Editor’s note: The following is extracted from A History of Sea Power, by William Oliver Stevens and Allan Westcott (published 1920). All spelling in the original.

In the Dutch Wars of the 17th century the British navy may be said to have caught its stride in the march that made Britannia the unrivaled mistress of the seas. The defeat of the Armada was caused by other things besides the skill of the English, and the steady decline of Spain from that point was not due to that battle or to any energetic naval campaign undertaken by the English thereafter. In fact, save for the Cadiz expedition of 1596, in which the Dutch coöperated, England had a rather barren record after the Armada campaign down to the middle of the 17th century. During that period the Dutch seized the control of the seas for trade and war. They appropriated what was left of the Levantine trade in the Mediterranean, and contested the Portuguese monopoly in the East Indies and the Spanish in the West. Indeed the Dutch were at this time freely acknowledged to be the greatest sea-faring people of Europe.

When the Commonwealth came into power in England the new government turned its attention to the navy, which had languished under the Stuarts. A great reform was accomplished in the bettering of the living conditions for the seamen. Their pay was increased, their share of prize money enlarged, and their food improved. At the same time, during the years 1648-51, the number of ships of the fleet was practically doubled, and the new vessels were the product of the highest skill in design and honest work in construction. The turmoil between Roundhead and Royalist had naturally disorganized the officer personnel of the fleet. Prince Rupert, nephew of Charles I, had taken a squadron of seven Royalist ships to sea, hoping to organize, at the Scilly Islands or at Kinsdale in Ireland, bases for piratical raids on the commerce of England, and it was necessary to bring him up short. Moreover, Ireland was still rebellious, Barbados, the only British possession in the West Indies, was held for the King, and Virginia also was Royalist. To establish the rule of the Commonwealth Cromwell needed an efficient fleet and an energetic admiral.

For the latter he turned to a man who had won a military reputation in the Civil War second only to that of the great Oliver himself, Robert Blake, colonel of militia. Blake was chosen as one of three “generals at sea” in 1649. As far as is known he had never before set foot on a man of war; he was a scholarly man, who had spent ten years at Oxford, where he had cherished the ambition of becoming a professor of Greek. At the time of his appointment he was fifty years old, and his entire naval career was comprised in the seven or eight remaining years of his life, and yet he so bore himself in those years as to win a reputation that stands second only to that of Nelson among the sea-fighters of the English race.

Blake made short work of Rupert’s cruising and destroyed the Royalist pretensions to Jersey and the Scillies. One of his rewards for the excellent service rendered was a position in the Council of State, in which capacity he did much toward the bettering of the condition of the sailors, which was one of the striking reforms of the Commonwealth. His test, however, came in the first Dutch War, in which he was pitted against Martin Tromp, then the leading naval figure of Europe.

In the wars with Spain, English and Dutch had been allies, but the shift of circumstances brought the two Protestant nations into a series of fierce conflicts lasting throughout the latter half of the 17th century. The outcome of these was that England won the scepter of the sea which she has ever since held. The main cause of the war was the rivalry of the two Page 170 nations on the sea. There were various other specific reasons for bad feeling on both sides, as for instance a massacre by the Dutch of English traders at Amboyna in the East Indies, during the reign of James I, which still rankled because it had never been avenged. The English on their side insisted on a salute to their men of war from every ship that passed through the Channel, and claimed the rights to a tribute, of all herrings taken within 30 miles off the English coast.

Cromwell formulated the English demands in the Navigation Act of 1651. The chief of these required that none but English ships should bring cargoes to England, save vessels of the country whence the cargoes came. This was frankly a direct blow at the Dutch carrying trade, one to which the Dutch could not yield without a struggle.

For this struggle the Netherlanders were ill prepared. The Dutch Republic was a federation of seven sovereign states, lacking a strong executive and torn by rival factions. Moreover, her geographical position was most vulnerable. Pressed by enemies on her land frontiers, she was compelled to maintain an army of 57,000 men in addition to her navy. As the resources of the country were wholly inadequate to support the population, her very life depended on the sea. For the Holland of the 17th century, as for the England of the 20th, the fleets of merchantmen were the life blood of the nation. Unfortunately for the Dutch, this life blood had to course either through the Channel or else round the north of Scotland. Either way was open to attacks by the British, who held the interior position. Further, the shallows of the coasts and bays made necessary a flat bottomed ship of war, lighter built than the English and less weatherly in deep water.

In contrast the British had a unity of government under the iron hand of Cromwell, they had the enormous advantage of position, they were self-sustaining, and their ships were larger, stouter and better in every respect than those of their enemies. Hence, although the Dutch entered the conflict with the naval prestige on their side, it is clear that the odds were decidedly against them.

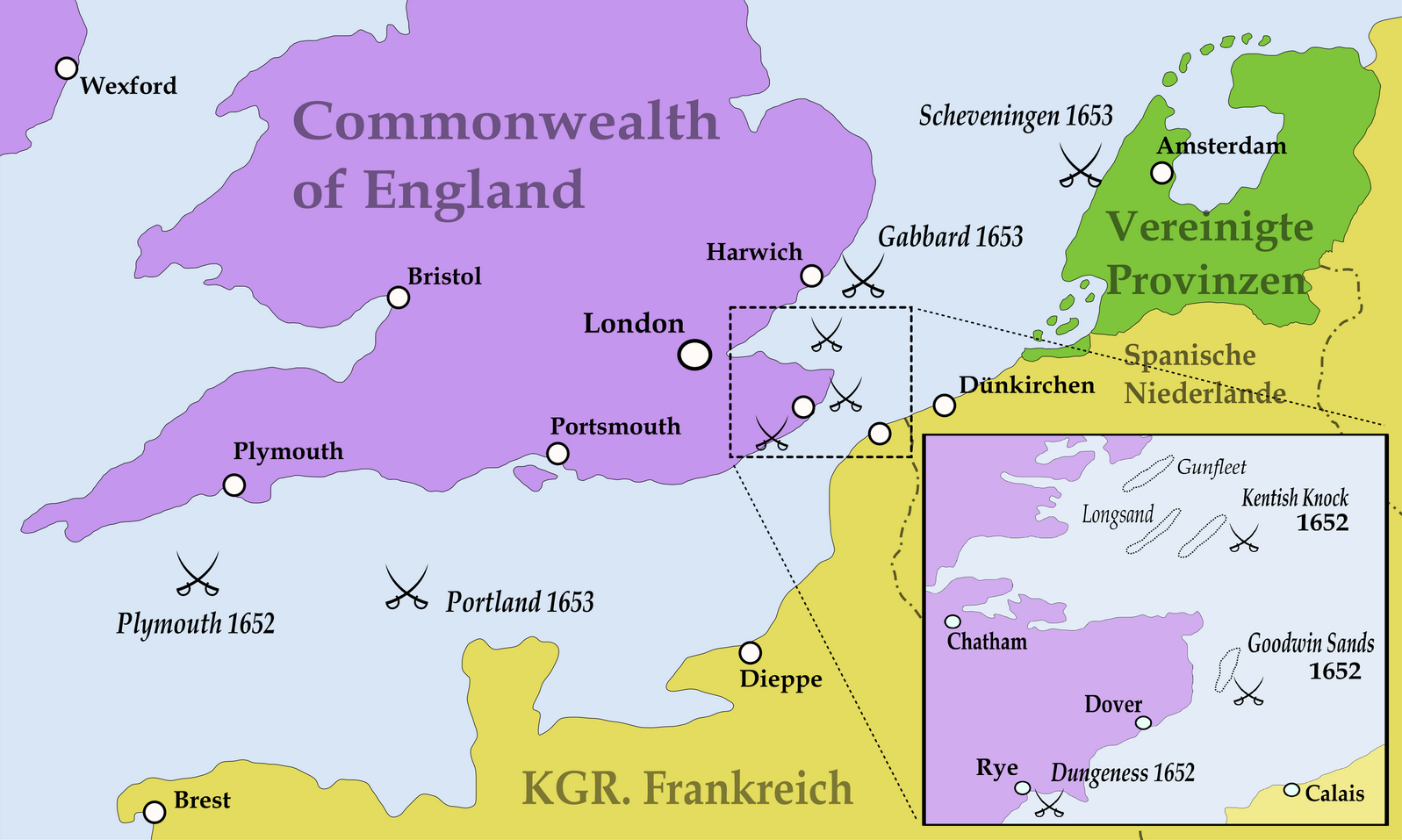

The First Dutch War

The fighting did not wait for a declaration of war. Blake met Tromp, who was convoying a fleet of merchantmen, off Dover on May 19, 1652. On coming up with him Blake fired guns demanding the required salute. Tromp replied with a broadside. Blake attacked with his flagship, well ahead of his own line, and fought for five hours with Tromp’s flagship and several others. The English were outnumbered about three to one, and Blake might have been annihilated had not the English admiral, Bourne, brought his squadron out from Dover at the sound of the firing and fallen upon Tromp’s flank. As the Dutch Admiral’s main business was to get his convoy home, he fell back slowly toward the coast of France, both sides maintaining a cannonade until they lost each other in the darkness. Apparently there was little attempt at formation after the first onset; it was close quarters fighting, and only the wild gunnery of the day saved both fleets from enormous losses. As it was, Blake’s flagship was very severely hammered.

Following this action, Tromp reappeared with 100 ships, but failed to keep Blake from attacking and ruining the Dutch herring fisheries for that year. This mistake temporarily cost Tromp his command. He was superseded by DeWith, an able man and brave, but no match for Blake. On September 28, 1652, Blake met him off the “Kentish Knock” shoal at the mouth of the Thames. In order to keep the weather gage, which would enable him to attack at close quarters, Blake took the risk of grounding on the shoal. His own ship and a few others did ground for a time, but they served as a guide to the rest. In the ensuing action Blake succeeded in putting the Dutch between two fires and inflicting a severe defeat. Only darkness saved the Dutch from utter destruction.

The effect of this victory was to give the English Council of State a false impression of security. In vain Blake urged the upkeep of the fleet. Two months later, November 30, 1652, Tromp, now restored to command, suddenly appeared in the Channel with 80 ships and a convoy behind him. Blake had only 45 and these only partly manned, but he was no man to refuse a challenge and boldly sailed out to meet him. It is said that during the desperate struggle—the “battle of Dungeness”—Blake’s flagship, supported by two others, fought for some time with twenty of the Dutch. As Blake had the weather gage and retained it, he was able to draw off finally and save his fleet from destruction. All the ships were badly knocked about and two fell into the hands of the enemy. Blake came back so depressed by his defeat that he offered to resign his command, but the Council of State would not hear of such a thing, handsomely admitted their responsibility for the weakness of the fleet, and set at work to refit. Meanwhile for the next three months the Channel was in Tromp’s hands. This is the period when the legend describes him as hoisting a broom to his masthead.

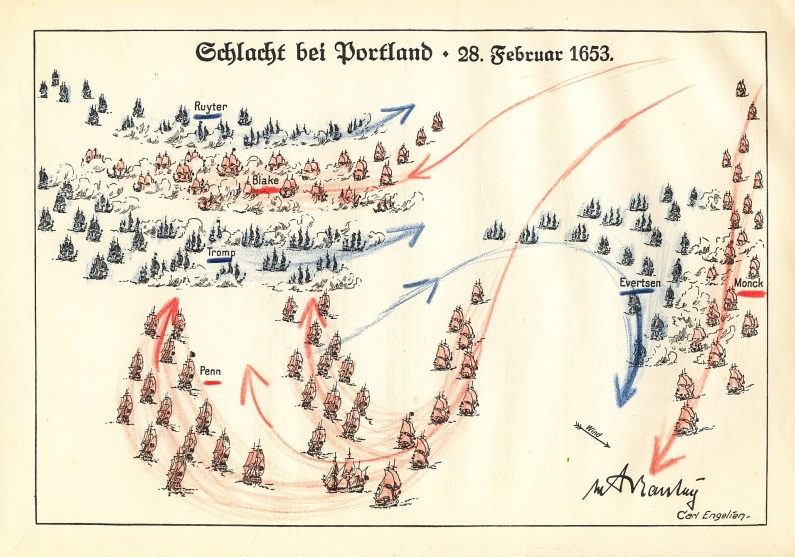

By the middle of February the English had reorganized their fleet and Blake took the sea with another famous Roundhead soldier, Monk, as one of his divisional commanders. At this time Tromp lay off Land’s End waiting for the Dutch merchant fleet which he expected to convoy to Holland. On the 18th the two forces sighted each other about 15 miles off Portland. Then followed the “Three Days’ Battle,” or the battle of Portland, one of the most stubbornly contested fights in the war and its turning point.

In order to be sure to catch Tromp, Blake had extended his force of 70 or 80 ships in a cross Channel position. Under cover of a fog Tromp suddenly appeared and caught the English fleet divided. Less than half were collected under the immediate command of Blake, only about ten were in the actual vicinity of his flagship, and the rest were to eastward, especially Monk’s division which he had carelessly permitted to drift to leeward four or five miles. As the wind was from the west and very light, Monk’s position made it impossible for him to support his chief for some time. Tromp saw his opportunity to concentrate on the part of the English fleet nearest him, the handful of ships with Blake. The latter had the choice of either bearing up to make a junction with Monk and the others before accepting battle or of grappling with Tromp at once, trusting to his admirals to arrive in time to win a victory. It was characteristic of Blake that he chose the bolder course.

The fighting began early in the afternoon and was close and furious from the outset. Again Blake’s ship was compelled to engage several Dutch, including Tromp’s flagship. De Ruyter, the brilliant lieutenant of Tromp, attempted to cut Blake off from his supports on the north, and Evertsen steered between Blake and Penn’s squadron on the south. Blake’s dozen ships might well have been surrounded and taken if his admirals had not known their business. Penn tacked right through Evertsen’s squadron to come to the side of Blake, and Lawson foiled de Ruyter by bearing away till he had enough southing to tack in the wake of Penn and fall upon Tromp’s rear. Evertsen then attempted to get between Monk and the rest of the fleet and two hours after the fight in the center began Monk also was engaged. When the lee vessels of the “red” or center squadron came on the scene about four o’clock, they threatened to weather the Dutch and put them between two fires. To avoid this and to protect his convoy, Tromp tacked his whole fleet together—an exceedingly difficult maneuver under the circumstances—and drew off to windward. Darkness stopped the fighting for that day. All night the two fleets sailed eastward watching each other’s lights, and hastily patching up damages.

Morning discovered them off the Isle of Wight, with the English on the north side of the Channel. As Tromp’s chief business was to save his convoy and as the English force was now united, he took a defensive position. He formed his own ships in a long crescent, with the outward curve toward his enemy, and in the lee of this line he placed his convoy. The wind was so light that the English were unable to attack until late. The fighting, though energetic, had not proved decisive when darkness fell.

The following day, the 20th, brought a fresh wind that enabled the English to overhaul the Dutch, who could not move faster than the heavily laden merchantmen, and force a close action. Blake tried to cut off Tromp from the north so as to block his road home. Vice Admiral Penn, leading the van, broke through the Dutch battle line and fell upon the convoy, but Blake was unable to reach far enough to head off his adversary before he rounded Cape Gris Nez under cover of darkness and found anchorage in Calais roads. That night, favored by the tide and thick weather, Tromp succeeded in carrying off the greater part of his convoy unobserved. Nevertheless he had left in Blake’s hand some fifty merchantmen and a number of men of war variously estimated from five to eighteen. At the same time the English had suffered heavily in men and ships. On Blake’s flagship alone it is said that 100 men had been killed and Blake and his second in command, Deane, were both wounded, the former seriously.

The result of this three days’ action was to encourage the English to press the war with energy and take the offensive to the enemy’s own coast. English crews had shown that they could fight with a spirit fully equal to that of the Dutch, and English ships and weight of broadside, as de Ruyter frankly declared to his government, were decidedly superior. The fact that the shallow waters of the Dutch coast made necessary a lighter draft man of war than that of the English proved a serious handicap to the Dutch in all their conflicts with the British. Both fleets were so badly shot up by this prolonged battle that there was a lull in operations until May.

In that month Tromp suddenly arrived off Dover and bombarded the defenses. The English quickly took the sea to hunt him down. As Blake was still incapacitated by his wound, the command was given to Monk. The latter, with a fleet of over a hundred ships, brought Tromp to action on June 2 (1653) in what is known as the “Battle of the Gabbard” after a shoal near the mouth of the Thames, where the action began. Tromp was this time not burdened with a convoy but his fleet was smaller in numbers than Monk’s and, as he well knew, inferior in other elements of force. Accordingly, he adapted defensive tactics of a sort that was copied afterwards by the French as a fixed policy. He accepted battle to leeward, drawing off in a slanting line from his enemy with the idea of catching the English van as it advanced to the attack unsupported by the rest of the fleet, and crippling it so severely that the attack would not be pressed. As it turned out, a shift of the wind gave him the chance to fall heavily upon the English van, but a second shift gave back the weather gage to the English and the two fleets became fiercely engaged at close quarters. Blake, hearing the guns, left his sick bed and with his own available force of 18 ships sailed out to join battle. The sight of this fresh squadron flying Blake’s flag, turned the fortune of battle decisively. The Dutch escaped destruction only by finding safety in the shallows of the Flemish coast, where the English ships could not follow.

After this defeat the Dutch were almost at the end of their resources and sued for peace, but Cromwell’s ruthless demands amounted to a practical loss of independence, which even a bankrupt nation could not accept. Accordingly, every nerve was strained to build a fleet that might yet beat the English. The latter, for their part, were equally determined not to lose the fruits of their hard won victories. Since Blake’s active share in the battle of the Gabbard aggravated his wound so severely that he was carried ashore more nearly dead than alive, Monk retained actual command.

Monk attempted to maintain a close blockade of the Dutch coast and to prevent a junction between Tromp’s main fleet at Flushing and a force of thirty ships at Amsterdam. In this, however, he was outgeneraled by Tromp, who succeeded in taking the sea with the greatest of all Dutch fleets, 120 men of war. The English and the Dutch speedily clashed in the last, and perhaps the most furiously contested, battle of the war, the “Battle of Scheveningen.” The action began at six in the morning of July 30, 1653. Tromp had the weather gage, but Monk, instead of awaiting his onslaught, tacked towards him and actually cut through the Dutch line. Tromp countered by tacking also, in order to keep his windward position, and this maneuver was repeated three times by Tromp and Monk, and the two great fleets sailed in great zigzag courses down the Dutch coast a distance of forty miles, with bitter fighting going on at close range between the two lines. Early in the action the renowned Tromp was killed, but his flag was kept flying and there was no flinching on the part of his admirals. About one o’clock a shift of the wind gave the weather gage to the English. Some of the Dutch captains then showed the white feather and tried to escape. This compelled the retirement of DeWith, who had succeeded to the command, and who, as he retreated, fired on his own fugitives as well as on the English. As usual in those battles with the Dutch, the English had been forced to pay a high price for their victory. Their fleet was so shattered that they were obliged to lift the blockade and return home to refit. But for the Dutch it was the last effort. Again they sued for peace. Cromwell drove a hard bargain; he insisted on every claim England had ever made against the Netherlands before the war, but on this occasion he agreed to leave Holland her independence.

Thus in less than two years the First Dutch War came to an end. In the words of Mr. Hannay, the English historian, its “importance as an epoch in the history of the English Navy can hardly be exaggerated. Though short, for it lasted barely twenty-two months, it was singularly fierce and full of battles. Yet its interest is not derived mainly from the mere amount of fighting but from the character of it. This was the first of our naval wars conducted by steady, continuous, coherent campaigns. Hitherto our operations on the sea had been of the nature of adventures by single ships and small squadrons, with here and there a great expedition sent out to capture some particular port or island.”

As to the intensity of the fighting, it is worth noting that in this short period six great battles took place between fleets numbering as a rule from 70 to 120 ships on a side. By comparison it may be remarked that at Trafalgar the total British force numbered 27 ships of the line and the Allies, 33. Nor were the men of war of Blake and Tromp the small types of an earlier day. In 1652 the ship of the line had become the unit of the fleet as truly as it was in 1805. It is true that Blake’s ships were not the equal of Nelson’s huge “first rates,” because the “two-decker” was then the most powerful type. The first three-decker in the English navy was launched in the year of Blake’s death, 1657. The fact remains, however, that these fleet actions of the Dutch Wars took place on a scale unmatched by any of the far better known engagements of the 18th or early 19th century.

A curious naval weapon survived from the day when Howard drove Medina Sidonia from Calais roads, the fireship, or “brander.” This was used by both English and Dutch. Its usefulness, of course, was confined to the side that held the windward position, and even an opponent to leeward could usually, if he kept his head, send out boats to grapple and tow the brander out of harm’s way. In the battle of Scheveningen, however, Dutch fireships cost the English two fine ships, together with a Dutch prize, and very nearly destroyed the old flagship of Blake, the Triumph. She was saved only by the extraordinary exertions of her captain, who received mortal injury from the flames he fought so courageously.

This First Dutch War is interesting in what it reveals of the advance in tactics. Tromp well deserves his title as the “Father of Naval Tactics,” and he undoubtedly taught Blake and Monk a good deal by the rough schooling of battle, but they proved apt pupils. From even the brief summary of these great battles just given, it is evident that Dutch and English did not fight each other in helter skelter fashion. In fact, there is revealed a great advance in coördination over the work of the English in the campaign of the Armada. These fleets worked as units. This does not mean that they were not divided into squadrons. A force of 100 ships of the line required division and subdivision, and considerable freedom of movement was left to division and squadron commanders under the general direction of the commander in chief, but they were all working consciously together. Just as at Trafalgar Nelson formed his fleet in two lines (originally planned as three) and allowed his second in command a free hand in carrying out the task assigned him, so Tromp and Blake operated their fleets in squadrons—Tromp usually had five—and expected of their subordinates responsibility and initiative. All this is in striking contrast with the practice that paralyzed tactics in the latter 17th and 18th centuries, which sacrificed everything to a rigid line of battle in column ahead, and required every movement to emanate from the commander in chief.

Although details about the great battles of the First Dutch War are scanty, there is enough recorded to show that both sides used the line ahead as the normal battle line. It is equally clear, however, that they repeatedly broke through each other’s lines and aimed at concentration, or destroying in detail. These two related principles, which had to be rediscovered toward the end of the 18th century, were practiced by Tromp, de Ruyter, and Blake. Their work has not the advantage of being as near our day as the easy, one-sided victories over the demoralized French navy in the Revolutionary and Napoleonic era, but the day may come when the British will regard the age of Blake as the naval epoch of which they have the most reason to be proud. Then England met the greatest seamen of the day led by one of the greatest admirals of history and won a bitterly fought contest by virtue of better ships and the spirit of Cromwell’s “Ironsides.”

4

This narrative is both brief and leaves some incredibly important details out. The English lost all of the battles in the Med and Indies and the Dutch were left in control in those places with little English resistence. In addition, Dutch privateering was much more destructive on English commerce globally than England’s efforts to cripple Dutch commerce. England was as bankrupt at the end of the conflict (if not more-so) than Holland. The merchant class pressured Cromwell throughout the war to end it or they would all be ruined. So the English were just as desirous to move to the peace table as the Dutch were.

Interesting, and thank you for your observations. We may note the source is called “A History of Sea Power,” which implies a somewhat restricted scope of these events.