Editor’s Note: The following comprises the twenty-second chapter of Sunshine and Storm in Rhodesia, by Frederick Courteney Selous (published 1896). All spelling in the original.

CHAPTER XXII

Owing to various circumstances, it was found impossible to get the column off for the Tchangani on the following morning, and the start was not actually made until Monday, 11th May. This column, the largest yet sent out from Bulawayo, was despatched with the object of opening the road to the Tchangani river, where it was hoped that the relief force from Salisbury under Colonel Beal, with which was Mr. Cecil Rhodes, would be met, when the future movements of the combined columns would be determined according to circumstances.

The composition of the force was as follows: Artillery, four officers and thirty-four men under Captain Biscoe; Grey’s Scouts, four officers and forty men under Captain Grey; Africander Corps, three officers and fifty-nine men under Commandant Van Rensberg and Captain Van Niekerk; A troop (Gifford’s Horse) two officers and nineteen men; B troop (Gifford’s Horse) two officers and twenty men—the combined troops under Captain Fynn; F troop, one officer and twenty men under Lieutenant H. Lamb; four officers and 100 dismounted men under Captain Selous, consisting of detachments from H, C, D, K, and L troops, under Captains Mainwaring and Reid, and Lieutenants Holland and Hyden; also four engineers; making altogether 312 Europeans, supported by 150 of Colenbrander’s Colonial Boys under Captain Windley, and 100 Friendly Matabele under Chief Native Commissioner Taylor. Also one seven-pounder, one 2·5 gun, one Hotchkiss, one Nordenfeldt, one Maxim; fourteen mule waggons carrying provisions, kit, and ammunition, and one ambulance waggon.

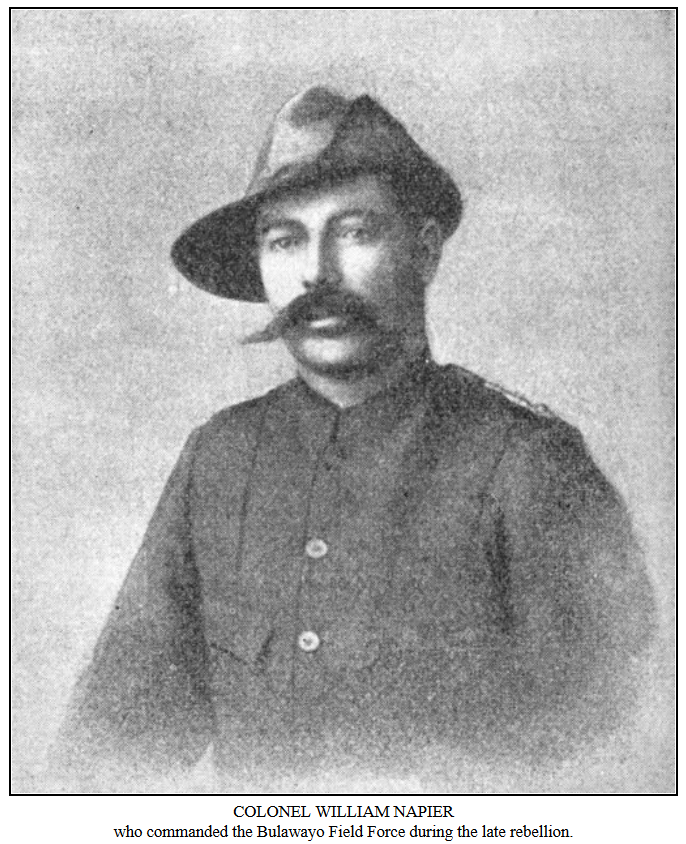

Of this force Colonel Napier was in command; Colonel Spreckley, second in command; Captain Llewellyn, staff orderly officer; Captain Howard Brown, staff officer; Captain Bradley, remount officer; Captain Molyneux, adjutant; Captain Wrey, heliograph officer; Captain Purssell, quartermaster; Dr. Levy, medical officer, with Lieutenants Little, Dollar, and Burnham as gallopers; whilst Captain the Honourable C. J. White and Mr. A. Rhodes also accompanied the expedition unattached, making I believe a total force of forty-two officers and 613 men.

With the column was one of two colonial natives who had been despatched on horseback a few days previously to try and carry a message through to Gwelo. They saw no signs of the enemy until after they had passed Mr. Stewart’s farm, but near the Tekwe river they rode into the middle of a Matabele impi, in the middle of the night, which was watching the road and had no fires burning. They were immediately attacked, and the boy who got back to Bulawayo had his horse killed under him almost immediately, and received an assegai-wound in the arm. However, in the darkness he managed to elude his enemies, and made his way back to town. His companion neither reached Gwelo nor ever returned to Bulawayo, but he apparently galloped through his assailants at the Tekwe, only to be again waylaid, and this time killed, at the Tchangani, where his corpse was discovered a few days later lying in the road by Colonel Beal’s column.

To quote the words of the correspondent with the column representing the Bulawayo Chronicle: “To the martial strains of the town band, on Monday, 11th May, the column under Colonel Napier left the citadel, and boldly started forth into the country lately taken from us by the Matabele. Within two hours our men had crossed from British territory into the Matabele country—to wit, the Umguza brooklet.”

Arrived at the Umguza, it was found that we could not proceed until certain stores, which had been left behind in Bulawayo, reached us; and as these did not come to hand until the following morning, we did not again make a move until shortly before noon on Tuesday. For some miles our route lay through perfectly open country, but on getting abreast of Thaba Induna we came to a strip of thorn bush through which the road passes. Here a halt was made, whilst Colonel Spreckley went forward with Grey’s Scouts to see if the bush was clear of Kafirs. He soon sent a messenger back reporting that the enemy were just in front of him, so Colonel Napier asked me to go on and obtain further particulars before he advanced with the whole column.

I found Colonel Spreckley about 600 yards in advance, the bush between where he had halted his men and the main body being much less dense than I had imagined, whilst in front of him the country was very open indeed. However, the grass was three or four feet high, and as some Kafirs had been seen on the rise only a few hundred yards ahead, it was impossible to tell how many of them there might be there. Colonel Spreckley therefore wanted some men on foot to be sent forward to assist the Scouts in driving the Kafirs out of the long grass.

I at once galloped back to the column, and was ordered to go forward again with two of the three troops of infantry under my command, Colonel Napier bringing on the remainder of the force behind us. As soon as my footmen reached the advance guard, we all spread out in skirmishing order and went forwards as rapidly as possible. The Kafirs, however, who had been seen in the long grass could only have been a few scouts, who, on seeing the mounted men, had retired on the main body, for until we came within a mile of the little pyramidal hill which stands by itself about a mile to the south of the low flat-topped hill known as Thaba Induna, we never saw a sign of the enemy.

Then, however, standing as we were on the crest of a rise, from which the ground sloped off into a broad valley which lay between us and the aforesaid hill, we suddenly came in sight of a considerable number of the rebels. A detachment of them was on the hill itself, whilst considerable numbers were scattered over the open ground below it. Altogether some hundreds of them must have been in sight. Between the single hill and the wooded slopes of Thaba Induna itself there is a space of perfectly open ground over a mile in breadth, and it certainly looked to the eye of an old hunter, accustomed in the pursuit of game to measure distances and take in at a glance the details of the ground before him, that, had the whole of the mounted men with the column at this juncture galloped as hard as they could go to the point of Thaba Induna, and then swept round at the back of the single hill, a large number of the rebels would have been cut off from the bush and killed in the open ground.

These tactics, however, were not adopted, and the natives got off scot free, for although a few shots were fired at them with a Maxim and seven-pounder at an unknown range, none were hit, and they all retreated into the thick bush to the north of Thaba Induna. Our column then advanced for another couple of miles, and laagered up near Graham’s store on the Kotki river.

On the following day the column remained in laager, and Colonel Napier took out a patrol, consisting of some 150 mounted men of Grey’s Scouts, Gifford’s Horse, and the Africander Corps, to ascertain if any of the rebels were still in our vicinity, and Captain Wrey accompanied the patrol in order to send some heliographic messages to Bulawayo.

Leaving the laager about 8 A.M., this force first returned about three miles along the road to Bulawayo, and when abreast of the single hill I have spoken of as having been occupied by the rebels on the previous day, turned to the right, and spreading out in skirmishing order advanced towards the hill, which was reached without a Kafir having been seen. Here Captain Wrey was left with his heliograph party, and a further advance was made towards the bush on the north-east corner of Thaba Induna, where were found the “scherms,” or military camps of the Matabele who had been seen on the previous day. These encampments appeared to have been evacuated early that morning, their occupants having probably moved off to join the impis which had retired from the vicinity of Bulawayo a short time before and taken up their quarters on the lower Umguza.

After these scherms had been burnt, a portion of the patrol was detached to the right, consisting of Grey’s Scouts, a section of the Africander Corps, and a small party of Gifford’s Horse, in all about eighty men. This detachment, after having advanced for a couple of miles through undulating country more or less covered with thorn bush, which in some places was fairly thick, came suddenly upon a small impi of 200 or 300 Kafirs, which I believe was a section of the Ingubu regiment.

These men had taken up a position along the crest of a rough stony ridge covered with bush, and when the approaching horsemen were still some four hundred yards distant they opened fire on them. Captain Grey immediately ordered his men to charge, which they did in extended order.

The sight of the long line of cavalry thundering down upon them seems to have turned the hearts of the savages to water, as their saying is, for after having fired a few more shots, they turned and ran, trusting to evade their enemies in the bush. A considerable number of them no doubt succeeded in doing so, but the chase was continued for a mile and a half, and when it was at last abandoned a long line of corpses marked the track where the whirlwind of the white man’s vengeance had swept along. Vae victis!—”woe to the conquered!”—woe indeed; for amongst the men who took part in the pursuit of the Kafirs, on this, to them, most fatal day, were many who, maddened by the loss of old chums foully slain in cold blood by the natives, were determined to use their opportunity to the utmost to inflict a heavy punishment for the crimes committed, while all were bent on exacting vengeance for the murders of the European women and children who had been hurried out of existence during the first days of the rebellion. Once broken, the Kafirs never made any attempt to rally, but ran as hard as they could, accepting death when overtaken without offering the slightest resistance; some indeed, when too tired to run any farther, walked doggedly forward with arms in their hands which they never attempted to use, and did not even turn their heads to look at the white men who were about to shoot them down. No quarter was either given or asked for, nor was any more mercy shown than had been lately granted by the Kafirs to the white women and children who had fallen into their power. This realistic picture may seem very horrible to all those who believe themselves to be superior beings to the cruel colonists of Rhodesia, but let them not forget the terrible provocation. I cannot dispute the horror of the picture; but I must confess that had I been with Captain Grey that day, I should have done my utmost to kill as many Kafirs as possible, and yet I think I can claim to be as humane a man as any of my critics who may feel inclined to consider such deeds cowardly and brutal and altogether unworthy of a civilised being.

This claim to humanity, coupled with the defence of savage deeds, may seem paradoxical, but the fact is, as I have said before, that in the smooth and easy course of ordinary civilised existence it is possible for a man to live a long life without ever becoming aware that somewhere deep down below the polished surface of conventionality there exists in him an ineradicable leaven of innate ferocity, which, although it may never show itself except under the most exceptional circumstances, must and ever will be there—the cruel instinct which, given sufficient provocation, prompts the meekest nature to kill his enemy—the instinct which forms the connecting link between the nature of man and that of the beast.

The horrors of a native insurrection—the murders and mutilations of white men, women, and children by savages—are perhaps better calculated than anything else to awake this slumbering fiend—the indestructible and imperishable inheritance which, through countless generations, has been handed down to the most highly civilised races of the present day from the savage animals or beings from whom or which modern science teaches us that they have been evolved. I have been told that Mr. Labouchere often jokingly says that we are all monkeys with our tails rubbed off, but with natures still very much akin to those of our simian relatives; and however that may be, we are certainly the descendants of the fierce and savage races by whom Northern and Central Europe was peopled in prehistoric times; and I am afraid that the saying of Napoleon, that “if you scratch a Russian you will find a Tartar,” may be extended to embrace the modern Briton or any other civilised people of Western Europe, none of whom it will be found necessary to scratch very deeply in order to discover the savage ancestors from whom they are descended.

On Wednesday afternoon subsequent to the dispersal of the natives, several kraals were burnt and a good deal of corn taken, which proved most valuable, being urgently required to keep the horses and mules in condition. About eighty head of cattle and some sheep and goats were also captured by Captain Fynn and Lieutenant Moffat. As during the time when the Kafirs were being chased by Grey’s Scouts and the Africanders, Captain Wrey had received a heliographic message from Earl Grey, requesting Colonel Napier not to proceed any farther until some waggons loaded with provisions for the Salisbury column, which had already left Bulawayo, had reached him, we spent another day in laager. The weather had now turned very cold, and on the Wednesday night heavy storms of rain had fallen all round us, though we had escaped with only a few drops; but on the following night, or rather very early on Friday morning, a soaking shower passed over us, and as we were lying out in the open, our blankets got wet through, rendering a very early start impossible; although, the convoy having reached us on Thursday night, the order had been given to have everything packed up ready to move by daylight.

However we got off by eight o’clock, and reached Lee’s store, distant twenty-four miles from Bulawayo, before mid-day. This store and hotel, noted as being the most comfortable on the whole road between the capital of Matabeleland and Salisbury, had, like every other building erected by a white man in this part of the country, been burnt down and as far as possible destroyed. After our horses and transport animals had had a couple of hours’ feeding, we proceeded on our way, and laagered up for the night on the site of the camp where Dr. Jameson was attacked on 1st November 1893 by the Imbezu and Ingubu regiments, during his memorable march from Mashunaland to Bulawayo.

On every side of this camp but that facing towards the west, the country consisted of open rolling downs, entirely devoid of bush for miles and miles. On the western face there was a space of open ground bounded at a distance of 500 or 600 yards by a strip of open thorn bush, and it was through this thorn bush that the Matabele warriors made their advance. Naturally, as they had to face the fire of several Maxims and other pieces of ordnance, they never got beyond the edge of the bush. It seems a marvel that they should have been foolish enough to advance as they did, but it was doubtless their ignorance of the impossibility of taking a laager by assault in the face even of a heavy rifle fire, let alone Maxim guns and other destructive toys of a similar character, which led them to expose themselves so vainly. But they learnt a lesson that day which has never been forgotten in Matabeleland, as the present campaign has shown.

The three following days were entirely without incident, as we never saw a sign of a Kafir, though every wayside hotel and store had been burnt to the ground. On Monday evening we laagered up at a spot a few miles short of the Pongo store, where it was known that some white men had been murdered. Mr. Burnham, the American scout, who had ridden on ahead in the afternoon, returned to the column at dusk from the store, with the news that a scouting party from the Salisbury contingent had been there also the same day, but had returned towards the Tchangani just before his own arrival.

On the following morning, Tuesday, 19th May, we reached the Pongo store early, having passed the coach which had been captured by the Kafirs some three miles on this side of it. As I have already stated, one wheel had been removed from the coach, and the pole had been sawn in two, whilst the contents of the mail-bags had been torn up and strewn over the ground in every direction. The sun-dried carcasses of the mules still lay all of a heap in their harness, just as they had fallen when they were assegaied some six weeks previously.

On reaching the store we found and buried the bodies of the two poor fellows (Hurlstone and Reddington) who had been murdered there just seven weeks previously, on Tuesday, 24th March. Both their skulls had been battered and chipped by heavy blows struck with knob-kerries and axes. The bodies had not been touched by any animal or Kafir since the day when the murders were committed, as their clothes and boots had not been removed, and the blankets thrown over them by the patrol party sent out from the Tchangani, two days after they were killed, were still covering them. The poor battered remains of what had so lately been two fine young Englishmen were reverently placed by their countrymen in a hastily-dug grave, and a prayer said over them by the good Catholic priest Father Barthélemy. The remains of the third white man murdered here were found at some little distance from the store.