Editor’s Note: The following comprises the fifth chapter of Sunshine and Storm in Rhodesia, by Frederick Courteney Selous (published 1896). All spelling in the original.

CHAPTER V

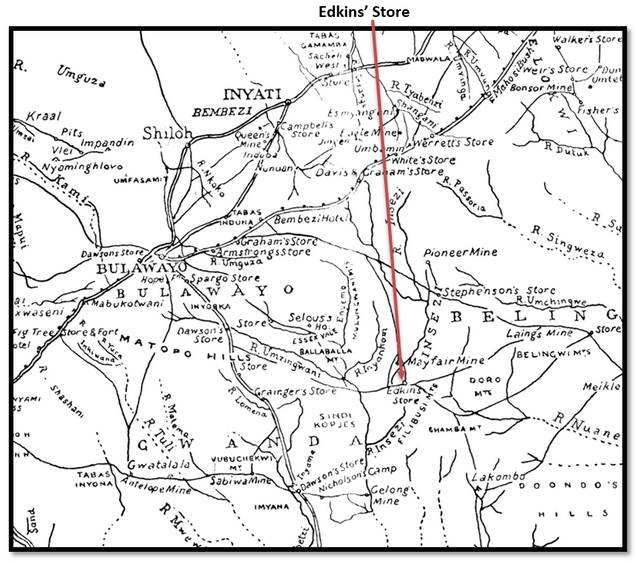

Not far from the once large military kraal of Gorshlwayo, near the southern border of Essexvale, was a trading station known as Edkins’ store. In the neighbourhood were several mining camps and the residence of a native commissioner, and it is here probably that the first murders of Europeans were committed during the present native rising.

At any rate some time on Monday, 23rd March, seven white men, two colonial boys and a coolie cook were murdered there. Among the murdered men was Mr. Bentley, the native commissioner, who was shot or stabbed from behind, whilst sitting in his hut writing—the date above the last words he ever wrote being 23rd March. Mr. Edkins and three other white men, together with their two colonial servants and the coolie cook, were killed in and round the store, whilst Messrs. Ivers and Ottens were killed, the former near the Celtic mining camp, and the latter about half-way between the camp and the store, from which it was distant about a mile and a half. The corpses of these poor fellows were found by Colonel Spreckley’s relief party four days subsequent to the massacre. A colonial native was also discovered still living, though terribly injured. He had evidently been left for dead by the Matabele, and besides the wounds which they had inflicted on him in order to kill him, they had slit his mouth open from ear to ear. It was not thought that this man could possibly live, but his wounds were dressed, and food given him, and, wonderful to relate, he eventually made his way to Bulawayo, where, thanks to the skilful treatment and kind nursing he received in the hospital there, he in time recovered from his injuries.

He was able to give evidence concerning the murders, which he said were committed suddenly and without warning by native policemen, aided by natives from the surrounding kraals under two brothers of Lo Bengula, Maschlaschlin and Umfaizella, who, with Umlugulu, Gwibu, Umfondisi, and other members of the king’s family, were the chief instigators of the rebellion; and this being so, no peace can be made that will satisfy the colonists until all the members of the late king’s family, as well as every Induna and every native policeman who it can be proved took part in the murders which marked the outbreak of the rebellion, have been either hanged or shot.

This may seem a big order to some people—who, however, do not probably contemplate residing on a lonely farm in Rhodesia—but it is necessary for the future safety of the country.

The bodies of Ottens and Bentley had been mutilated, and dry grass had been heaped up and burnt over the faces of all the dead, possibly with the idea of destroying their identity.

Almost simultaneously with the murders at Edkins’ store, or at any rate on the same day, the massacre of the whites was commenced in the Insiza district, the first sufferers being probably the Cunningham family, who were living on a farm near the Insiza river. These poor people seem to have been attacked early in the afternoon, as when their homestead was visited on the following day by Messrs. Liebert and Fynn, the remains of the mid-day meal were still on the table, whilst old Mr. Cunningham seemed to have been murdered whilst reclining on a couch reading a newspaper. Here is the sworn deposition of Mr. Fynn, the assistant native commissioner for the Insiza district, as to the finding of the bodies.

Herbert Pomeroy Fynn’s sworn statement:—

“I am an assistant native commissioner for the Insiza district. I accompanied last witness—Mr. Liebert—and Orpen to Cunningham’s farm on Tuesday morning, 24th March. On arrival there I saw eight dead bodies lying on the ground about twenty yards from the homestead. We made a cursory examination and saw that the deceased persons had been murdered by means of knob-kerries and battle-axes, or similar weapons. The ground was covered with native footprints, and there were broken knob-kerries lying about. I identified among the dead bodies those of Mr. Cunningham senior, Mrs. Cunningham, two Miss Cunninghams, Master Cunningham, and three children whom I identified as the grandchildren of Mr. Cunningham senior. The deceased persons appeared to have been killed inside the house and afterwards dragged out and thrown outside in the position in which we found them. From the fact that all the native kraals in the vicinity were quite deserted, I have absolutely no doubt that the persons who killed the deceased were Matabele natives. Young Cunningham, aged about fourteen years, was still alive when we arrived, but unconscious, and died immediately after our arrival.”

Such is the bald account of the discovery of the battered and bloody remains of this unfortunate family, which, alas! was not the only one suddenly blotted out of existence, root and branch, during the first terrible days of the Matabele rebellion. The hideous barbarity of these murders, and the feeling of intense exasperation they would be likely to excite amongst the surviving settlers, seem to have been somewhat underrated in England; whilst for obvious reasons they have been carefully kept out of sight by those dishonest speakers who recently endeavoured to excite public opinion against the white population of Rhodesia. You can respect an honest enemy even if you can’t like him; but when a fanatic endeavours to support either his or her theories by the suppression of truth, he or she becomes contemptible.

But we are thankful for the sympathy of that most determined enemy of everything Rhodesian—except the noble savages who therein dwell—Mr. Labouchere, who has professed himself “sorry for the women and children who have been killed.” Sorry—only sorry! Wonderful indeed is the calm serenity of soul that enables that noble nature to view all mundane affairs from the same cold, passionless plane, whether it be the cruel murder of an English settler’s wife and family in Rhodesia, or an accident to the wheel of a friend’s bicycle in Hyde Park! But the men who have looked upon the corpses of the murdered ones, who have seen the shattered skulls of their countrywomen, the long grey locks of the aged and the sunny curls of the girls and little children all alike dabbled in their blood, are something more than sorry; indignation mingles with their sorrow, and they are determined to exact such punishment for the crimes committed, as shall preclude as far as possible their recurrence in the future.

At a distance of a few miles from the Cunninghams’ farm was a mining property belonging to the Nellie Reef Development Company, where work was being carried on under the superintendence of Mr. Thomas Maddocks, the manager of the Nellie Reef Mine. At about a quarter to six on the evening of Monday, 23rd March, that is probably some four hours after the murder of the Cunningham family, Mr. Maddocks and two miners, Messrs. Hocking and Hosking, were sitting smoking outside their huts just before dinner, when some fifteen natives came up armed with knob-kerries and battle-axes. The man who appeared to be their leader spoke to Mr. Maddocks and said that he and his companions had been sent by Mr. Fynn, the native commissioner, to work, and on being asked if he had a letter from that gentleman, called to some more natives who were standing not far off. What followed I will tell in the words of Mr. John Hosking, who, in his sworn statement regarding the death of Mr. Maddocks, deposes as follows:—

“The call was answered by a shout of ‘Tchaia,’ ‘strike.’ A number of natives joined those who were with us, and the leader then struck deceased on the head with a knob-kerry. I immediately retired into my hut for my revolver. When I came back three natives were hitting Hocking with kerries and axes. I fired a shot and dropped one man, and just as I had fired my second shot, I received a blow on the head causing the mark I now show. Hocking then managed to get into the hut, whereupon the natives cleared off; Hocking and I then went to Maddocks, but found him dead. We retired into an iron store, at which the natives fired a shot. The bullet passed inside through the iron, which caused us to retire again to the hut.” By this time it was growing dusk, so the two wounded miners, fearing that the natives would soon return and fire the hut, crept out, and getting into the long grass, made their escape to Cumming’s store, three miles from Maddocks’ camp, where about twenty men had already collected, many of whom, however, were unarmed. A laager was at once formed, and Mr. Cumming and another rode into Bulawayo for assistance. They first, however, warned several miners and farmers living in the neighbourhood, that the natives had risen, thus saving the lives of these people, as they all got safely to the laager and ultimately escaped to Bulawayo, whereas but for this timely warning they would most certainly have been murdered.

Mr. Cumming and his companion reached Bulawayo on Tuesday morning, and at once reported themselves to Mr. Duncan, the Administrator.

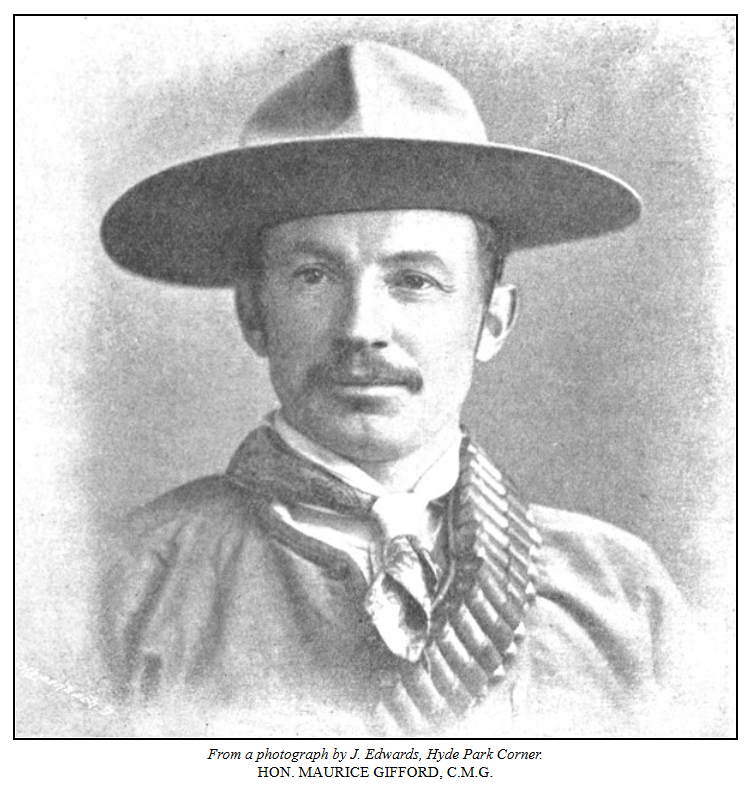

At this time no organised force existed in the country, with the exception of the few men of the Matabele Mounted Police under Captain Southey; and there were only some 370 rifles in the Government stores. However, no difficulty was experienced in getting men together who were ready to proceed at once to the relief of their countrymen and countrywomen; and, as I have already narrated, three small corps under experienced leaders were despatched to various outlying districts within a few hours of the time when the first alarm was given. The Hon. Maurice Gifford, as energetic as he is brave, got off that same evening with about forty men, including Captain Southey and twelve of his Mounted Police; his object being the relief of the men who had laagered up at Cumming’s store. The first sign of the rising seen by this party was near Woodford’s store, about fourteen miles beyond Thaba Induna, or twenty-six from Bulawayo. Here an abandoned waggon was found standing in the road, the sixteen donkeys that had been harnessed to it lying all of a heap dead. They had for the most part been stabbed to death with assegais, but some had been shot. Nothing on the waggon had been touched, though it was loaded with flour, whisky, etc. No trace of those who had been in charge of the waggon could be discovered, but it has been subsequently ascertained that they were murdered in the bush some little distance away. They were colonial boys taking down a load of stores to the Insiza district. Soon after this derelict waggon had been passed, three colonial boys were met making their way to Bulawayo, one armed with a rifle and another with a revolver. They reported to Mr. Gifford that the rising was general in the Insiza district, and said that a Dr. and Mrs. Langford had been killed on the previous day—Wednesday, 25th March—near Rixon’s farm; but that Mr. Rixon, the Blicks, and others in the district had escaped to the laager at Cumming’s store. They also told Mr. Gifford that they had seen several troops of cattle being driven by armed Matabele towards the Malungwani and Matopo Hills. On meeting Mr. Gifford these “boys” turned back and accompanied him to the Insiza, and did good service in the subsequent fight, in which one of them was wounded.

On Thursday night the relief party reached Cumming’s store, where they found about thirty men in laager. Of these, however, a large proportion were unarmed, so that Mr. Gifford had only about fifty rifles at his command altogether. The night passed off quietly, but at about 5 A.M., just before daylight on Friday morning, a most determined attack was made on the position by a large party of Matabele, who did not finally retreat until they had suffered heavy loss from the steady fire of the white men. The natives came on with the utmost fearlessness, as may be inferred from the fact that one was killed with his hands on the window-sill of the store, whilst six others lay dead close round; and it was afterwards ascertained that their total loss was twenty-five.

On the side of the whites, Sergt.-Major O’Leary of the Matabele Mounted Police was killed, as well as an educated American negro, a servant of Mr. Wrey’s, whilst six white men were wounded. As soon as the attack had been completely beaten off, the waggons were inspanned, and the beleaguered white men broke up their laager and commenced their retreat to Bulawayo.

The first portion of the road to be travelled led amongst broken wooded hills, through which it was expected they would have to fight their way; but although the Matabele once gathered on the top of a neighbouring hill, and seemed about to attack, they did not do so, and thus allowed the whites to get out into the open country, where they were comparatively safe, without further molestation.

I think it will not be out of place to here reproduce, with the kind permission of Mr. Maurice Gifford, two letters written by him on the night after the fight, of which I happen to have copies, as they cannot fail, I think, to interest my readers.