Editor’s note: The following is extracted from The Story of the Great War: History of the European War from Official Sources (published 1916).

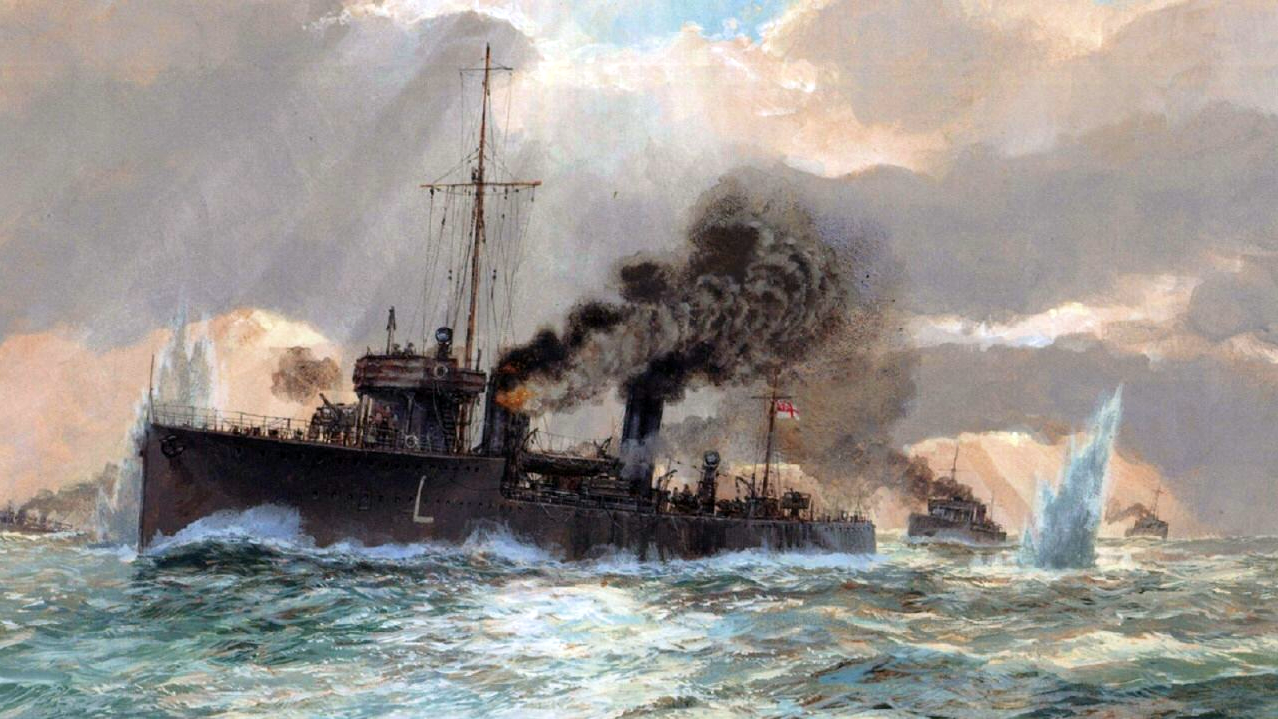

The Germans had taken heed of the value of mines from lessons learned at the cost of Russia in the war with Japan, and set about distributing these engines of destruction throughout the North Sea. The British admiralty knowing this, sent out a fleet of destroyers to scour home waters in search of German mine layers.

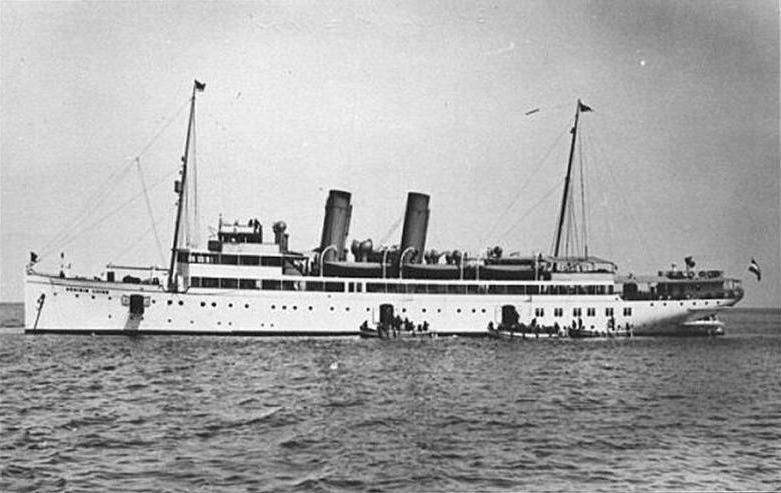

About ten o’clock on the morning of August 5, 1914, Captain Fox, on board the Amphion, came up with a fishing boat which reported that it had seen a boat “throwing things overboard” along the east coast. A flotilla, consisting of the Lance, Laurel, Lark and Linnet, set out in search of the stranger and soon found her. She was the Königin Luise, and the things she was casting overboard were mines. The Lance fired a shot across her bow to stop her, but she put on extra speed and made an attempt to escape. A chase followed; the gunners on the British ship now fired to hit. The first of these shots carried away the bridge of the German ship, a second shot missed, and a third and fourth hit her hull. Six minutes after the firing of the first shot her stern was shot away, and she went to the bottom, bow up. Fifty of her 130 men were picked up and brought to the English shore.

The first naval blood of the Great War had been drawn by Britain on August 5, 1914. The Königin Luise’s efforts had not been in vain. She had posthumous revenge on the morning of August 6, when the Amphion, flagship of the third flotilla of destroyers, hit one of the mines which the German ship had sowed. It was seen immediately by her officers that she must sink; three minutes after her crew had left her there came a second explosion, which, throwing débris aloft, brought about the death of many of the British sailors in the small boats, as well as that of a German prisoner from the Königin Luise.

All the world, with possibly the exception of the men in the German admiralty, now looked for a great decisive battle “between the giants” in the North Sea. The British spoke of it as a coming second Trafalgar, but it was not to take place. For reasons of their own the Germans kept their larger and heavier ships within the protection of Helgoland and the Kiel Canal, but their ships of smaller type immediately became active and left German shores to do what damage they might to the British navy. It was hoped, perhaps, that the naval forces of the two powers could be equalized and a battle fought on even terms after the Germans had cut down British advantage by a policy of attrition.

A flotilla of German submarines on August 9 attacked a cruiser belonging to the main British fleet, but was unable to inflict any damage. The lord mayor of the city of Birmingham received the following telegram the next morning: “Birmingham will be proud to learn that the first German submarine destroyed in the war was sunk by H. M. S. Birmingham.” Two shots from the British ship had struck the German U-15, and she sank immediately.

The German admiralty, even before England had declared war, suspected that the greatest use for the German navy in the months to come would be to fight the British navy, but they ventured to show their naval strength against Russia beforehand. Early in August they sent the Augsburg into the Baltic Sea to bombard the Russian port of Libau, but after doing a good bit of damage the German ship retired. It is probable that this raid was nothing more than a feint to remind Russia that she continually faced the danger of invasion from German troops landed on the Baltic shores under the cover of German ships, and that she must consequently keep a large force on her northern shores instead of sending it west to meet the German army on the border.

Among the German ships which were separated from the main fleet in the North Sea, and which were left without direct communication with the German admiralty after the cutting of the cables off the Azores by the Drake, were the cruisers Goeben and Breslau. When England declared war these two German ships were off the coast of Algeria. Both were very fast vessels, having a speed of 28 knots, and they were designed to go 6,000 knots without needing replenishment of their coal bunkers.

On the morning of August 5, after having bombarded some of the coast cities of Algeria they found themselves cut off on the east by a French fleet and on the west by an English fleet, but by a very clever bit of stratagem they escaped. The band of the Goeben was placed on a raft and ordered on a given moment to play the German national airs after an appreciable period. Meanwhile, under the cover of the night’s darkness the two German ships steamed away. After they had a good start the band on the raft began to play. The British patrols heard the airs and immediately all British ships were searching for the source of the music. To find a small raft in mid-sea was an impossible task, and while the enemy was engaged in it the two Germans headed for Messina, then a neutral port, which they reached successfully. The Italian authorities permitted them to remain there only twenty-four hours.

Before leaving they took a dramatic farewell, which received publicity in the press of the whole world, and which was designed to lead the British fleet commanders to believe that the Germans were coming out to do battle. Instead, they headed for Constantinople. They escaped all the ships of the British Mediterranean fleet with the exception of the cruiser Gloucester. With this ship they exchanged shots and were in turn slightly damaged, but they reached the Porte in seaworthy condition, and were immediately sold to the Turkish Government, which was then still neutral. The crews were sent to Germany and were warmly welcomed at Berlin. The officers responsible for their escape were disciplined by the British authorities.

Both Germany and England, the former by means of the eleven ships at large, and the latter by means of her preponderance in the number of ships, now made great efforts to capture trading ships of the enemy. When England declared war there was issued a royal proclamation which stated that up to midnight of August 14 England would permit German merchantmen in British harbors to sail for home ports, provided Germany gave British merchantmen the same privilege, but it was specified that ships of over 5,000 tons would not receive the privilege because they could be converted into fighting ships afterward. But on the high seas enemy ships come upon were captured.

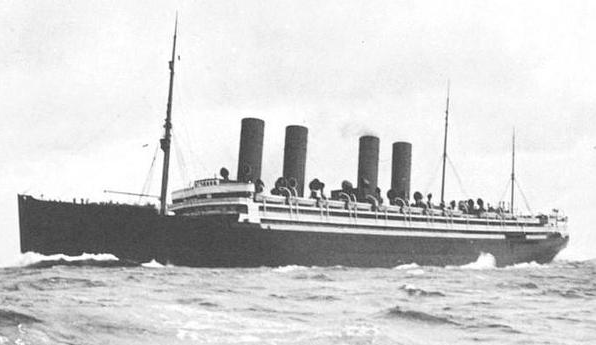

The German admiralty on August 1 had issued orders to German merchantmen to keep within neutral ports, and by this means such important ships as the Friedrich der Grosse and the Grosser Kurfürst eluded capture. In the harbor of New York was the Kronprinzessin Cecilie, a fast steamer of 23.5 knots. She left New York on July 28 carrying a cargo of $10,000,000 in gold, and was on the high seas when England declared war. Naturally she was regarded by the British as a great prize, and the whole world awaited from day to day the news of her capture, but her captain, showing great resourcefulness, after nearly reaching the British Isles, turned her prow westward, darkened all exterior lights, put canvas over the port holes and succeeded in reaching Bar Harbor, Me., on the morning of August 5.

Similarly the Lusitania and the French liner Lorraine, leaving New York on August 5, were able to elude the German cruiser Dresden, which was performing the difficult task of trying to intercept merchantmen belonging to the Allies as they sailed from America, while she was keeping watch against warships flying the enemies’ flags. Still more important was the sailing from New York of the German liner Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse. This ship had a speed of 22.5 knots and a displacement of 14,349 tons. During the first week of the war she cleared the port of New York with what was believed to be a trade cargo, but she so soon afterward began harassing British trading ships that it was believed that she left port equipped as a vessel of war or fitted out as one in some other neutral port. The continued story of the German raids on allied trading ships must form a separate part of this narrative. It was only a month after the outbreak of hostilities that the fleets of the allied powers had swept clean the seven seas of all ships flying German and Austrian flags which were engaged in trade and not in warlike pursuits.

The first naval battle of the Great War was fought on August 28, 1914. “A certain liveliness in the North Sea” was reported through the press by the British admiralty on the 19th of August. Many of the smaller vessels of the fleet of Admiral von Ingenohl, the German commander, such as destroyers, light cruisers, and scouting cruisers, were sighted. Shots between these and English vessels of the same types were exchanged at long range, but a pitched battle did not come for still a week. Meanwhile the British navy had been doing its best to destroy the mine fields established by the Germans. Trawlers were sent out in pairs, dragging between them large cables which cut the mines from the sea-bottom moorings: On being loosened they came to the surface and were destroyed by shots from the trawlers’ decks.

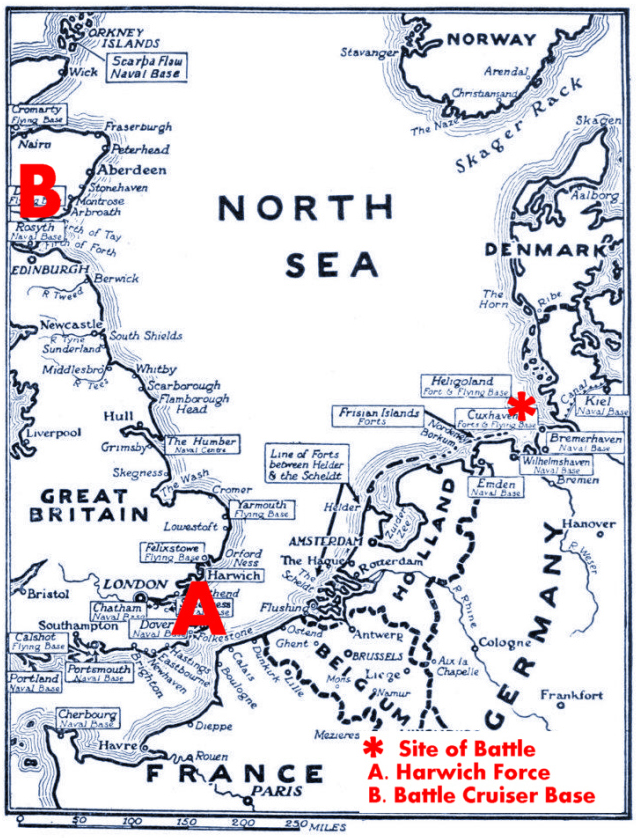

On the 28th of August came the battle off the Bight of Heligoland. The island of Heligoland had been a British possession from 1807 till 1890, when it was transferred to Germany by treaty. It was seen immediately by the Germans that it formed an excellent natural naval base, lying as it does, thirty-five miles northwest of Cuxhaven and forty-three miles north of Wilhelmshaven. They at once began to augment the natural protection it afforded with their own devices. Two Zeppelin sheds were erected, concrete forts were built and 12-inch guns were installed. The scene of the battle which took place here was the Bight of Heligoland, which formed a channel eighteen miles wide some seven miles north of the island and near which lay the line of travel for ships leaving the ports of the Elbe.

British submarines which had been doing reconnaissance work on the German coast since August 24 reported to the British commander, Admiral Jellicoe, that a large force of German light cruisers and smaller craft were lying under the protection of the Heligoland guns, and he immediately arranged plans for leading this force away from that protection in order to give it battle. Briefly the plans made provided that three submarines were to proceed on the surface of the water to within sight of the German ships and when chased by the latter were to head westward. The light cruisers Arethusa and Fearless were detailed to run in behind any light German craft which were to follow the British submarines, endeavoring to cut them off from the German coast, and these two vessels were backed by a squadron of light cruisers held in readiness should the first two need assistance. Squadrons of cruisers and battle cruisers were detailed to stay in the rear, still further to the northwest, to engage any German ships of their own class which might get that far.

It was at midnight on August 26 that Commodore Keyes moved toward Heligoland with eight submarines accompanied by two destroyers. During the next day—August 27—this force did nothing more than keep watch for German submarines and scouting craft, and then took up its allotted position for the main action. The morning of the 28th broke misty and calm. Under half steam three of the British submarines, the E-6, E-7, and E-8 steamed toward the island fortress, showing their hulls above water and followed by the two detailed destroyers.

The mist thickened. Still more slowly and cautiously went the British submersibles, and while they went above water, five of their sister craft traveled under the surface. Here was the bait for the German ships under Heligoland’s guns. Would they bite?

The Germans soon gave the answer. First there crept out a German destroyer which took a good look at the situation and then gave wireless signals to some twenty more of her type, which soon came out to join her. The twenty-one little and speedy German boats bravely came out and chased the two British destroyers and three submarines, while a German seaplane slowly circled upward to see if the surrounding regions harbored enemies. Presumably the airman found what he sought for he soon flew back to report to Heligoland. The peaceful aspect of the waters to the east of the island immediately changed, as a squadron of light cruisers weighed anchor and put out after the retiring Britishers.

Before a description of the fighting can be given it is necessary to understand the plan of the fight as a whole. Assuming that the page on which these words are printed represents a map of the North Sea and that the points of the compass are as they would be on an ordinary chart, we have the island of Heligoland, half an inch long and a quarter of an inch wide, situated in the lower right-hand corner of this page, with about half an inch separating its eastern side from the right edge of the page and the same distance separating it from the bottom. The lower edge of the page may represent the adjoining coasts of Germany and Holland, and the right-hand edge may represent the coast of the German province of Schleswig and the coast of Denmark.

At seven o’clock on the morning of August 28 the positions of the fighting forces were as follows: The decoy British submarines were making a track from Heligoland to the northwest, pursued by a flotilla of German submarines, destroyers, and torpedo boats, and a fleet of light cruisers. On the west—the left edge of the page, halfway up—there were the British cruisers Arethusa and Fearless accompanied by flotillas, and steaming eastward at a rate that brought them to the rear of the German squadron of light cruisers, thus cutting off the latter from the fortress. In the southwest—the lower left-hand corner of the page—there was stationed a squadron of British cruisers, ready to close in when needed; in the northwest—the upper left-hand corner of the page—there were stationed a squadron of British light cruisers and another of battle cruisers, and it was toward these last two units that the decoys were leading the German fleets.

The Arethusa and Fearless felt the first shock of battle, on the side of the British. The German cruiser Ariadne closed with the former, while the latter soon found itself very busy with the German cruiser Strassburg. For thirty-five minutes—before the Fearless drew the fire of the Strassburg—the two German vessels poured a telling fire into the Arethusa, and the latter was soon in bad condition, but she managed to hold out till succored by the Fearless, and then planted a shell against the Ariadne which carried away her forebridge and killed her captain. The scouting which had been done by the smaller craft of the German fleets showed their commanders that there were other British ships in the neighborhood besides the two they had first engaged, and it was thought wiser to withdraw in face of possible reenforcement of the British, consequently the Strassburg and Ariadne turned eastward to seek the protection of the fortress. The Arethusa, a boat that had been in commission but a week when the battle was fought, was in a bad way; all but one of her guns were out of action, her water tank had been punctured and fire was raging on her main deck amidships. The Fearless passed her a cable at nine o’clock and towed her westward, away from the scene of action, while her crew made what repairs they could.

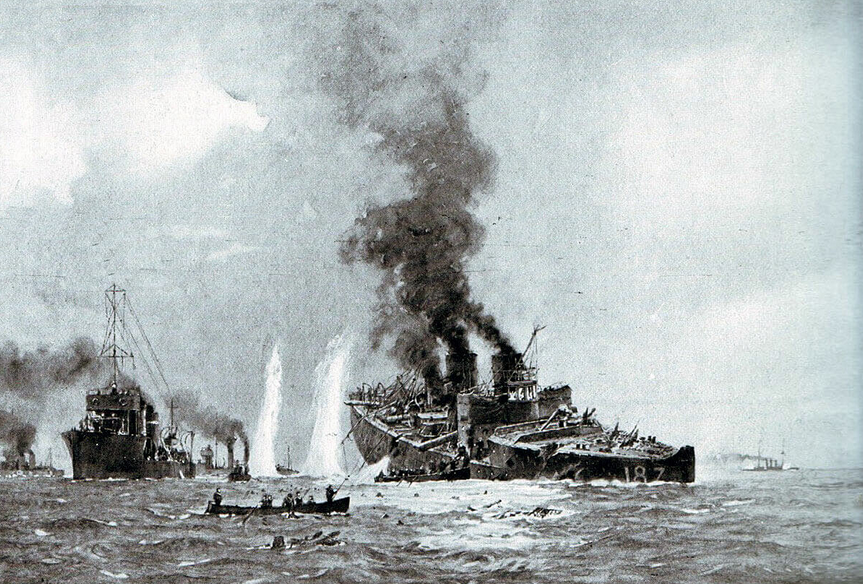

The flotillas of both sides had meanwhile been busy. At the head of the squadron of German destroyers that came out of the waters behind Heligoland was the V-187. Without slacking speed she steamed straight for the British destroyers, her small guns spitting rapidly, but she was outnumbered by British destroyers, which poured such an amount of steel into her thin sides that she went under, her guns firing till their muzzles touched the water and her crew cheering as they went to their deaths. A few managed to keep afloat on wreckage, and during a lull in the fighting, which lasted from nine o’clock till ten, boats were lowered from the British destroyers Goshawk and Defender to pick up these stranded German sailors.

The commanders of the German fleet, perceiving these small boats from afar, thought that the British were resorting to the old principle of boarding, and the German light cruiser Mainz came out to fire upon them. Two of the British small boats had to be abandoned as their mother ships made off before the oncoming German. They were in a perilous position, right beneath the guns of the fortress. But now a daring and unique rescue took place. The commander of the British submarine E-4 had been watching the fighting through the periscope of his craft, and seeing the helpless position of the two small boats, he submerged, made toward them, and then, to the great surprise of the men in them, came up right between them and took their occupants aboard his boat.

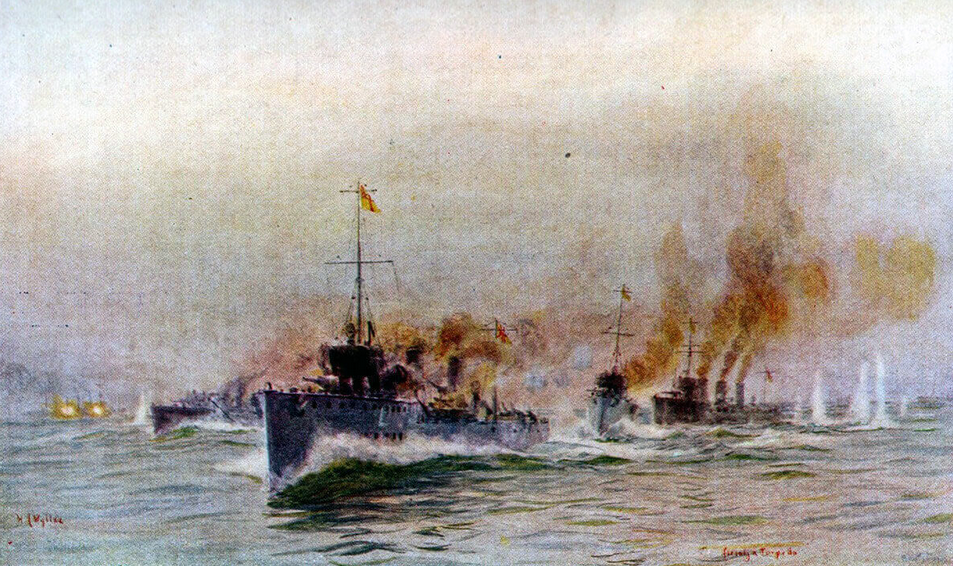

Repairs had been made on the Arethusa which enabled her to go into action again by ten o’clock. Accompanied again by two light cruisers of ten four-inch guns and the Fearless, she turned westward in answer to calls for assistance from the destroyers Lurcher and Firedrake, which accompanied the submarines and which reported that they were being chased by fast German cruisers. Suddenly the light cruiser Strassburg again came out of the mist and bore down on the British cruisers. Her larger guns were too heavy and had too long a range for those of the British craft, and the latter immediately sent out calls which brought into action for the first time certain ships belonging to the squadron of British light cruisers, which had been stationed to the northwest—the upper left-hand corner of the page.

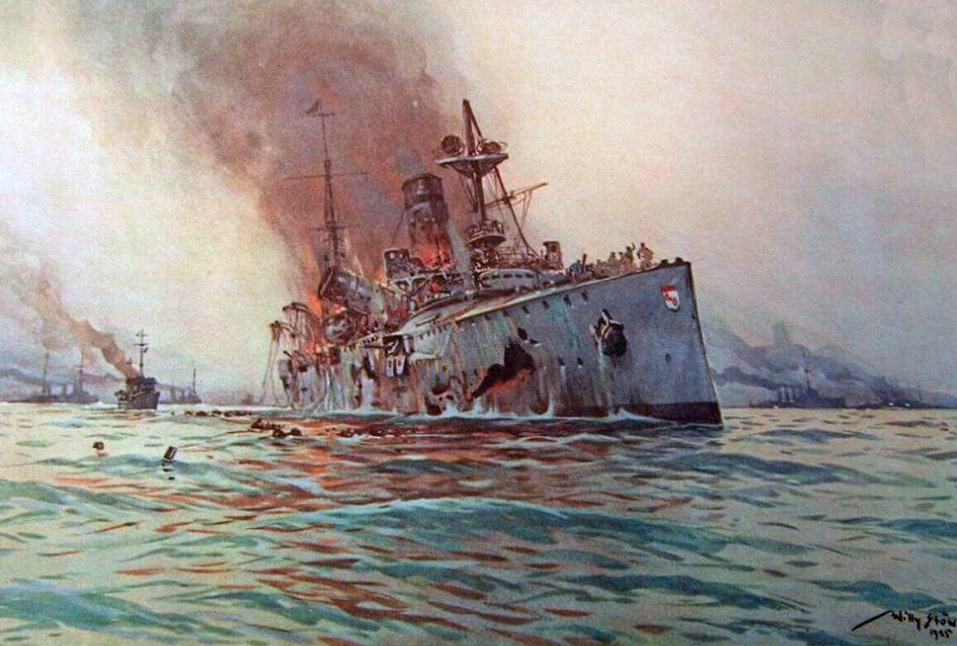

The vessels which answered the calls were the light cruisers Falmouth and Nottingham with eight eight-inch and nine six-inch guns respectively, but before arriving the Strassburg still had time to inflict more damage on the Arethusa. The cruisers Köln and Mainz joined the Strassburg, and the British vessels were having a bad time of it when their commander ordered the Fearless to concentrate all fire on the Strassburg. This, and a concentrated fire from the destroyers, proved too strong for her and she turned eastward, disappearing in the mist off Heligoland. The Mainz then received the attention of all available British guns, including the battle cruiser Lion, and soon fire broke out within her hold. Next her foremast, slowly tottering and then inclining more and more, crashed down upon her deck, a distorted mass. Following that came down one of her funnels. The fire which was raging aboard her was hampering her machinery, and her speed slackened; the moment to strike with a torpedo had come, and one of these “steel fishes” was sent against her hull below water. In the explosion which followed one of her boilers came out through her deck, ascended some fifty feet and dropped down near her bow; her engines stopped, and she began to settle slowly, her bow going down first.

It was now noon. From behind the veil of the surrounding mist came the Falmouth and Nottingham, which with the guns in their turrets completely finished the hapless Mainz, and their sailors openly admired the bravery of her crew, which, while she sank, maintained perfect order and sang the German national air.

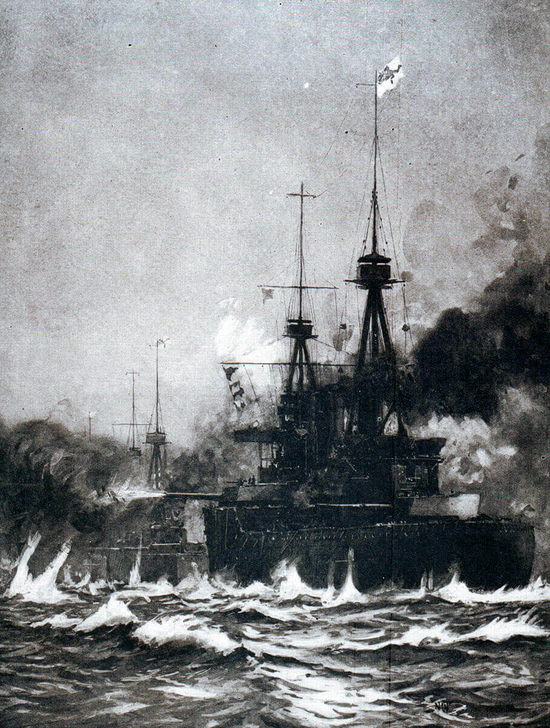

There was yet the Köln with which the Arethusa had to do battle. But by now the heavy British battle cruisers Lion and Queen Mary had also come down from the northwest to take part in the fighting, and letting the Arethusa escape from the range of the light cruiser Köln, they went for the German, which, overpowered, fled toward Heligoland. While the chase was on the Ariadne again made her appearance and came to the aid of the Köln, but the light cruiser Ariadne carried no gun as effective in destructive power as the 13.5-inch guns of the Lion, and she, too, had to seek safety in flight. The British ships then finished the Köln; so badly was she hit that when the British small boats sought the spot where she quickly sank they found not a man of her crew afloat. Every man of the 370 of her crew perished.

The afternoon came, and with its advent the mist, which had kept the guns of Helgoland’s forts out of action, had cleared off the calm waters of the North Sea. By the time the sun had set only floating wreckage gave evidence that here brave men had fought and died. By evening the respective forces were in their home ports, being treated for their hurts. The Germans had lost the Mainz, Köln, and Ariadne, and the Strassburg had limped home. The loss in destroyers and other small craft in addition to that of the V-187 was not known. The loss on the British side had not entailed that of a large ship, but the Arethusa when she returned to her home port was far from being in good condition, and some of the smaller boats were in the same circumstances.

Admiral von Ingenohl was committed more strongly than ever, as a result of this engagement, to the belief that the best policy for his command would be to keep his squadrons within the protection afforded by Heligoland and that the most damage could be done to the enemy by picking off her larger ships one by one. In other words, he again turned to the policy of attrition. He immediately put it into force.

On the 3d of September the British gunboat Speedy struck a mine in the North Sea and went down. It was only two days later that the light cruiser Pathfinder was made the true target of a torpedo fired by a German submarine off the British eastern coast, and she, too, went to the bottom. But the British immediately retaliated, for the submarine E-9 sighted the German light cruiser Hela weathering a bad storm on September 13 between Heligoland and the Frisian coast. A torpedo was launched and found its mark, and the Hela joined the Köln and Mainz. Up to this point the results of attrition were even, but the Germans scored heavily during the following week.

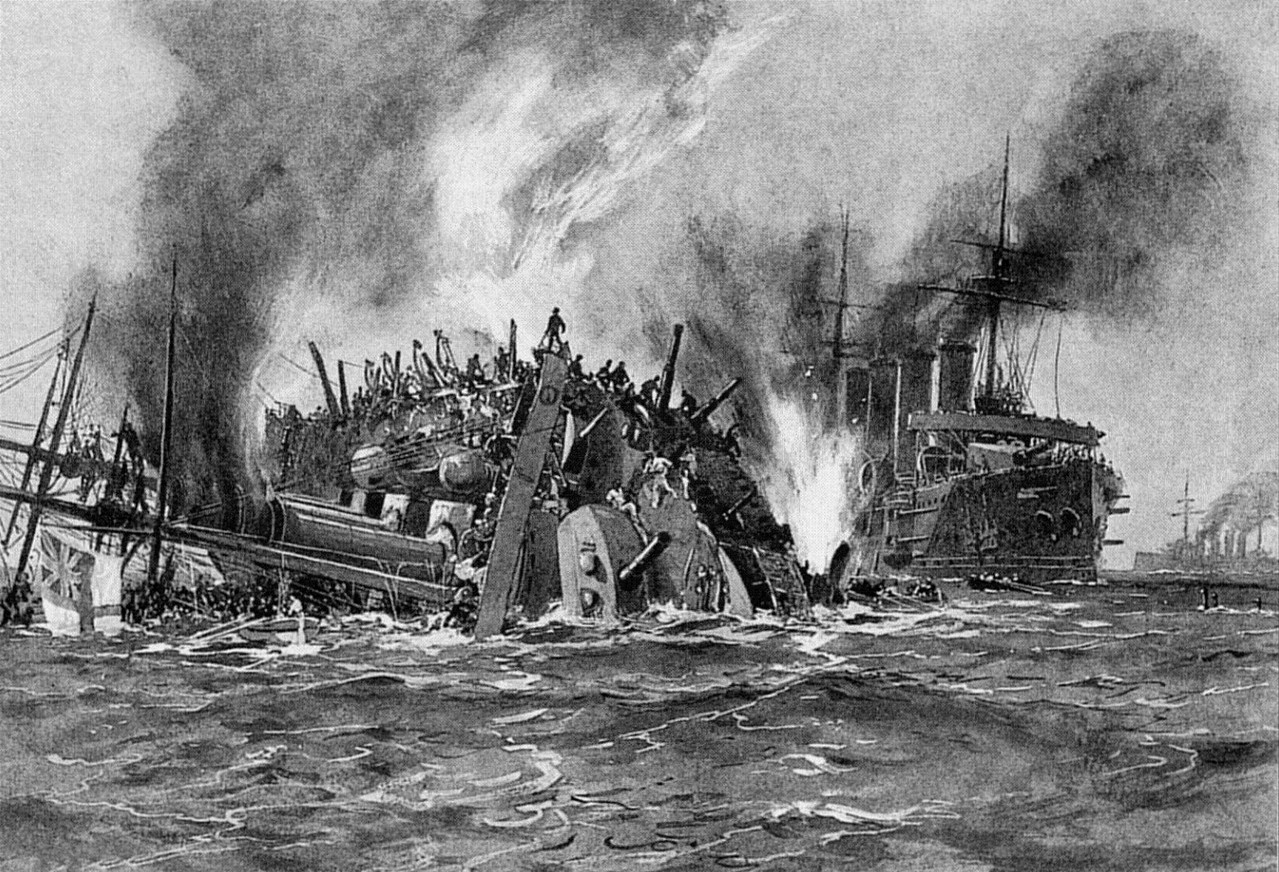

On September 22 the three slow British cruisers Cressy, Hogue, and Aboukir were patrolling the waters off the Dutch coast, unaccompanied by small craft of any kind, when suddenly, at half past six in the morning, the Aboukir crumpled and sank, the victim of another submarine attack. But the commander of the Hogue thought she had been sunk by hitting a mine, and innocently approached the spot of the disaster to rescue such of the crew of the Aboukir as were afloat. The work of mercy was never completed, for the Hogue itself was hit by two torpedoes in the next few moments, and she joined her sister ship. The commander of the Cressy, failing to take a lesson from what he had witnessed, now approached, and his ship was also hit by two torpedoes, making the third victim of the German policy of attrition within an hour, and Captain Lieutenant von Weddigen, commander of the U-9, which had done this work, immediately became a German hero.