Editor’s note: The following account of the Third Anglo-Ashanti War is extracted from Our Soldiers: Gallant Deeds of the British Army During the Reign of Queen Victoria, by W.H.G. Kingston (published 1899). All spelling in the original.

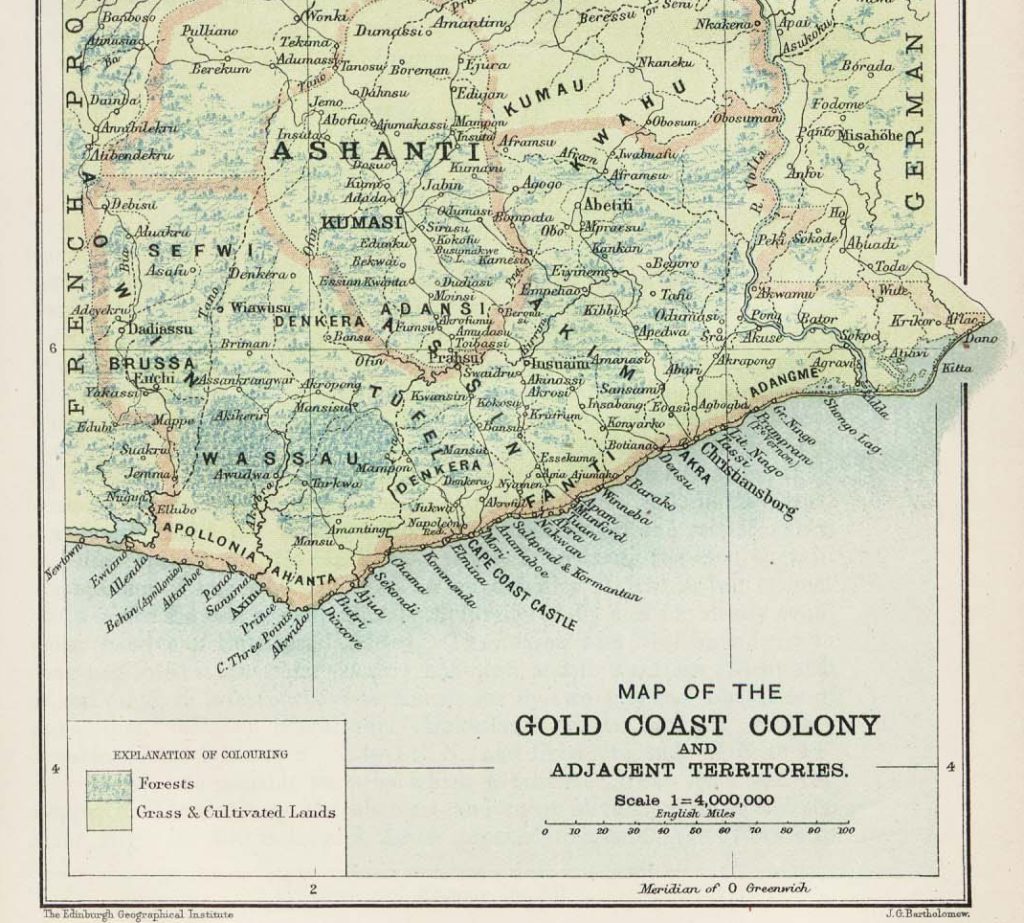

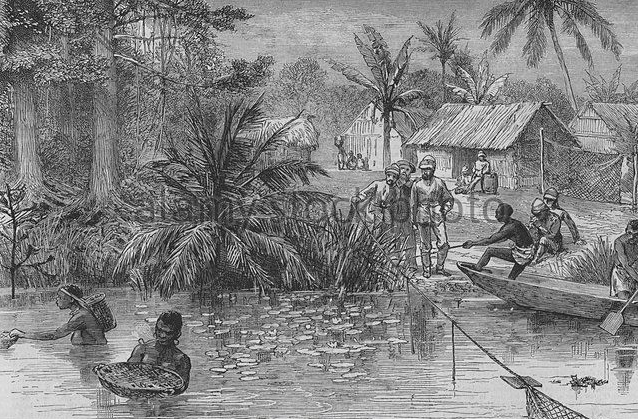

On that part of the West coast of Africa which runs east and west, extending from the Bight of Benin to Cape Palmas, a portion being known as the Gold Coast, are situated a number of forts, some of which belonged to the Dutch and Danes, who lately ceded them to the British Government.

The principal fort is Cape Coast Castle, and to the west of it is the late Dutch fort of Elmina.

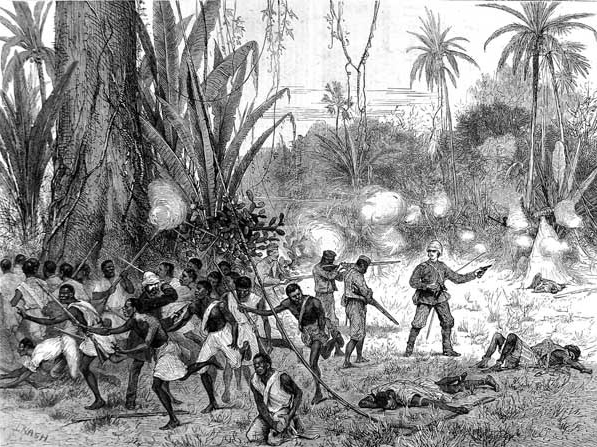

The largest river in this part of Africa is the Prah, which, running for some distance from the north-east to the south-west, takes an almost due southerly course, and falls into the sea about 20 miles west of Cape Coast Castle. The whole region is almost entirely covered by dense scrub or lofty trees, with a thick undergrowth of shrubs and creepers, through which it is impossible to pass, unless where native paths exist or a way has been cut by the axe of the pioneer; while in all directions marshes exist, emitting exhalations destructive to the health and lives of Europeans exposed to their noxious influences.

The Ashantees, a large and warlike tribe who had fought their way from the interior, established themselves early in the last century to the north and west of the Prah, and founded Coomassie as their capital, about 140 miles to the north of Cape Coast Castle. Having devastated the country by fire and sword, they soon after annexed the greater part of Denkera to their kingdom, driving the surviving inhabitants to the south-east, where they are at present settled near the Swat River, which falls into the sea between Cape Coast Castle and Elmina.

The country between Cape Coast Castle and the Prah is inhabited by the Fantis, a tribe which, although at one time warlike, have greatly degenerated. Neither the Dutch nor the English have attempted to subdue any of the neighbouring tribes; and though the people residing in the immediate vicinity of the forts have been friendly, the Europeans have throughout their occupancy been subject to serious attacks from the savages in the neighbourhood.

The most formidable of these foes have been the Ashantees, who have on several occasions threatened Cape Coast Castle, and numbers of the garrison marching out to drive them back have been cut off.

The Fantis have been, since the commencement of this century, constantly attacked by the Ashantees, and in 1820 they placed themselves under the protection of England. A fatal expedition for their defence was undertaken in 1824 by Sir Charles Macarthy, who, crossing the Prah with a small force without waiting for the main body of his troops, being deserted by the Fantis and surrounded by the Ashantees, was with all his forces cut to pieces, three white men only escaping.

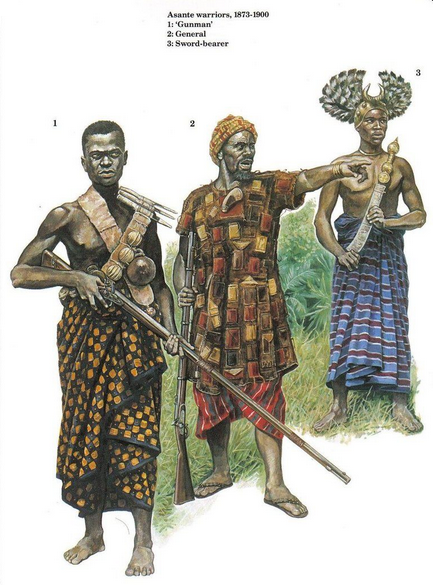

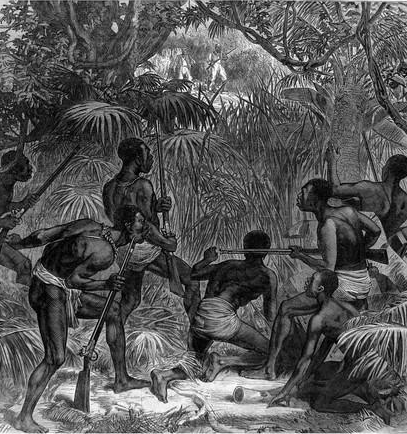

This and other successes over our native allies induced the reigning king of Ashantee, Coffee Calcalli, to hold the British power in contempt. The barbarous customs of the Ashantees almost surpass conception. Their religion is the grossest fetishism. Human life is utterly disregarded; and thousands of slaves are yearly slaughtered as sacrifices by the king, their bodies being thrown into a vast pit in the neighbourhood of his palace. In 1873, this black potentate having made alliances with the chiefs of other tribes, sent a large Ashantee force across the Prah, with the avowed intention of capturing Elmina, which he asserted the Dutch had no right to dispose of to the English. Destroying the Fanti villages in their course, they advanced to within a few days’ march of Cape Coast Castle. Every effort was made by Colonel Harley, who was then in command there, to induce the Fantis to withstand the enemy, while he collected such forces as were available for their support. One of the bravest and most disciplined races in that part of Africa are the Houssas, a body of whom were at once obtained from Lagos, and who, with some companies of the 2nd West India Regiment and a body of Fanti police, were marched to the front, under the command of Lieutenant Hopkins.

The Fantis, however, though far more numerous than their invaders, took to flight, and the force which had been sent to their assistance had to return.

The Ashantees now took possession of Dunquah, from whence they moved to the east towards Denkera. As serious apprehensions were entertained that both Elmina and Cape Coast Castle would be attacked, the English Government sent out H.M.S. Barracouta, Captain Fremantle, with a detachment of marines, under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Festing, of the Royal Marine Artillery.

They landed at Cape Coast Castle on the 9th of June, when Colonel Festing assumed command of the troops on the coast, and Captain Fremantle became senior naval officer on the station. Martial law was proclaimed; and as the inhabitants of the native town of Elmina showed a disposition to revolt, on the refusal of the chiefs to give up their arms the place was bombarded and set on fire, the rebels making their escape. A large body of Ashantees, two or three thousand strong, now approached Elmina, when they were gallantly attacked by Colonel Festing with the marines, and a party of bluejackets under Captain Fremantle, some men of the 2nd West India Regiment, and a body of Houssas.

The enemy advanced boldly along the plain, and were about to outflank the British force on the right, when Lieutenant Wells, R.N., of the Barracouta, attacked them with a heavy fire of Sniders, and drove them back, on which Colonel Festing, ordering the advance of the whole line, repulsed the enemy, who left 200 men dead on the field.

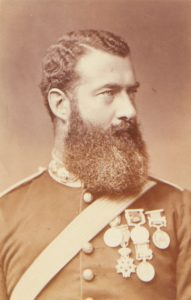

This was the first of several actions which ensued; but it was very evident that no adequate punishment could be inflicted on King Coffee and his subjects unless by a strong body of disciplined troops. This was the opinion of all the principal officers acquainted with the country. The British Government, however, not being at first thoroughly satisfied of the necessity of sending out troops from England, appointed Sir Garnet Wolseley, who had displayed his abilities as a general in the Red River Expedition, to proceed to Cape Coast Castle, with a well-selected staff of officers, and to make his report.

One of the most active officers at this time was Lieutenant Gordon, who had raised and drilled a body of Houssas, with whom he rendered good service during the war. He now formed a redoubt at the village of Napoleon, about five miles from Cape Coast, and several others being thrown up, the intermediate country to the south was well protected. A further body of marines arrived by the Simoom.

In the meantime Commodore Commerell, who had arrived in the Rattlesnake from the Cape of Good Hope, made an excursion with several other officers up the Prah, to communicate with the chiefs residing on its banks.

Having had an interview with the chiefs he found near the mouth of the river, he led his fleet of boats about a mile and a half up, when, without any warning, an enemy concealed in the bush opened a heavy fire on them. The commodore was badly wounded, and Captains Luxmoore and Helden were also severely hurt, as were several of the men. On this the commodore ordered the return of the boats to the Rattlesnake, when the town of Chamah was at once bombarded, and quickly destroyed.

In this unfortunate affair four men were killed and sixteen wounded, while so severe was Commodore Commerell’s wound, that he was ordered immediately to return to the Cape.

Space will not allow a description of the numerous engagements with the enemy, in which all the officers employed exhibited the greatest courage and endurance, although none surpassed Lieutenant Gordon and his Houssas in the services they rendered.

On the 2nd October, Sir Garnet Wolseley arrived at Cape Coast Castle in the Ambris, having previously touched at Sierra Leone, and made arrangements with the governor for raising men from the various tribes along the coast; steps were also immediately taken to form an army of Fantis. The major-general, however, was soon convinced that the attempt was hopeless; and, after a month’s experience of the native forces he was able to collect, supported as they were by marines, bluejackets, and West India regiments, he wrote home requesting that the regiments which had been selected might be immediately sent out.

In the meantime, Captain Glover, formerly of the navy, who had served as administrator of the Government at Lagos, proposed a plan to raise a force of 10,000 natives, and to march from the east on Coomassie, the base of operations being on the river Volta, on which some steam-launches and canoes were to be placed. Captain Glover’s plan being sanctioned, he at once proceeded out with the officers he had selected to act under him.

He was now busily employed in raising the proposed troops, which, from a thorough knowledge of the people, he succeeded in doing in the most complete manner.

One of Sir Garnet Wolseley’s first exploits was a well-conducted attack on several of the villages in the neighbourhood of Elmina held by the Ashantees. Keeping his plan secret until the moment the march was commenced, he was able to surprise the enemy, who, however, stood their ground until put to flight by the rockets and the Snider rifle. Several officers and men were, however, wounded—Colonel McNeill badly in the wrist, as was also Captain Fremantle.

The seamen and marines had been up all night, and marched 21 miles under a burning sun, yet there were only two cases of sunstroke, and only four men were admitted to hospital the following day.

Captain Rait and Lieutenant Eardley Wilmot, of the Royal Artillery, had drilled a number of Houssas as gunners for Gatling guns and rockets, who afterwards rendered admirable service.

Besides Captain Rait’s artillery, two efficient regiments had been formed of between 400 and 500 men each, from the bravest tribes, the one under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Wood, the other under that of Major Russell. Both these corps were well drilled by experienced English officers, and on all occasions exhibited the greatest bravery.

So well-conducted were the attacks made on the Ashantee forces which had invaded the Fanti territory, that at length, towards the end of October, they broke up their camp and began to retreat over the Prah. They were closely pursued; but many of the native allies, as on other occasions, refusing to proceed, the difficulty of carrying on reconnaissances fell mostly on the English officers.

In this work Lord Gifford especially distinguished himself. Colonel Festing commanded the force employed in the pursuit. He had with him Lieutenant Eardley Wilmot, in charge of eight Houssas of Rait’s artillery. While pushing on gallantly in front, Lieutenant Wilmot was wounded in the arm, yet in spite of this he continued under fire, until an hour later he was shot through the heart; and Colonel Festing, when bringing in his body from where it was lying, was wounded by a slug in the hip.

Abrakrampa, one of the British advance posts, was garrisoned by the black regiment commanded by Major Russell, who had with him also a party of marines and bluejackets. He had received orders to send the latter back to Cape Coast, but just as they were about to march he received information that his camp would certainly be attacked. The report proved to be true. The enemy came on in great force; but each time that they attempted to break out of the bush, they were driven back by the hot fire kept up by the little garrison.

Major Russell immediately despatched a requisition for assistance, when a body of marines and bluejackets from the ships in the roads were landed and sent off. The Ashantees again and again renewed the attack, but were each time driven back.

The British force marching to the relief of the place suffered greatly from fatigue. They arrived, however, in time to assist in driving back the enemy, who now retreated towards the Prah at a more rapid rate than heretofore. While in pursuit of the enemy, large numbers of the native allies again took to flight, proving how utterly unreliable they were.

Sir Garnet Wolseley’s chief object now was, having driven the enemy before him, to construct a road in the direction of Coomassie, and prepare halting-places for the European troops which were soon expected out.

Sickness, however, rendered a considerable number of the English officers incapable of duty.

The pursuit of the enemy by the force under Colonel Wood was especially harassing work. He and many of his officers were suffering from fever. The Ashantees frequently halted and fired on their pursuers, though on each occasion driven back.

As many bluejackets as could be spared from the ships were now landed, and several officers arrived out from England. The major-general was able to report on the 15th December 1873—“That the first phase of this war had been brought to a satisfactory conclusion by a few companies of the 2nd West India Regiment, Rait’s artillery, Gordon’s Houssas, and Wood’s and Russell’s regiments, admirably conducted by the British officers belonging to them, without the assistance of any English troops except the marines and bluejackets, who were on the station on his arrival.” The Fanti country being cleared, a road towards the Prah was now energetically pushed forward. It was 12 feet wide, cleared of stumps or roots, swamps were either drained or avoided, or causeways made over them, and all the streams were bridged. This task was confided to Major Home, of the Royal Engineers.

The rough clearing of the first 25 miles had, however, already been performed by Lieutenant Gordon.

Stations were selected, and huts erected for the accommodation of the troops, and for stores and provisions. Means were taken to secure an ample supply of water, either by digging wells or from streams in the neighbourhood. At Prahsu the river Prah makes a sharp bend, within which a large camp was formed, with shelter for 2000 European troops, an hospital, and storehouses. Complete arrangements were made for the accommodation of the sick. The great difficulty was to obtain native carriers, who frequently deserted as soon as they were collected; and it was not until some time had passed that the transport service could be arranged in a satisfactory manner.

The plan which the major-general had arranged for the campaign was as follows:—The main body, consisting of three battalions of European troops, the Naval Brigade, Wood’s and Russell’s regiments and Rait’s artillery, was to advance from Prahsu by the Coomassie road. On the extreme right, a native force under Captain Glover was to cross the Prah near Assum, and, as a connecting link between him and the main body, a column composed of natives, under the command of Captain Butler, 69th Regiment, was to cross the same river lower down; while, on the extreme left, another column of natives, commanded by Captain Dalrymple of the 88th Regiment, was to advance by the Wassaw road on Coomassie.

On the 26th December, the major-general with his staff left Cape Coast Castle for Prahsu, which he reached on the 2nd January. Here the Naval Brigade arrived the following day.

The disembarkation of the regular troops commenced the 1st of January at 1:45, and by 6:35 that evening the whole of the troops had landed, and the brigade had reached Inquabun, six miles from Cape Coast Castle.

They consisted of the 42nd Highlanders, the Rifle Brigade, a detachment of the Royal Engineers, the 23rd Fusiliers, a detachment of the Royal Artillery, numbering in all 2504 men. As, however, there was great difficulty in obtaining transport, the Fusiliers and Royal Artillery were re-embarked, to remain on board the ships until required. Two hundred of the Fusiliers were afterwards re-landed, and marched to the front. Besides these, there were the 2nd West India Regiment, of 350 men, Rait’s artillery, 50 men, and Wood’s and Russell’s regiments, numbering together 800, afterwards increased by a detachment of the 1st West India Regiment, lately landed.

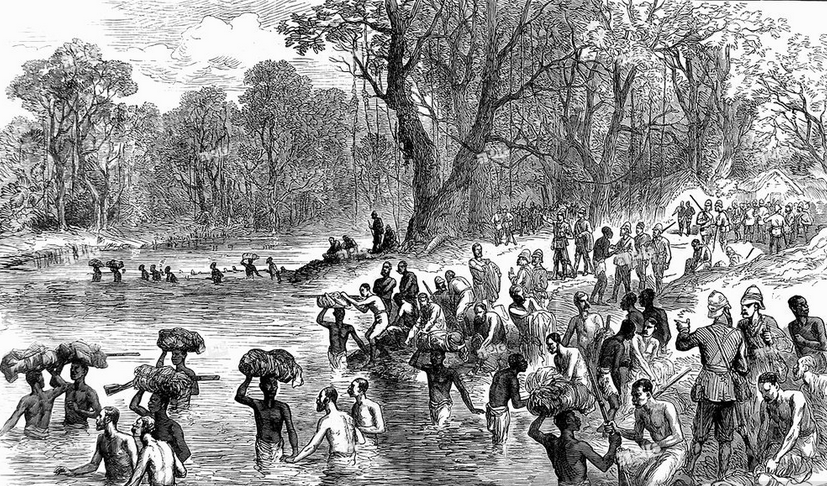

During the early part of January, the whole of the British troops reached Prahsu, and on the 20th, the bridge across the Prah being finished, the force intended for the attack on Coomassie marched out of the camp.

Lord Gifford, in command of a well-trained body of native scouts, had previously gone forward, followed by Russell’s and Wood’s regiments, which obtained possession of the crest of the Adansi Hills. Lord Gifford pushing ahead, the enemy’s scouts retreated before him, and the inhabitants deserted the villages. The king, it was evident, by this time was seriously alarmed, and, hoping for peace, released the European prisoners in his hands. He first sent in Mr Kuhne, a German missionary, who was followed by Mr Ramseyer, another missionary, and his wife and their two children, and Monsieur Bannat, a French merchant, from whom much important information was obtained. As the army advanced, the villages taken possession of were fortified and garrisoned, so that communication with the rear should be kept up and the sick carried back to hospital. Already a considerable number of officers and men were suffering from sickness. Captain Huyshe died the day before the major-general left Prahsu. Thus, out of the whole European force of 1800 men forming the main body, 215 men and 3 officers were unfitted for duty.

Fommanah, a large village 30 miles from Coomassie, having been deserted by the enemy, was entered on the 24th. The king sent letter after letter to Sir Garnet Wolseley petitioning for peace, but as he did not forward the hostages which were demanded, the army continued its advance, while the answer sent to him was “that the governor meant to go to Coomassie.”

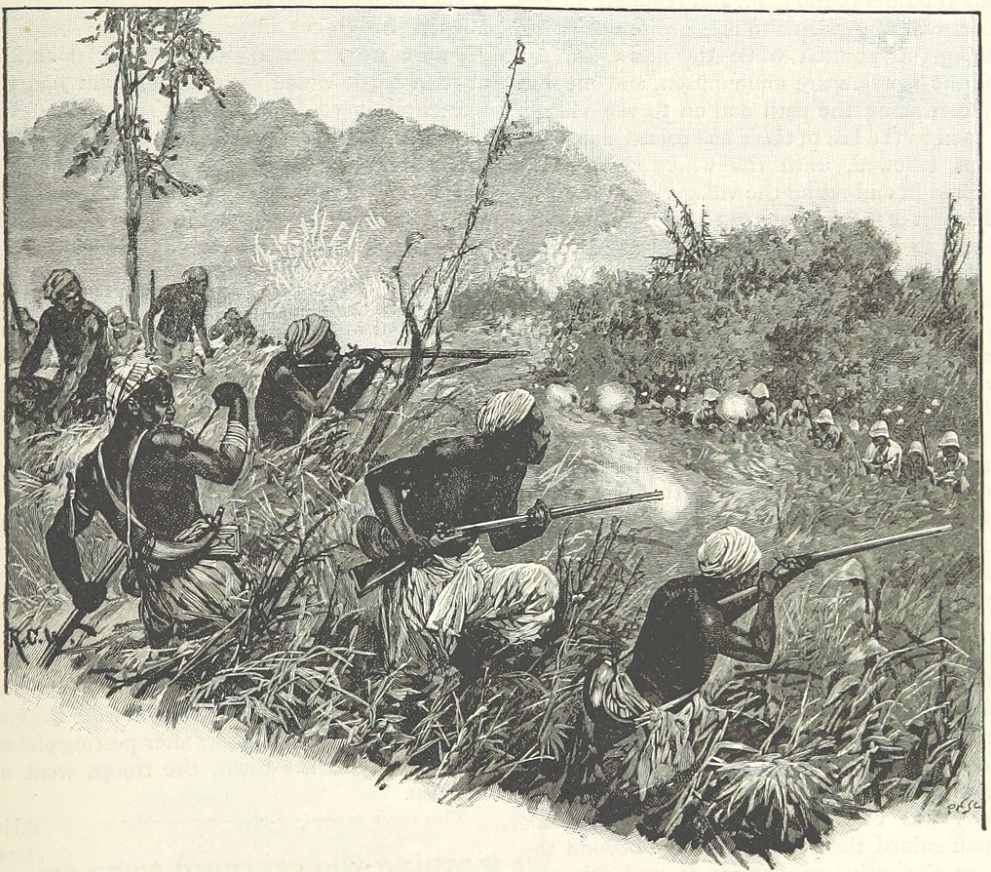

In an attack on the village of Borborassie, in which the Naval Brigade, a company of Fusiliers, and another of Russell’s regiment, with Rait’s artillery, were engaged, Captain Nicol, who led the advance, was unhappily shot dead, the first officer to fall north of the Prah. Information being received that the enemy was posted near the villages of Amoaful and Becquah, it was resolved immediately to attack them. The nature of the ground over which the operations were carried on must be described.

Excepting where the clearings for the villages existed, or native paths, the whole country was covered thickly with lofty trees, from which hung creepers innumerable, while below was thick brushwood, through which the pioneers had to cut a way before the troops could advance. Such a region afforded the enemy ample means of forming ambushes as well as for fighting under cover, of which they did not fail to take full advantage. The only other openings to be found were where swamps had prevented the growth of trees. Such was the difficult country in which Sir Garnet Wolseley had to manoeuvre his troops. The army advanced, with Lord Gifford’s scouts skirmishing in front, Rait’s guns and rockets leading, followed by the 42nd Highlanders, the 23rd Fusiliers, and the Rifle Brigade in succession, and on either flank the Naval Brigade and Russell’s and Wood’s regiments,—that on the right under command of Colonel Wood, and on the left of Colonel McLeod.

Lord Gifford, with 40 scouts, pushing ahead early in the morning, occupied the village of Egginassie by a rush. On the other side the enemy was found in considerable force. On this, Brigadier Sir Archibald Alison sent two companies of the 42nd Highlanders, forming the advance guard, up the main road to the front, and a section up a path which branched off to the left. Being soon hotly engaged, they were quickly supported by other companies under Major Macpherson, and the remainder of the regiment was immediately afterwards pushed forward. As company after company descended, their pipes playing, they were rapidly lost to sight in the thick smoke beneath, and their position could only be judged of by the sharp crack of their rifles, in contradistinction to the dull roar of the Ashantee musketry.

It was with the greatest difficulty, when fresh companies were sent to the support of those in action, that the latter could find their friends in the midst of the enemy’s fire. The engineer labourers under Captain Buckle were cutting paths in the required directions, but so heavy a fire was brought to bear by the enemy, that their progress was much delayed. While at this time engaged in urging on his men, Captain Buckle fell mortally wounded. By one of the paths thus formed, Lieutenant Palmer brought his rockets into action, and, covered by their fire, two of the companies of Russell’s regiment, led by Captain Gordon, made a splendid dash at the enemy. The Naval Brigade, under Captain Luxmoore, were engaged at the same period in exchanging a heavy fire with the Ashantees, who were making desperate attempts to retake the village. Before long, Major Macpherson and several other officers were wounded. Captain Rait’s guns were now sent across the swamp, to attack a spot on which a dense mass of the enemy were collected together. After 14 or 15 rounds, which caused tremendous slaughter, they showed signs of giving way, and a rush being made, their position was carried. On the summit was found a large camp, in which their main body had been posted. This being quickly traversed by the British troops, the Ashantees again made a bold stand from a ridge behind it.

Once more Rait’s guns were brought into action, followed by a heavy rifle fire, when, another charge being made, the fresh position taken up by the enemy was also carried. In the meantime, the right column, under Colonel Wood, which had been supported by the Fusiliers, was hotly engaged, and a considerable number of men were wounded, Colonel Wood and his aide-de-camp among them. So fierce was the opposition, that a second support of two companies of the Rifle Brigade was next ordered up. Pushing forward, they gallantly drove the enemy from their cover, and about half-past twelve the Ashantees took to flight.

As the cheers in front announced that the battle was gained, a rapid fire was heard in the direction of Quarman, showing that the Ashantees were attempting to cut off the communication with the rear. Four companies of the Rifle Brigade were accordingly ordered back, and so actively did they ply their rifles, that in less than an hour the Ashantees were put to flight. Another attack was, however, made on the right and rear of Quarman, by one of the principal Ashantee generals, but the enemy was gallantly held in check by its small garrison until the arrival of a company of the Rifle Brigade.

In the meantime Amoaful had been taken by a gallant rush of the 42nd Highlanders, led by Major Cluny Macpherson, and here the major-general established his headquarters.

The action altogether had lasted twelve hours, extending along two and a half miles of road. During the greater part of the time the firing was incessant,—the loss suffered by the 42nd being proof of its severity, nearly every fourth man having been hit. The enemy must have lost upwards of 2000 men in killed and wounded.

In the action, besides Captain Buckle, there were two privates of the 42nd and one of Wood’s regiment killed. Of wounded, there were 15 military officers, and 147 men; 6 officers of the Naval Brigade, and 26 men. As short a time as possible was spent at Amoaful, when the force again advanced on the 2nd of February.

The advance guard was under Colonel McLeod, the main body under Brigadier-General Sir Archibald Alison. The troops carried two days’ rations in their haversacks, a similar quantity being conveyed by the spare hammock bearers. A fifth day’s rations were to be brought forward to them.

Colonel McLeod, pushing on, found but little opposition. The force was now concentrated at a place called Aggemmamu, within fifteen miles of Coomassie.

Sir Garnet now announced his intention of making a dash on Coomassie. The soldiers were asked whether they would undertake to make their rations for four days last if necessary for six. The answer was, as may be supposed, “Most willingly.” Leaving their baggage under the care of such men as were too weakly to march, the army advanced on the morning of the 3rd.

As usual, Lord Gifford with his scouts went ahead, followed by Russell’s regiment under Colonel McLeod. In a short time the enemy was encountered. After a sharp and short action, however, he was driven back, but with some loss on the side of the British. The advance guard pushed on until within a short distance of Coomassie, when messengers arrived from the king again entreating for peace, at the same time stating that there were 10,000 men on the other side of the river, who would fight if the British advanced. Sir Garnet Wolseley returned word, “that unless the queen and prince royal should be put into his hands, the march would be continued.”

The advance guard reached the river Ordah at 2:10 p.m. It was found to be fifty feet wide and waist deep. Russell’s regiment at once passed over, forming a covering party to the Engineers, who immediately set to work to throw a bridge across for the passage of the European troops, while clearings were made on the south bank, and rush huts thrown up in which the British soldiers bivouacked. At first some apprehensions were entertained that a night-attack would be made, but a heavy thunderstorm coming on, during which the flintlocks of the enemy would have been useless, rendered that improbable.

By daybreak on the 4th, the bridge over the Ordah was completed, Major Home, of the Engineers, having worked at it all night throughout the whole of the tornado and drenching rain.

As no hostages had arrived, it was expected that another battle would have to be fought.

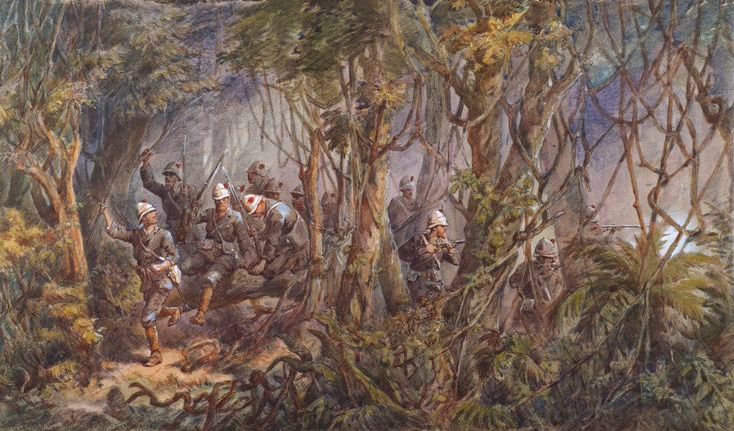

At an early hour the advance guard pushed on, the Naval Brigade being left at the bridge to guard the passage until the baggage had crossed. Directly the troops advanced, the enemy opened fire. The native troops on this occasion firing wildly, Colonel McLeod ordered a company of the Rifle Brigade and the 7-pounder gun under Lieutenant Saunders to the front.

The enemy pressing the advance, a vigorous flank fire being also opened on the troops under Sir Archibald Alison, reinforcements were ordered up. Colonel McLeod continued steadily to advance, Lieutenant Saunders’ gun clearing the road, when the Rifles again pushed forward, until the village of Ordahsu was carried and a lodgment effected there.

In this skirmish Lieutenant Eyre was mortally wounded, and several of the men were severely hurt, although the enemy did not fight with the same obstinacy as at Amoaful. As the village was approached, a tremendously heavy fire was opened on both flanks of the British force. The Rifle Brigade and the Fusiliers, with two of Rait’s guns, having now got up to the village, under Sir Archibald Alison’s command, the force was ordered to move on.

At that moment the enemy commenced a vigorous attack on the village, so that the Rifle Brigade and Fusiliers had to be thrown into the bush to check them. According to the brigadier’s request, the 42nd were pushed forward, the object being to break through the enemy who appeared in force in front. The Highlanders were quickly sent on, and the major-general with the headquarters entered the village immediately after them. A short halt, however, was required, to allow the baggage to arrive.

During this time the enemy pressed boldly up to the village, firing volleys of slugs, one of which struck the major-general on the helmet, fortunately at a part where the leather band prevented it entering.

About noon, the 42nd, with Rait’s artillery, led the attack on the enemy’s front, for the purpose of breaking through and pushing on direct for Coomassie, followed by the Rifle Brigade. They had not got far before a tremendous fire was opened on the head of the column from a strong ambuscade behind a fallen tree, and several men were knocked over, but the flank companies working steadily through the bush, the leading company sprang forward with a cheer. The pipes struck up, and the ambuscade was carried. Then, without stop or stay, the 42nd rushing on cheering, their pipes playing, officers to the front, ambuscade after ambuscade was successfully carried, and village after village won in succession, until the whole of the Ashantee army broke and fled in the wildest disorder down the pathway towards Coomassie. The ground was covered with traces of their flight. Umbrellas, war chairs of their chiefs, drums, muskets, killed and wounded, strewed the way. No pause took place until a village about four miles from Coomassie was reached, when the absolute exhaustion of the men rendered a short halt necessary.

Meanwhile the attack on the village continued, and the enemy were allowed to close around the rear, Ordahsu, however, being strongly guarded.

On the arrival of the major-general, he ordered an advance of the whole force on Coomassie. It was nearly five o’clock before the troops again moved forward. The village of Karsi, the nearest to Coomassie, was passed without opposition. When close upon the city, a flag of truce was received by the brigadier, who forwarded it with a letter to Sir Garnet Wolseley, whose only reply was, “Push on.” On this the brigadier immediately advanced, and, passing the Soubang swamp which surrounds the city, entered the great market-place of Coomassie, without opposition, about 5:30. The major-general himself arrived at 6:15, when the troops formed on parade, and, at his command, gave three cheers for Her Majesty the Queen.

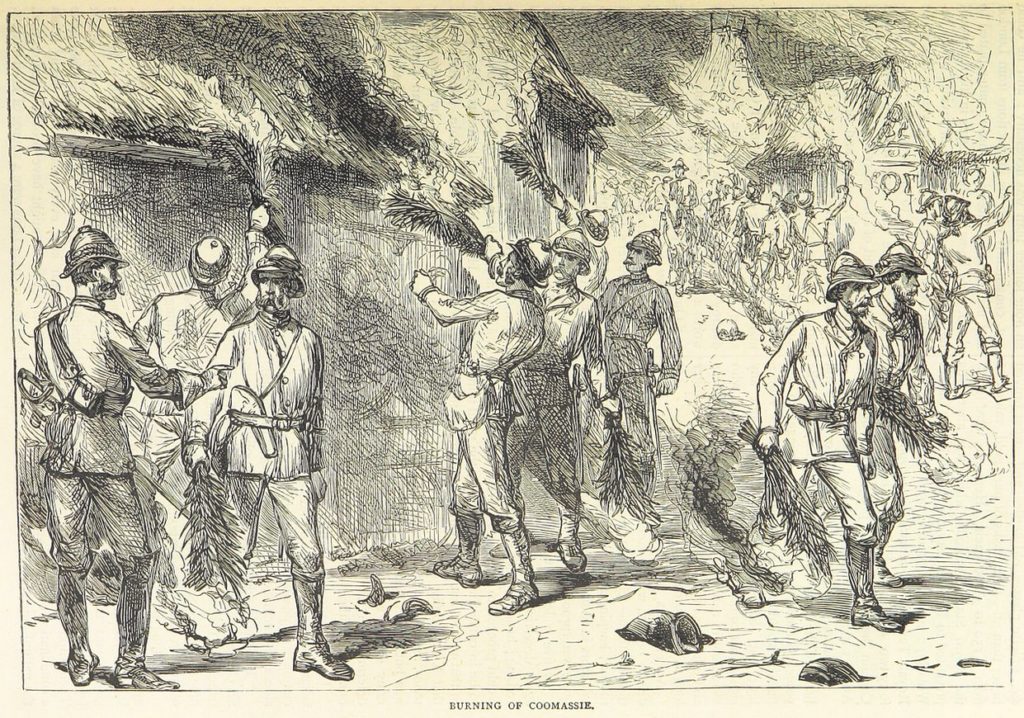

The town was full of armed men, but not a shot was fired. The brigadier had so placed the artillery that it could sweep the streets leading to the market-place, and had thrown out the necessary pickets. A party was sent down to the palace, under the guidance of an Englishman who had long been a resident at Coomassie; but the king, queen-mother, and prince, with all other persons of distinction, had fled. Due arrangements were made to preserve order. The major-general issued a proclamation, threatening with the punishment of death any person caught plundering. The troops were exposed to much danger, flames bursting out in several directions, the work of the Fanti prisoners who had been released. The great palace of the king was entered,—a building far superior to the ordinary habitations of the natives,—and was found to contain treasures of all sorts, and evidence also of the fearful atrocities committed within it; while close to it was seen the dreadful pit into which the bodies of those slaughtered almost daily by the king’s command were thrown.

In vain Sir Garnet Wolseley waited for the king to fulfil his promise; neither any part of the sum demanded, nor the hostages, had been delivered. To remain longer at Coomassie was hazardous in the extreme. The rains had already commenced, and the rivers, which had been crossed with ease, were now much swollen.

For the sake of the health of the troops, the major-general resolved, therefore, having destroyed the town and palace, to retreat. That the enemy might not be aware of his intentions, a report was circulated that the army would advance in pursuit of the king, and that any Ashantee found in the town after six o’clock would be shot. This effectually cleared out the natives.

Prize agents were appointed to take charge of the riches in the palace. Arrangements were made for destroying it on the following morning, and setting the whole town on fire.

Early the next morning the return march began. The rear company of the 42nd Highlanders remained at the south end of the market-place while the guard was removed from the palace. The city was then set on fire, and the mines for the destruction of the palace exploded,—the dense columns of smoke which curled up in the sky showing the King of Ashantee and all his subjects that the white man had not failed to keep his word. Gallant Colonel McLeod remained until the last of the engineers and sappers had passed to the front; he then waved his hand as a signal for the rear company to march, and Coomassie was abandoned to the flames.

The troops on their return march, although they encountered some difficulties, were not molested, so thoroughly and completely had the Ashantees been defeated. As a further proof of this, ambassadors from the king overtook the army on the 12th, bringing upwards of 1000 ounces of gold, as part of the indemnity of the 50,000 ounces demanded, and returned with a treaty of peace for the black monarch to sign. The forts which had been constructed were destroyed, the sick and wounded, with the stores, sent on, and the major-general and his staff reached Cape Coast Castle on the 19th of February.

The Naval Brigade, consisting of 265 men and 17 officers, rendered valuable service throughout the campaign, and fought on all occasions with most dashing courage. Though only one was killed, 63 were wounded in action, while several others were killed and wounded during the operations which took place along the coast, to punish several of the petty chiefs who had sided with the Ashantees.

One of the most gallant performances of the campaign was the ride across the country, from the eastward, by Captain Sartorious, who with 20 followers passed through Coomassie five days after the army had quitted it, and, though fired on twice by the enemy, safely arrived at Prahsu. The following day, Captain Glover, R.N., having marched from the Volta, entered the city at the head of 4600 native allies. Here King Coffee sent him a token of submission by the hands of an ambassador, in the shape of a plateful of gold, which he returned, and then proceeded southward with his forces into friendly territory, having performed an exploit which, for daring, intrepidity, judgment, and the perseverance with which it was carried out, stands almost unrivalled.

Most of the officers engaged in the expedition were promoted, but on two only—Lord Gifford and Sergeant McGaw of the 42nd—was the Victoria Cross bestowed,—an honour which, by the unanimous voice of all who witnessed their behaviour, they richly deserved.

The Commander-in-Chief also recommended Captain A.F. Kidston of the 42nd, Private George Cameron, and Private George Ritchie, for the same honour.

The officers killed in action were Lieutenant E. Wilmot, R.A., Lieutenant Eyre, 90th Regiment, Captain Nicol, Hants Militia, Captain Buckle, RE; while three died from the effects of the climate,—Lieutenant the Honourable A. Charteris, A.D.C., Captain Huyshe, D.A.Q.M.G., Lieutenant E. Townshend, 16th Regiment; while seven others were wounded.

Great read, saved. Who supplied the Ashanti with muskets?

My guess is they obtained them from unscrupulous European traders, who regarded firearms as just another commodity to sell. This was common practice in the Far East, and presumably Africa too.