Editor’s Note: The following is extracted from Famous Sea Fights from Salamis to Tsu-Shima, by John Richard Hale (published 1911). All spelling in the original.

In the American Civil War there had been no battle between ironclad fleets. “Monitors” had engaged batteries. The Merrimac had had her duel with the first of the little turret-ships. But experts were still wondering what would happen when fleets of armoured ships, built in first-class dockyards, met in battle on the sea.

The war between Austria and Italy in 1866 gave the first answer. The experiment was not a completely satisfactory one, and some of its lessons were misread. Others were soon made obsolete by new developments in naval armaments.

Still, Lissa will always count among the famous sea-fights of the world, for it was the first conflict in which the armoured sea-going ship took a leading part. But there is another reason: it proved in the most startling way—though neither for the first time nor the last—that men count for more than machines, that courage and enterprise can reverse in the actual fight the conditions that beforehand would seem to make defeat inevitable. “Give me plenty of iron in the men, and I don’t mind so much about iron in the ships,” was a pithy saying of the American Admiral Farragut. There was iron enough in the Austrian sailors, Tegethoff and Petz, to outweigh all the iron in the guns and armour of the Italian admirals, Persano and Albini, and the “iron in the men” gave victory to the fleet that on paper was doomed to destruction.

At the present time, when in our morning papers and in the monthly reviews we find such frequent comparisons between the fleets of the Powers, comparisons almost invariably based only on questions of ships, armour, guns, and horse-power, and leaving the all-important human factor out of account, it will be interesting to compare the relative strength—on paper—of the Austrian and Italian fleets in 1866, before telling the story of Lissa.

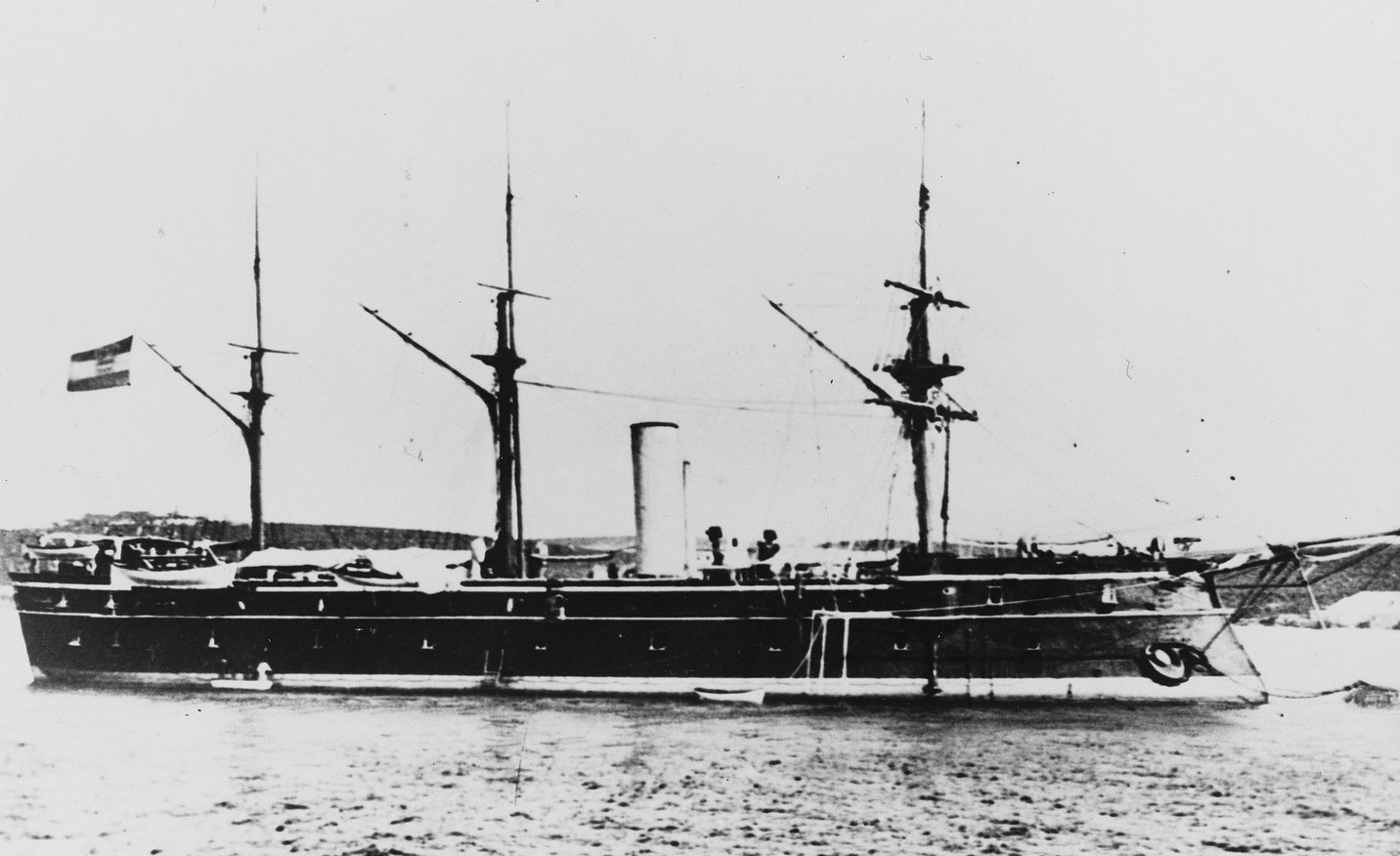

Austria had only seven ironclads. All were of the earlier type of armour-clad ships, modelled on the lines of the old steam frigates, built of wood, and plated with thin armour. The two largest—ships of 5000 tons and 800 horse-power—mounted a battery of eighteen 48-pounder smooth bores. They had not a single rifled gun in their weak broadsides. These were the Ferdinand Max and the Hapsburg. The Kaiser Max, the Prinz Eugen, and Don Juan de Austria were smaller ships of 3500 tons and 650 horse-power, but they had a slightly better armament, sixteen smooth-bore muzzle-loading 48-pounders, and fourteen rifled guns, light breech-loading 24-pounders. The Salamander and the Drache were ships of 3000 tons and 500 horse-power. They mounted sixteen rifled 24-pounders and ten smooth-bore 48-pounders. These five smaller ironclads were the only ships under the Austrian flag at all up to date. There were an old wooden screw line-of-battle ship and four wooden frigates, but these had neither rifled guns nor armour, and the naval critics of the day would doubtless refuse to take them into account. Then there were some wooden unarmoured gunboats and dispatch vessels.

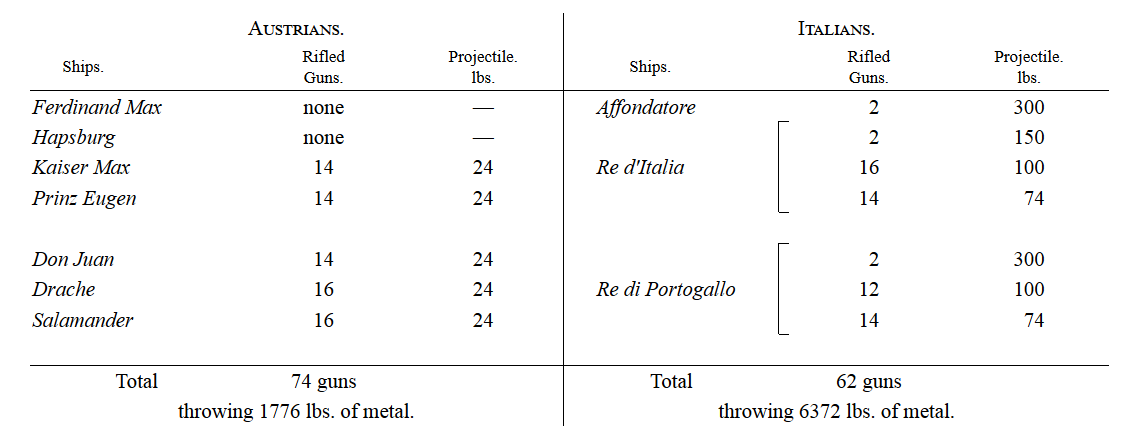

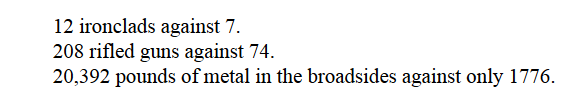

Now turning to the Italian Navy List, we find that these six ironclads, two of them without a single rifled gun, would have to face no less than twelve armoured ships, every one of them carrying rifled guns. One of them was a thoroughly up-to-date vessel, just commissioned from Armstrong’s yard at Elswick, the armoured turret-ram Affondatore (i.e. “The Sinker”). A correspondent of The Times saw her when she put into Cherbourg on the way down Channel. He reported that she looked formidable enough to sink the whole Austrian ironclad fleet single-handed. She was a ship of 4000 tons and 750 horse-power, iron-built, heavily armoured, and with a spur-bow for ramming. She carried in her turret two 10-inch rifled Armstrong guns, throwing an armour-piercing shell of 295 pounds—say 300-pounders, and let us remember the heaviest rifled gun in the Austrian fleet was the little 24-pounder. Then there were two wooden ironclads of 5700 tons and 800 horse-power, the Re d’Italia and the Re di Portogallo. The Re di Portogallo carried 28 rifled guns, two 300-pounders, twelve 100-pounders, and fourteen 74-pounders. The Re d’Italia mounted thirty-two rifled guns, two 150-pounders, sixteen 100-pounders, fourteen 74-pounders, and besides these four smooth-bore 50-pounders. On paper these three ships, the two “Kings”and the Affondatore, ought to have blown the Austrian ironclads out of the sea or sent them to the bottom. Let us compare the number of rifled guns and the weight of metal. There is no need to count the smooth-bores, for the Merrimac-Monitor fight had proved how little they could do even against weak armour. Here is the balance-sheet:—

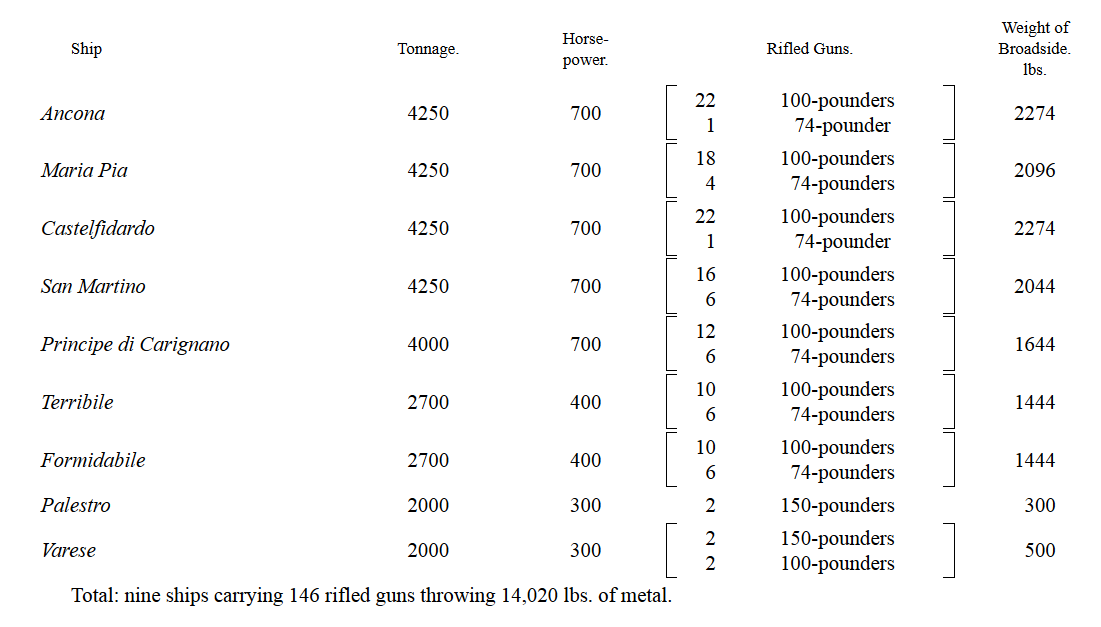

Even the Affondatore was supposed to be what the Dreadnought is to older ships in these paper estimates. What would she be with the two “Kings” helping her? But this was not all; the Italians could place in line nine more ironclads. Here is this further list:—

What could the seven Austrian ironclads with their 74 little guns throwing 1776 pounds of metal do against these nine ships with double the number of guns and nearly ten times the weight of metal in their broadsides? But add in the three capital ships before noted on the Italian side, and we have:—

Clearly it would be mad folly for the Austrian fleet to challenge a conflict! It would be swept from the Adriatic at the first encounter!

Here, then, are our calculations as to the command of the Adriatic at the outset of the war of 1866. They leave out of account only one element—the men, and the spirit of the men. Let us see how the grim realities of war can give the lie to paper estimates.

Wilhelm von Tegethoff, who commanded the Austrian fleet with the rank of rear-admiral, was one of the world’s great sailors, and the man for the emergency. He had as a young officer taken part in the blockade of Venice during the revolution of 1848 and 1849; he had seen something of the naval operations in the Black Sea during the Crimean War, as the commander of a small Austrian steamer, and during the war of 1864 he had commanded the wooden steam frigate Schwarzenberg in the fight with the Danes off Heligoland. Besides these war services he had taken part in an exploring expedition in the Red Sea and Somaliland, and he had made more than one voyage as staff-captain to the Archduke Maximilian, whose favourite officer and close friend he had been for years. When the Archduke, an enthusiastic sailor, resigned his command of the Austrian fleet to embark for Mexico, where a short-lived reign as Emperor and a tragic death awaited him, he told his brother, the Emperor Francis Joseph, that Tegethoff was the hope of the Austrian navy.

The young admiral (he was not yet forty years of age) had concentrated his fleet at Pola, the Austrian naval port near Trieste. He had got together every available ship, not only the seven ironclads, but the old line-of-battle ship and the wooden frigates and gunboats. The Admiralty at Vienna had suggested that he should take only the ironclads to sea, but he had replied: “Give me every ship you have. You may depend on my finding some good use for them.” He believed in his officers and men, and relied on them to make a good fight on board anything that would float, whether the naval experts considered it was out of date or not. Among his officers he had plenty of men who were worthy of their chief and inspired with his own dauntless spirit, and the crews were largely composed of excellent material, men from the wilderness of creek and island that extends along the Illyrian and Dalmatian shores, fishermen and coasting sailors, many of them so lately joined that instead of uniform they still wore their picturesque native costume. The crew looked a motley lot, but, to use Farragut’s phrase, “there was iron in the men.”

Twenty-seven ships in all, small and large, were moored in four lines in the roadstead of Fasana, near Pola. But they did not remain idly at their anchors. Every day some of them ran out to sea, to fire at moving targets or to practise rapid turning and ramming floating rafts. The bows were strengthened by cross timbers in all the larger ships, and in the target work the crews were taught to concentrate the fire of several guns on one spot. But Tegethoff knew he had not a single gun in his fleet that could pierce the armour of the Italian vessels. He told his officers that for decisive results they must trust to the ram. He had painted his ships a dead black. The Italian colour was grey. “When we get into the fight,” said Tegethoff, “you must ram away at anything you see painted grey.”

War was declared on 20 June. Tegethoff had been training his fleet since 9 May, and was ready for action. He at once sent out the Stadion (a passenger steamer of the Austrian Lloyd line, employed as a scout and armed with two 12-pounders) to reconnoitre the Italian coast of the Adriatic. The Stadion returned on the 23rd with news that though war had been expected for weeks the Italian fleet was not yet concentrated. A few of the ships were at Ancona, but the greater part of it was reported to be at Taranto, with Admiral Count Persano, the commander-in-chief, who from the first displayed the strangest irresolution.

Tegethoff was anxious to attempt to engage the division at Ancona before it was joined by the main body from Taranto, but he was held back by orders from his Government directing him to remain in the Northern Adriatic covering Venice. It was not till 26 June that he obtained a free hand within limits defined by an order not to go further south than the fortified island of Lissa.

He left Pola that evening with six ironclads, the wooden frigate Schwarzenberg, five gunboats, and the scouting steamer Stadion. He had hoisted his rear-admiral’s flag on the Erzherzog Ferdinand Max. He made for Ancona, and was off the port at dawn next day. The first shots of the naval war were fired in the grey of the morning, when three of the Austrian gunboats chased the Italian dispatch vessel Esploratore into the port, outside of which she had been on the look-out. The Austrians were able clearly to see and count the warships under the batteries in the harbour. Besides other craft, there were eleven of Persano’s twelve ironclads, the squadron from Taranto having reached Ancona the day before. Only the much-vaunted Affondatore had not yet joined.

Tegethoff cleared for action, and steamed up and down for some hours, just beyond the range of the coast batteries. It was a challenge to the Italians to come out and fight. But Persano did not accept it. He afterwards made excuses to his Government, saying he had not yet completed the final fitting out of his ships. The moral effect on both fleets was important. The Austrians felt an increased confidence in their daring leader and a growing contempt for their adversaries. On the 24th the Austrian army, under the Archduke Albert, had beaten the Italians at Custozza, and the Austrian navy looked forward to the same good fortune. The Italians were depressed both by the news of Custozza and the hesitation of their admiral to risk anything.

Early in the day Tegethoff started on his return voyage to Fasana, where he arrived in the evening, and found the ironclad Hapsburg waiting to join his flag, after having been refitted in the dockyard of Pola. As there were now persistent rumours that the Italians were going to attempt an attack on Venice, Tegethoff remained in the Fasana roadstead, continuing the training of his fleet. On 6 July he again took it to sea, practised fleet manœuvres under steam, and showed himself in sight of Ancona. But the Italian fleet was still lying idly in the harbour, and Tegethoff once more returned to Fasana in the hope that Persano would attempt some enterprise, during which he would be able to fall upon him in the open.

The Italian admiral was meanwhile wasting time in lengthy correspondence with his Government, and sending it letters which revealed his irresolution and incompetence so plainly that they ought to have led to his immediate supersession. He complained he had not definite orders, though he had been directed to destroy the Austrian fleet, if it put to sea, or blockade it, if it remained in harbour. He explained now that he was mounting better guns in some of his ships, now that he was waiting for the Affondatore to join. Once he actually wrote saying that some new ironclads ought to be purchased from other powers to reinforce him. At last he was plainly told that if he did not at once do something for the honour of the Italian navy he would be relieved of his command. With the Austrians victorious in Northern Italy, a raid on Venice would have been too serious an operation, but he proposed as an alternative that a small land force should be embarked for a descent on the fortified island of Lissa, on the Dalmatian coast. His fleet would escort it, and co-operate by bombarding the island batteries. The plan was accepted, and he proceeded to execute it.

It was about as bad a scheme as could be imagined. It is a recognized principle of war that over-sea expeditions should only be undertaken when the enemy’s fleet has been either rendered helpless by a crushing defeat or blockaded in its ports. Before sending the transports to Lissa Persano should have steamed across to Pola and blockaded Tegethoff, fighting him if he came out. But Persano had a delusive hope that he could perhaps score a victory without encountering the Austrian fleet by swooping down on Lissa, crushing the batteries with a heavy bombardment, landing the troops, hoisting the Italian flag, and getting back to his safe anchorage at Ancona before Tegethoff could receive news of what was happening, and come out and force on a battle.

Lissa was defended by a garrison of 1800 men, under Colonel Urs de Margina. This small body of troops held a number of forts and batteries mounting eighty-eight guns, none of them of large calibre. The works were old, and had been hurriedly repaired. Most of them dated from the time of the English occupation of the island during the Napoleonic wars. Persano expected that Lissa would be a very easy nut to crack.

On 16 July the Italian fleet sailed from Ancona. Even now Persano carried out his operations with leisurely deliberation. On the 17th he reconnoitred Lissa, approaching in his flagship under French colours. Early on the 18th the fleet closed in upon the island, flying French colours, till it was in position before the batteries.

The commandant had cable communication with Pola by a line running by Lesina to the mainland. He reported to Tegethoff the appearance of the disguised fleet, and then the opening of the attack on his batteries. At first the Austrian admiral could hardly believe that the Italians had committed themselves to such an ill-judged enterprise, and thought that the attack on Lissa might be only a feint meant to draw his fleet away from the Northern Adriatic, and leave an opening for a dash at Pola, Trieste, or Venice itself. But cablegrams describing the progress of the attack convinced him it was meant to be pressed home, and he telegraphed to Colonel de Margina, telling him to hold out to the last extremity, and promising to come to his relief with all the fleet. This message did not reach the colonel, for just before it was dispatched an Italian ship had cut the cable between Lissa and Lesina, and seized the telegraph office of the latter island. Tegethoff’s message thus fell into Persano’s hands. He persuaded himself that it was mere bluff, intended to encourage the commandant of Lissa to hold out as long as possible. He thought Tegethoff would remain in the Northern Adriatic to protect or to overawe Venice.

The attempt to reduce the batteries of Lissa by bombardment during the 18th proved a failure. In the evening Persano was in a very anxious state of mind. He had made no arrangements for colliers to supply his fleet, and his coal was getting low. It was just possible that Tegethoff might come out and force him to fight, and he thought of returning to Ancona. But if he did he would be dismissed from his command. At last he made up his mind to land the troops next morning, and try to carry the forts by an assault combined with an attack from the sea. His second in command, Admiral Albini, with the squadron of wooden ships and gunboats that accompanied the ironclads, was directed to superintend and assist in the landing of the troops. They were to be embarked in all available boats, and to land at 9 a.m. During the night the ram Affondatore joined the fleet, and Persano had all his twelve ironclads before Lissa.

On the morning of the 18th the sea was smooth, and covered with a hot haze that limited the view. The soldiers were being got into the boats, and the ships were steaming to their stations for the attack, when about eight o’clock the Esploratore, which had been sent off to scout to the north-westward, appeared steaming fast out of a bank of haze with a signal flying, which was presently read, “Suspicious-looking ships in sight.” Tegethoff was coming.

He had left Fasana late on the afternoon of the 18th, with every available ship, large and small, new and old, wooden wall and ironclad. He would find work for all of them. All night he had steamed for Lissa, anxious at the sudden cessation of the cable messages, but still hoping that he would see the Austrian flag flying on its forts, or if not, that he would at least find the enemy’s fleet still in its waters.

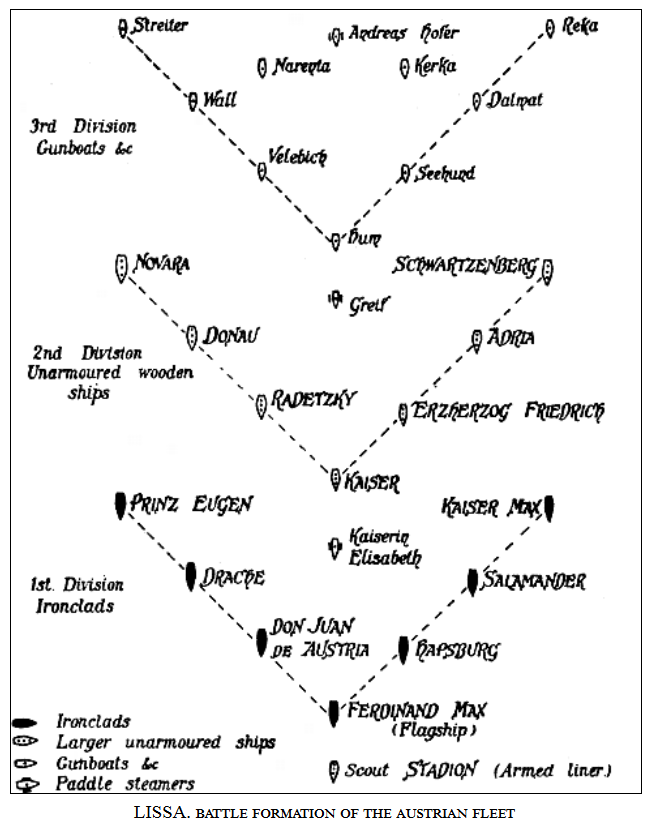

He had organized his fleet in three divisions. The first under his own personal command was formed of the seven ironclads. The second division, under Commodore von Petz, was composed of wooden unarmoured ships. The commodore’s flag flew on the old steam line-of-battle ship Kaiser, a three-decker with ninety-two guns on her broadsides, all smooth-bores except a couple of rifled 24-pounders. With the Kaiser were five old wooden ships (Novara, Schwarzenberg, Donau, Adria, and Radetzky) and a screw corvette, the Erzherzog Friedrich. The third division, under Commandant Eberle, was composed of ten gunboats. A dispatch-boat was attached to each of the leading divisions, and the scout Stadion, the swiftest vessel in the fleet, was at the immediate disposal of the admiral, and was sent on in advance.

The fleet steamed during the night in the order of battle that Tegethoff had chosen. The divisions followed each other in succession, each in a wedge formation, the flagship of the division in the centre with the rest of the ships to port and starboard, not in line abreast, but each a little behind the other. The formation will be understood from the annexed diagram.

It was an anxious night for the Austrian admiral. For some hours there was bad weather. Driving showers of fine rain from a cloudy sky made it difficult at times to see the lights of the ships, and it was no easy matter for them to keep their stations. The sea was for a while so rough that the ironclads had to close their ports, and there was a danger that if the weather did not improve and the sea become smoother they would not be able to fight most of their guns. But Tegethoff held steadily on his course for Lissa. On sea, as on land, there are times in the crisis of a war when the highest prudence is to throw all ordinary rules of prudence aside, and take all risks.

The admiral had resolved from the outset that, whatever might be the result, the Austrian fleet should not lie in safety under the protection of shore batteries, leaving the Italian command of the Adriatic unchallenged. He felt that it would be better to sink in the open sea, in a hopeless fight against desperate odds, rather than ingloriously to survive the war, without making an effort to carry his flag to victory. So he steamed through the night, followed by his strange array of ships that another leader might well have considered as little better than useless encumbrances, and in front the handful of inferior ironclads that might well be regarded as equally doomed to destruction when they met the more numerous and more heavily armed ships of the enemy. But he had put away all thoughts of safety. He was staking every ship and every man and his own life against the faint chance of success. The coming day might see his fleet destroyed, but such a failure would be no disgrace. On the contrary, it would only be less honourable than a well-won victory, and would be an inspiration to the men of a future fleet that would carry the banner of the Hapsburgs in later days. So he rejoiced greatly when, as the day came, the weather began to clear, and the Stadion signalled back that Lissa was still holding out and the enemy’s fleet lay under its shores.

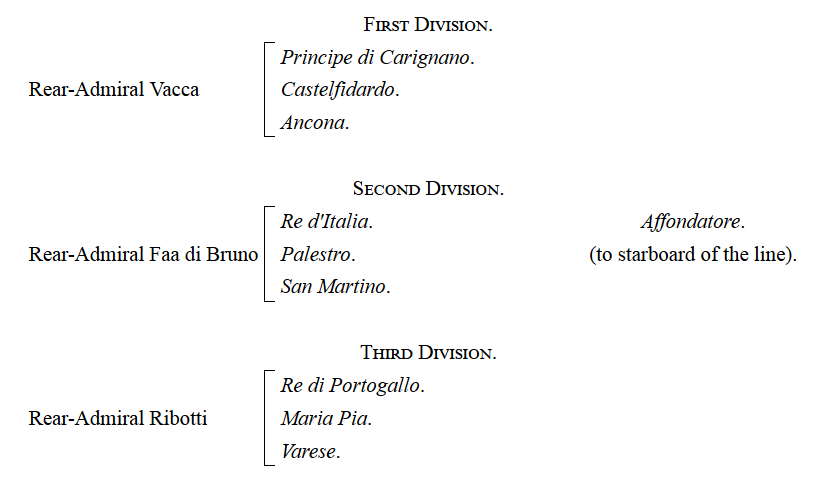

As soon as he read the Esploratore’s signal, Persano had no doubt that Tegethoff was upon him. He countermanded the attack on Lissa, ordered Albini to re-embark the troops, and proceeded to form his ironclads in line of battle, intending to engage the enemy with these only. The ironclads were standing in to attack the batteries of San Giorgio at the north-east end of the island. Persano formed nine of them in three divisions, which were to follow each other in line ahead, the ram Affondatore being out of the line and to starboard of the second division. The formation was as follows:—

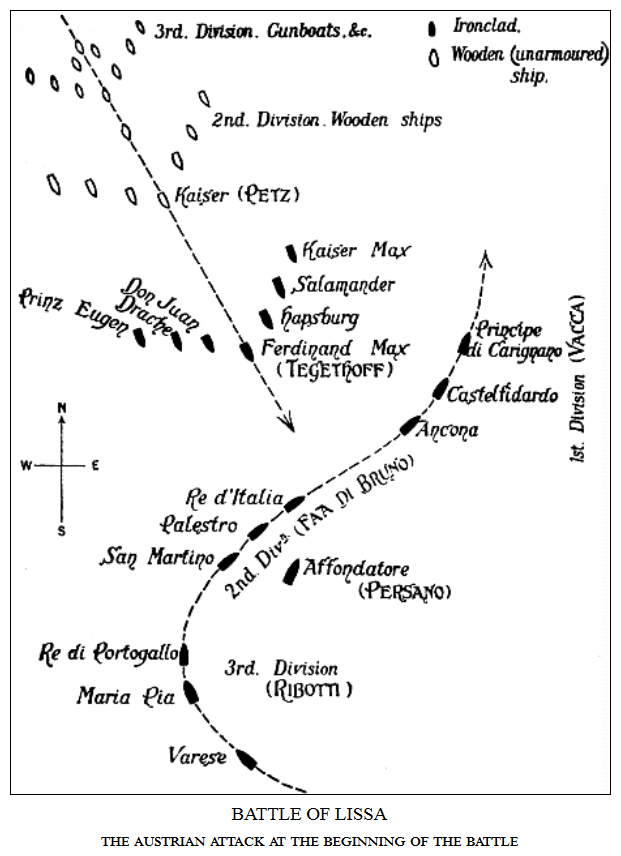

The two other Italian ironclads, the Formidabile and the Varese, were not in the line, and took no part in the coming battle. The Formidabile had suffered heavily in the attack on the shore batteries, numerous shells entering her port-holes and making a slaughterhouse of her gun-deck. She had been ordered to Ancona, and had left Lissa in the early morning. The Varese had been detached to assist in operations on the other side of the island, and joined Albini’s squadron of wooden ships while the fight was in progress. Persano’s battle line first steered west along the north side of Lissa. About ten o’clock the driving mist on the sea cleared, and the Austrian fleet was then seen approaching on a S.S.E. course. Persano altered his own course, and, led by Vacca in the Principe di Carignano, the Italian ironclads turned in succession on a N.N.E. course. Thus as the Austrians closed on them the fleet in a sinuous line was steering across the bows of the attacking ships.

It was at this moment that Persano changed his flag from the Re d’ Italia to the Affondatore, the former ship slowing down to enable the admiral to leave her, and thus producing a wide gap between Vacca’s and Faa di Bruno’s divisions. The result of this sudden change of flagship was confusing, as most of the Italian ships were unaware of it, and still looked to the Re d’ Italia for guidance, and did not notice signals made by the Affondatore.

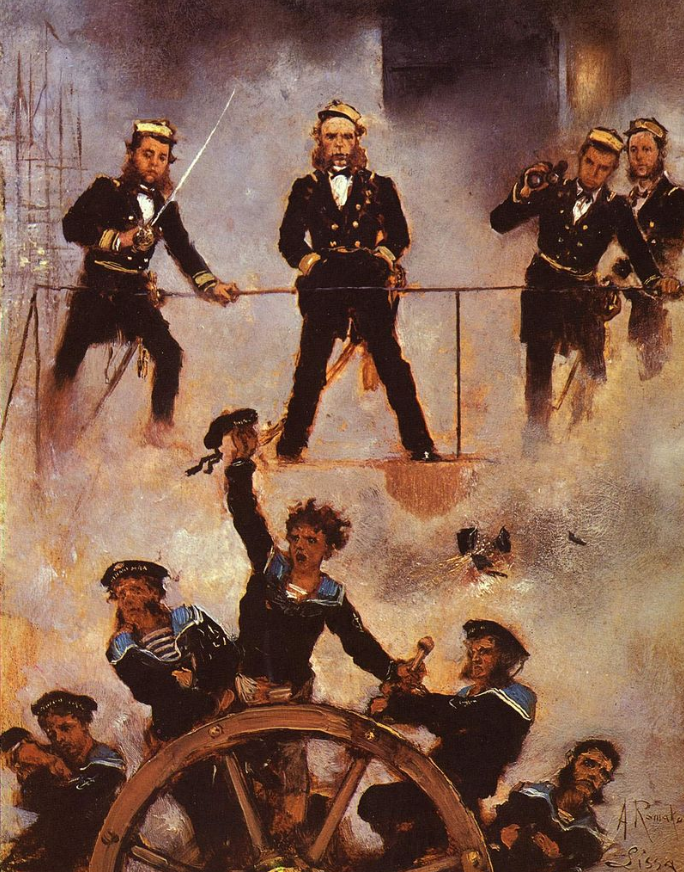

Tegethoff had given the successive signals as the mist dispersed, “Clear for action—Close order—Look-out ships return to their stations—Full speed ahead.” As the last of the fog disappeared and the sun shone out, he saw to his delight the Austrian flag still flying on the hill-side batteries of Lissa, and close in front between him and the island shores the enemy’s fleet crossing his bows. Out fluttered his battle signal, “Ironclads will ram and sink the enemy!” A final signal was being prepared, “Muss Sieg von Lissa werden!” (“There must be a victory of Lissa!”), but the close encounter had begun, and the ships were wrapped in clouds of powder-smoke before it could be hoisted.

While Persano was passing from the Re d’ Italia to the ram Affondatore, Vacca had begun the fight by firing his broadside at the advancing Austrians. The Castelfidardo and the Ancona followed his example. But Tegethoff held his fire, waiting for close quarters. One of these first shots killed Captain Moll of the Drache on the bridge of his ship. A young lieutenant took command of her. He was Weiprecht, who in later years became famous as the commander of the Austrian exploring ship Tegethoff in the Arctic regions.

As the fleets closed the Austrians opened fire, aiming, not at the armoured sides of the enemy, which no gun of theirs could penetrate, but at their port-holes and bridges. Tegethoff in his flagship the Ferdinand Max was looking for something to ram, but in the dense mass of smoke he passed through the wide gap between Vacca’s division and the Re d’Italia, then finding no enemy in his front, he turned and went back into the battle fog of the Italian centre. The three ironclads on his left (Hapsburg, Salamander, and Kaiser Max) were engaged with Vacca’s division, the van of the Italian fleet. The three others, Don Juan, Drache, and Prinz Eugen, had flung themselves on Faa di Bruno’s ships in the centre. Von Petz coming up with the wooden ships gallantly attacked Ribotti’s rearward division, any one of which should in theory have been able to dispose of his entire force. The gunboats hung on the margin of the fight, which had now become a confused mêlée. And while the Austrian wooden ships were thus risking themselves in close action, Albini’s Italian division of wooden ships looked on from a safe distance.

One can only tell some of the striking incidents of the battle, without being able even to fix the precise order of time in which they occurred. When the Merrimac sank the Cumberland with one blow of her ram in Hampton Roads, the Federal ship was at anchor. But even in the confusion and semi-darkness of the mêlée at Lissa it was found that it was not such an easy matter to ram a ship under way. The blow was generally eluded by a turn of the helm. Von Petz’s flagship, the old three-decker Kaiser, towering amid the battle-smoke, attracted the attention of Persano in the Affondatore, and seemed an easy victim for his ram. But the big ironclad was unhandy, and took eight minutes to turn a full circle, and twice Petz eluded her attack. The two 300-pounders of the Affondatore did much damage on board the Kaiser, but the wooden ship’s broadside swept the upper works of the ram as the two vessels passed each other, and strewed her deck with wreckage. The fire of the heavy rifled guns on the Italian ironclads did severe execution on the Austrian wooden ships. The captain of the Novara was killed; the Erzherzog Friedrich and the Schwarzenberg were badly hulled, and leaked so that they were only kept afloat by their steam pumps. The Adria was three times on fire. But Petz and the wooden division did good service by keeping the rearward Italian ships fully occupied.

Meanwhile Tegethoff, standing on the bridge of the Ferdinand Max, all reckless of the storm of fire that roared around him had dashed into the Italian centre. He rammed first the Re d’Italia, then the Palestro, but both ships evaded the full force of the blow, and the Austrian flagship scraped along their sides, bringing down a lot of gear. The mizzen-topmast and gaff of the Palestro came down with the shock, and the gaff fell across the Austrian’s deck, with the Italian tricolour flying from it. Before the ships could clear an Austrian sailor secured the flag. It would seem that the glancing blow given to the Re d’Italia had disorganized her steering gear, and for a while she was not under control. Two other ships joined the flagship in attacking her, all believing she was still Persano’s flagship. The Palestro, fighting beside her, was set on fire by shells passing through her unarmoured stern. The fire made such rapid progress that she drew out of the fight, her crew trying to save their ship.

Von Sterneck, the captain of the Ferdinand Max, had gone half-way up the mizzen-rigging, to look out over the smoke; he reported that the Re d’Italia was not under full control, and Tegethoff once more dashed at his enemy. The bow of the Ferdinand Max this time struck the Re d’Italia full amidships, and simply forced in her side, making an enormous gap, crushing and smashing plates and frames. As the Ferdinand Max reversed her engines and drew her bows out of her adversary’s side, the Re d’Italia heeled over and sank instantly, carrying hundreds to the bottom and strewing the surface with wreckage and struggling men.

The Austrians, after a moment of astonished horror at their own success, cheered wildly. The Ferdinand Max tried to save some of the drowning men, and was lowering her only boat that remained unshattered by the fire, when the Italian ironclad Ancona tried to ram her. The Austrian flagship evaded the blow, and the Ancona, as she slid past her, almost touching her gun-muzzles, fired a broadside into her. The powder-smoke from the Italian guns poured into the port-holes of the Ferdinand Max, and for a few moments smothered her gun-deck in fog, but it was a harmless broadside. In their undisciplined haste to fire the Italians had loaded only with the cartridge, there was not a shot in the guns. This tells something of the confusion on board.

Another Austrian ironclad and two of the gunboats made plucky efforts to save some of the survivors of the Re d’Italia, but they, too, were driven off by the fierce attacks of Italian ships.

Meanwhile Petz with his wooden ships had fought his way through the Italian rear. With his old three-decker he boldly rammed the Re di Portogallo. The Italian ship evaded the full force of the blow, but the tall wooden vessel scraped along her side, starting several of her armour plates, carrying away port-hole covers and davits, dragging two anchors from her bows, smashing gun-muzzles and jerking four light guns into the sea. But the Kaiser herself suffered from the close fire of the Re di Portogallo’s heavy guns and the shock of collision. Her stem and bowsprit were carried away, the gilded crown of her figure-head falling on her enemy’s deck. Her foremast came crashing down on her funnel, and wrecked it, and the mass of fallen spars, sails, and rigging was set on fire by sparks and flame from the damaged funnel, the collapse of which nearly stopped the draught of the furnaces and dangerously reduced the pressure on the boilers and the speed of the engines.

The Re di Portogallo sheered off, but her consort, the Maria Pia, came rushing down on the disabled Kaiser. Petz avoided her ram, and engaged her at close quarters, but the shells of the Maria Pia burst one of the Kaiser’s steam-pipes, temporarily disabled her steering gear, and did terrible execution in her stern battery. Petz himself was slightly wounded. With great difficulty he extricated his ship from the mêlée, and cutting away the wreckage, and fighting the fire that was raging forward, he steered for San Giorgio, the port of Lissa, to seek shelter under its batteries. His wooden frigates gallantly protected his retreat and escorted him to safety, then turned back to join once more in the fight. This was the moment when Albini with the Italian wooden squadron might easily have destroyed Petz’s division, but during the day all he did was to fire a few shots at a range so distant that they were harmless.

Persano, in the Affondatore, had for a moment threatened to attack the Kaiser, as she struggled out of the mêlée. He steamed towards her, and then suddenly turned away. He afterwards explained that, seeing the plight of Petz’s flagship, he thought she was already doomed to destruction, and looked upon it as useless cruelty to sink her with her crew.

The fleets were now separating, and the fire was slackening. In this last stage of the mêlée the Maria Pia and the San Martino collided amid the smoke, and the latter received serious injuries. As the fleets worked away from each other there was still a desultory fire kept up, but after having lasted for about an hour and a half the battle was nearly over.

Tegethoff, having got between the Italians and Lissa, reformed his fleet in three lines of divisions, each in line ahead, the ironclads to seaward nearest the enemy; the wooden frigates next; and the gunboats nearest the land. Every ship except the Kaiser (which lay in the entrance of the port) was still ready for action. Some of them were leaking badly, including his flagship, which had started several plates in the bow when she rammed and sank the Re d’Italia. The fleet steamed slowly out from the land on a north-easterly course, the ironclads firing a few long-ranging shots at the Italians.

Persano was also reforming his fleet in line, and was flying a signal to continue the action, but he showed no determined wish to close with Tegethoff again. On the contrary, while reforming the line he kept it on a northwesterly course, and thus the distance between the fleets was increasing every minute, as they were moving on divergent lines. Gradually the firing died away and the battle was over. Albini, with the wooden squadron, and the ironclad Terribile, which had remained with him, and taken no part in the fight, ran out and joined the main fleet.

Persano afterwards explained that he was waiting for Tegethoff to come out and attack him. But the Austrian admiral had attained his object, by forcing his way through the Italian line, and placing himself in a position to co-operate with the batteries of Lissa, in repelling any further attempt upon the island. There was no reason why, with his numerically inferior fleet, he should come out again to fight a second battle.

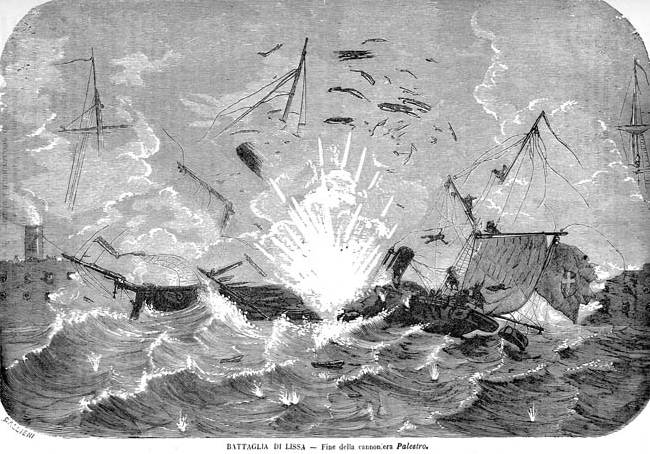

But though the action was ended, there was yet another disaster for the Italians. The Palestro had been for two hours fighting the fire lighted on board of her by the Austrian shells. Smoke was rising from hatchways and port-holes, but as she rejoined the fleet she signalled that the fire was being got under and the magazines had been drowned. Two of the smaller ships, the Governolo and the Independenza, came to her help and took off her wounded. To a suggestion that he should abandon his ship, her commander, Capellini, replied: “Those who wish may go, but I shall stay,” and his officers and men remained with him, and continued working to put out the fire. But the attempt to drown the magazines had been a failure, for suddenly a deafening explosion thundered over the sea, the spars of the Palestro were seen flying skyward in a volcano of flame. As the smoke of the explosion cleared, the heaving water strewn with debris showed where the ship had been.

The Austrian fleet was steaming into San Giorgio, amid the cheers of the garrison and the people, when the explosion of the Palestro took place. Persano drew off with his fleet into the channel between Lissa and the island of Busi, and when the sun went down the Italian ships were still in sight from the look-out stations on the hills of Lissa.

The Austrians worked all night repairing damages, and preparing for a possible renewal of the fight in the morning. But at sunrise the look-outs reported that there was not an Italian ship in sight. Persano had steered for Ancona after dark, and arrived there on the 21st.

He was so unwise as to report that he had won a great naval victory in a general engagement with the Austrians in the waters of Lissa. Italy, already smarting under the defeat of Custozza, went wild with rejoicing. Cities were illuminated, salutes were fired, there was a call for high honours for the victorious admiral. But within forty-eight hours the truth was known. It was impossible to conceal the fact that Lissa had been unsuccessfully attacked for two days, and that on the third it had been relieved by Tegethoff dashing through the Italian fleet, and destroying the Re d’Italia and the Palestro, without himself losing a single ship. There were riots in Florence, and the cry was now that Admiral Persano was a coward and a traitor. To add to the gloom of the moment the ram Affondatore, which had been injured in the battle, sank at her anchors when a sudden gale swept the roadstead of Ancona.

Three of the twelve Italian ironclads had thus been lost. Three more were unavailable while their damages were being slowly repaired. Peace was concluded shortly after, and the Italian navy had no opportunity of showing what it could do under a better commander.

In the sinking of the Re d’Italia some 450 men had been drowned. More than 200 lost their lives in the explosion of the Palestra, but the other losses of the Italians in the Battle of Lissa were slight, only 5 killed and 39 wounded. The Austrians lost 38 killed (including two captains) and 138 wounded. These losses were not severe, considering that several wooden ships had been exposed to heavy shell-fire at close quarters, and one must conclude that the gunnery of the Italian crews was wretched. The heaviest loss fell on Petz’s flagship, the Kaiser, which had 99 killed and wounded. Some of the gunboats, among which were some old paddle-ships, though they took part in the fighting, had not a single casualty.

Persano was tried by court-martial and deprived of his rank and dismissed from the navy. Tegethoff became the hero of Austria. His successful attack on a fleet that in theory should have been able to destroy every one of his ships in an hour, will remain for all time an honour to the Austrian navy, and a proof that skill and courage can hope to reverse the most desperate disadvantages.