Editor’s note: The following account of a battle in the War of 1812 is extracted from Our Country, Volume 2, by Benson J. Lossing (published 1877). All spelling in the original.

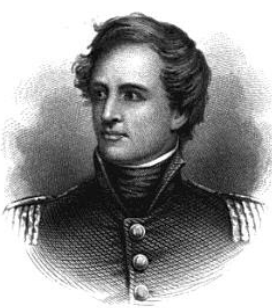

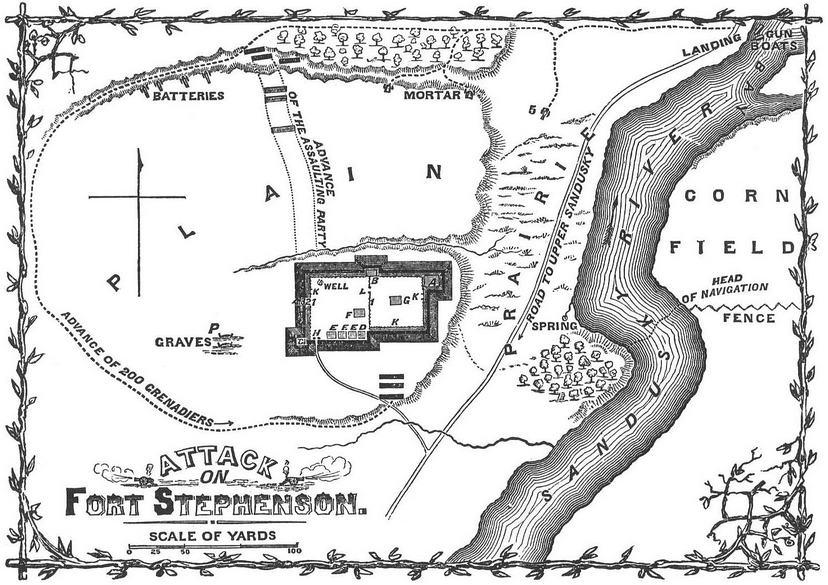

We left General Harrison and his little army at Fort Meigs. When he was assured that Proctor and his allies had returned to Fort Malden, he left General Clay in command of Fort Meigs, and proceeded to Lower Sandusky (now Fremont, on the west bank of the Sandusky River) and the interior, to make preparations for the defence of the Erie Frontier against the foiled and exasperated foe. He met Governor Meigs at Lower Sandusky, with a considerable body of Ohio militia, pressing forward to his relief; and he found the Ohio settlements so full of enthusiasm, that he felt sure of aid whenever he might call for it. Meanwhile Tecumtha had been urging Proctor to renew the siege of Fort Meigs. That timid General hesitated a long time; but finally, late in July, he appeared before Fort Meigs with his Indian allies – his own and Tecumtha’s followers numbering about four thousand. The tribes of the northwest were fully represented. Satisfied that he could not capture the fort, Proctor and his white troops embarked with their stores, on the 28th of July, for Sandusky Bay, with the intention of attacking Fort Stephenson, at Lower Sandusky, a regular earthwork, with a ditch, circumvallating pickets, bastions, and block-houses. It was garrisoned by one hundred and sixty men under the command of Major George Croghan of the regular army, and then only twenty-one years of age.

Proctor’s dusky allies marched across the country to assist in the siege; and when, on the afternoon of the 31st, the British in transports and gun-boats appeared at a turn in the river a mile from the fort, it was perceived that the woods near by were swarming with Indians. Tecumtha had concealed about two thousand of them in the forest, to watch the roads along which reinforcements might attempt to reach Fort Stephenson. Proctor at once made a demand for the surrender of the fort, accompanied by the usual couched threat of massacre by the Indians in case of refusal. The demands was met by a defiant refusal. This was immediately followed by a cannonade from the gun-boats and howitzers which the British had landed. All night long the great guns played upon the fort without serious effect, and answered occasionally by the solitary 6-pound cannon possessed by the garrison, which was shifted from one block-house to another to give the impression that the works were armed with several great guns.

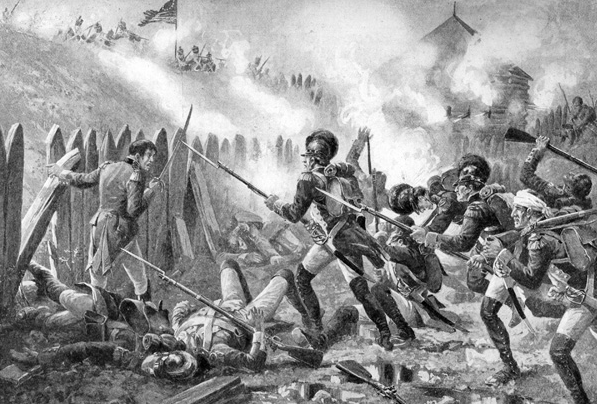

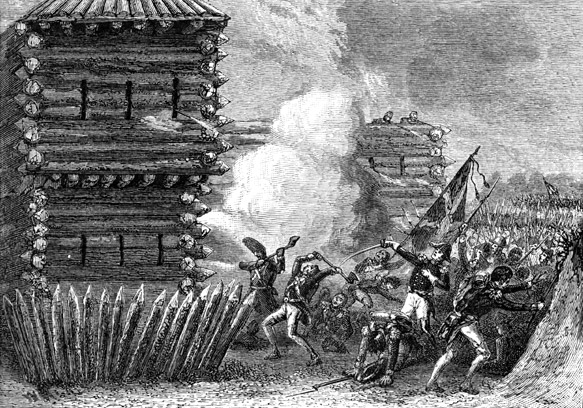

During the night the British dragged three 6-pound cannon to a point higher than the fort, and early in the morning these opened fire on the works. This continued many hours with very little effect, the garrison remaining silent. Proctor became impatient and his savage allies were becoming uneasy, for there were rumors of reinforcements on their way for the men in the fort; so he resolved to storm the work. At five o’clock in the afternoon of that hot August day, while the bellowing of distant thunder was heard from an angry tempest-cloud in the western sky, the British marched in two columns to assail the fort. At the same time some British grenadiers made a wide circuit through the woods to make a feigned attack at another point. As the two columns advanced, the artillery played incessantly upon the fort, and under cover of the smoke they had reached a position with fifteen or twenty paces of the strong pickets, before they were discovered. The garrison consisted of Kentucky “sharp-shooters,” whose rifles now opened a deadly fire upon the foe. The British columns wavered, but soon rallied; and the first, pushing over the glacis, leaped into the ditch to assail the palisades. “Cut away the pickets, my brave boys, and show the damned Yankees no quarter!” shouted Lieutenant-Colonel Short, their leader.

His voice was soon silenced. In a block-house that commanded the ditch in a raking position, the only cannon of the fort was masked. When that ditch was crowded with men, the port flew open and a terrible storm of slugs and grape-shot swept along the living wall with awful effect. The second column, led by Lieutenant Gordon, leaped into the ditch, and met a similar reception, to which was added a volley of rifle-balls. Short and Gordon, and many of their followers, were slain in the ditch. A precipitate and confused retreat followed, the British having lost, in killed and wounded, one hundred and twenty men, while only one man of the garrison was killed and several were wounded. The cowardly Indians, always afraid of cannon, had not joined in the fight, but were swift in the flight.

This gallant defence of Fort Stephenson commanded the greatest admiration, and Major Croghan received many honors. Congratulatory letters were sent to him. The ladies of Chillocothe, Ohio, bought and presented to him an elegant sword, and Congress voted him the thanks of the nation. Twenty-two years afterward, that body awarded him a gold medal for his bravery and skill on that occasion. This defence, so unexpected and successful, had a powerful effect upon the Indians. Tecumtha no longer believed in British invincibility, of which Proctor had boasted, and the British abandoned all hope of capturing these western American posts until they should become masters of Lake Erie.