Editor’s Note: The following comprises the eighth chapter of Sunshine and Storm in Rhodesia, by Frederick Courteney Selous (published 1896). All spelling in the original.

CHAPTER VIII

I will now again take up the thread of my own personal experiences. As will be remembered, I reached my homestead at 2 A.M. on Thursday, 26th March, and found everything as I had left it seventeen hours before. A mule cart carrying food supplies for my men was to have followed immediately behind us, but the men in charge lost the road, and the provisions did not turn up till late the next day.

On the following morning, just at daybreak, a native named Inshlupo, who had been in charge of a herd of over thirty head of cattle belonging to my Company, turned up and informed me that on the previous evening the headman of a small Matabele kraal, situated in the broken ground just below the Malungwani Hills, had paid him a visit, accompanied by several armed men, and taken off all the cattle.

On the receipt of this news I had the horses saddled up at once, as, it being still so early, I had little doubt that, if no time was lost, we should find the stolen cattle still in the kraal to which they had been taken the previous evening. Before moving, however, I said a few words to my men, telling them that my object in visiting Essexvale and other parts of the country with an armed force was twofold, namely, to endeavour by prompt action to strike terror into the hearts of some of the rebels before they had time to concentrate, and at the same time to reassure those who were content with the white man’s rule, but who, in the absence of any display of power on the part of the Government, might be led to believe that their only chance of safety from the vengeance of the Matabele lay in taking part with them in the rebellion. In conclusion, I told them that any Kafirs we might find with arms in their hands, who had left their kraals and gone off into the hills with stolen cattle, ought to be shot without question and without mercy, as they were every one of them more or less responsible for the cruel murders of white men that had already been committed.

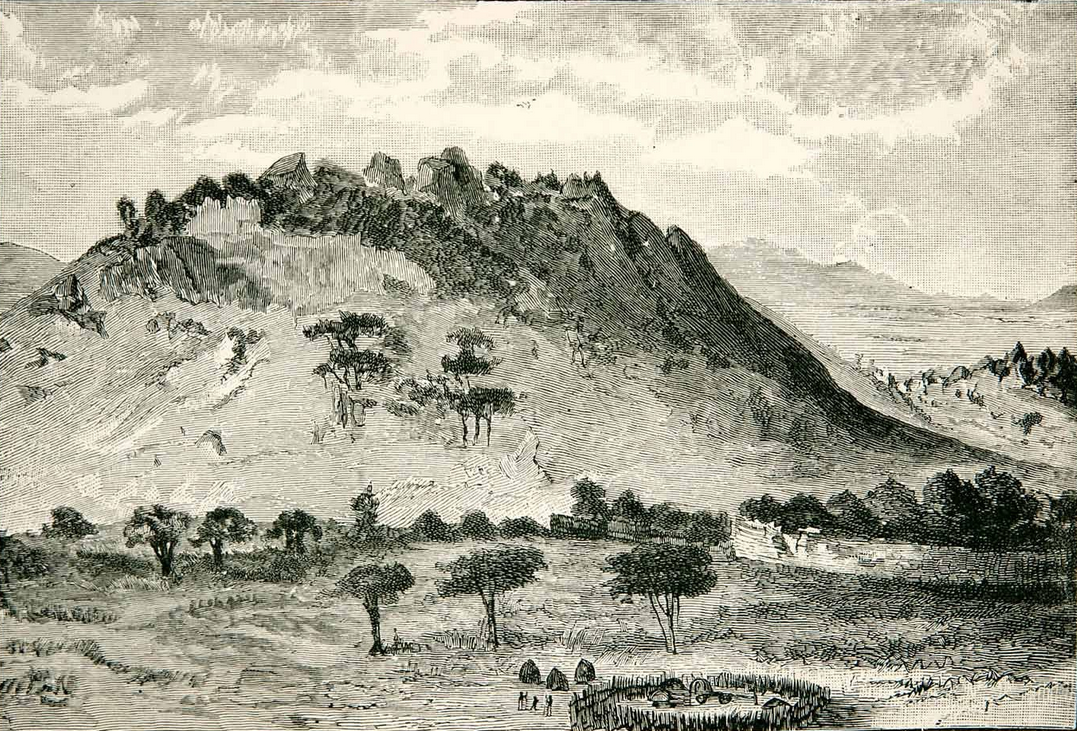

Under the guidance of Inshlupo we reached the neighbourhood of the kraal where I hoped to find my Company’s cattle before the sun was an hour higher. Here I halted my men, and sent half of them round under the shelter of the bush to a certain point where they were to show themselves, that being the signal for a simultaneous advance as rapidly as possible on the kraal from both sides. However, although we found all the cattle still in the kraal, there were no men there, and in fact no one but a Matabele woman, the wife of the headman, and several children. The woman would offer no explanation of the undeniable fact that my Company’s cattle were in her husband’s kraal, and would give no information concerning his whereabouts, so, after driving out the stolen cattle, I had the whole place burnt, first allowing the woman to remove all her private effects. When this had been done, I sent the recaptured cattle back to the homestead, in charge of two of Inshlupo’s boys, and then proceeded straight into the Malungwani Hills, in the hope of coming across some of the rebels who had gone off with the first lot of my Company’s cattle that had been stolen on the previous Tuesday night.

As we proceeded, the hills became thickly wooded, and in the valleys between them we found the spoor of a good many cattle that had passed during the last two days, although we saw no fresh tracks.

About nine o’clock I gave the order to off-saddle in a little grassy hollow, after first placing sentries all round to guard against any sudden attack, for we were now, of course, in the enemy’s country. After an hour’s rest the horses were just being caught when one of the sentries reported that a herd of cattle was being driven up a valley at the foot of a high ridge to our left. I at once went up to have a look myself, but by this time the cattle were out of sight. However, I carefully examined the ground, and saw that by following another valley running parallel to the one in which the cattle had been seen, and then ascending the steep ridge at its head, we should in all probability drop right on to the rebels in charge of them.

And this is exactly what happened, as upon cresting the ridge we found that both Kafirs and cattle were immediately below us. Some of the former were driving the cattle, but most of them were in the bush ahead. We at once opened fire on them, which they made no attempt to return. Indeed, taken by surprise as they were, and having so much the worse of the position, and, moreover, not being in any force, they could scarcely be expected to do anything else but run for it. And run they did, throwing down almost everything they were carrying, and abandoning the cattle. I saw one man throw a gun away, probably fearing lest he should be caught with it in his possession, but most of them were, I think, only armed with assegais. We chased them up and down several hills, and expended a lot of ammunition on them, but did them I am afraid very little damage, as the hills were all thickly wooded, and our horses were not able to climb up and down them any faster than the light-footed savages we were pursuing. In the second valley we found another herd of cattle, but could see no Kafirs near them, and I think they must have heard the firing, and run off before we came in sight. Altogether we captured over 150 head of cattle, every one of which had been taken from white men, a large number having Mr. Colenbrander’s brand on them.

I have stated plainly that we fired on these Kafirs at sight, and that although they offered no resistance, but ran away as hard as they could, we chased them and kept on firing at them as long as we could see them, and this action may possibly be cited as an example of the brutality and inhumanity of the Englishmen in Rhodesia. The fact that the Kafirs whom we sought to destroy—with as little compunction as though they were a pack of wild dogs—were taking part in a rebellion which had just been inaugurated by a series of the foulest murders it is possible to conceive, and the ultimate object of which was evidently to stamp out the white man throughout the land, will, of course, be entirely lost sight of or quietly ignored. In fact, I should not be at all surprised to see it stated that the rebellion was caused by the inhuman behaviour of the white men in Rhodesia, who, it will be said, were in the habit of shooting down the poor, meek, inoffensive Matabele.

The Kafirs upon whom we fired were, of course, caught red-handed, driving off a herd of cattle, every animal in which had been taken from a white man, and we afterwards learnt that they were the very men who had stopped Mr. Meikle’s waggon two days before on the Insiza road (some eight or ten miles distant), murdered the colonial boys in charge of it, and assegaied the sixteen donkeys harnessed to it.

For breaking out into rebellion against the white man’s rule, and for taking all the cattle in the country, I should have borne them no great animosity, especially as the great majority of these cattle had once belonged to their king or to them personally. Being a representative of the race that had conquered them, I should, of course, have lent the services of my rifle to help to quell the rebellion no matter what form it had taken; but had it not been accompanied by the cruel murders of white women and children, I should not have been animated by the same vengeful feelings as now possessed me, as well as every other white man in Matabeleland.

“But,” the kind-hearted, untravelled humanitarian may say, “such incidents are the necessary accompaniments of a native rebellion against Europeans, and ought not therefore to excite any greater surprise or indignation in your colonist than they do in myself; and, moreover, given that you admit that, looking at things from their point of view, the Matabele were justified in rebelling against the white man’s rule, go further and acknowledge that the white men were wrong in ever attempting the colonisation of any of the territories between the Limpopo and the Zambesi, since it was the occupation of Mashunaland in 1890 that led to the various disagreements between Lo Bengula and the Chartered Company which culminated in the invasion and conquest of Matabeleland in 1893.”

To this proposition I would answer that the whole question of the colonisation by Europeans of countries previously inhabited by savage tribes must be looked upon from a broad point of view, and be judged by its final results as compared with the primitive conditions it has superseded. Two hundred years ago, the Eastern States of North America were inhabited by savage tribes who, by incessant internecine war and the practice of many abominable customs, constantly deluged the whole land with blood. Now the noble red man has disappeared from those territories—has been exterminated by the more intelligent white man—and in place of a cruel, hopeless savagery there has arisen a civilisation whose ideals are surely higher than those of the displaced barbarism. In like manner, before Van Kiebek landed at the Cape of Good Hope, the whole of South Africa was in the hands of savages, a people, be it noted, who were not living in Arcadian simplicity, a peaceful happy race amongst whom crime and misery were unknown quantities, but on the contrary, who were a prey to cruel superstitions, involving a constant sacrifice of innocent life, and who were, moreover, continually exposed to all the horrors of intertribal wars. Now an orderly civilisation has been established over a large area of this once completely savage country, and no one but an ignorant fanatic would, I think, assert that its present condition is not preferable from a humanitarian point of view to its former barbarism. Well, the present state of Matabeleland is one of transition. Its past history—and this fact ought not to be ignored by the impartial critic of what is happening there to-day—has been one of ceaseless cruelty and bloodshed. But in time a civilisation will have been built up in that blood-stained land, as orderly and humane as that which has been established—in place of a parallel barbarism—in the older States of South Africa.

Yet, just as in the establishment of the white man’s supremacy in the Cape Colony, the aboriginal black races have either been displaced or reduced to a state of submission to the white man’s rule at the cost of much blood and injustice to the black man, so also will it be in Matabeleland, and so must it ever be in any country where the European comes into contact with native races, and where at the same time the climate is such that the more highly organised and intelligent race can live and thrive, as it can do in Matabeleland; whilst the presence of valuable minerals or anything else that excites the greed of the stronger race will naturally hasten the process. Therefore Matabeleland is doomed by what seems a law of nature to be ruled by the white man, and the black man must go, or conform to the white man’s laws, or die in resisting them. It seems a hard and cruel fate for the black man, but it is a destiny which the broadest philanthropy cannot avert, whilst the British colonist is but the irresponsible atom employed in carrying out a preordained law—the law which has ruled upon this planet ever since, in the far-off misty depths of time, organic life was first evolved upon the earth—the inexorable law which Darwin has aptly termed the “Survival of the Fittest.”

Now there may be those who maintain that the aboriginal savagery of the Red Indians in the Eastern States of North America, or of the Kafirs in the Cape Colony, was a preferable state of things to the imperfect civilisations which have superseded them. To such I have no reply. “Chacun à son goût.” Only I would ask them to endeavour to make themselves as well acquainted as possible with the subject under discussion, either by actual travel or by reading, and I would beg them not to accept too readily the assertions constantly made without any regard to truth or honesty by the newspaper opponents of British colonisation, which are broadly to the effect that no savagery exists in Africa except that practised on the blacks by Europeans.