Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Khartoum Campaign, 1898, by Bennet Burleigh (published 1899). All spelling in the original.

The supreme and greatest victory ever achieved by British arms in the Soudan has been won by the Sirdar’s ever-victorious forces, after one of the most picturesque battles of the century. At last! After fifteen vexatious years spent in trying to get here, an Anglo-Egyptian army has recovered Khartoum and occupied Omdurman. Gordon has been avenged and justified. The dervishes have been overwhelmingly routed, Mahdism has been “smashed,” whilst the Khalifa’s capital of Omdurman has been stripped of its barbaric halo of sanctity and invulnerability. Striking and dramatic as has been the manner in which the ending of the curse of the Soudan has come about, the tale need lose none of its force by being simply told. The grandeur of the plain story requires no straining after catchwords. Of those who with Sir Herbert Stewart’s desert column toiled and fought to reach Metemmeh in January 1885, less than a dozen are with the Sirdar’s army, and of these but three, including the writer, were correspondents. But to the narrative of the battle which, at a stroke, has broken down the potent savage barriers of blood and cruelty, and re-opened the heart of the great African continent to the sweetening influences of civilised government.

Storm and cloud had passed. The moon rose early on the night of 1st September. It shone brightly over and around our bivouac, south of Kerreri village, or near Um Mutragan, according to the cartographers. The north end of our camp lines approached the river just 500 yards south of the ruined dervish redoubt of Kerreri. Sentinels were posted along the irregular-shaped triangle, or, shall I call it, broken semi-circle, within which the army lay. The sentries had a fair range of view to their front. Men on the lookout also occupied the roofs of the few native mud-huts at the south-western corner of the camp. Four Jaalin scouts were sent forward to Surgham Hill to listen, and to apprise the troops of any movement on the part of the Khalifa’s army. Other friendlies lay about outside, hearkening and watching, to warn us of any attempt of the enemy to surprise the zereba. The sentries were bid to shoot at any man rushing singly upon him, and to fire upon large bodies advancing at the double. Men running in, however, in pairs, were either to be challenged or allowed to come in without being fired on. Such was the simple yet ample arrangement. To anticipate somewhat, it so happened that about midnight there was some firing, and the four Jaalin “smellers of danger and dervishes” upon Jebel Surgham came sprinting in, a four-in-hand, and cleared the broad cut mimosa hedge that was piled before the lines of Gatacre’s division, at a bound. The time they made broke all records.

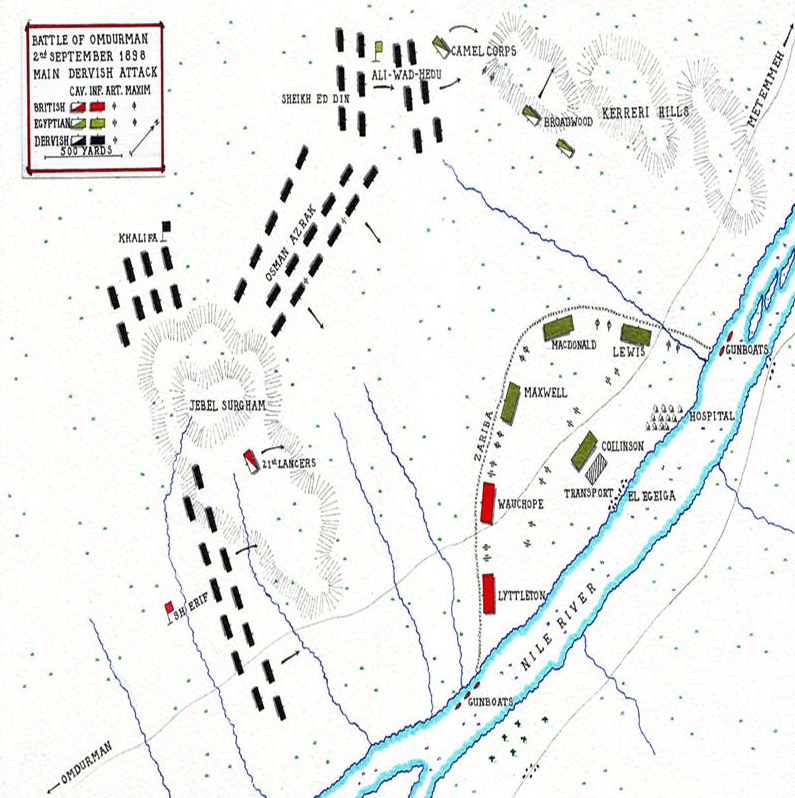

From the north to the south end along the river the camp was about one mile in length, and its greatest width about 1200 yards. There were a few mud-huts within the space enclosed by mimosa and the double line of shallow shelter-trenches. The cut bushes were piled in front of the British troops, who were facing Omdurman and the south; the trenches covered the approach from the west and north where the Khedivial troops stood on guard. Neither extremity of the lines of defence, zereba or trench, quite extended to the river. Openings of about thirty to fifty yards were left. Besides these there were other small passage-ways left open during daylight, but closed at night. Near the river facing south the ground was rough, and there were several huts, so that the security of the camp was not imperilled by the failure to carry the hedge or trenches to the Nile’s brink. Lyttelton’s brigade were placed upon the left south front. Wauchope’s men continued the line to the right. In the south gap were three companies of the 2nd Battalion Rifle Brigade, their left resting on the river. On their immediate right were three batteries—the 32nd Field Battery of English 15-pounders, under Major Williams; two Maxim-Nordenfeldt mountain batteries, 12½-pounders, respectively under Captains Stewart and de Rougemont; and six Maxims under Captain Smeaton. Later on these guns and Maxims during the first stage of the battle—for the action resolved itself into a double event ere the combat ceased—were wheeled out until they were firing almost at right angles to the zereba line. On the right of the guns, in succession, were the remainder of the Rifles, the Lancashire Fusiliers, the Northumberland Fusiliers, and the Grenadier Guards. In the interval between General Lyttelton’s brigade and General Wauchope’s, which stood next to it, were two Maxims. Then came the Warwicks, Camerons, Seaforths, and Lincolns. To the Lincolns’ right, where the trenches began and the line faced nearly west, was Colonel Maxwell’s brigade. Between Wauchope’s and Maxwell’s brigades were two Maxims, and, I think, for a time during the first attack made by the dervishes, the two-gun mule battery of six-centimetre Krupp guns. To complete the tale of the guns placed for defending the camp, there was Major Lawrie’s battery of Maxim-Nordenfeldts on the right of Maxwell’s brigade next Macdonald’s, and on the north side, near the right of the position facing west, Major Peake’s battery of Maxim-Nordenfeldts. These guns had done so well at the Atbara, that the Sirdar promptly increased his artillery by adding three batteries of that class. Maxwell’s brigade was composed of three Soudanese and one Egyptian battalion, viz., 8th Egyptian, and 12th, 13th, and 14th Soudanese. Farther north, to the right of Colonel Maxwell’s men, was Lewis Bey’s brigade of Egyptian troops—the 3rd, 4th, 7th, and 15th Battalions. The 15th Battalion was a fine lot, mostly reservists. Upon the farthest west and northern face of the protected camp was. Colonel Macdonald’s oft-tried and famous fighting brigade, made up of the 9th, 10th, and 11th Soudanese, with the true-as-steel 2nd Egyptians. Within the wall of hedge, trenches, and armed infantry, in reserve, was another brigade, the 4th Khedivial, commanded by Major Collinson. It was made up of the 1st, 5th, 17th, and 18th Egyptian battalions. The two last-named were relatively newly-raised regiments, but were composed of fine soldierly-looking fellaheen. The divisional brigade and battalion commanders and staff were:—British division, Major-General Gatacre commanding; staff: Major Robb, D.A.G.; Captain R. Brooke, A.D.C.; Lieuts. Cox and Ingle, orderly officers; Surgeon-Colonel MacNamara, P.M.O. First British Infantry brigade, Brigadier-General A. Wauchope; staff: Major Doyle Snow, brigade-major; Captain Rennie, A.D.C.; Surgeon-Lieut.-Colonel Sloggett, P.M.O. Second brigade, Brigadier-General, Hon. N. G. Lyttelton; staff: Major A Court, brigade-major; Captain Henderson, A.D.C. Surgeon-General W. Taylor was the principal medical officer of the British division. Lieut.-Colonel C. J. Long, R.A., commanded all the artillery. Khedivial troops—Infantry division, Major-General A. Hunter, commanding; staff: Surgeon-Colonel Gallwey, P.M.O.; Captain Kincaid, D.A.G.; Lieut. Smythe, A.D.C. 1st brigade, Brigadier H. A. Macdonald; Major C. Keith Falconer, brigade-major. 2nd brigade, Brigadier Lewis; 3rd brigade, Brigadier Maxwell; 4th brigade, Brigadier Collinson.

The battalion commanders of British troops were:—Grenadier Guards, Lieut.-Colonel Villiers-Hatton; Lancashire Fusiliers, Lieut.-Colonel Collingwood; Northumberland Fusiliers, Lieut.-Colonel C. G. C. Money; Rifle Brigade, Colonel Howard; Warwickshires, Lieut.-Colonel Forbes; Lincolns, Lieut.-Colonel Louth; Camerons, Lieut.-Colonel G. L. C. Money; Seaforths, Lieut.-Colonel Murray. Those of the Khedivial battalions were:—Macdonald’s brigade, Majors Pink, 2nd Egyptian; Walter, 9th Soudanese; Nason, 10th Soudanese; Jackson, 11th Soudanese. Lewis’s brigade, Majors Sellem, 3rd Egyptian; Sparkes, 4th Egyptian; Fatby Bey, 7th Egyptian; and Major Hickman, 15th Egyptian. Maxwell’s brigade, Majors Kalousie, 8th Egyptian; Townsend, 12th Soudanese; Smith-Dorian, 13th Soudanese; Shekleton, 14th Soudanese. Collinson’s brigade, Captains (O.C.’s) Bainbridge, 1st Egyptian; Abd El Gervad Borham, 5th Egyptian; Bunbury, 17th Egyptian; and Matchell, 18th Egyptian.

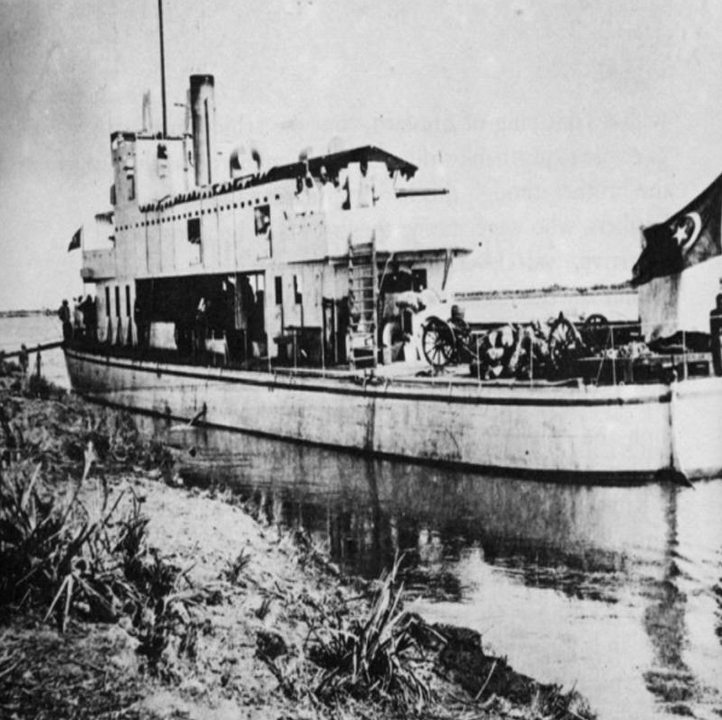

The troops were ranged two deep in front with a partial second double line or supports placed twenty yards or so behind them. These assisted in the fight to pass ammunition to the firing line and carry back the dead and wounded. Somewhat removed from the zereba and trenches, and nearer the Nile were the hospitals, the transport, the stores, nearly 3000 camels, and about 500 mules. The Egyptian cavalry and camelry were picketed at the north of the camp, and the 21st Lancers at the south end, both being within the lines. All along the river’s bank beside the camp were moored the gunboats, steamers and barges, with a fleet of a hundred or more native sailing boats, at once a means of defence and a supply column. The gunboat “Melik” was moored a few hundred yards south of where the Rifles were posted. Occasionally the flotilla flashed their search-lights upon Jebel Surgham, and swept the scrub and desert in front of the troops. The enemy’s scouts, however, were never disclosed in the radii of the electric beams. In fact, the first notice we had that the dervishes were about to inspect our environment was the impetuous incoming of our friendlies from Jebel Surgham and the cracking of snipers’ guns in the bush mingled with the buzzing of bullets overhead. A battalion rose quietly from the ground, for the troops slept clear of the hedge, and went forward a few paces to man the zereba. On learning what was actually taking place they returned to their blankets and to sleep.

For all the row the dervish spies, snipers and others made, the army was not really disturbed. Once more we had to thank fortune that the enemy made no vigorous attempt to assail the camp during the night. True, earlier in the evening a few badly-directed rifle-shots had come whistling across the zereba. Prowling dervish scouts had even occasionally crept close enough to draw upon themselves the attention of our double sentries and alert patrols. A small section volley at one period of the night was fired at a knot of the enemy’s would-be bush-whackers. The unusual rattle of musketry caused an incipient alarm in one of the battalions. Tommy, however, behaved well, collectively, never stirring, but waiting “for orders.” The peace of the night hours was, I repeat, never seriously broken, the Anglo-Egyptian army enjoying their needed sleep. After midnight things quieted down and from the dervish camp no sound was carried to us by the soft south wind. All was absolutely still in that direction. The noggara or war-drum was a dead thing, beating not to quarters, as we had heard it during the day when out with the cavalry. Nor was the deep-bayed booming of the ombeyas, or elephant horns, re-echoing to rally the tribesmen under their leaders’ banners.

It was 3.40 a.m. on 2nd September when the bugles called the 22,000 men of the Sirdar’s army from slumber. Quickly the troops were astir, and the camp full of bustling preparation. It was given out that we were not to move forward quite as early as usual. But circumstances alter cases, and very soon loads and saddles were adjusted with extra care. Everything was made as trim as possible, and belts were buckled tightly for action. There was a sense and expectancy of coming battle abroad, and an eager desire permeating all ranks to have it out with the dervishes then or never. It had come at length to be generally accepted that the enemy would not bolt nor slip through our fingers, but would accept the gage of battle which the Sirdar meant shortly to give him. We were going to march out, attack, and storm the Khalifa and his great army in their chosen lines and trenches. In a way we felt half-heartedly grateful to our sportsmanlike enemy for not having harassed our marches or bivouacs. We were, within the next hour or so, to have yet more to thank the dervishes and their Khalifa for. Truly Abdullah was amazingly ignorant of war tactics, or astoundingly confident in the prowess of his arms. From the reckless, magnificent manner in which the dervishes comported themselves in the earlier stages of the fight that ensued, I incline to the belief that the Khalifa and his men, true to their crass, credulous notions, were overweeningly confident in themselves. A fatal fault, they underrated their opponents. His Emirs, Jehadieh, and Baggara had so often proved themselves invincible in their combats against natives of the Soudan, that they had come to hold that none would face their battle shock. There was pride of countless triumphs, and the long enjoyment of despotic lordship that hardened their wills and thews to win victory or perish. I failed later to see the old fanaticism that once made them, though pierced through and through with bayonet or sword, fight till the last heart-throb ceased. Let me not be misunderstood. Despite their possible doubts about the Khalifa’s divine mission, the dervish army fought with courage and dash until they were absolutely broken. Their personal hardihood bravely compared with the days of Tamai and Abu Klea. It was when the fight was nearly over that there were evidences of that of which there was so little in the old days, viz., that a large remnant would accept life at our hands. Again, as the sequel showed, the Sirdar’s star was in the ascendant.

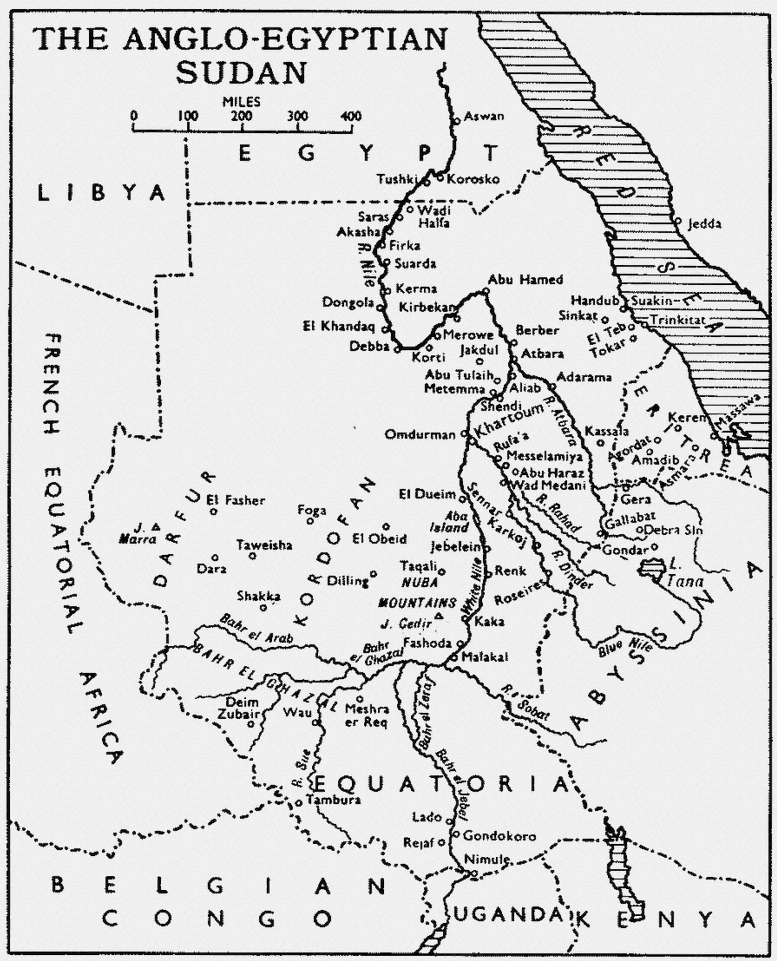

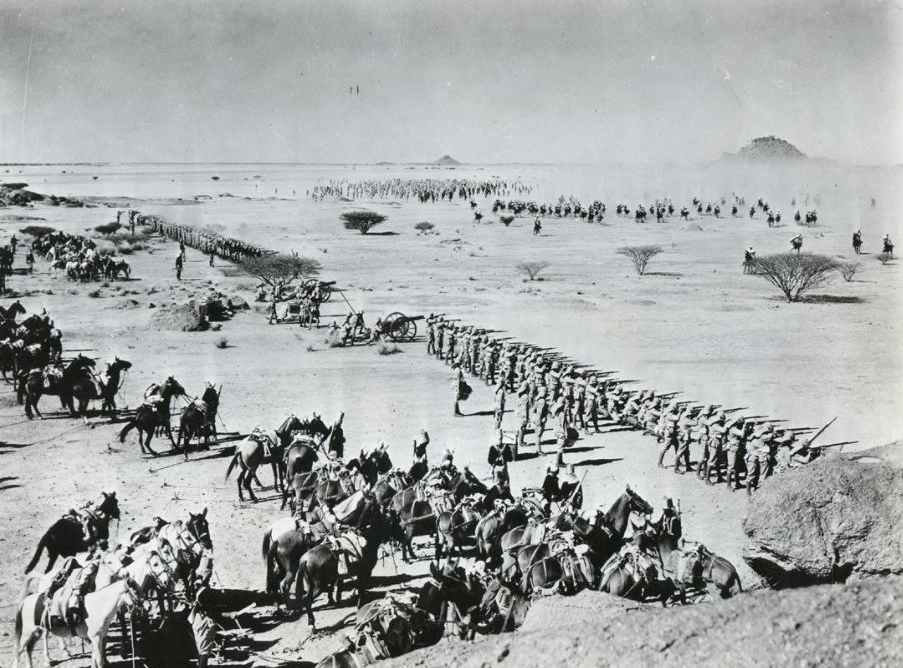

Everything was in readiness in our camp by 5 a.m. Camels, horses, mules, and donkeys had been watered and fed, and the men had disposed of an early breakfast of cocoa or tea, coarse biscuit, and tinned meat. Infantry and artillery had made sure of their full supply of ammunition, and the reserve was handy to draw more from. Tommy Atkins carried 100 rounds of the new hollow-nosed Lee-Metford cartridges. Behind him were mules loaded with a further twenty rounds for him. The Khedivial soldiers had 120 rounds of Martini-Henry cartridges. To hark back: at 4.30 a.m., ere dawn had tinged the east, the Sirdar bade Colonel Broadwood, commanding the Egyptian cavalry, send out two squadrons to ascertain what the enemy was about. Thereupon one squadron rode off to the hills on the west—known locally as South Kerreri jebels, but marked on most maps as Um Mutragan. Besides being misnamed, they are plotted in out of place and as if the range trended east and west. It runs nearly north and south. Kerreri hills were low and black, like most of the jebels thereabout. They stand fully two miles west of the Nile. Another squadron, under Captain Hon. E. Baring, proceeded south to Jebel Surgham, the low hill, about one mile in front of the British division. I have written about it before. Surgham was used for heliograph and flag signalling on the 1st, the previous day, and is the last of the detached hills or ranges lying near the river on the north towards Omdurman. The squadron going west soon reached South Kerreri hill, and reported that the enemy were still in camp. It was early, and not clear daylight, and the distance to the Khalifa’s encampment was greater from South Kerreri hill than that from Jebel Surgham to where the dervishes lay in the bush and hollows around Wady Shamba. Captain Baring’s party, on the other hand, met with small patrols of the enemy near Jebel Surgham. Turning the hill at a few minutes past five o’clock, in the yet slanting daylight, he at once detected that the Khalifa’s army, which had apparently been largely reinforced during the night, was marching forward to attack us. Gallopers and orderlies came riding back furiously with the news for the Sirdar. Sir Herbert Kitchener, Major-General Rundle, and the whole headquarters staff were already mounted. Colonel Broadwood was despatched to verify the startling report, and to bring in further particulars. Meantime the preparations on our side for an advance were suspended, and guns, Maxims, and infantry moved up and wheeled into positions upon the firing line. Ominous was that silent march of six paces to their front made by the British infantry to get close to the zereba and the clearing for action of Maxims and cannon, and the examining of the breeches of the Lee-Metfords. For the first time the magazines were to be used. The Khedivial soldiers swarmed into their trenches. Anon, the Tommy Atkinses were ordered to lie down behind their hedge of cut mimosa to rest and wait. From a little distance, no doubt, our camp looked silent, deserted, and as void of danger as any other part of the plain. Standing a few yards behind each command were placed in reserve sometimes two, sometimes three companies, which had been withdrawn from the battalion on their immediate front. These reserves were to fill gaps or stiffen the firing line, should it be too closely pressed. With the companies in reserve were the stretchers and bearers. A little farther back was the British divisional field hospital, planted in a congeries of native dirt-huts. The scattered mud-huts within the lines afforded excellent cover to the sick and wounded, as well as a degree of protection for the camels, horses, mules, and donkeys picketed near the middle ground of the camp.

Colonel Broadwood returned swiftly with the news that the whole dervish army was really in motion, and that if it held upon its apparent course its right wing would pass about 500 yards to the west of Jebel Surgham. That hill was within easy shelling distance from the gunboats, and the solitary instance of prudence that the dervishes had so far shown was to keep far enough inland to render the assistance of the flotilla of as little help as possible to us. Some there were who thought that Jebel Surgham should have been made the central stronghold of our camp, and that the army ought to have slept behind it on the previous night. The wisdom of that suggestion was most doubtful. Where we were the gunboats could more easily cover the whole position.

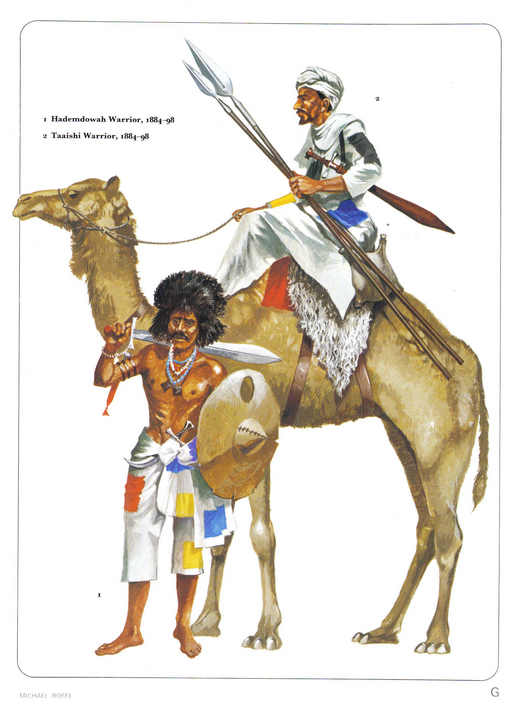

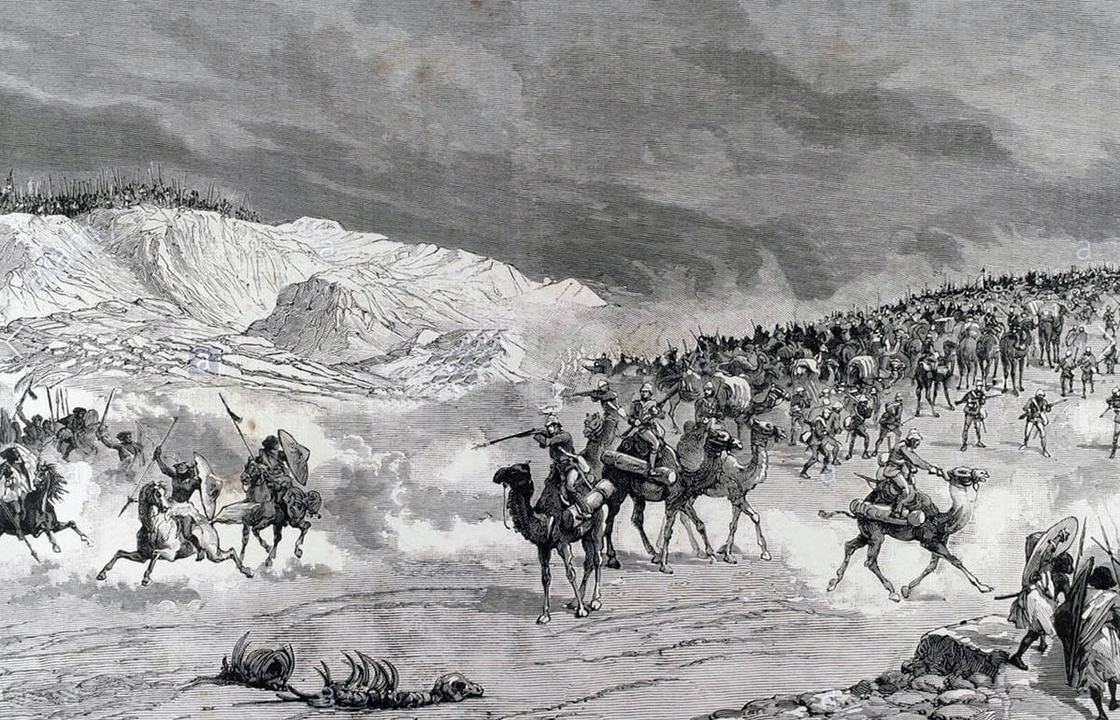

It was about 5 a.m. when the 21st Lancers started forward to undertake their daily task of scouting and covering the left flank of the Sirdar’s army. They reached Jebel Surgham a few minutes later and relieved Captain Baring’s squadron, which at once rode away and joined the remaining squadrons of Egyptian cavalry on South Kerreri hill, whither Colonel Broadwood had by that time gone with his troopers. Every inch of Surgham hill and the yellow sand ridges, gravel mounds, and shallow khors to the south and west of it had been explored by the Lancers the day before. Riding straight out from the zereba ere the faintly-glowing dawn had come, I joined the Lancers on Surgham. A dismounted squadron occupied part of the southern slopes, a troop or more were on the higher points and summit keeping sharp eyes on the enemy. Flag-signallers were preparing for work at the place where the day before helios had been busy flashing news from gunboats and cavalry to the headquarters. As I climbed the rugged slopes of Jebel Surgham leading my horse, I heard a mighty rumbling as of tempestuous rollers and surf bearing down upon a rock-bound shore. When I had gone but a few strides farther there burst upon my sight a moving, undulating plain of men, flecked with banners and glistening steel. Who should count them? They were compact, not to be numbered. Their front from east to west extended over three miles, a dense mass flowing towards us. It was a great, deep-bodied flood, rather than an avalanche, advancing without flurry, solidly, with presage of power. The sound of their coming grew each instant louder, and became articulate. It was not alone the reverberation of the tread of horses and men’s feet I heard and seemed to feel as well as hear, but a voiced continuous shouting and chanting—the dervish invocation and battle challenge, “Allah el Allah! Rasool Allah el Mahdi!” they reiterated in vociferous rhymed rising measure, as they swept over the intervening ground. Their ranks were well kept, the serried lines marching with military regularity, with swaying of flags and brandishing of big-bladed, cruel spears and two-edged swords. Emirs and chiefs on horseback rode in front and along the lines, gesticulating and marshalling their commands. Mounted Baggara trotted about along the inner lines of footmen. There were apparently as before five great divisions in the dervish army. The Khalifa’s corps was near the right centre, with his son, Sheikh Ed Din’s division on his left. The relative positions of the great chiefs were readily recognisable by their banners, which were carried in the midst of their chosen body-guards. Khalifa Abdullah’s great black banner, black-lettered with texts from the Koran and the Mahdi’s sayings, was upheld by his Mulazimin. It flew, spread out, flaunting in the wind, acclaimed by his followers. The flag was about two yards square, and was supported on a 20-feet bamboo pole, ornamented at top with a silver bowl and spandrel, as well as a tassel. The force marching with it must have numbered 20,000 armed men, besides servants and followers. His son, Osman, known as Sheikh Ed Din, and the nominal commander-in-chief of the dervish armies, led into battle a division of the Jehadieh (riflemen) and spearmen, together 15,000 strong. His force was ranged under blue, green, yellow, and white banners. With him was Khalil, the second Khalifa, Osman Azrak, Emir Yunis, Abdel Baki, and other noted chiefs of the Baggara. Yacoub, the notorious brother of the Khalifa Abdullah, commanded the big column upon his relative’s right hand. Still farther to their right were the divisions led by Wad Helu and Wad Melik. The joint forces of these twain probably numbered 12,000 or 14,000 men. Besides the main army there was a second line, possibly made up from the Omdurman populace, with a baggage train of camels and donkeys. I found out subsequently that the enemy were amply provisioned. Camels and donkeys carried water and grain, mostly dhura, for the Khalifa’s army. The dervishes, as a rule, had their goatskin wallets filled with grain, onions, and a piece of roasted meat.

The battle of Omdurman began at 5.30 a.m. with a salvo of six guns from Major Elmslie’s battery on the east Nile bank. They were fired from the 5-inch howitzers, which sent a half-dozen of 50-lb. Lyddite shells hurtling around the tomb and the Khalifa’s quarters. Like a spouting volcano, clouds of flame, stones, and dust burst from out the city. The line of strong forts before the town and upon Tuti island had been silenced by them and the gunboats the previous day. Although the dervishes had built stout works, and had plenty of cannon and ammunition, they made a wretchedly bad stand against the gunboats, injuring none of them. The overpowering weight as well as the accuracy of our steamers’ fire ended the naval part of the battle almost as soon as it was begun. Quick-firers and Maxims were trained to bear into the embrasures of the Khalifa’s forts. As a consequence, the enemy’s gunners were only able to fire a few wild rounds at the vessels. Jealous and suspicious of everyone, Abdullah left his arsenal full of unemployed batteries, Krupps, and machine guns, and only took three of either of the latter weapons with him into the field against us. After the labour too of taking them there, he made but little use of them. As I learned, the Greeks, some thirty-five, and all able-bodied men, had to march out of Omdurman and follow the Khalifa to battle. I by no means, I think, over-estimate the enemy’s numbers when I state that there were 50,000 dervishes of sorts who advanced against us, sworn to leave not a single soul alive in the Sirdar’s army. Abdullah, professedly sanguine of success, had bade the mollahs and others attend him at noon prayers in the mosque and Mahdi’s tomb, where he would go to worship immediately after his victory. He had returned into town, and spent part of the night of 1st and 2nd September in his own house.

The gunboats, which had gone on that morning, joined in the renewed bombardment of Omdurman, begun by Major Elmslie. But it was only for a short space, for the Sirdar recalled the steamers by signal to assist in repelling the attack when it was seen the Khalifa meant giving battle. Three squadrons of Lancers halted on the northern side of Jebel Surgham. A troop of them pushed on to the sandy ridges south-west of Surgham hill. Part of them dismounted, and with much hardihood began firing at about 1000 yards’ range at the oncoming dervishes. It was as if a few men afoot were seeking to interpose to hold back the invading ocean. Instantly dervish riflemen and horsemen shot out from the Khalifa’s lines and came streaming to engage the handful of troopers. The skirmishing Lancers desisted, mounted, and rode back to their main body. Of those of the Lancers who stood it out longest were the groups upon the top of Surgham and upon its eastern side. Colonel Martin got his four squadrons together as the dervishes drew in towards him. The enemy’s right was now thrown forward, facing straight for the angle of the camp where the British division stood. At a swinging gait came the vast army of Mahdism. I was still near Surgham and believed that I could discern the Khalifa himself in the centre of a jostling, excited throng of footmen and horsemen. He was seated upon a richly caparisoned Arab steed, guarded on all sides by stalwart natives armed with rifles and swords. A troop of mounted Emirs in front and a big retinue of Baggara and other chiefs on horseback riding behind surely proclaimed him to be Abdullah, the Mahdi’s successor. Far before him was borne his terrible black banner. Around him religious dervishes screamed, gesticulated, and shouted “Allah’s” name, confident that they had come out to see the annihilation of the invading infidels. Had it not been long foretold that the victorious battle would be fought at Kerreri, which ever after should be known among the faithful as “the death-field of the infidels”? Were not the white stones there already to mark our graves? I was fortunate to be able to scan the nearest of the dervish columns, from a distance of but 800 yards. The battle was about to open in fierce earnest. Away went the Lancers at the gallop, back to the zereba, but, edging towards the river, to clear our infantry’s front and line of fire. It was around the left of the 2nd battalion of the Rifle Brigade that the troopers passed in. I took a somewhat shorter, hasty cut, entering the zereba near where the three batteries stood, on the British left. Away off upon and under Um Mutragan, the Egyptian mounted troops, the nine squadrons of cavalry, eight companies of the Camel Corps, and the horse artillery, all under Colonel Broadwood, were pluckily endeavouring to tackle the left wing of the Khalifa’s forces. They held on, perhaps, too long; at any rate, until most of them were in a position of serious danger. As their fight and the more important general action happened at the same time, I must defer further description of it for the moment.

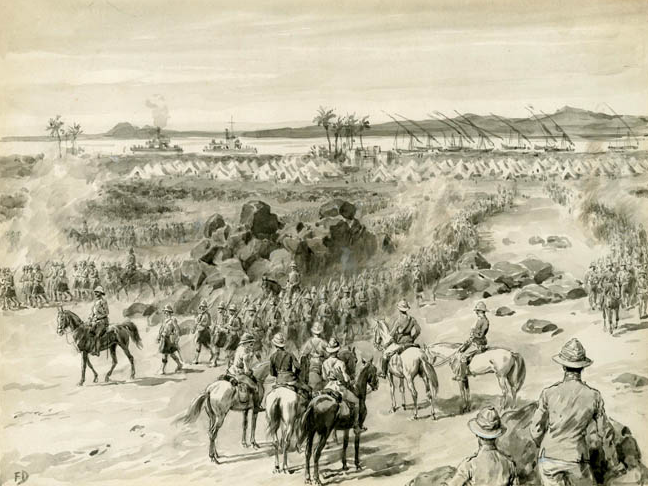

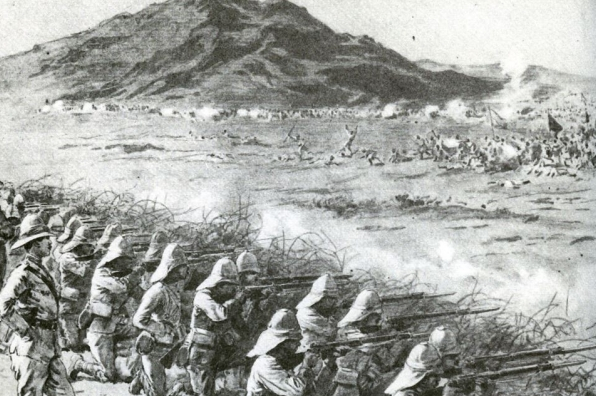

It was a magnificent spectacle that rose before the Sirdar’s army as the dervish columns came sweeping into view, filling the landscape between Surgham and Um Mutragan. In that great multitude were gathered the fiercest, most sanguinary body of savage warriors the world has ever held or known. Arabs and blacks, chosen by Abdullah himself, picked out because of their tried courage, strength, and devotion—the flower of the fighting Soudan tribes. Under other conditions Abdullah’s army might have matched itself to win against double their number of any men similarly armed. Fearless of danger, agile yet strong, each man carried with him into the fight the conviction that the Khalifa would conquer. A great shout of exultation went up from the dervish legions when they saw, ranged in the low ground before them, the Sirdar’s, small army, their imagined prey. There was a mighty waving of banners and flashing of steel when, breaking into a run, they bent forward to close upon us. The British division rose to their feet to be ready, and the Khedivial troops closed up their ranks. There was a murmur of satisfaction from Gatacre’s division and real cries of delight from the black troops on seeing the enemy were coming to attack. Never was there a grander, more imposing militant display seen than when the great dervish army rushed to engage, heedless of life or death. In an instant the Sirdar, who stood near the right of Wauchope’s brigade, passed an order for the three batteries on the left —Major Williams’, Stewart’s, de Rougemont’s—to open fire. The guns were laid at 2800 yards, a range the delight of gunners, and sighted to the west of Surgham, where the black flag and the largest mass of the enemy were. The hour was 6.35 a.m. Almost at the first shot the true range was found. Quick as thought thereafter the eighteen guns on our left began raining fire, iron, and lead upon the leading and main columns of the enemy. Two batteries to the right and many of the Maxims added to the fury of the fearful death-dealing storm bursting over and amongst the dervish ranks. The long 15-pounder English field cannon hit with the precision of match rifles, and were discharged as though they had been quick-firing guns. As for the stinging Maxim-Nordenfeldts, with their big single and bigger double shells, they bucked and jumped like kicking horses, yet were fired so fast that the barrels must have been well-nigh red-hot. The air was torn with hurtling shell at the first awful salvo, when shrapnel burst in all directions, smiting the dervishes as with Heaven’s thunderbolts, and strewing the ground with maimed and dead. The leading columns paused as if they had received a shock, or had stopped to catch breath. Hundreds had been slain in that one discharge, and the fire was rapidly increasing, not slackening. Disregarding their dead and wounded, the dervishes closed their ranks as with one accord, and came on with fresh energy. Their banner-bearers and the Baggara horsemen pushed to the front, doubtless to further encourage the still dauntless footmen. Surely there never was wilder courage displayed. In the face of a fire that mowed down battalions and smashed great gaps into their columns they flinched not nor turned. Noticing the enemy’s persistency, the Sirdar sent bidding General Lyttelton try them with long-range volleys from the Lee-Metfords. Major Lord Edward Cecil took the message, and Lieutenant H. M. Grenfell got the range from the gunners. The Grenadier Guards, who had the honour of being the first of our infantry to engage, were ordered to fire section volleys to their right at the Khalifa’s division; the range 2700 yards. Standing up and pointing their rifles over the hedge they blazed away very steadily at the dervishes. Occasionally they caught and slew a group, but at that period it was difficult to make out, even through good field-glasses, whether the infantry fire was really effective. There was no doubt about what the gunners were doing, for horses and riders and footmen were bowled over or sank to the ground as shrapnel and common shell struck their ranks. The artillerymen invariably trained their weapons to bear upon the front of the densest of the dervish columns, seeking to pulverise them. As for the Maxims—and I closely watched the effect of their fire through my glasses—I am compelled to say that they often failed to settle upon the swarming foe. At any rate, their effectiveness was not equal to what might have been expected. Would the Khalifa succeed, in the face of such an awful cannonade, in reaching the zereba with a corporal’s guard? But after all, it usually takes tons of iron and lead to kill a man. There was marvellous vitality in the dervish masses. Thousands were knocked over by the screaming, bursting shells, which made hills and plain ring with thunderous uproar. But numbers of the apparently killed were merely wounded, and they speedily rose and truculently hastened forward anew with their fellow-tribesmen. A diversion that told momentarily in the enemy’s favour occurred. The extreme dervish right at that moment appeared climbing the slopes of Jebel Surgham. Emir Melik’s wing, hidden from view by that intervening high ground, had, as it came on, been reinforced by a part of Yacoub’s division. By other accounts Osman Digna, as well, had united forces with Melik. There suddenly sprang into threatening proximity before us, a force of at least fifteen odd thousand men, with a wide surf-line of white, red, and gold lettered banners, less than a mile away. Brandishing their weapons and shouting “Allah!” down the slopes they ran towards the zereba. Emirs rode in front, and gaunt, black riflemen sped like hounds, keeping pace with the horses. The guns of one battery, then another, and finally all three, upon General Lyttelton’s left, were turned upon them. Maxims also were swung round, and the long-distance volleys were dropped for shorter ranges. The dervish main columns which had got shelter in low khors re-appeared, and without pause joined in the hot rush for our zereba. Our elated foemen evidently thought they would at last be able to close with us. In their ignorance they reckoned not with the accuracy and discipline of the British infantry fire. Nor had they then learned to dread the terrible bullets of our men’s Lee-Metford rifles. Later in the day, as well as on the following one, I heard many expressions of regret from wounded and unwounded dervishes that they were so mad as to charge the white soldiers, whose bullets rarely missed. The light was good, the hour about 7 a.m., and the ranges shifted rapidly from 1700 yards to 1500 yards, 1200 yards down to 1000 yards. Guns, Maxims, and rifles were blazing in fullest fury at the enemy, as, in their heroic effort, they sought to charge home upon us. From wing to wing Gatacre’s division was firing sharply, a blaze of flame, section volleys and independently. The Grenadier Guardsmen’s shooting was noted as conspicuously steady and deadly effective. Except the two companies of the Rifles on the left, who, owing to the nature of the ground on their front, could do little, the British infantry were hotly occupied. Rifles became too warm to be held, and were in some cases changed for those of rear-rank men’s. In one or two instances the reserves closed up, to give every soldier an opportunity of being actually engaged. They took the place of sections in the firing lines, whilst their comrades fell back and refilled their cartridge pouches. The Lancers sent forward a dismounted squadron or two which filled the gap between the zereba and the Nile, whilst the gunboats “Melik” and “Sultan” moved in and took part in that stage of the battle. And still the dervishes got nearer, swinging up their left, for their right was now fairly held by the British fire. Colonels Maxwell’s and Lewis’s brigades had to address themselves to the task of checking the Khalifa’s attack. Colonel Long had so disposed the cannon and Maxims that the guns rendered invaluable help. At that period the main body of the dervishes moved forward more carefully, taking cover and evidently watching the issue of Yacoub’s and Wad Melik’s assaulting columns.

The army of white flags, led by Yacoub and Wad Melik, exhibited dash, courage, and persistence. Never was a column of men so hammered and mutilated and probably so surprised. They were torn and thrown about as puppets before the hurricane of shell fire, and laid in windrows like cut grain before the hail of the Lee-Metfords. Twelve hundred short yards away, Surgham’s bare slopes were being literally covered with corpses and writhing wounded. In sheer blundering brutishness, the ferocious dervishes tried to stem the storm. Wave followed wave of men, they surged together, inviting greater disaster, but always striving to get nearer us. Their front had covered the whole slopes of Jebel Surgham and their left overlapped part of the Khalifa’s right. Death was reaping a gigantic harvest. Hecatombs of slain were being spread everywhere in front. The fight was terrible, the slaughter dreadful. So far we had scarcely suffered loss, only a few of the enemy’s riflemen having paused and thought of firing at us. Muskets they had discharged in the air, after their manner, when advancing from their encampment. But that is one of their customs, employed to work up a proper warlike ardour. Viewed from our side, it had been so far the least dangerous battle ever soldier bore part in. For five, ten minutes, less or more—the drama being enacted was too fearful and fascinating for one to take note of time—Yacoub and his legions still strove to breast the whirlwind of destruction involving them. Battered, torn, rent into groups, the survivors at length began to move off rapidly across our front, to their left. As yet there was no running away, they were but changing direction and massing at another point. With, if possible, swifter, deadlier fire they were followed and driven. Maxims, Lee-Metfords, and Martini-Henrys from Maxwell’s brigade shattered the loose and weakened dervish columns. The few rounds fired back at us by the enemy from their Krupp gun and rifled cannon, which were stationed near the Khalifa’s banner during the first part of the action, did no harm. In fact, their shells burst two or three hundred yards short of the zereba. At first they were mistaken for badly-aimed shells fired by the gunboats, from which a few pitched near us, or by the batteries upon our left. For a moment the Sirdar was wroth at what was fancied to be our gunners’ blundering practice. It was quickly discovered, however, that the particular shells in question were aimed by the dervishes. Very soon,—whether settled by our guns, our Maxims, or by infantry volleys, I know not,—the dervish cannon and their foolish efforts to shell our lines troubled us no more. We knew afterwards that they had also got one of their 5-barrelled Nordenfeldts to work for a while. Nobody in our ranks, I think, was actually aware of the fact at the time, so indifferent was the aiming and so bad the handling of the gun.

Still, the crucial stage of the first action was not over. The Sheikh Ed Din had driven the Egyptian cavalry and Camel Corps from Um Mutragan, inflicting loss upon them and getting temporary possession of several guns of the horse battery. He was following them up vigorously, and the Camel Corps, protected by the gunboats’ fire, was seeking shelter near the river and close to the north end of the zereba, where it luckily succeeded in getting. It was after seven a.m., and Colonel Broadwood’s troopers were trying to shake off flanking parties of the enemy as they rode to the north, towards our previous camp. Our batteries were still pounding the Khalifa’s main body, which had got to within 1400 yards of the south-western angle of the zereba. Wavering, and driven before the murderous tornado of exploding bombs and pitiless lead, they too swung round and made for cover beyond range, flying towards the west and slightly to the rear. Yacoub and Melik followed the black flag in the same direction, and the dervish left wing edged off to Um Mutragan. They had come, first of all, direct, as if intending to assault the western angles of the zereba. Then Yacoub and Melik had led them to the right, so that they covered Surgham and came on in front of the British division. Blindly they had stumbled into the impassable fire from the south face of our lines and ultimately relinquishing the task had hastened, as I have stated, across our front towards their main body. The guns and Maxims withal of Wauchope’s and Maxwell’s infantry, must have weakened the hope in the Khalifa’s breast of closing with us. Although the range was longer, the central columns had been subjected to almost as destructive a cannonading as the dervishes on Surgham’s slopes got. So far it had been a gunner’s day, and to the artillery in the preliminary stages, if not—with one exception—in the later, belonged the full honours of the fight. At length with one mind, banner-bearers and all, swiftly the dervish columns, remaining intact, faced to the left, and moved behind the western hills. There was a pause, a respite for some minutes, which their jehadieh and others left upon the field of battle profited by to crawl upon their stomachs to within 800 yards less or more of the zereba, and open a sharp rifle fire upon us. Volley firing and shell firing dislodged many of them, but others kept potting away, increasing our casualty returns, particularly in the 1st, or Wauchope’s brigade. Just then the battle broke out with greater fury than ever. What happened in the dervish army may be guessed.

Out of immediate danger and re-formed, the Khalifa and Yacoub determined upon a second attack. With a rush like a mountain torrent three columns spouted from shallow ravines, and at a break-neck run came forward. Part of Wad Melik’s men uprose from the west sides of Surgham, the Khalifa and Yacoub came upon us from the south-west, and a smaller body from the west. In half delirium and full frenzy on rushed the dervishes. Our guns, knowing the range to a nicety—for they were able to see landmarks put down the day before—hurled at them avalanches of shell. The vivid air blazed and shook, and the hail of Lee-Metfords cut, like mighty scythes, lanes in the columns massed ten-deep. Greater resolution and bravery no men ever possessed. In face of destruction and death they continued their wild race. But they were thinning or being thinned as they drew nearer. When about 1100 yards away a body of horsemen, two hundred or so, the Khalifa’s own tribesmen, Taaisha Baggara, chiefs and Emirs, setting spurs to their horses charged direct for the zereba. Cannon and Maxims smashed them, infantry bullets beat against and pierced through them. At every stride their numbers diminished, horses and riders being literally blown over or cut and thrown down. Undaunted a remnant held on to within two or three hundred yards of Colonel Maxwell’s line, where the last of the gallant foemen tumbled and bit the dust. Partly encouraged by the self-sacrificing devotion of the horsemen, the footmen followed. The black flag was carried to within 900 yards of Colonel Maxwell’s left. Learning from their earlier failure, the Khalifa’s men directed their attack upon the Egyptian troops. But the British division’s cross-fire smote them, and the guns and Maxims knocked all cohesion out of their ranks. Still defiantly they set their standards and died around them. Then I noted there were again signs of wavering amongst the main body, who were hanging back. The big black flag was stuck in a heap of stones, and the more devoted sought to rally there. Abdullah himself and his chiefs endeavoured to collect the broken columns. It was attempted in the face of a bombardment that would have shaken a city, and a fusilade that ought to have mown down every blade of halfa-grass near. But Maxwell’s men seemed not quite to get the range. The flag and flagstaff were riddled with bullet holes, and the dead were being piled around. Still, dervish after dervish sprang to uphold the black banner of Mahdism. A herculean black grasped the staff in one hand, and leaned negligently against it for what appeared to be the space of five or ten minutes,—probably less than one minute,—ere the soldiers managed to give him his final quietus. Then it was that the remnant of the army of the Khalifa began to melt away. It was more than human nature could bear. The dense columns had shrunk to companies, the companies to driblets, which finally fled westward to the hills, leaving the field white with jibbeh-clad corpses like a landscape dotted with snowdrifts.

It was about eight o’clock, and the first action was virtually over and won. Good fortune, as the Sirdar admitted, had in many respects attended him. With a trifling loss of a few hundred men he had discomfited and slain 10,000 of the great dervish army. Presumably, Abdullah had lost the flower of his brave and devoted troops. There were yet a thousand or more of Jehadieh lying about under cover potting at the zereba. Many of them shammed being wounded to get closer to us. Sharp volleys and more shell-fire duly disposed of those determined snipers. It was from that source, during the critical stages of the battle when the infantry were stopping the Khalifa’s columns, that our chief casualties occurred. Some of these sharpshooters crept to within 800 yards of the British lines, and up to 400 yards from Maxwell’s. It was from them that Captain Caldecott received his death-wound and the Cameron losses came. I could not but observe the fact, as I walked and rode about behind the firing lines during the action. Still, the battle of Omdurman has the right to be considered from the victor’s point of view the safest action ever fought. The Warwick loss in the first action was one officer killed and two men wounded; the Camerons, one man killed and two officers and eighteen men wounded—Colonel Money had two horses shot under him, as at the Atbara; the Seaforths had eighteen men wounded; and the Lincolns ten men wounded. In General Lyttelton’s brigade the Grenadier Guards had one officer, Captain Bagshot, and four men wounded; the Northumberland Fusiliers had but one man wounded; the Lancashire Fusiliers four men wounded; and the Rifles six men wounded.