sea was strewn, others swimming to escape from the destruction which they momentarily dreaded. Some were picked up by our boats; and some even in the heat and fury of the action were dragged into the lower ports of the nearest British vessel by the British sailors. The greater part of her crew, however, stood the danger till the last, and continued to fire from the lower deck. This tremendous explosion was followed by a silence not less awful: the firing immediately ceased on both sides, and the first sound which broke the silence was the dash of her shattered masts and yards falling into the water from the vast height to which they had been exploded. It is upon record that a battle between two armies was once broken off by an earthquake:—such an event would be felt like a miracle; but no incident in war, produced by human means, has ever equalled the sublimity of this co-instantaneous pause, and all its circumstances.

About seventy of the Orient’s crew were saved by the English boats. Among the many hundreds who perished, were the commodore, Casa-Bianca, and his son, a brave boy, only ten years old. They were seen floating on a shattered mast when the ship blew up. She had money on board (the plunder of Malta) to the amount of £600,000 sterling. The masses of burning wreck, which were scattered by the explosion, excited for some moments apprehensions in the English which they had never felt from any other danger. Two large pieces fell into the main and fore tops of the Swiftsure, without injuring any person. A port fire also fell into the main-royal of the Alexander: the fire which it occasioned was speedily extinguished. Captain Ball had provided, as far as human foresight could provide, against any such danger. All the shrouds and sails of his ship, not absolutely necessary for its immediate management, were thoroughly wetted, and so rolled up that they were as hard and as little inflammable as so many solid cylinders.

The firing recommenced with the ships to leeward of the centre, and continued till about three. At daybreak, the Guillaume Tell and the Genereux, the two rear ships of the enemy, were the only French ships of the line which had their colours flying; they cut their cables in the forenoon, not having been engaged, and stood out to sea, and two frigates with them. The Zealous pursued; but as there was no other ship in a condition to support Captain Hood, he was recalled. It was generally believed by the officers that if Nelson had not been wounded, not one of these ships could have escaped: the four certainly could not, if the Culloden had got into action, and if the frigates belonging to the squadron had been present, not one of the enemy’s fleet would have left Aboukir Bay. These four vessels, however, were all that escaped; and the victory was the most complete and glorious in the annals of naval history. “Victory,” said Nelson, “is not a name strong enough for such a scene;” he called it a conquest. Of thirteen sail of the line, nine were taken and two burnt; of the four frigates, one was sunk, another, the Artimese, was burnt by her captain, who, having fired a broadside at the Theseus, struck his colours, then set fire to his ship and escaped with most of his crew to shore. The British loss in killed and wounded amounted to 895. Westcott was the only captain who fell; 3105 of the French, including the wounded, were sent on shore, and 5225 perished.

The shore, for an extent of four leagues, was covered with wreck; and the Arabs found employment for many days in burning on the beach the fragments which were cast up, for the sake of the iron. Part of the Orient’s main mast was picked up by the Swiftsure. Captain Hallowell ordered his carpenter to make a coffin of it; the iron as well as wood was taken from the wreck of the same ship. It was finished as well and handsomely as the workman’s skill and materials would permit, and Hallowell then sent it to the admiral with the following letter,—”Sir, I have taken the liberty of presenting you a coffin made from the main mast of L’Orient, that when you have finished your military career in this world you may be buried in one of your trophies. But that that period may be far distant, is the earnest wish of your sincere friend, Benjamin Hallowell.”—An offering so strange, and yet so suited to the occasion, was received by Nelson in the spirit with which it was sent. As if he felt it good for him, now that he was at the summit of his wishes, to have death before his eyes, he ordered the coffin to be placed upright in his cabin.

Nelson was now at the summit of glory: congratulations, rewards, and honours were showered upon him by all the states, and princes, and powers to whom his victory gave a respite. At home he was created Baron Nelson of the Nile and of Burnham Thorpe, with a pension of £2000 for his own life, and those of his two immediate successors. A grant of £10,000 was voted to Nelson by the East India Company; the Turkish Company presented him with a piece of plate; the city of London presented a sword to him and to each of his captains; gold medals were distributed to the captains; and the first lieutenants of all the ships were promoted, as had been done after Lord Howe’s victory.

After the battle of the Nile, Nelson returned to Naples, where he renewed his friendship with Sir William and Lady Hamilton. Italy received him everywhere with open arms, and the most flattering welcome was given him by both court and people. The story of his stay in Italy, however, is the saddest chapter in his life, for it was here that his domestic happiness was destroyed, and his fine chivalrous nature received its only stain.

His birthday, which occurred a week after his arrival, was celebrated with one of the most splendid fêtes ever beheld at Naples. But, notwithstanding the splendour with which he was encircled, and the flattering honours with which all ranks welcomed him, Nelson was fully sensible of the depravity, as well as weakness, of those by whom he was surrounded. “What precious moments,” said he, “the courts of Naples and Vienna are losing! Three months would liberate Italy! but this court is so enervated, that the happy moment will be lost. I am very unwell; and their miserable conduct is not likely to cool my irritable temper. It is a country of fiddlers and poets, libertines and scoundrels.”

He saved the court from the inevitable consequences of misrule for a time, drove the French out of Rome, laid siege to Malta, and worked miracles of energy and skill in many ways, but he left Italy with the feeling that there was no pleasure in life.

Nelson was welcomed in England with every mark of popular honour. At Yarmouth, where he landed, every ship in the harbour hoisted her colours. The mayor and corporation waited upon him with the freedom of the town, and accompanied him in procession to church, with all the naval officers on shore and the principal inhabitants. Bonfires and illuminations concluded the day; and, on the morrow, the volunteer cavalry drew up and saluted him as he departed, and followed the carriage to the borders of the county. At Ipswich the people came out to meet him, drew him a mile into the town and three miles out. In London, he was feasted by the city, drawn by the populace from Ludgate Hill to Guildhall, and received the thanks of the common council for his great victory and a golden hilted sword studded with diamonds. Nelson had every earthly blessing except domestic happiness; he had forfeited that for ever.