Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Deeds That Won the Empire, by W. H. Fitchett (published 1897). All spelling in the original.

“Let us think of them that sleep

Full many a fathom deep

By thy wild and stormy deep,

Elsinore!”

—CAMPBELL

“I have been in a hundred and five engagements, but that of to-day is the most terrible of them all.” This was how Nelson himself summed up the great fight off Copenhagen, or the battle of the Baltic as it is sometimes called, fought on April 2, 1801. It was a battle betwixt Britons and Danes. The men who fought under the blood-red flag of Great Britain, and under the split flag of Denmark with its white cross, were alike the descendants of the Vikings. The blood of the old sea-rovers ran hot and fierce in their veins. Nelson, with the glories of the Nile still ringing about his name, commanded the British fleet, and the fire of his eager and gallant spirit ran from ship to ship like so many volts of electricity. But the Danes fought in sight of their capital, under the eyes of their wives and children. It is not strange that through the four hours during which the thunder of the great battle rolled over the roofs of Copenhagen and up the narrow waters of the Sound, human valour and endurance in both fleets were at their very highest.

Less than sixty years afterwards “thunders of fort and fleet” along all the shores of England were welcoming a daughter of the Danish throne as

“Bride of the heir of the kings of the sea.”

And Tennyson, speaking for every Briton, assured the Danish girl who was to be their future Queen—

“We are each all Dane in our welcome of thee.”

What was it in 1801 which sent a British fleet on an errand of battle to Copenhagen?

It was a tiny episode of the long and stern drama of the Napoleonic wars. Great Britain was supreme on the sea, Napoleon on the land, and, in his own words, Napoleon conceived the idea of “conquering the sea by the land.” Paul I of Russia, a semi-lunatic, became Napoleon’s ally and tool. Paul was able to put overwhelming pressure on Sweden, Denmark, and Prussia, and these Powers were federated as the “League of Armed Neutrality,” with the avowed purpose of challenging the marine supremacy of Great Britain. Paul seized all British ships in Russian ports; Prussia marched troops into Hanover; every port from the North Cape to Gibraltar was shut against the British flag. Britain, stood alone, practically threatened with a naval combination of all the Northern Powers, while behind the combination stood Napoleon, the subtlest brain and most imperious will ever devoted to the service of war. Napoleon’s master passion, it should be remembered, was the desire to overthrow Great Britain, and he held in the palm of his hand the whole military strength of the Continent. The fleets of France and Spain were crushed or blockaded: but the three Northern Powers could have put into battle-line a fleet of fifty great ships and twenty-five frigates. With this force they could raise the blockade of the French ports, sweep triumphant through the narrow seas, and land a French army in Kent or in Ulster.

Pitt was Prime Minister, and his masterful intellect controlled British policy. He determined that the fleets of Denmark and of Russia should not become a weapon in the hand of Napoleon against England; and a fleet of eighteen ships of the line, with frigates and bomb-vessels, was despatched to reason, from the iron lips of their guns, with the misguided Danish Government. Sir Hyde Parker, a decent, unenterprising veteran, was commander-in-chief by virtue of seniority; but Nelson, with the nominal rank of second in command, was the brain and soul of the expedition. “Almost all the safety and certainly all the honour of England,” he said to his chief, “is more entrusted to you than ever yet fell to the lot of a British officer.” And all through the story of the expedition it is amusing to notice the fashion in which Nelson’s fiery nature strove to kindle poor Sir Hyde Barker’s sluggish temper to its own flame.

The fleet sailed from Yarmouth on March 12, and fought its way through fierce spring gales to the entrance of the Kattegat. The wind was fair; Nelson was eager to sweep down on Copenhagen with the whole fleet, and negotiate with the whole skyline of Copenhagen crowded with British topsails. “While the negotiation is going on,” he said, “the Dane should see our flag waving every time he lifts up his head.” Time was worth more than gold; it was worth brave men’s lives. The Danes were toiling day and night to prepare the defence of their capital. But prim Sir Hyde anchored, and sent up a single frigate with his ultimatum, and it was not until March 30 that the British fleet, a long line of stately vessels, came sailing up the Sound, passed Elsinore, and cast anchor fifteen miles from Copenhagen. Nothing could surpass the gallant energy shown by the Danes in their preparation for defence, and Nature had done much to make the city impregnable from the sea.

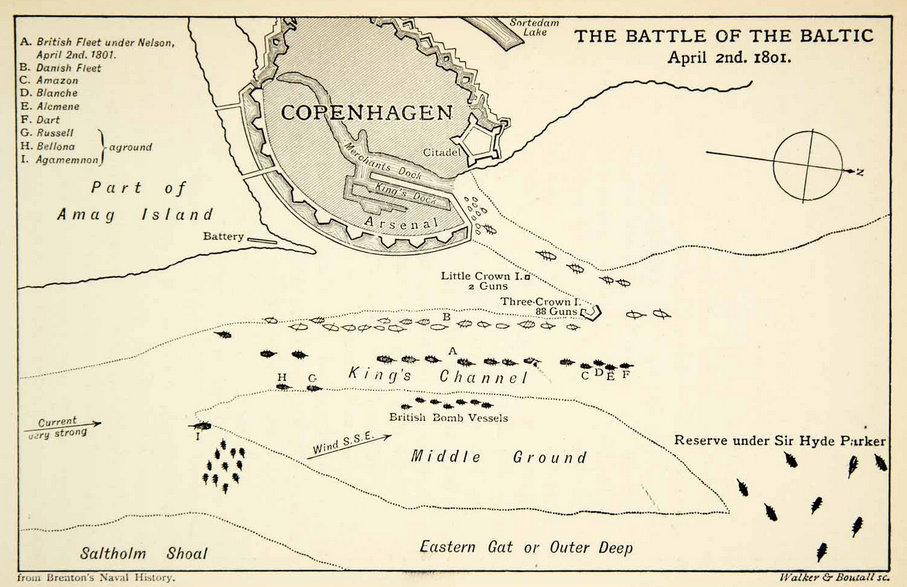

The Sound is narrow and shallow, a mere tangle of shoals wrinkled with twisted channels and scoured by the swift tides. King’s Channel runs straight up towards the city, but a huge sandbank, like the point of a toe, splits the channel into two just as it reaches the harbour. The western edge runs up, pocket-shaped, into the city, and forms the actual port; the main channel contracts, swings round to the south-east, and forms a narrow passage between the shallows in front of the city and a huge shoal called the Middle Ground. A cluster of grim and heavily armed fortifications called the Three-Crown Batteries guarded the entrance to the harbour, and looked right up King’s Channel; a stretch of floating batteries and line-of-battle ships, a mile and a half in extent, ran from the Three-Crown Batteries along the edge of the shoals in front of the city, with some heavy pile batteries at its termination. The direct approach up King’s Channel, together with the narrow passage between the city and the Middle Ground, were thus commanded by the fire of over 600 heavy guns. The Danes had removed the buoys that marked all the channels, the British had no charts, and only the most daring and skilful seamanship could bring the great ships of the British fleet through that treacherous tangle of shoals to the Danish front. As a matter of fact, the heavier ships in the British fleet never attempted to join in the desperate fight which was waged, but hung as mere spectators in the offing.

Meanwhile popular enthusiasm in the Danish capital was at fever-point. Ten thousand disciplined troops manned the batteries; but peasants from the farms, workmen from the factories, merchants from the city, hastened to volunteer, and worked day and night at gun-drill. A thousand students from the university enrolled themselves, and drilled from morning till night. These student-soldiers had probably the best military band ever known; it consisted of the entire orchestra of the Theatre Royal, all volunteers. A Danish officer, sent on some message under a flag of truce to the British fleet, was required to put his message in writing, and was offered a somewhat damaged pen for that purpose. He threw it down with a laugh, saying that “if the British guns were not better pointed than their pens they wouldn’t make much impression on Copenhagen.” That flash of gallant wit marked the temper of the Danes. They were on flame with confident daring.

Nelson, always keen for a daring policy, had undertaken to attack the Danish defences with a squadron of twelve seventy-fours, and the frigates and bomb-vessels of the fleet. He determined to shun the open way of King’s Channel, grope through the uncertain passage called the Dutch Deep, at the back of the Middle Ground, and forcing his way up the narrow channel in front of the shallows, repeat on the anchored batteries and battleships of the Danes the exploit of the Nile. He spent the nights of March 30 and 31 sounding the channel, being himself, in spite of fog and ice, in the boat nearly the whole of these two bitter nights. On April 1 the fleet came slowly up the Dutch Deep, and dropped anchor at night about two miles from the southern extremity of the Danish line. At eleven o’clock that night, Hardy—in whose arms Nelson afterwards died on board the Victory—pushed off from the flagship in a small boat and sounded the channel in front of the Danish floating batteries. So daring was he that he actually sounded round the leading ship of the Danish line, using a pole to avoid being detected.

In the morning the wind blew fair for the channel. Nelson’s plans had been elaborated to their minutest details, and the pilots of the fleet were summoned at nine o’clock to the flagship to receive their last instructions. But their nerve failed them. They were simply the mates or masters of Baltic traders turned for the moment into naval pilots. They had no charts. They were accustomed to handle ships of 200 or 300 tons burden, and the task of steering the great British seventy-fours through the labyrinths of shallows, with the tide running like a mill-race, appalled them. At last Murray, in the Edgar, undertook to lead. The signal was made to weigh in succession, and one great ship after another, with its topsails on the caps, rounded the shoulder of the Middle Ground, and in stately procession, the Edgar leading, came up the channel. Campbell in his fine ballad has pictured the scene:—

“Like leviathans afloat

Lay their bulwarks on the brine,

While the sign of battle flew

On the lofty British line.

It was ten of April morn by the chime;

As they drifted on their path

There was silence deep as death,

And the boldest held his breath

For a time.

But the might of England flushed

To anticipate the scene,

And her van the fleeter rushed

O’er the deadly space between.”

The leading Danish ships broke into a tempest of fire as the British ships came within range. The Agamemnon failed to weather the shoulder of the Middle Ground, and went ignobly ashore, and the scour of the tide kept her fast there, in spite of the most desperate exertions of her crew. The Bellona, a pile of white canvas above, a double line of curving batteries below, hugged the Middle Ground too closely, and grounded too; and the Russell, following close after her, went ashore in the same manner, with its jib-boom almost touching the Bellona’s taffrail. One-fourth of Nelson’s force was thus practically out of the fight before a British gun was fired. These were the ships, too, intended to sail past the whole Danish line and engage the Three-Crown Batteries. As they were hors de combat, the frigates of the squadron, under Riou—”the gallant, good Riou” of Campbell’s noble lines—had to take the place of the seventy-fours.

Meanwhile, Nelson, in the Elephant, came following hard on the ill-fated Russell. Nelson’s orders were that each ship should pass her leader on the starboard side, and had he acted on his own orders, Nelson too would have grounded, with every ship that followed him. The interval betwixt each ship was so narrow that decision had to be instant; and Nelson, judging the water to the larboard of the Russell to be deeper, put his helm a-starboard, and so shot past the Russell on its larboard beam into the true channel, the whole line following his example. That sudden whirl to starboard of the flagship’s helm—a flash of brilliant seamanship—saved the battle.

Ship after ship shot past, and anchored, by a cable astern, in its assigned position. The sullen thunder of the guns rolled from end to end of the long line, the flash of the artillery ran in a dance of flame along the mile and a half of batteries, and some 2000 pieces of artillery, most of them of the heaviest calibre, filled the long Sound with the roar of battle. Nelson loved close fighting, and he anchored within a cable’s length of the Danish flagship, the pilots refusing to carry the ship nearer on account of the shallow depth, and the average distance of the hostile lines was less than a hundred fathoms. The cannonade raged, deep-voiced, unbroken, and terrible, for three hours. “Warm work,” said Nelson, as it seemed to deepen in fury and volume, “but, mark you, I would not be elsewhere for thousands.” The carnage was terrific. Twice the Danish flagship took fire, and out of a crew of 336 no fewer than 270 were dead or wounded. Two of the Danish prams drifted from the line, mere wrecks, with cordage in rags, bulwarks riddled, guns dismounted, and decks veritable shambles.

The battle, it must be remembered, raged within easy sight of the city, and roofs and church towers were crowded with spectators. They could see nothing but a low-lying continent of whirling smoke, shaken with the tumult of battle, and scored perpetually, in crimson bars, with the flame of the guns. Above the drifting smoke towered the tops of the British seventy-fours, stately and threatening. The south-east wind presently drove the smoke over the city, and beneath that inky roof, as under the gloom of an eclipse, the crowds of Copenhagen, white-faced with excitement, watched the Homeric fight, in which their sons, and brothers, and husbands were perishing.

Nothing could surpass the courage of the Danes. Fresh crews marched fiercely to the floating batteries as these threatened to grow silent by mere slaughter, and, on decks crimson and slippery with the blood of their predecessors, took up the fight. Again and again, after a Danish ship had struck from mere exhaustion, it was manned afresh from the shore, and the fight renewed. The very youngest officer in the Danish navy was a lad of seventeen named Villemoes. He commanded a tiny floating battery of six guns, manned by twenty-four men, and he managed to bring it under the very counter of Nelson’s flagship, and fired his guns point-blank into its huge wooden sides. He stuck to his work until the British marines shot down every man of his tiny crew except four. After the battle Nelson begged that young Villemoes might be introduced to him, and told the Danish Crown Prince that a boy so gallant ought to be made an admiral. “If I were to make all my brave officers admirals,” was the reply, “I should have no captains or lieutenants left.”

The terrific nature of the British fire, as well as the stubbornness of Danish courage, may be judged from the fact that most of the prizes taken in the fight were so absolutely riddled with shot as to have to be destroyed. Foley, who led the van at the battle of the Nile, was Nelson’s flag-captain in the Elephant, and he declared he burned fifty more barrels of powder in the four hours’ furious cannonade at Copenhagen than he did during the long night struggle at the Nile! The fire of the Danes, it may be added, was almost as obstinate and deadly. The Monarch, for example, had no fewer than 210 of its crew lying dead or wounded on its decks. At one o’clock Sir Hyde Parker, who was watching the struggle with a squadron of eight of his heaviest ships from the offing, hoisted a signal to discontinue the engagement. Then came the incident which every boy remembers.

The signal-lieutenant of the Elephant reported that the admiral had thrown out No. 39, the signal to discontinue the fight. Nelson was pacing his quarterdeck fiercely, and took no notice of the report. The signal-officer met him at the next turn, and asked if he should repeat the signal. Nelson’s reply was to ask if his own signal for close action was still hoisted. “Yes,” said the officer. “Mind you keep it so,” said Nelson. Nelson continued to tramp his quarter-deck, the thunder of the battle all about him, his ship reeling to the recoil of its own guns. The stump of his lost arm jerked angrily to and fro, a sure sign of excitement with him. “Leave off action!” he said to his lieutenant; “I’m hanged if I do.” “You know, Foley,” he said, turning to his captain, “I’ve only one eye; I’ve a right to be blind sometimes.” And then putting the glass to his blind eye, he exclaimed, “I really do not see the signal!” He dismissed the incident by saying, “D—— the signal! Keep mine for closer action flying!”

As a matter of fact, Parker had hoisted the signal only to give Nelson the opportunity for withdrawing from the fight if he wished. The signal had one disastrous result—the little cluster of frigates and sloops engaged with the Three-Crown Batteries obeyed it and hauled off. As the Amazon, Riou’s ship, ceased to fire, the smoke lifted, and the Danish battery got her in full sight, and smote her with deadly effect. Riou himself, heartbroken with having to abandon the fight, had just exclaimed, “What will Nelson think of us!” when a chain-shot cut him in two, and with him a sailor with something of Nelson’s own genius for battle perished.

By two o’clock the Danish fire began to slack. One-half the line was a mere chain of wrecks; some of the floating batteries had sunk; the flagship was a mass of flames. Nelson at this point sent his boat ashore with a flag of truce, and a letter to the Prince Regent. The letter was addressed, “To the Danes, the brothers of Englishmen.” If the fire continued from the Danish side, Nelson said he would be compelled to set on fire all the floating batteries he had taken, “without being able to save the brave Danes who had defended them.” Somebody offered Nelson, when he had written the letter, a wafer with which to close it. “This,” said Nelson, “is no time to appear hurried or informal,” and he insisted on the letter being carefully sealed with wax. The Crown Prince proposed an armistice. Nelson, with great shrewdness, referred the proposal to his admiral lying four miles off in the London, foreseeing that the long pull out and back would give him time to get his own crippled ships clear of the shoals, and past the Three-Crown Batteries into the open channel beyond—the only course the wind made possible; and this was exactly what happened. Nelson, it is clear, was a shrewd diplomatist as well as a great sailor.

The night was coming on black with the threat of tempest; the Danish flagship had just blown up; but the white flag of truce was flying, and the British toiled, as fiercely as they had fought, to float their stranded ships and take possession of their shattered prizes. Of these, only one was found capable of being sufficiently repaired to be taken to Portsmouth. On the 4th Nelson himself landed and visited the Crown Prince, and a four months’ truce was agreed upon. News came at that moment of the assassination of Paul I, and the League of Armed Neutrality—the device by which Napoleon hoped to overthrow the naval power of Great Britain—vanished into mere space. The fire of Nelson’s guns at Copenhagen wrecked Napoleon’s whole naval policy.

It is curious that, familiar as Nelson was with the grim visage of battle, the carnage of that four hours’ cannonade was too much for even his steady nerves. He could find no words too generous to declare his admiration of the obstinate courage shown by the Danes. “The French and Spanish fight well,” he said, “but they could not have stood for an hour such a fire as the Danes sustained for four hours.”

Wooden ships and iron men, indeed. Thank you for posting stories like this.

“the subtlest brain and most imperious will ever devoted to the service of war”

“These student-soldiers had probably the best military band ever known”

“always keen for a daring policy”

It is this little pieces of side narration that the author slips in that really made this passage a joy to read in particular. Been forever since I have read a modern history book, but these little snippets always seem to make the older histories you somehow keep bringing us come alive. Blending the line between historian and author.