Editor’s Note: The following is extracted from Famous Sea Fights from Salamis to Tsu-Shima, by John Richard Hale (published 1911). All spelling in the original.

At sunrise the armada streamed out of the Bay of Gomenizza, and sped southwards with oar and sail. The Gulf of Arta was passed, and the admirals were reminded not of the far-off battle that saw the flight of the Egyptian Queen and the epoch-making victory of Augustus Cæsar, but of a sea-fight in the same waters only a few years ago that had ended in dire disaster to the Christian arms. Then through the hours of darkness the fleet worked its way past the rock-bound shores of Santa Maura, whose cliffs glimmered in the moonlight. The roar of the breakers at their base warned the pilots to give them good sea room. In the grey of the morning the peaks and ridges of Ithaca and Cephalonia rose out of the haze upon the sea, and soon after sunrise the fleet was moving through the narrow strait between the islands.

In the strait there were shelter and smooth water, but the wind was rising, backing from north-west to west, and raising a sea outside Cephalonia that sent a heavy swell sweeping round its southern point and into the opening of the narrows. As the leading ships reached the mouth of the strait Don Juan did not like the look of the weather, and decided to anchor in the Bay of Phiscardo, a large opening in the Cephalonian shore just inside the strait.

For two days the fleet lay weather-bound in the bay. During one of these days of storm Kara Khodja, the Algerine, tried again to reconnoitre the fleet, but was driven off by the guardships at the entrance of the strait.

On 6 October the wind shifted to the east and the sea began to go down. Don Juan refused to wait any longer. The fleet put to sea, under bare masts, and, rowing hard against the wind and through rough water, it worked its way slowly across to the sheltered waters on the mainland coast between it and the islands of Curzolari. Here the fleet anchored for the night, just outside the opening of the Gulf of Corinth. Not twenty miles away up the gulf lay the Turkish fleet, for Ali had brought it out of the Bay of Lepanto, and anchored in the Bay of Calydon.

When the sun rose on the 7th, the wind was still contrary, blowing from the south-east. But at dawn the ships were under way, and moving slowly in long procession between the mainland and the islands that fringe the coast. There was a certain amount of straggling. It was difficult to keep the divisions closed up, and the tall galleasses especially felt the effect of the head wind, and some of the galleys had to assist them by towing.

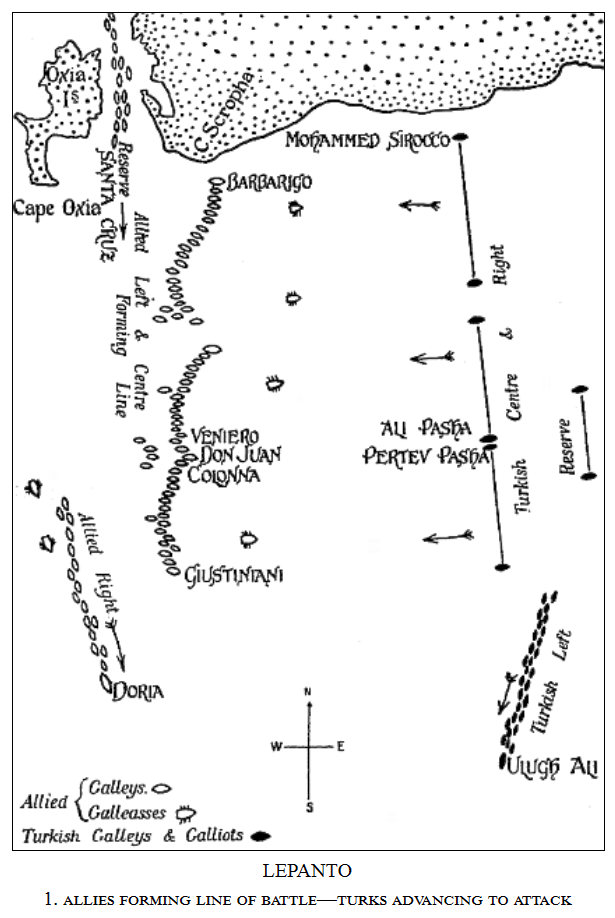

As the ships of the vanguard began to clear the channel between Oxia Island and Cape Scropha, and the wide expanse of water at the entrance of the Gulf of Corinth opened before them, the look-outs reported several ships hull down on the horizon to the eastward, the sun shining on their white sails, that showed like flecks of cloud on the sea-line.

The signal was sent back, “Enemy in sight,” for the number of sails told it must be a fleet, and could be none other than that of Ali Pasha. The allied squadrons began to clear for action, and Don Juan displayed for the first time the consecrated banner sent him by Pius V, a large square flag embroidered with the crucifix and the figures of Saints Peter and Paul.

It was an anxious time for the Christian admiral. His fleet, now straggling for miles along the coast, had to close up, issue from the channel, round Cape Scropha, and form in battle array in the open water to the eastward. If the Turks, who had the wind to help them, came up before this complex operation was completed, he risked being beaten in detail.

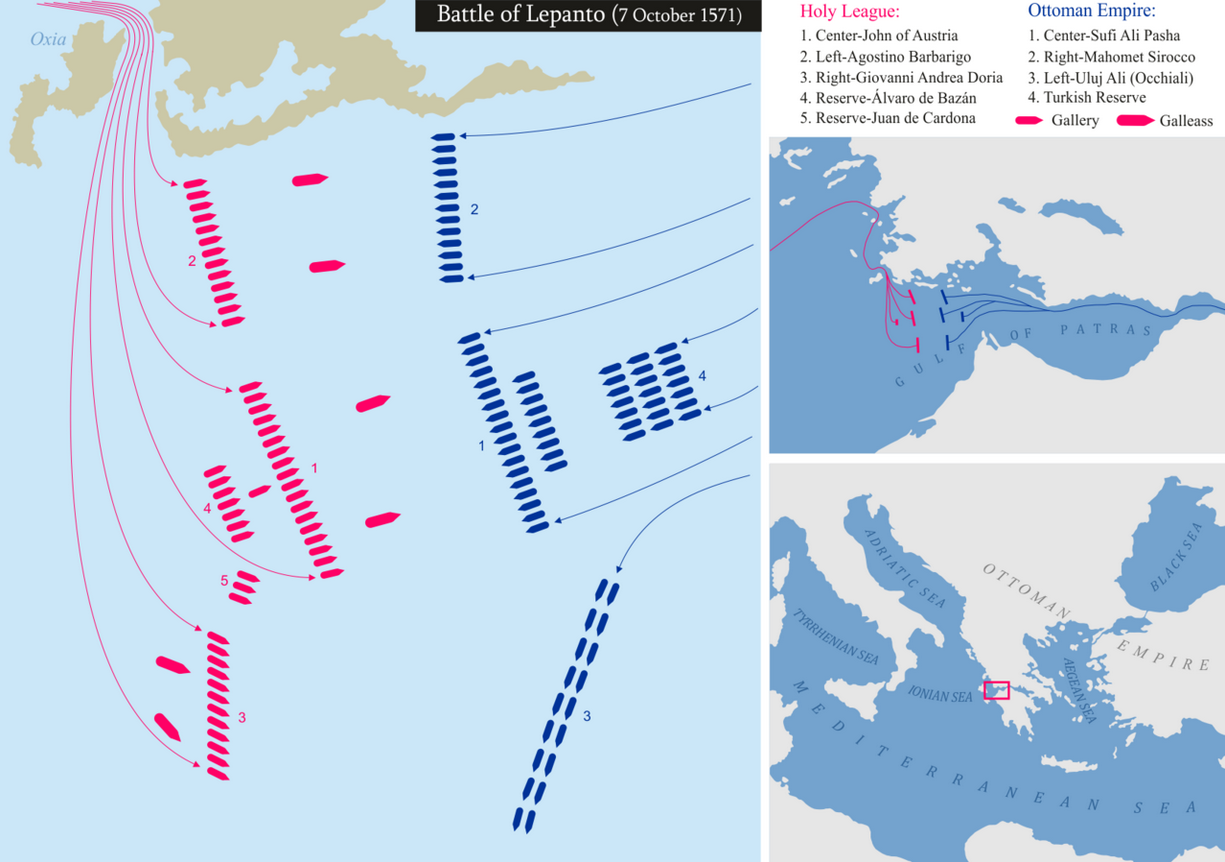

While the fleet was still working its way through the channel, Don Juan had sent one of the Roman pilots, Cecco Pisani forward in a swift galley to reconnoitre. Pisani landed on Oxia, climbed one of its crags, and from this lofty outlook counted 250 sail in the enemy’s fleet, which was coming out along the north shore of the gulf, the three main squadrons abreast, the reserve astern of them. Returning to the “Reale,” the pilot gave a guarded report to Don Juan, fearing to discourage the young commander now that battle was inevitable, but to his own admiral, the veteran Colonna, he spoke freely. “Signor,” he said, “you must put out all your claws, for it will be a hard fight.”

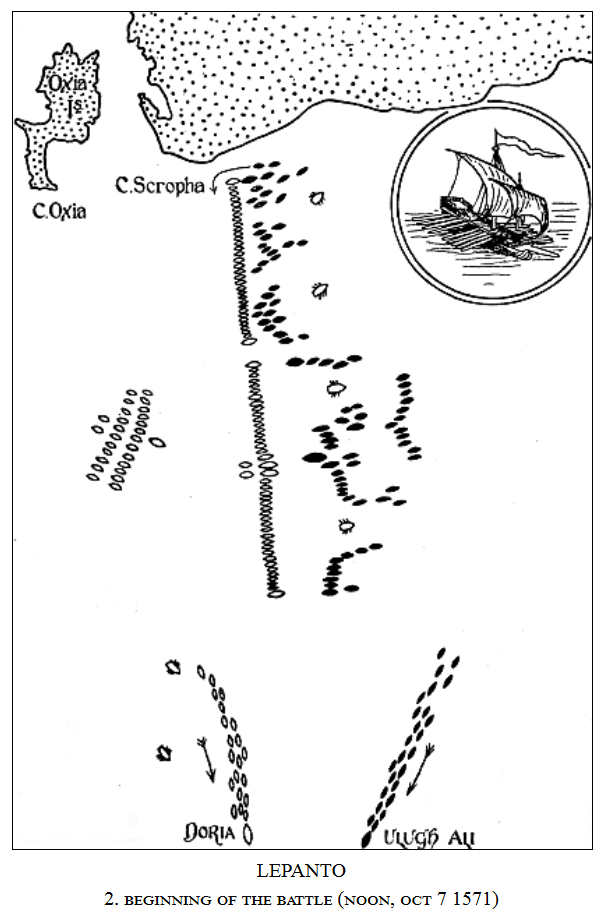

Then the wind suddenly fell and the sea became calm as a lake. The Turks were seen to be furling their now useless sails. The rapidity with which the manœuvre was simultaneously executed by hundreds of ships excited the admiration of the Christians. It showed the enemy had well-disciplined and practised crews. But at the same time the fact that at a crisis, when every moment gained was priceless, the Turks had lost the fair wind, convinced the allies that Heaven was aiding them, and gave them confidence in the promises of their chaplains, grey-cowled Franciscans and black-robed Dominicans, who were telling them that the prayers of Christendom would assure them a victory. Their young chief, Don Juan, left the “Reale” and embarked in a swift brigantine, in which he rowed along the forming line of the fleet. Clad in complete armour he stood in the bow holding up a crucifix, and as he passed each galley he called on officers and men to spare no effort in the holy cause for which they were about to fight. Then he returned to his post on the poop of the “Reale,” which was in the centre of the line, with several other large galleys grouped around her. As each ship was pulled into her fighting position, the Christian galley-slaves were freed from the oar and given weapons with which to fight for the common cause and their own freedom.

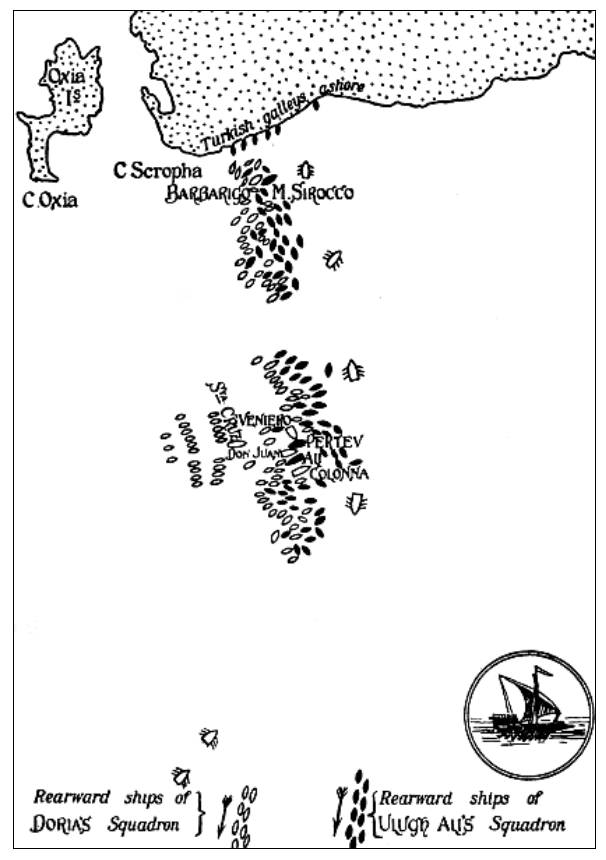

It was intended that the galleys of the left, centre, and right should form one long line, with the six galleasses well out in front of them, two before each division. These were to break the force of the Turkish onset with their cannon. But when the long line of the enemy’s galleys came rushing to the onset, Don Juan’s battle array was still incomplete. Barbarigo’s flagship was on the extreme left under the land. His division had formed upon this mark, “dressing by the left,” as a soldier would say. The tall galleasses of two gallant brothers, the Venetians Ambrogio and Antonio Bragadino, kinsmen of the hero of Famagusta, lay well out in front of the left division. All the ships had their sails furled and the long yards hauled fore and aft. Don Juan had formed up the centre division, two more galleasses out in front, the “Reale” in the middle of the line, the galleys of Veniero and Colonna to right and left, and two selected galleys lying astern, covering the intervals between them and the flagship. Only a few oars were being used to keep the ships in their stations. So far so good, but the rest of the allied fleet was still coming up. The reserve was only issuing from the channel behind Cape Scropha, and Doria was leading the right division into line, with his two galleasses working up astern, where their artillery would be useless. Thus when the battle began not much more than half of the Christian armada was actually in line. But for the sudden calm the position would have been even worse.

It was almost noon when the battle began. The first shots were fired by the four galleasses, as the long line of Ottoman galleys came sweeping on into range of their guns. Heavy cannon, such as they carried, were still something of a novelty in naval war, and the Turks had a dread of these tall floating castles that bristled with guns, from which fire, smoke, and iron were now hurled against them. One of the first shots crashed into the deck of Ali Pasha’s flagship, scattering destruction as it came. The Turkish line swayed and lost its even array. Some ships hesitated, others crowded together in order to pass clear of the galleasses. Daring captains, who ventured to approach with an idea of boarding them, shrank back under the storm of musketry that burst from their lofty bulwarks. The Turkish fleet surged past the galleasses, broken into confused masses of ships, with wide intervals between each squadron, as a stream is divided by the piles of a bridge.

This disarray of the Turkish attack diminished the fire their bow-guns could bring to bear on the Christian line, for the leading galleys masked the batteries of those that followed. Along the allied left and centre, lying in even array bows to the attack, the guns roared out in a heavy cannonade. But then as the Ottoman bows came rushing through the smoke, and the fleets closed on each other, the guns of the galleys were silent. For a few moments the fight had been like a modern battle, with hundreds of guns thundering over the sea. Now it was a fight like Salamis or Actium, except for the sharp reports of musketry in the mêlée and the cannon of the galleasses making the Turkish galleys their mark when they could fire into the mass without danger to their friends.

The first to meet in close conflict were Barbarigo’s division on the allied left and Mohammed Scirocco’s squadron, which was opposed to it on the Turkish right. The Egyptian Pasha brought his own galley into action on the extreme flank bow to bow with the Venetian flagship, and some of the lighter Turkish galleys, by working through the shallows between Barbarigo and the land, were able to fall on the rear of the extreme left of the line, while the larger galleys pressed the attack in front. The Venetian flagship was rushed by a boarding-party of Janissaries, and her decks cleared as far as the mainmast. Barbarigo, fighting with his visor open, was mortally wounded with an arrow in his face, and was carried below. But his nephew Contarini restored the fight, and with the help of reinforcements from the next galley drove the boarders from the decks of the flagship. Contarini was mortally wounded in the midst of his success. But two of his comrades, Nani and Porcia, led a rush of Venetians and Spaniards on to Mohammed Scirocco’s flagship, whose decks were swept by the fire of the arquebusiers before the charge of swords and pikes burst over her bows. The onset was irresistible. The Turks were cut down, stabbed, hurled overboard, Mohammed himself being killed in the mêlée.

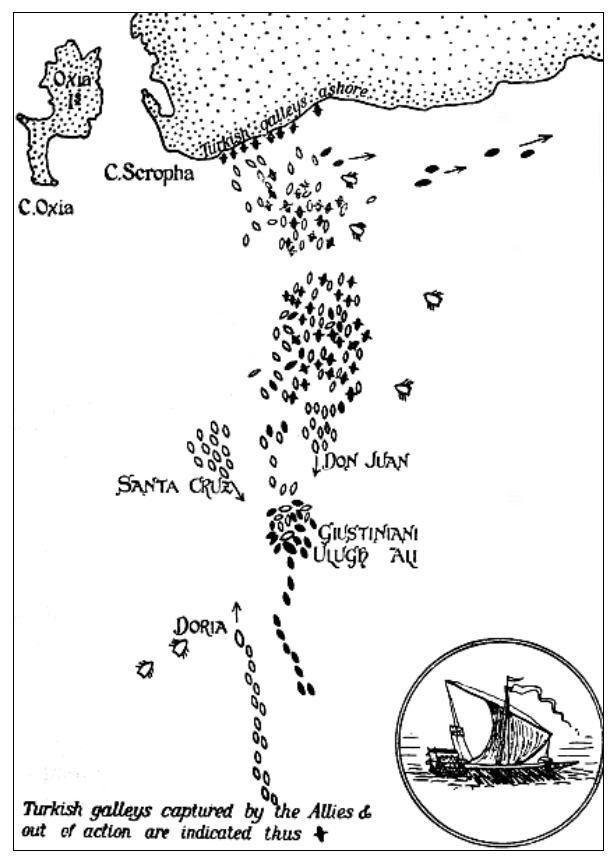

By the time the great galley of Alexandria was thus captured the landward wings of the two fleets were mingled together in a confused fight, in which there was little left of the original order. There was more trace of a line on the allied or Christian side. The Turks had not broken through them, but they had swung round, somewhat forcing Mohammed’s galleys towards the shore. When the standard of the Egyptian admiral was hauled down by the victorious Venetians, and the rowers suddenly ceased to be slaves and fraternized with the conquerors, some of the captains on the Turkish right lost heart, drove their galleys aground in the shallows and deserted them for the shore, where they hoped to find refuge among friends. On Don Juan’s left, though the fighting continued in a fierce mêlée of ships locked together, and with crews doing wild work with loud arquebuse and clashing sword, the battle was practically won.

Meanwhile there had been close and deadly fighting in the centre. The main squadron of the Turks had, like their right division, suffered from the fire of the advanced galleasses. Several shots had struck the huge galley that flew the flag of the Capitan-Pasha, Ali, a white pennon sent from Mecca, embroidered in gold with verses of the Koran. Ali steered straight for the centre of the Christian line, where the group of large galleys, the “Reale” with the embroidered standard of the Holy League, Colonna’s ship with its ensign of the Papal Keys, and Veniero’s with the Lion-flag of St. Mark, told him he was striking at the heart of the confederacy. He chose Don Juan’s “Reale” for his adversary, relying on the Seraskier Pertev Pasha, and the Pasha of Mitylene on his left and right, to support him by attacking the other two flagships.

Ali held the fire of his bow-guns till he was within a short musket-shot of his enemy, and then fired at point-blank. One of his cannon-balls crashed through the bow barrier of the “Reale,” and raked the rowers’ benches, killing several oarsmen. As the guns of the “Reale” thundered out their reply, the bow of the Turkish flagship, towering over the forecastle of Don Juan’s vessel, came through the smoke-cloud and struck the Spanish ship stem to stem with a grinding crash and a splintering of timber, throwing down many of the crew. The Turkish bow dug deep into the Spanish ship, and in the confusion of the collision it was thought for a moment she was sinking, but a forward bulkhead kept her afloat. Ali’s ship rebounded from the shock, then glided alongside the “Reale” with much mutual smashing of oars. The two ships grappled, and the hand-to-hand fight began. At the same time Pertev Pasha grappled Veniero’s flagship, and another Turkish galley, commanded by Ali’s two sons, forced its way through the line and engaged the two galleys that lay astern of the flagship. Then the Pasha of Mitylene closed upon Colonna’s ship, and all along the centre the galleys came dashing together. The crash of broken oars, the rattling explosions of arquebuses and grenades, the war-notes of the Christian trumpets and the Turkish drums, the clash of swords, the shouts and yells of the combatants, rose in a deafening din. Froissart wrote in an earlier day that sea-fights were always murderous. This last great battle of the medieval navies had the character of its predecessors. In this fight at close quarters on the narrow space afforded by the galleys’ decks there was no question of surrender on either side, no thought but of which could strike the hardest and kill the most. Nor could men, striving hand to hand in the confusion of the floating mêlée, know anything of what was being done beyond their limited range of view, so that even the admirals became for the moment only leaders of small groups of fighting-men. On the poop and forecastle of the “Reale” were gathered men whose names recalled all that was greatest in the annals of Spanish chivalry, veterans who had fought the Moor and voyaged the western ocean, and young cavaliers eager to show themselves worthy sons of the lines of Guzman and Mendoza, Benavides and Salazar. Don Juan, arrayed in complete steel, stood by the flagstaff of the consecrated standard. Along the bulwarks four hundred Castilian arquebusiers in corselet and head-piece represented the pick of the yet unconquered Spanish infantry. The three hundred rowers had left the oars, and, armed with pike and sword, were ready to second them, when the musketry ceased and the storming of the Turkish galleys began. From Ali’s ship a hundred archers and three hundred musketeers of the Janissary corps replied to the fire of the Spaniards. The range was a few feet. Men were firing in each other’s faces, and at such close quarters the arquebuse with its heavy ball was a more death-dealing weapon than the modern rifle. Such slaughter could not last, and the caballeros were eager to end it by closing on the Turks with cold steel.

Twice they dashed through the smoke over Ali’s bulwarks, and for a while gained a footing on the deck of the enemy’s flagship. Twice they were driven back by the reinforcements that Ali drew from the crews of galleys that had crowded to his aid. Then the Turks came clambering over the bows of the “Reale,” and nearly cleared the forecastle. Don Bernardino de Cardenas brought up a reserve from the waist of the ship and attacked the Turkish boarders in the bows. He was struck by a musket-ball. It dinted his steel helmet, but failed to penetrate. Cardenas fell, stunned by the shock of the blow, and died next day, “though he showed no sign of a wound.”

Don Juan himself was going forward sword in hand to assist in the fight in the bows of the “Reale,” and Ali was hurrying up reinforcements to the attack. It was a critical moment. But Colonna just then struck a decisive blow. He had boarded and stormed the ship that attacked him, a long galley commanded by the Bey of Negropont. Having thus disposed of his immediate adversary, he saw the peril of the “Reale.” Manning all his oars, he drove the bow of his flagship deep into the stern of Ali’s ship, swept her decks with a volley of musketry, and sent a storming-party on to her poop. The diversion saved the “Reale.” The Spaniards hustled the Turks over her bows at point of pike, and Ali, attacked on two sides, had now to fight on the defensive.

On the other side of the “Reale” Veniero’s flagship was making a splendid fight. It is the details of those old battles that bring home to us the changes of three centuries. A modern admiral stands sheltered in his conning tower, amid voice tubes and electrical transmitters. Veniero, a veteran of seventy years, stood by the poop-rail of his galley, thinking less of commanding than of doing his own share of the killing. Balls and arrows whistled around him, along the bulwarks amidships his men were fighting hand to hand with the Seraskier’s galley that lay lashed alongside. There were no orders to give for the moment, so he occupied himself with firing a blunderbuss into the crowd on the Turkish deck, and handing it to a servant to reload with half a dozen balls, and then firing again and again.

Here, too, in the main squadron were fighting the galleys of Spinola of Genoa, of the young Duke of Urbino, of the Prince of Parma, of Bonelli, the nephew of Pius V, of Sforza of Milan, and Gonzaga of Solferino, and the young heirs of the Roman houses of Colonna and Orsini. Venice had not all the glory of Lepanto. All Italy still remembers that every noble family, every famous city, from the Alps to Sicily, had its part in the battle.

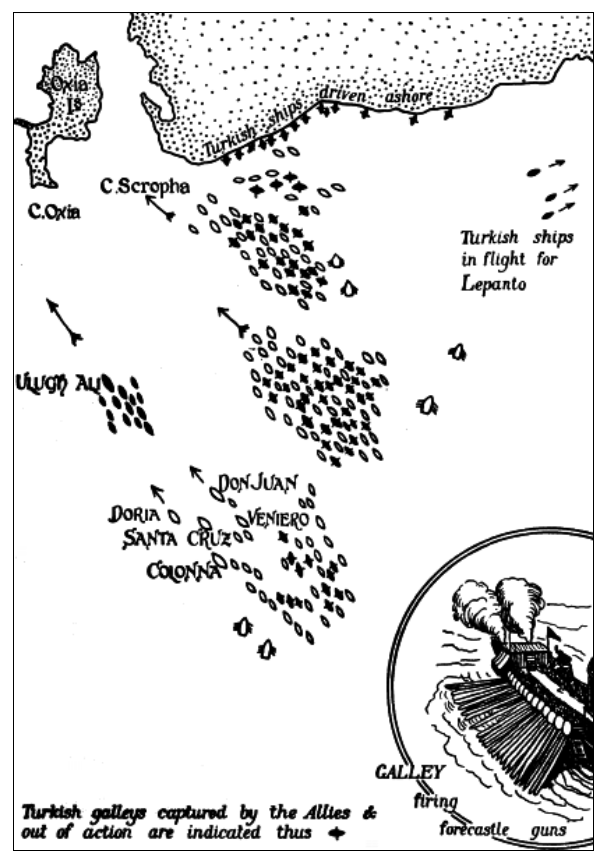

Colonna’s timely aid to the “Reale” was the turning-point of the fight in the centre. Led by Vasquez Coronada and Gil d’Andrada, the Spanish infantry poured into Ali’s ship, and winning their way foot by foot cleared her decks. Not one of her four hundred fighting-men survived. Ali himself was one of the last to fall. One account says that when all was lost he cut his throat with his dagger, another that he was shot down at close quarters. His head was cut off, placed on a pike, and carried to Don Juan with the captured standard of Mecca. The chivalrous young admiral turned with disgust from the sight of the blood-dripping head, and ordered it to be thrown into the sea.

The battle had lasted an hour and a half. Don Juan saw in the capture of the enemy’s flagship the assurance of victory. Like all great commanders, he knew the value of moral effect. He hoisted the consecrated banner of the League at the tall mast-head of the conquered galley, and bade his trumpeters blow a flourish and his men shout victory. In the confusion and uproar of the mêlée not many of the ships would see what was happening round the “Reale,” but this demonstration would attract the attention of friends and foes in the centre of the fight. It was just one of the moments when, both parties becoming exhausted by the prolonged struggle, success would belong to the side that could put forth even for a while the more vigorous effort, and the sight of the papal standard fluttering from the Turkish mast, instead of the banner of Mecca, inspired this effort on the part of the Christians, and depressed and discouraged their adversaries.

Pertev Pasha had lost heavily under the fire of the Venetian flagship, and had failed in an effort to board her. He cut his galley adrift. Veniero let her go, and turned to attack other enemies. Pertev’s ship drifted down on two Christian galleys, and was promptly boarded and taken. The Seraskier slipped on board of a small craft he was towing astern, reached another ship, and, giving up all hope of victory, fled with her from the fight. Veniero had meanwhile rammed and sunk two other galleys. He was wounded with a bullet in the leg, but he had the wound bandaged and remained on deck. The old man gave Venice good reason to be proud of her admiral.

Along the left and centre of the Christian armada there was now victory. Admirals and captains were busy storming or sinking such of the enemy’s ships as still maintained the fight. On the left Barbarigo had been mortally wounded, and the losses had been heavy, but the success was so pronounced that large numbers of men had been landed to hunt down the Turkish fugitives on the shore. In the centre there was still some hard fighting. Here it was that Miguel Cervantes, leading the stormers to the capture of a Turkish galley, received three wounds, one of which cost him his left hand.

When the battle began at noon, first on the allied left, then in the centre, Doria, the Genoese admiral who commanded the right, was not yet in position. His orders were to mark with his flagship the extreme right of the line of battle so that the rest of his division could form on this point. But it was soon seen that he was keeping away, steering southward into the open sea, with his division trailing after him in a long line, the galleasses that should have been out in front coming slowly up behind the squadron. Ulugh Ali with the left wing of the Turkish fleet had also altered his course, and was steering on a parallel line to that taken by the Genoese. Some of the Christian captains who watched these movements from the right centre thought that Doria was deserting the armada, and even that he was in flight, pursued by Ulugh Ali.

Doria afterwards explained that, as he steered out from behind the centre to take up his position in the battle line, he saw that Ulugh Ali, instead of forming on Ali Pasha’s flank, was working out to seaward, and he therefore believed that the Algerine was trying to get upon the flank of the allied line, in order to envelop it and attack from both front and rear, so as to crush the extreme right with a local superiority of force. His plan was, therefore, to confine himself to observing Ulugh Ali’s movements, steering on a parallel course in the hope of eventually closing and meeting him fairly ship to ship. Doria was an old sailor, perhaps the most experienced leader in the fleet, except the veteran Veniero. If he had been less of a tactician, perhaps he would have come into action sooner. And it is strange that, while playing for position against Ulugh Ali, he did not realize that if, instead of continually increasing his own distance from the centre, he had at any moment turned back towards it, he could thus force the Algerine admiral either to close with him or leave him free to overwhelm the Turkish main squadron by enveloping its left.

It was Ulugh Ali, not Doria, who turned back and ventured on a stroke like this. The Algerine had, after all, outmanœuvred the over-clever Genoese. The course taken by the two squadrons had, with the drift of the current, placed Ulugh Ali’s rearmost ships actually somewhat nearer the seaward flank of the main fighting lines than Doria’s galleys, which his squadron also outnumbered. A signal ran down the long line of the Turkish left, and while some of the galleys turned and bore down on Doria’s division, the rest swung round and, before Doria had quite realized what was happening, Ulugh Ali, with the heaviest ships of his division, was rushing towards the fight in the centre.

The brunt of the Algerine’s onset fell upon a dozen galleys on Don Juan’s right flank. The furthest out, the flagship of the Knights of Malta, was attacked by seven of the enemy’s vessels. Next to her lay the papal galley “Fiorenza,” the Piedmontese “Margarita di Savoia,” and seven or eight Venetian ships. All these were enveloped in the Turkish attack which engaged the line in front, flank and rear. There were no enemies the Algerines hated so fiercely as the Knights of Malta, but, even though they had the flagship of the Order at such a fearful disadvantage, they did not venture to close with it until they had overwhelmed the knights and their crew with a murderous fire of bullets and arrows at close quarters. Then they boarded the ship and disposed of the few surviving defenders. The commander, Giustiniani, wounded by five arrows, and a Sicilian and a Spanish knight alone survived, and these only because they were left for dead among the heaps of slain that encumbered the deck. Ulugh Ali secured as a trophy of his success the standard of the Knights. In the same way the “Fiorenza” and the “San Giovanni” of the papal squadron, and the Piedmontese ship, were rushed in rapid succession. On the “Fiorenza” the only survivors were her captain, Tomasso de Medici, and sixteen men, all wounded; the captain of the “San Giovanni” was killed with most of his men, and the captain of the Savoyard ship survived an equally terrible slaughter, after receiving no less than eleven wounds.

But Ulugh Ali was not to be allowed to “eat up” the line ship by ship. Reinforcements were now arriving in rapid succession. First Santa Cruz, with the reserve, dashed into the fight, and though twice wounded with shot from a Turkish arquebuse, drove his flagship into the midst of the Algerines. Don Juan cut adrift a captured ship he had just taken in tow, and with twelve galleys hastened to assist the reserve in restoring the fight. Doria, leaving part of his division to encounter the galleys Ulugh Ali had detached against it, led the rest into the mêlée. Colonna and Veniero were supporting Don Juan. The local advantage of numbers, which Ulugh Ali at first possessed, soon disappeared, but for more than an hour the fight continued with heavy loss on both sides. Then the Algerine admiral struggled out of the mêlée, and with fourteen ships fled north-westward, steering for Cape Oxia and the wide channel between Ithaca and the mainland. Santa Cruz and Doria pursued for a while, but a wind sprang up from the south-east, and the fugitives set their long lateen sails. Under sail and oar a corsair could generally defy pursuit.

The pursuers gave up the chase and returned to where Don Juan and the other admirals were securing their prizes, clearing the decks of dead, collecting the wounded, and hurriedly repairing damages. It was now after four o’clock, and less than three hours of daylight remained for these operations. Besides the handful that had escaped with Ulugh Ali, a few galleys had got away into the Gulf of Corinth, making for Lepanto, but the great Turkish armada had been destroyed, and the victorious armament was mistress of the Mediterranean.

The success had been dearly bought. On both sides the losses in the hard-fought battle had been terrible. The allies had about 7500 men killed or drowned, two-thirds of these fighting-men, the rest rowers. The nobles and knights had exposed themselves freely in the mêlée, and Spain, Malta, Venice, and the Italian cities had each and all their roll of heroic dead. The list of the Venetians begins with the names of seventeen captains of ships, including the admiral Barbarigo, besides twelve other chiefs of great houses who fought under the standard of St. Mark in command of companies of fighting-men. No less than sixty of the Knights of St. John “gave their lives that day for the cause of Christ,” to quote the annalist of the Order. Several others were wounded, and of these the Prior Giustiniani and his captain, Naro, of Syracuse, died soon after. One of the knights killed in the battle was a Frenchman, Raymond de Loubière, a Provençal. Another Frenchman, the veteran De Romegas, fought beside Don Juan on the “Reale,” and to his counsel and aid the commander-in-chief attributed much of his success in the campaign. The long lists of the Spanish, Neapolitan, Roman, and Genoese nobles who fell at Lepanto include many historic names.

The losses of the defeated Moslems were still heavier. The lowest estimate makes the number of the dead 20,000, the highest 30,000. Ali Pasha and most of his captains were killed. Ali’s two sons and several of his best officers were among the prisoners. Fifteen Turkish galleys were sunk or burned, no less than 190 ships were the prizes of the victors. A few galleys had escaped by the Little Dardanelles to Lepanto. A dozen more had found refuge with Ulugh Ali in the fortified harbour of Santa Maura. The Algerine eventually reached Constantinople, and laid at the feet of Sultan Selim the standard of the Knights of Malta, which he had secured when he was in temporary possession of Giustiniani’s flagship.

Don Juan’s best trophies of victory were the 12,000 Christian slaves found on board the captured galleys. They were men of all nations, and some of them had for years toiled at the oar. Freed from their bondage, they carried throughout all Christendom the news of the victory and the fame of their deliverer.

Hardly three hours of daylight remained when the battle ended, and the Christian admirals reluctantly abandoned the pursuit of Ulugh Ali. The breeze that had aided the Algerine in his flight was rapidly increasing to a gale, and the sea was rising fast. The Christian fleet, encumbered with nearly two hundred prizes, and crippled by the loss of thousands of oars shattered in the fight, was in serious danger in the exposed waters that had been the scene of the battle. By strenuous and well-directed efforts the crews of oarsmen were hurriedly reorganized. Happily the wind was favourable for a run through the Oxia Channel to the Bay of Petala. The prizes were taken in tow. Sails were set. Weary men tugged at the oar, knights and nobles taking their places among them. As the October night deepened into darkness, amid driving rain and roaring wind-squalls, the fleet anchored in the sheltered bay.

The gale that swept the Adriatic was a warning that the season for active operations was drawing to a close, and the admirals reluctantly decided that no more could be done till next spring. The swiftest ships were sent off to carry the good news of Lepanto to Rome and Messina, Venice and Genoa, Naples and Barcelona. The fleet returned in triumph to Messina, and entered the port trailing the captured Turkish standards in the water astern of the ships that had taken them, while pealing bells and saluting cannon greeted the victors.

Lepanto worthily closed the long history of the oar-driven navies. The galleasses, with their tall masts and great sails, and their bristling batteries of cannon, which lay in front of Don Juan’s battle line, represented the new type of ship that was soon to alter the whole aspect of naval war. So quickly came the change that men who had fought at Lepanto were present, only seventeen years later, at another world-famed battle that was fought under sail, the defeat of King Philip’s “Grand Armada” in the Narrow Seas of the North.