Editor’s note: The following is extracted from The Heroic Record of the British Navy: A Short History of the Naval War 1914-1918, by Archibald Hurd and H.H. Bashford (published 1919).

Situated off the southeast coast of South America the group of islands, known as the Falklands, had definitely belonged to Great Britain since 1833. It consisted of about a hundred larger and smaller islands, the two chief being East and West Falkland, separated by a narrow channel of water known as the Falkland Sound. About 250 miles, at the nearest point, from Tierra del Fuego in the extreme south of the continent, they were some 300 miles distant from the Atlantic entrance of the Magellan Straits. Their climate was healthful but not attractive. Rain fell on more than half the days of the year. The seas surrounding them, even in their December midsummer, were of an arctic coldness and more often than not shrouded with mists that made navigation difficult and unpleasant. The chief industry was sheep farming, most of the farmers and shepherds being of Scottish descent; but there was a certain amount of business done at Port Stanley in the way of ship-repairing and the provision of marine stores.

Until 1904, when it was abandoned as such, Port Stanley had been a naval station, and it still remained the principal town of the islands and the headquarters of the Government. Situated on the easternmost projection of the eastern of the two chief islands, it had a population of about a thousand, and stood on a tongue of land between the ocean on the south and the innermost of two natural and connected harbours on the north. Of these, the outer and larger was known as Port William, with its entrance to the east, the inner recess, on the shore of which stands the town, being known as Port Stanley.

In 1914 the Governor was the Hon. W. L. Allardyce, and it was toward the middle of October that he heard from the Admiralty that a raid on the islands was to be expected and that suitable precautions should be taken. Accordingly, on October 19th, a notice was posted that all women and children were to leave Port Stanley; and this was promptly obeyed, camps being formed inland, and provisions stored in various places. All Government documents, books, and monies were removed from the town and conveyed to a safe hiding-place; while, at the same time, a defense force was organized under the Governor, mustering, all told, about 130 men. All were good shots, and, with their two machine-guns, were fully prepared to fight to the last. On advice from the Admiralty, they were to adopt retiring tactics, should the Germans land; horses and emergency rations were provided for everybody; and, with their knowledge of the terrain, and their island hardihood, there can be little doubt that they would have put up a strong resistance.

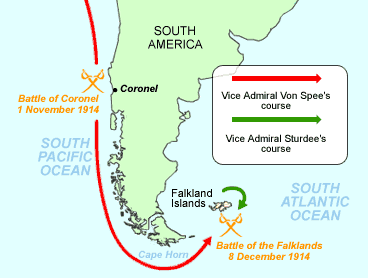

This was the position in the island when, on November 3d, a wireless message was received, announcing the disaster at Coronel; and, five days later, this was followed by the arrival of the Glasgow and Canopus. A raid by the enemy now amounted to a certainty; both the British vessels believed the Germans to be on their heels; and when, a few hours afterward, they received orders to sail for Monte Video, the feelings of the defenders naturally sank a little. They kept up a stout heart, however; the strictest watch was maintained; for several days and nights the Governor never had his clothes off; and, when the Canopus reappeared, having been turned back before reaching Monte Video, in order to help the islanders with her guns, there was a general conviction that they would be able to give von Spee a somewhat difficult problem to solve on his arrival.

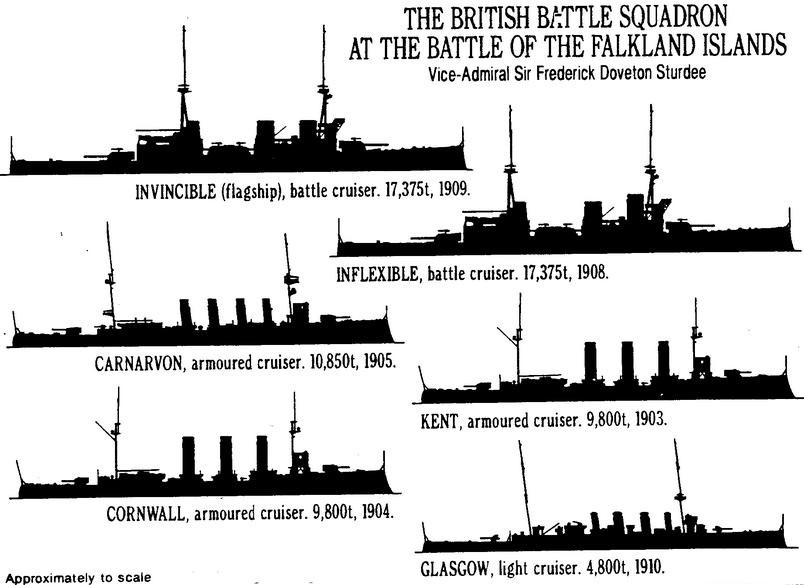

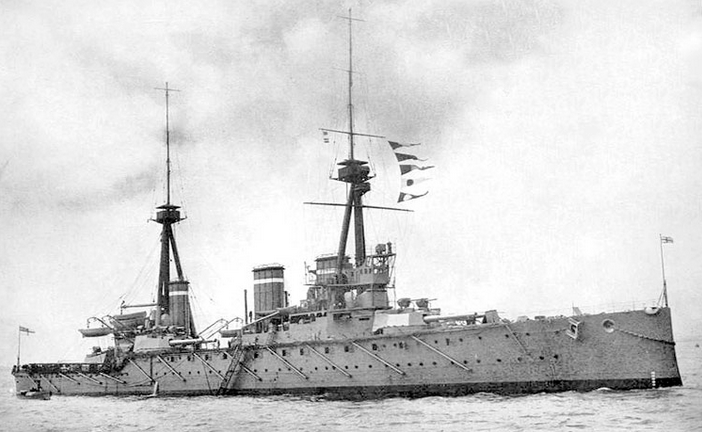

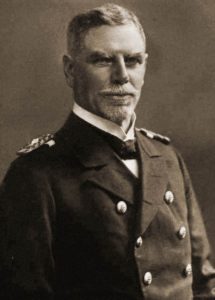

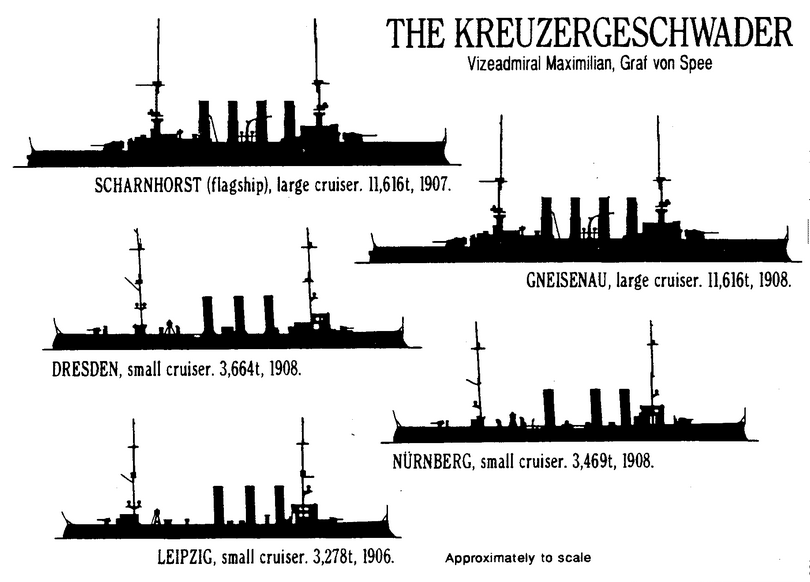

Laying a chain of mines at the entrance to Port William, the Canopus was put aground in the inner harbour, whence, protected by the land, she would be able to fire her big shells out to sea; her smaller guns were converted into batteries, mounted in strategic positions among the surrounding hills. Meanwhile in England, under Lord Fisher, who had been recalled to the Admiralty as First Sea Lord, secret and decisive measures had been instantly adopted. Within ten days of the Battle of Coronel, by an act of the same genius that had created them, the Invincible and Inflexible—two of our earlier, but still very powerful battle-cruisers, each capable of a speed of 27 knots and carrying eight 12-inch guns—had been detached from the Grand Fleet, coaled and munitioned, and, under Vice-Admiral Sir Doveton Sturdee, were steaming toward the equator, unknown to the world, to avenge Sir Christopher Cradock and his lost crew.

Ten days later, at a rendezvous in the South Atlantic, they met their assigned consorts under Rear-Admiral Stoddart; and here the fleet assembled that was to proceed, first to the Falkland Islands, and thence, round Cape Horn, to engage von Spee. Apart from its colliers, of which there were about fourteen, several of these being out-steamed on the way to Port Stanley, it consisted of the Carnarvon, with Rear-Admiral Stoddart, the Kent, Glasgow, Bristol, and the armed merchantman Macedonia, including, of course, the two battle-cruisers from England, Sir Doveton Sturdee flying his flag on the Invincible.

The Glasgow had been in Rio as recently as November 16th, but every precaution against discovery had been taken; all communication by wireless had been strictly forbidden by Admiral Sturdee; and, at about eleven o’clock on the morning of December 7th, the squadron slipped quietly into Port William. For the anxious defense force on the islands the long vigil was now at an end. For such of the officers as could be spared ashore, and for those whose vessels had to wait their turn for coaling it was a welcome opportunity to touch land again, and they were sufficiently prompt to make characteristic use of it. One of them tells us that, sallying out with his gun, he shot two geese and six hares for the wardroom larder—as ignorant as everybody else of the larger game that was even then heading for the islands.

For the most part, however, all on board every vessel were hard at work getting ready for the search—a search that was still believed, of course, to be inevitable, no news of von Spee having reached the island. The Glasgow and Bristol, in the inner harbour, were the first to coal, followed by the Carnarvon, who only finished at four o’clock the next morning, her collier, the Trelawney, then going to the Invincible. This was berthed beside her in the outer harbour of Port William, the Inflexible keeping them company, with the Kent and Cornwall lying a little to the south, the Kent, with her steam up, acting as guardship. Further to seaward, beyond the mine barrage, was anchored the Macedonia, serving as a look-out vessel; while in the inner harbour were the Bristol and Glasgow, with the old Canopus still aground there. So the night passed. At various points in the islands, the volunteer sentries kept their watch; and it was from one of these, stationed on Sapper’s Hill, above Port Stanley, that the first news of the approach of enemy vessels was received between seven and eight the next morning.

The day had dawned clear, with a calm sea and a light breeze blowing from the northwest. From horizon to horizon, in the glowing sunlight, the sea stretched blue as the Mediterranean. It was such a day as, in the Falkland Islands, might for weeks together have been prayed for in vain; and, hidden in the harbour, lay such a fleet as von Spee, in his most depressed moments, was unlikely to have pictured. That he would find the Canopus there he may have thought probable. That the Glasgow and Bristol might be there he had deduced from their wireless. But that the giant battle-cruisers, Invincible and Inflexible, lay quiet as death behind those painted hills—that this December morning was the last morning that he would ever look upon on earth—none had told him, and, for all his forebodings, he himself could never have guessed. But the stage was set again; the curtain had risen; the watcher on Sapper’s Hill had heralded the last act. Let us look down for a moment with impartial eyes upon the chosen scene. Far to the south, resolved at last on action, but soon to pay the price of its strange hesitation, steamed the German squadron with its two colliers, the Santa Isabel and the Baden. To the watcher on Sapper’s Hill, at that early hour, only the foremost cruisers were as yet observable, faint smudges on the southern horizon—the Gneisenau and the Nürnberg. Equally faint, but clear and at their mercy, must have seemed that spit of land to the observers on the Gneisenau, wholly unconscious, as they then were, of the brisk activities that lay behind it. Nor were the cruisers in the hidden harbour any more aware of what the day heralded for them. With the prospect before them of a voyage round Cape Horn, they were stirring with preparations, but not for immediate action. The Kent alone of them, acting as guard-ship at the mouth of Port William, had her steam up. Only the Glasgow and Bristol in the inner harbour had finished coaling and lay with full bunkers; and the latter had her fires out in order that her boilers might be cleaned. Beside the flagship Invincible, the colliers were still busy; the flag-lieutenant was yawning in his dressing-gown over a cup of tea. The Inflexible, on one side of her, was in similar case, while, upon the other, the Cornwall was busy repairing her engines. Over them all arched a sky of serene and cloudless beauty. The air was so limpid that, through powerful glasses, the events of fifteen miles away might be happening almost at hand.

The flag-lieutenant went on yawning. He had had a long day yesterday, had been working most of the night, and was short of sleep. There came a knock at the door. A signalman entered. The smudges on the horizon had revealed themselves as men-of-war. They could only be von Spee’s, and yet it was hardly believable. To tell the admiral was the work of an instant; and soon the amazing tidings were known throughout the fleet. The Kent was at once ordered to weigh anchor, and every ship in the squadron to raise steam for full speed. Colliers were shoved off. Sailors who were in their “land rig” scrambled out of it like quick-change artists. Down in the engine-rooms, grimed men worked miracles, of which, for the moment, let the Cornwall give an example. At eight o’clock, as we have said, she had her starboard engine down, with one cylinder opened for repairs at six hours’ notice; and yet, before ten o’clock, she was under way, and, by a quarter past eleven, making more than twenty knots.

Meanwhile, at twenty minutes past eight, the Sapper’s Hill signaller had reported more smoke on the horizon; and, a quarter of an hour later, as the Kent steamed to the harbour entrance, the captain of the Canopus reported this to be proceeding from two ships about twenty miles off, the two first sighted being now little more than eight miles away. Three minutes afterward yet another column of smoke was signalled from Sapper’s Hill; and the Macedonia was ordered to weigh anchor on the inner side of the other cruisers. It was now evident that von Spee was arriving in force, probably with the whole of his squadron; and, at twenty minutes past nine, the Gneisenau and Nürnberg were seen, broadside on, training their guns on the wireless station. By this time, however, at less than seven miles distance, they were well within range of the Canopus, who anticipated them by firing a salvo over the low-lying tongue of land that sheltered her. None of this first shower of 12-inch shells seems to have been effective in damaging the enemy; but it no doubt confirmed for the German admiral the presence of the Canopus in the harbour; and both the Gneisenau and Nürnberg were at once observed to alter their course. For a moment it appeared as if they intended to approach the Kent at the harbour entrance, but, a few minutes later, they wore away with the evident intention of joining their comrades.

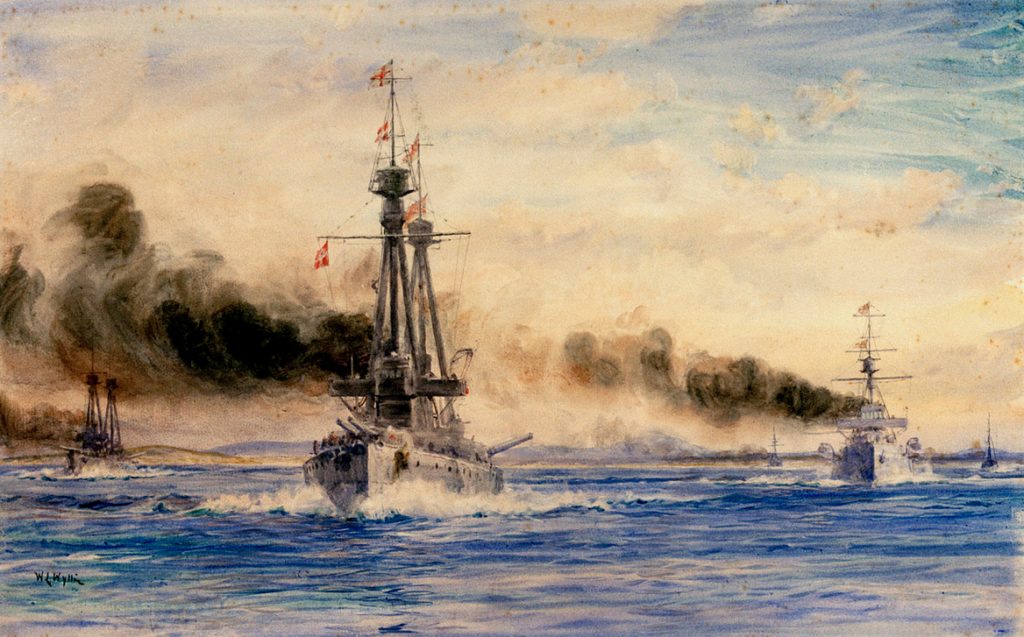

Both cruisers were now visible from the upper bridge of the Invincible; and the tops of the Invincible and Inflexible must have been equally apparent to them; though it still seems uncertain whether they had positively identified yet the two great cruisers that spelt their doom. Meanwhile, in the harbour, every preparation was being pushed forward with the utmost speed. At twenty minutes to ten the Glasgow weighed anchor and steamed down the harbour to join the Kent. Next to the two battle-cruisers, she was the speediest vessel in the squadron, and her orders were to observe the enemy. Five minutes later, the Carnarvon put out, followed by the Inflexible, Invincible, and Cornwall, the two big battle-cruisers burning their oil fuel, prudently spared for the occasion that had arrived.

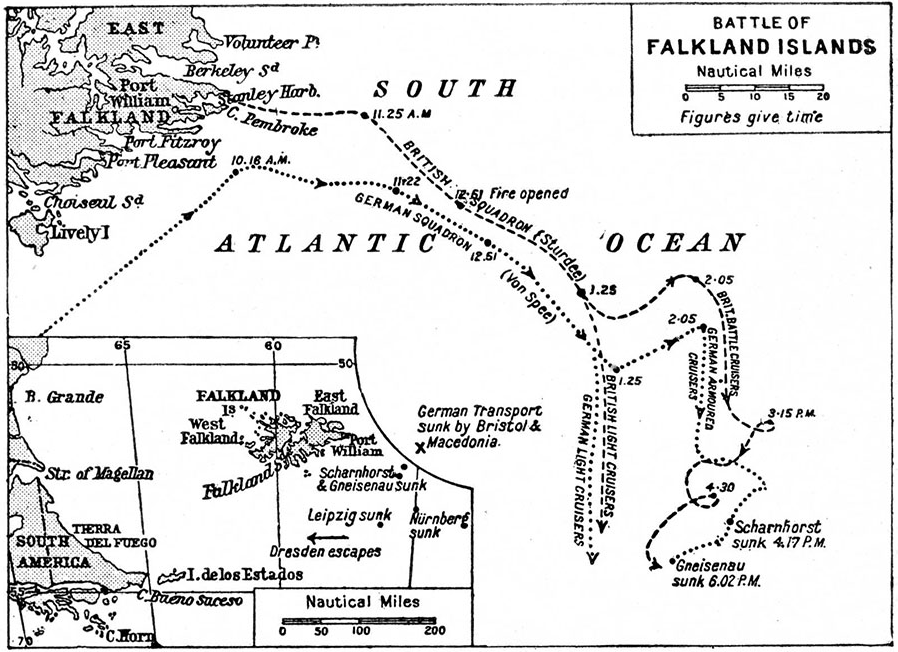

It was now twenty minutes past ten, and the character of the future action was already determined. For the Germans it had become instantly clear that their only hope—if such it might be called—lay in flight; and, on the British side, the order had been signalled for a general chase at full speed. Gathering pace, the two battle-cruisers from the north soon overtook and outstripped the Carnarvon and Kent, the position at eleven o’clock, with the squadron as a whole making about 20 knots, being as follows—the Glasgow was still leading, but had been ordered to remain within two miles of the flagship Invincible; next came the Invincible herself, with her decks flooded by hoses to prevent fire and wash away the last of the coal-dust; the Inflexible followed behind her, on her starboard quarter, with the Kent falling away from her astern and aport, followed by the Carnarvon, with the faster Cornwall reluctantly obeying orders to remain upon her quarter. Left behind in the harbour were the Bristol and Macedonia; but, just at this moment, on the other side of the island, a lady watcher at Fitz Roy, Mrs. Roy Felton, had seen and reported three other German vessels. Two of these—the third made its escape—were the colliers, already familiar to us, the Santa Isabel and Baden. The coal on board these vessels had been obtained from various sources since the action off Coronel, some from the Valentino, a French prize, and some from the British vessel Drummuir, captured on December 2d; and the Bristol and Macedonia were at once ordered by Admiral Sturdee to deal with them. Between nine and ten miles to the south, on a course east-north-east, von Spee in the Scharnhorst was travelling at full speed, followed by the Dresden, the Gneisenau, the Nürnberg, and the Leipzig, in the order named.

This was the situation then, and, before considering in detail one of the completest naval victories in our history, let us examine it for a moment as it presented itself to Admiral Sturdee, a remarkably cool-brained and deliberate tactician. With a long day in front of him, with nothing to fear in the way of destroyer or submarine-attack, with the whole of the enemy squadron now before his eyes, and with perfect visibility, he possessed under his command, in his own flagship, in the Inflexible, and in the Glasgow, three vessels at least that, in the matter of speed, were considerably superior to the enemy. Further, although the enemy’s gunnery was known to be excellent both in speed and accuracy, the 12-inch guns of the Invincible and Inflexible enabled him to dictate a long-range action; and there were two other weighty considerations that suggested the wisdom of such a course. For, while in gun-power the two battle-cruisers were far ahead of the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, in armour they were not so strong; and the nearest repairing yard was at Gibraltar. There were no obligations, therefore, to run any risk. There was every reason for not doing so. So long as, in the end, the Germans were sunk, a few hours would make no difference. Sailors fight best when well fed. Tobacco is an excellent solvent for undue excitement; and the British admiral therefore gave orders that dinner was to be served as usual, and that the men were to be allowed a few minutes for a quiet smoke. As one of the officers on the flagship afterward observed, they might almost have been at manoeuvres off Spithead—precisely the atmosphere that Admiral Sturdee had wisely designed to create.

It was at five minutes to one, at a range of about nine miles, that the first shot was fired by the Inflexible, taking for her target the light cruiser Leipzig, the last vessel of von Spee’s line. Five minutes afterward the Invincible followed suit, also taking the Leipzig for her target; and soon afterward the battle resolved itself into three separate encounters—that between the Invincible, Inflexible, and Carnarvon, and the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau; that between the Glasgow and Cornwall, and the Leipzig; and finally, after an epic chase, that in which the Kent overtook and sank the Nürnberg.

These conditions were first brought about when, at twenty minutes past one, the Leipzig turned away toward the southwest, soon to be followed by the Nürnberg and Dresden, with the Glasgow, Kent, and Cornwall in pursuit. With them had started the Carnarvon, but the rear-admiral in command of her, finding his speed insufficient to keep up with the light cruisers, had to give up the chase, and joined the Invincible and Inflexible in engaging the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. Leaving the action of the smaller cruisers in the capable hands of Captain Luce of the Glasgow, let us follow the fortunes of the other three in the most immediate and important task. Of these the ten-year-old Carnarvon, pushing on as stoutly as she could, was still trying vainly to keep up with her swifter sisters; and the first encounter was reduced, therefore, to a four-cornered fight lasting for about fifty minutes.

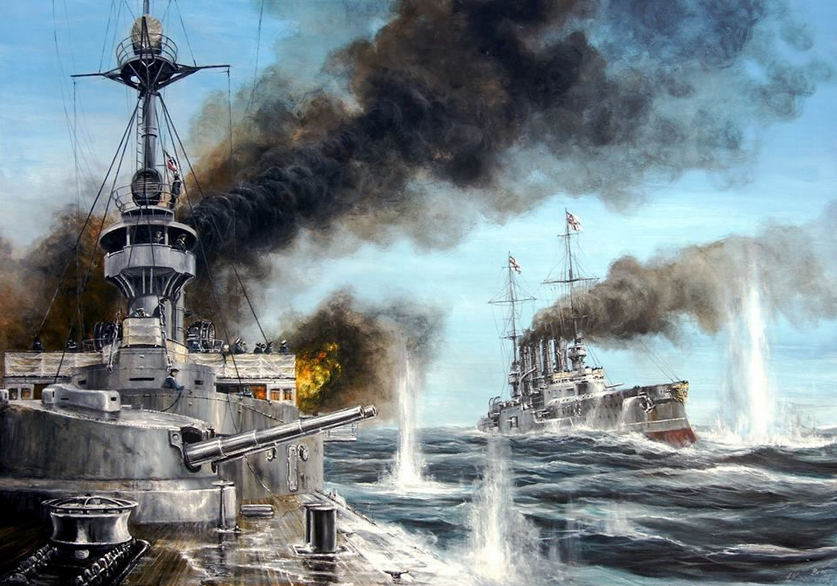

Beginning at twenty minutes past one, the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, after five minutes of a running battle, turned a little to port, began to close the range, and accepted the challenge; and, five minutes later, opened fire themselves. Though of smaller calibre, their guns, firing very rapidly, were as usual handled with extreme ability; and, in the words of the flag-lieutenant—half-way up the Invincible’s foremast, in the director-tower with Admiral Sturdee—they shot indeed “fiendishly well.” “We went on hammering away,” he wrote, “for some time, getting closer and closer, and they were hitting us pretty badly. I thought that our foremast had gone once. The Admiral and I were half-way up so as to get a good view. One of the legs of the mast was shot away. Shell fire is unpleasant, to put it mildly. Exploding shells, when they hit the ship, are worse, as one wonders how many she will stand. The Admiral was wonderfully cool and collected, and I bobbed my head at every shell, and got a stiff neck from doing it!”

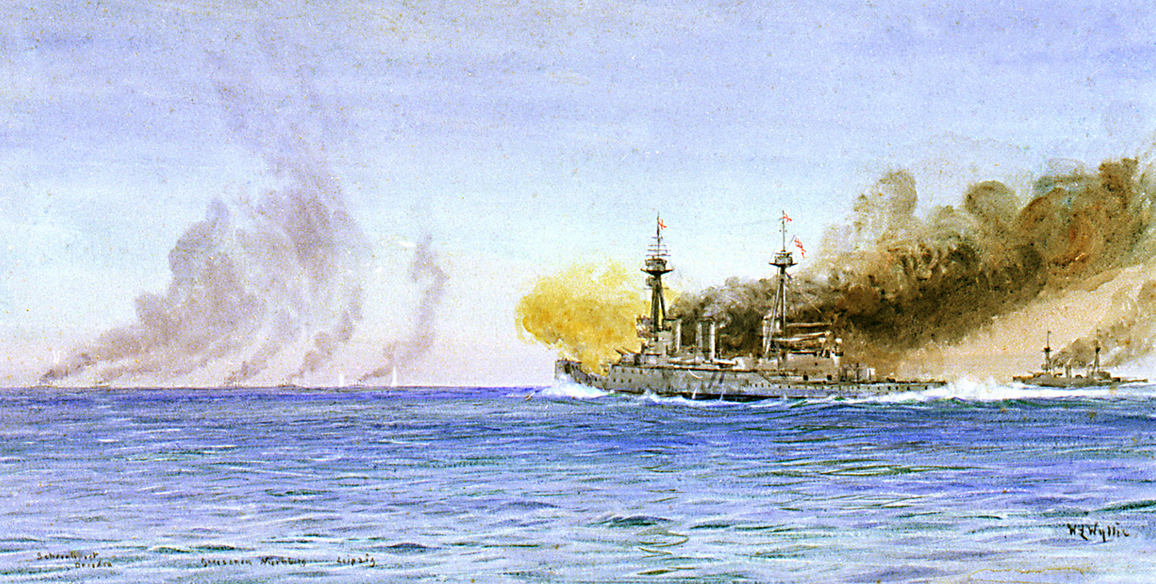

At a quarter to two the Invincible was being straddled—the Scharnhorst’s shells, that is to say, were exploding on both sides of her—and Admiral Sturdee, consistently with his plan of action, drew away a little to avoid undue risks. The Scharnhorst had by this time been hit on several occasions, but had not been disabled, though she broke off the action; and, at ten minutes past two, the fight became a chase again, the Invincible reopening fire at a quarter to three. For eight minutes, again out-ranging them, the Invincible and Inflexible hammered the two German cruisers, forcing them round to port once more to reply as best they could. The heavier British guns had now begun definitely to tell, however, and the Scharnhorst was already on fire forward. “We hit again and again,” wrote Midshipman John Esmonde in a letter to his father after the action. “First our left gun sent her big crane spinning over the side. Then our right gun blew her funnel to atoms, and then another shot from the left gun sent her bridge and part of the forecastle sky-high. We were not escaping free, however. Shots were hitting us repeatedly, and the spray from the splashes of their shells was hiding the Scharnhorst from us…. Down came the range—11,000, 10,000, 9,000, to 8,800. We were hitting the Scharnhorst very nearly every time. One beauty from our right gun got one of her turrets fair and square and sent it whistling over the side. Suddenly our right gun misfired—we had got a jamb and one gun was out of action. The breech had caught against one of the cages and would neither open nor shut. We opened up the trap hatch, and I jumped out, and down the ladder with two men to try and find a crowbar. The 12-inch guns were firing all round us, and our left gun was doing work for two now that the right was jammed. The German shells were whistling unpleasantly close and there were splinters flying all over the place. The Scharnhorst was firing heavily, but I could see she was in a bad way. She was down by the bows and badly on fire amidships. I got the crowbar and brought it in, but they wanted a hacksaw as well, so I jumped out again, and just as I was coming back I saw the Scharnhorst’s ensign dip (never knew whether it came down or not, because just then one of the lyddite shells hit her and there was a dense cloud of smoke all over her).[1] When it cleared she was on her side, and her propellers were lashing the water round into foam. Then she capsized altogether, going to the bottom.”

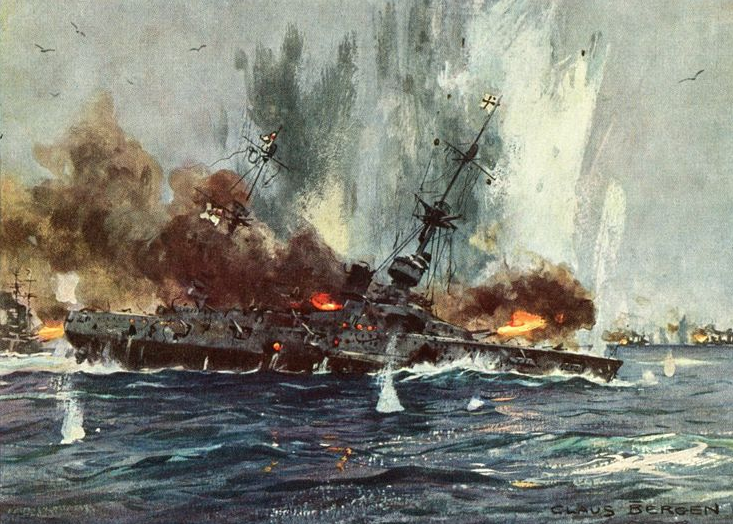

That was at a quarter past four; her consort the Gneisenau was still firing with all her guns; and, by this time, the old Carnarvon had at last arrived upon the scene—she had in fact fired a couple of shots at the Scharnhorst. The three cruisers, therefore, now turned their attention to the Gneisenau, who, after a moment’s hesitation, turned and stood at bay. Nothing in the whole day, indeed, was more gallant than her vain but desperate resistance. At half-past four she was still straddling the Invincible, though without causing casualties or serious damage. A few minutes after five, her forward funnel was knocked out and remained lolling against the second. Seven minutes later, just as she hit the Invincible for the last time, she was herself badly damaged again between the third and fourth funnels; and how accurate the British fire had become can be gathered from the notebook of one of her officers, afterward rescued. “Five ten,” he wrote, “hit, hit; 5.12, hit; 5:14, hit, hit, hit again; 5:20, after-turret gone; 5:40, hit, hit—on fire everywhere; 5:41, hit, hit—burning everywhere and sinking; 5:45, hit—men lying everywhere; 5:46, hit, hit.”

Listing heavily to starboard, and with her engines stopped, Admiral Sturdee had ordered the “Cease Fire” signal at about half-past five. But, before it could be hoisted, the Gneisenau began to shoot again, though now only spasmodically and with a single gun. She seems to have fired, indeed, until her ammunition was exhausted, when, at ten minutes to six, Admiral Sturdee ordered the “Cease Fire” again and, twelve minutes later, she turned on her side. “Then at last,” wrote another officer, “away first and second cutters, man sea-boat. For the Gneisenau is heeling right over on her side in the water. The beggars are done for. All our efforts will now be to save life, having done our utmost for five hours to destroy it…. Three of our boats are away picking up survivors. The Inflexible’s boats are doing the same, and so are the Carnarvon’s. The sea, which, so different from its state at noonday, is now quite angry, is strewn with floating wreckage supporting drowning men. To add to the misery, a drizzling rain is falling. We cast overboard every rope’s end we can, and try our hands at casting to some wretch feebly struggling within a few yards of the ship’s side. Missed him! Another shot. He’s farther off now! Ah! The rope isn’t long enough. No good, try someone else. He’s sunk now…. Many such do we see. Now we lend a hand hauling at a rope, pulling some poor devil out of the water. As they are hauled on deck they are taken below into the wardroom ante-room, or the Admiral’s spare cabin. Here with knives we tear off their dripping clothing. Then with towels we try to start a little warmth in their ice-cold bodies. They are trembling, violently trembling from the iciness of their immersion. Some of them had stuck it for thirty minutes in a temperature of 35 degrees Fahrenheit!”

“The Invincible alone,” reported Admiral Sturdee, “rescued 108 men, fourteen of whom were found to be dead after being brought on board. These men were buried at sea the following day with full military honours.” Few will say that they were undeserved.

By now the battle had been distributed over many leagues of sea; the units engaged were not only out of sight of each other, but even beyond the sound of each other’s guns; and it is time to return to Captain Luce in his war-scarred Glasgow, who, with the Kent and Cornwall, was pursuing the three light cruisers. More perhaps than to any others of the officers and crews engaged did their part in this struggle mean to those of the Glasgow. The sole survivors of Coronel, they had lived, as none of their comrades had done, for a bitter five weeks, with the picture of it before them. When all would fain have stayed and fought to the last, they had been compelled, in the interests of their service, to take the harder way. They had a peculiar debt to discharge, and now, if they could but seize it, their hour had come to repay it with interest.

It was at about twenty minutes past one when the three German cruisers had broken away toward the southwest, the Dresden leading with the Nürnberg and Leipzig following her on each quarter. The distance then separating them from the Glasgow, Kent, and Cornwall, was from nine to eleven miles; all were speedy, the Dresden being the fastest; and a long, stern chase therefore ensued. Of the three British cruisers, the Glasgow, in spite of her late experiences, was still considerably the swiftest; and she soon drew away from them, overhauling the Leipzig and Nürnberg, until at three o’clock she was within seven miles of the former. Her idea was now, if possible, so to outrange the Leipzig as to turn and delay her until the arrival of the Kent and Cornwall, far slower vessels even than the Leipzig, but carrying fourteen 6-inch guns to the Glasgow’s two. At three o’clock, therefore, she opened fire with her 6-inch guns, and, for more than an hour, engaged the Leipzig until the arrival of the Cornwall. By that time she had already hit her many times over, but had had to draw away on several occasions, owing to the accuracy of the Leipzig’s gunners. With time and speed and the range on his side, Captain Luce, like his admiral, could afford to be deliberate; and yet even so, with a little more luck, the Leipzig might have damaged the Glasgow rather severely. Two of her officers stationed in the control-top had a very narrow escape from losing their lives, a shell passing between them, and carrying away the hand of a signalman—three other men being wounded and one killed at about the same time. After an hour and a quarter, and having had an early tea, the Cornwall arrived on the scene, and was soon, as one of the Glasgow’s seamen, admitted, “shooting very well.”

We have last seen the Cornwall, not wholly to her liking, upon the quarter of the even slower Carnarvon; but, a little after noon, to her great satisfaction, she had received orders to go ahead. When the three light cruisers had broken to the south in their endeavour to escape, she had turned after them, as we have said, with her sister ship, the Kent, in the wake of the nimbler Glasgow. Now, thanks to the Glasgow and the superhuman efforts of their two engine-room staffs, both the Kent and Cornwall were at last in action, the former being ordered in pursuit of the Nürnberg—where we may leave her for a moment performing imperishable conjuring-tricks in the way of stoking and engine-driving, while her luckier consorts, already at close grips, were battering the Leipzig to pieces.

At twenty minutes to five, a shot from the Cornwall, at a range of between four and five miles, carried away her foremast; but, ten minutes later, after delivering a broadside, and as she was being hit herself, the Cornwall drew away a little. The Leipzig had now lost one of her funnels as well as being on fire aft, many of her guns being already silenced; but at six o’clock she was still firing well enough to hit the Cornwall severely and once more to force the latter away a little. This was only for a moment, however, the Cornwall reopening with lyddite shell at a quarter past six, and now pressing her attack home with tremendous force and accuracy to a range of less than three miles. In this the Glasgow joined her—it being obviously useless now to hunt for the Dresden miles away in the mist—and, by ten minutes to seven, the Leipzig was on fire everywhere, though her flag was still flying and her guns occasionally responding. The two British cruisers then stopped firing for a little, but dared not draw near for fear of a torpedo-attack. Blazing in every corner, with her sides red hot, and with great gaps in her torn by the lyddite, it seemed now that every moment must be the Leipzig’s last; but still she floated and would not strike her colours. Fire was again reopened, therefore, although, as one of the Cornwall’s officers said, “We all hated doing it,” and, half an hour later, she sent up a couple of rockets signifying that she surrendered and asking for help.

What her condition was then has been vividly described by Private Whittaker of the Royal Marine Light Infantry. “When we went right close,” he wrote to his mother, “she looked just like a night-watchman’s fire bucket, all holes and fire.” Searchlights were now playing upon her through the rain and darkness, but, in view of possible explosions, the boats could not approach too near; out of her crew of over three hundred, less than a score were saved; and, at just about nine o’clock, she rolled over to port, seemed to recover a moment, and then slipped out of sight.

So perished the Leipzig, not less gallantly, but as condignly as the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, news of whose destruction had been wirelessed to the Cornwall and Glasgow. Whatever might happen now, victory was assured; the Good Hope and Monmouth had been amply avenged; and to the Cornwall and Glasgow, buffeting home to Port Stanley, few happier moments were likely to come. Into the feelings of Captain Luce it would be impertinent to pry; but a little may be guessed, perhaps, from what follows. “About half an hour ago,” said one of his crew, writing home on December 11th, “the Captain made a speech, or rather tried to, but failed. He first of all read out the King’s message to the Fleet, and then tried to say a few words himself; ‘I have seen the Glasgow’s ship’s company fight twice, and I thank you for the way in which you fought. I couldn’t have a better ship’s company.’ Then he said, ‘I can’t say any more.'”

That is to leap forward, however, three days and to leave the Kent still ploughing after the Nürnberg—out of sight of everybody now and with the impossible task of making a doubtful 20-knot vessel catch one five knots faster; and not only overtake her, but bring her to action, with the weather changing and darkness not far off. But to the engine-room staff of the Kent and to her stokers no less than to Captain Allen—”Sink-her” Allen, they called him—the word impossible, for to-night at least, might not be whispered with impunity. There was the Nürnberg flushed from Coronel, and here was the Kent with her fourteen good guns; coal might be short and the engines in their second childhood, but if those guns did not find the Nürnberg, it would not be the fault of the engine-room. First out of harbour in the early morning, a spirit of extreme cheerfulness seems to have reigned in the Kent from the beginning of the action. Thus, at half-past ten, we find her officers drinking the toast of Deutschland unter Alles in sloe-gin. Soon afterward they lunched; and then—as many of them as could be spared—established themselves on the top of the forward gun-turret to watch the fun.

This was christened “the stalls” and seems to have been well patronized till half-past one when they went to Action Stations again. Falling out at twenty minutes past two, watch was resumed from the bridge, which then became known as “the upper circle.” At five minutes to four tea was served in the gun-room, and, twenty minutes later, Action Stations were taken up again. At that time the Leipzig and Nürnberg were well in view, with the Dresden almost out of sight on the horizon—the Leipzig on the starboard bow, nearer at hand, and being engaged by the Glasgow, and a moment afterward by the Cornwall, and the Nürnberg away to port and considerably more distant. Then came the order to pursue the latter, the Leipzig being given a salvo or two in passing; and it was then that there began the race that was destined to become traditional in every engine-room of the navy. With no coal to spare, everything combustible was crammed into her long-suffering furnaces. Tables and chairs, officers’ furniture, wooden companion-ladders, even planks from the deck, were knocked to pieces and thrust into the flames for the ultimate destruction of the Nürnberg.

“The entire staff,” afterward wrote one of her engineer officers, “was doing its best, and, my word it was a best. We pushed her along, more, more, more. The revolutions of the engines at the first time of starting were more than the revolutions the dockyard could get out of her, and she was worked up gently bit by bit, easying down occasionally when things looked as if they were not going quite right, or when they threatened to do so. An anxious moment was reached when we got on every ounce of steam that the engines could take. We were just then going some sixteen revolutions a minute faster than the Admiralty full power, and also the designed power of 22,000 horse-power, some 5,000 horse-power more than we ought to have done. In times of peace we should have been court-martialled for this, but we came out top…. We were doing from 2-½ to 3 knots faster than the old Kent had ever done before. We were doing over 25 knots ‘full speed,’ the highest ever attained being 22 knots.”

Fortunately for the Kent, too, the Nürnberg had her own boiler troubles, but they were of a different order, and she was unable to make her usual speed; and, after about an hour, the Kent was near enough to open fire at a range of a little over six miles. It was now the gunners’ opportunity, and though they were reservists, drawn, as one of the officers put it, “from all sorts of weird places,” they rose to the occasion, like first-class experts, and found their target almost at once. Nor could Captain Allen afford himself the license that had been the right policy for the other commanders. It was now past five; rain was falling; his supply of combustible bric-à-brac was strictly limited. It was a case of now or never, and the Kent, taking her punishment as it came, pushed the action for all she was worth.

With her foretop shot away down to the crows’ nest, and her silk ensign cut to ribbons; with her wireless knocked out, so that she could no longer send, though she was still able to receive, messages; with half a dozen holes through her funnels and several more in her side—she gained a quarter of a mile with every salvo until she was pounding the Nürnberg at less than three miles distance. Struck in all thirty-six times, and with five men killed and eleven wounded, the behaviour of all on board was, in their captain’s own words, “perfectly magnificent”—a typical example being that of Sergeant Mayes, whose courage and presence of mind probably saved the ship.

A bursting shell had started a fire among some cordite charges in the casemate. A tongue of flame had leaped down the hoist and into the ammunition passage, endangering the magazine. Without an instant’s pause, and although severely burned, Sergeant Mayes picked up a cordite charge and threw it away, afterward flooding the compartment and putting out a fire that had started in some neighbouring empty shell bags. No wonder that Captain Allen, writing afterward to the Association of Men at Kent, should have said that “though the enemy fought bravely to the very end, against such men as I have the honour to command, they never could have had a chance.”

By half-past six, the Nürnberg was on fire forward, all her guns being apparently silenced, and the Kent ceased shelling her, and drew up within two miles. Her flag was still flying, however, and the Kent opened fire again, but only for a few minutes longer, when the Nürnberg hauled her flag down and made signs of surrender. She was now blazing furiously, and listing heavily to starboard; and the Kent began to take measures to save life. Unfortunately all her boats had been holed by the Nürnberg’s fire, and, before she could launch them, they had to be repaired. Two were quickly patched up, but the crews were only successful in saving a dozen men, five of whom afterward died on board from the effects of wounds and exposure.

To complete the victory of this single-ship action everyone on board had contributed his utmost, but it seems probable that in history the larger share of the credit will be given unstintingly to the engineers and stokers. It was certainly bestowed on them by their comrades in the Kent. “The captain,” we are told, “nearly fell on the engineer-commander’s neck and kissed him when he ‘blew up’ after the action to see him and to advise as to the best speed to go back to harbour. He nearly shouted at him for some time: ‘My dear fellow, my dear engineer-commander! You won the action, you did it splendid! Without your speed we should have lost everything.'”

Meanwhile, at Port Stanley, now in wireless communication with all the rest of Admiral Sturdee’s squadron, the silence of the Kent, owing to her broken wireless, had begun to give rise to some alarm. “Kent, Kent, Kent” rang the invisible call, but there was no reply, and it was feared that she had been lost. It was perhaps characteristic that, in spite of this, she was the first of them all to reach port the next day. Of von Spee’s squadron only the Dresden remained, to be run to earth three months later. The Bristol and Macedonia, after capturing their crews, had sunk the Santa Isabel and the Baden; and the total British casualties in killed and wounded amounted to less than thirty.

___________________________________________

[1] As a matter of fact, the Scharnhorst’s ensign was not lowered, but, as Admiral Sturdee afterward remarked, “Von Spee met his fate like a brave Admiral, though our foe.”