Editor’s Note: The following comprises the twenty-first chapter of Sunshine and Storm in Rhodesia, by Frederick Courteney Selous (published 1896). All spelling in the original.

CHAPTER XXI

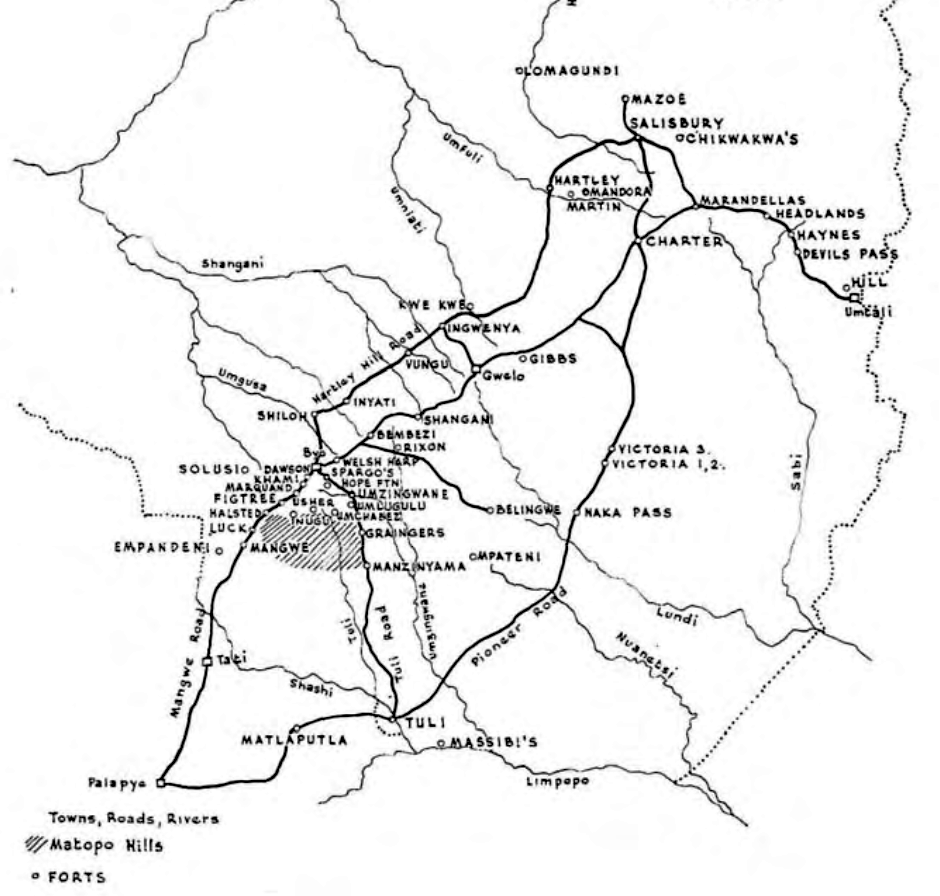

Lieutenant Grenfell having brought me a despatch on Monday evening, acquainting me that my presence was again required in Bulawayo, I handed over the command of Fort Marquand to him on the following morning, and rode in to town alone, meeting Lieutenant Parkin and a second escort which had been sent down to meet Earl Grey at the Khami river.

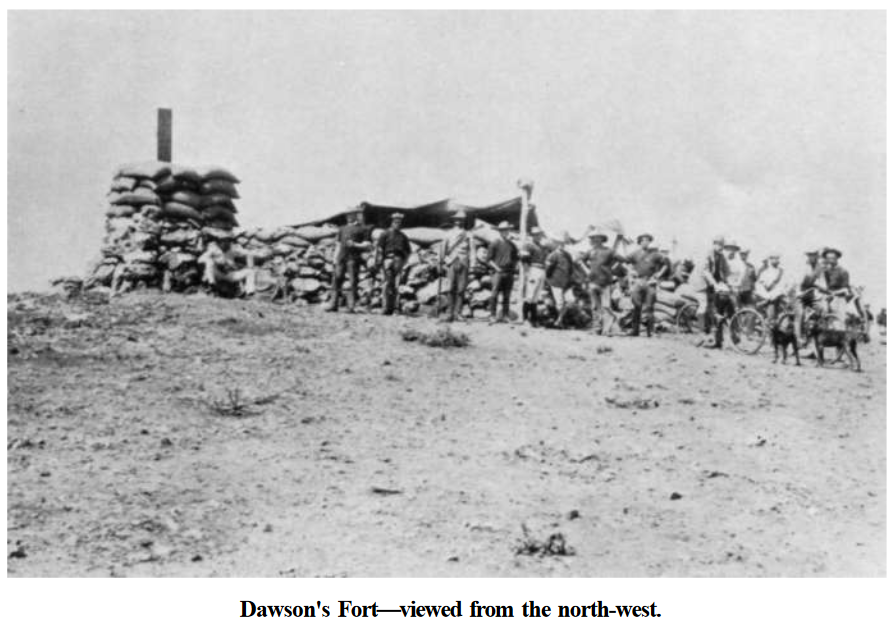

On arriving at Matabele, Wilson’s farm, six miles from Bulawayo, I found Captain Dawson with his troop and a lot of the “Friendlies” busily engaged in building a fort on a commanding position some four hundred yards away from the homestead and mule stables. With Captain Dawson, too, were my old friends, the well-known American Scouts Burnham and Ingram, and that very plucky English Scout Mr. Swinburne.

Although this detachment had only arrived here on the previous day, very considerable progress had already been made with the fort, which I was very pleased to find was being built at this place, as I had long advocated it, as also that another should be established at the Khami river, about half-way between Wilson’s farm and Fort Marquand.

This last link in the chain of forts between Bulawayo and Mangwe did not come into existence until some few days later, and only then could it be said that it was possible to have the road properly patrolled. Whilst resting my horse for half an hour at Dawson’s Fort I heard more details from him and the Scouts concerning the fight on the Umguza on the previous Saturday, which they considered to be the greatest reverse which the Matabele had yet suffered; or perhaps it would be fairer to say the only reverse, since, although, in every encounter their losses must have been very heavy compared with those of the whites, yet this was the first time that they had deemed it expedient to retreat from their position after the fight was over.

On reaching Bulawayo, however, I found that, although the impis which for the last ten days had been encamped along the Umguza in the immediate neighbourhood of the town had now moved some miles farther down the river, yet parties of them were still hanging about ready to murder any defenceless persons that they might be able to surprise, even on the very outskirts of the town, as was sufficiently proved by the fact that on the very morning of my arrival, that is on Tuesday, 28th April, several coolies had been murdered in their vegetable gardens just beyond the native location.

The following account of this affair I have taken over from the Matabele Times of 2nd May, by kind permission of the editor: “On their arrival in camp on Tuesday morning after night duty in the laager, the Mounted Police found a number of terrified coolies awaiting them, who informed them that they had been attacked by a large body of Matabele at their vegetable gardens, situated about two miles beyond the Matabele Mounted Police camp, and that eight of their number had been murdered. Some twelve or fifteen of the police promptly seized their rifles and bandoleers, and proceeded—on their own accord—in skirmishing order to the scene of the massacre, which they reached after a sharp twenty minutes’ walk. The enemy had disappeared from sight, but the tale of those coolies who had been fortunate enough to escape proved only too true. No less than eight coolies, including one young woman, were found lying foully murdered in different parts of the gardens, and every one, though pierced through over and over again with assegai stabs, was still warm. This proves that the enemy must have rushed down on the unprotected coolies in broad daylight.

“Shortly after the return of the police to camp, a couple of unarmed mounted men rode down to the gardens. They had not been there five minutes when they were fired upon from the adjacent kopjes, and they had to retire precipitately. This goes to prove that the enemy do not intend to give up their present position unless they are driven from it, and the sooner that is effected the better.” The following information was also given to the public committee. Sedan deposed: “I slept at my garden near the Butts last night with an American negro called Smith. Smith this morning before sunrise started to go to his own garden. I heard shots fired just after he left me. His Zambesi boy ran over and told me Smith had been killed. I saw about forty or fifty Kafirs. I saw one man with a gun, whilst the rest had assegais and sticks. I hid myself in a ditch, and saw the Kafirs in the gardens. I saw them kill Indians with the gun and the assegais. About half an hour later I saw a picket of four white men come to the gardens. I ran to the picket and came in to town. I was too frightened to say anything.” Ahchelrising deposed: “I slept in my garden and heard a shout from a lot of Indians early this morning that the Matabele were on to us. I ran away, and saw my brother Isree shot in front of me. I came to town and reported in the laager, and then went back to my garden. I saw the bodies of Goolab, Yitian, Venctayelee and his wife, Ramsamee and Chinantoniem. Smith’s Zambesi boy was also killed.”

On Tuesday night, 28th April, Earl Grey, accompanied by his secretary Mr. Benson, and General Digby Willoughby—who had been down to Mafeking in order to hurry forward the food supplies and relief forces—arrived in Bulawayo. The coach which brought the administrator and his party was escorted into town by Lieutenant Parkin and his men, whom I had met on their way down to meet it. They seem to have narrowly missed, or been missed by, a portion of Babian’s impi, which was reported on Wednesday morning to have crossed the road near the Khami river early on Tuesday night just after the coach had passed.

On the following morning, Wednesday, 29th April, an impi of several hundred Kafirs, in all likelihood a portion of Babian’s force, suddenly appeared on the rising ground about 1000 yards away from Dawson’s Fort. They were probably on their way to Wilson’s homestead with the intention of destroying and burning it down, but on seeing the fort manned by a number of white men, were evidently a bit taken aback, as they halted and held a council of war. They then spread out in skirmishing order, and getting down amongst the thorn trees in the river-bed below the house, advanced towards the fort as if about to attack it. However, after approaching to within 800 yards they thought better of it and withdrew, probably imagining that the place was defended with Maxim guns.

After retiring from the neighbourhood of the fort, they went down to Captain Molyneux’s farm, some two miles distant, and destroyed and burnt everything they could, even assegaiing the pigs, the carcasses of which animals they left untouched, as the Matabele of Zulu descent do not eat the flesh of the domestic pig, although they are very partial to that of both species of the wild swine found in Southern Africa, viz. the Wart Hog and the Bush Pig.

During my visit to Bulawayo it was at last decided to build a fort at the Khami river, and I was asked to take the work in hand forthwith. As only thirty men could be spared from Bulawayo, it was arranged that twenty more should be withdrawn from Fort Halsted, five miles beyond Fig Tree, and I requested that Lieutenant Howard, an old member of the Bechuanaland Border Police, who was at present with Captain Molyneux at Fig Tree, and who had done very good service in the first war during Major Forbes’ memorable retreat along the Tchangani river, should be placed in command of the two troops combined.

On Friday, 1st May, I left Bulawayo with Lieutenant Parkin and thirty men, accompanied by a mule waggon carrying kit, tools for fort-building, and provisions. We had first to take the waggon to Fort Marquand, there off-load it, and then send it on to Fort Halsted to bring back the twenty men from that place, who on their arrival at Mabukitwani could be at once despatched, together with the thirty under Lieutenant Parkin, to the Khami river, to commence building the fort there. This was all arranged by the Sunday evening, and everything got ready to proceed to the Khami river early the following morning. That evening, my old friend Cornelius Van Rooyen, commandant of the forces at Mangwe, accompanied by three of his men, arrived at my fort on his way to see Earl Grey, by whom he had been called to Bulawayo. He was, of course, an honoured guest with us, and we did all we could to make him and his men comfortable.

At this time, Marzwe, Gambo’s head Induna, was camped with many of his people round the base of the hill on which my fort stood. As he had often expressed a fear lest the remainder of his people, who were living at their kraals some eight miles to the west, should be attacked some fine morning by Maiyaisa’s impi, I had repeatedly told him to bring all his women and children to the immediate vicinity of the fort, since, as I had only ten serviceable horses at my disposal, it was out of the question to attempt any attack on a large impi in a thickly-wooded country, although I should be able to protect any of his tribe who were willing to take quarters round the walls of my fort.

On my last return from Bulawayo, I found that Marzwe had taken my advice, and had sent messengers on the Saturday morning to call all his people in to the fort. These men ought to have returned with the women and children on the following day, but owing to their dilatory ways, and their unfailing habit of “never doing to-day what can be put off till to-morrow,” they did not do so.

On the following morning, Monday, 4th May, Lieutenants Parkin and Webb started off early for the Khami river, taking the mule waggon with them, Lieutenant Howard and myself intending to follow them up and choose a site for the fort immediately after breakfast. Just before discussing this meal, Marzwe came out and reported to me that one of his men had heard shots fired in the direction of his kraal. None of my sentries or horse-guards having heard these shots, I half thought there was no truth in the report. However, I sent Mr. Simms and two other good men to scout round the back of some kopjes, about two miles to the west of our position, beyond which the shots were said to have been fired.

Shortly after the scouts had left, two of the men sent on the previous Saturday to bring in the women and children turned up, saying that Marzwe’s town had been attacked at daylight by a portion of Maiyaisa’s impi, and some of his people killed. A little later a young girl arrived at the fort with an assegai-wound in her right side just above the hip-bone. The wound was not a dangerous one, and after it had been washed and dressed, the child was able to tell her story, which was to the effect that Marzwe’s kraal had been surrounded in the night, and every man, woman, and child in it murdered just at dawn.

Although, with the few mounted men at my disposal, I knew it would be madness to engage any large number of Matabele, unless I could get them in perfectly open country where there was no chance of being surrounded, I was not inclined to let this affair pass without endeavouring to ascertain exactly what had happened. Van Rooyen at once agreed to put off his visit to Bulawayo and accompany me with his three troopers to the scene of the reported massacre, and I sent a messenger to tell Lieutenant Parkin to return immediately to Mabukitwani with ten good men mounted on his best horses. When he arrived, my three scouts had also returned, having seen nothing, and I found myself in command of about twenty-five mounted men; some of the horses, however, were in wretched condition, and altogether unfit for hard work.

When the report of the massacre of his whole family, as well as a large number of his people, was brought to Marzwe, he received it with the utmost stoicism, only saying, “They wanted me; they were looking for me; they wanted my skin.” Whether he believed it or not I cannot say, but he never betrayed the slightest sign of emotion.

It was already past mid-day when I was at last able to get away with my little force, travelling across country under the guidance of an elderly savage armed with a shield, and two long-bladed insinuating-looking assegais, and at the same time adorned with a chimney-pot hat, of all things in the world, thus combining in his own person the attributes of primitive savagery and the most advanced civilisation of Western Europe.

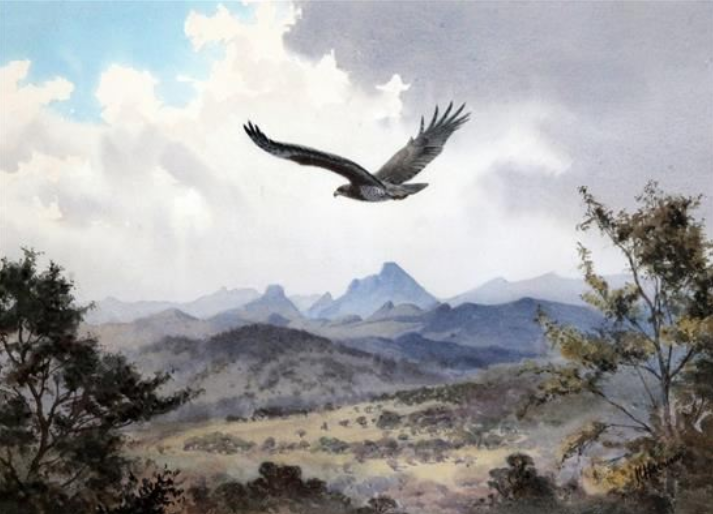

Before we were a couple of miles from camp we met a lot of women and children making for the fort, who said that they had fled from some of Marzwe’s outlying villages early that morning as they had heard firing going on in the direction of the chief’s kraal. Soon after passing these people we got into country where a small force such as mine might have been very easily surrounded and cut up by a hostile impi, as the ground was very broken and on every side of us were small hills and rocky ridges, the whole being covered with dense, scrubby bush, in many parts of which a Kafir would have been invisible at a distance of thirty yards. Had this sort of country continued for any great distance, I would not have risked taking my men on indefinitely over ground so very favourable to any force of hostile Matabele which might chance to be there. However, after a time we emerged into country of a more open character, where the bush was much less dense, and where one was not constantly shut in amongst kopjes and scrub-covered ridges.

Just here one of my flanking parties came on a woman carrying a large bundle of blankets and other household goods on her head. On being questioned, she told us that at daylight that morning Marzwe’s kraal had been attacked and three of his men killed, as well as one girl who had endeavoured to escape with the rest of the men. The girl referred to proved afterwards to be the damsel who had been wounded in the side by an assegai, but who had managed to evade her enemies and make her way to our fort at Mabukitwani. All the rest of the women and children, together with the cattle, sheep, and goats, the woman said, had been captured by Maiyaisa’s people, who, however, she thought were in no great force, being only a small raiding party detached from the main body at the Khami river.

But now comes the sequel, about which the wounded girl had known nothing. Amongst Marzwe’s men who had escaped from the first onslaught on the kraal was one Obas. This man had recognised that the attacking force was not a large one, and he at once went round to all the outlying villages and collected a very considerable number of his chief’s retainers, and taking command of them, followed up the raiders, and not only rescued all the women and children who had been taken captive but also killed eleven of the enemy, and retook all the cattle, sheep, and goats they were driving off. This good news was soon confirmed by Obas himself, whom we met coming on with all the recaptured women and children and cattle. He was a well-built, active-looking Kafir of middle height, light in colour, and with good features, altogether a good specimen of the best type of Matabele. He was armed with a Martini-Henry rifle, as were some few of his followers, whilst all carried assegais. He told us much the same story as we had heard from the woman who had just passed, except that he informed us that the number of Marzwe’s men who had been killed was four, instead of three.

There was now no necessity to proceed any further, so we turned back to the fort, where all Marzwe’s people arrived safely the same evening.

Early the following morning I rode over to the Khami with Lieutenant Howard, and after selecting a site for the fort which was to be built there, and leaving Lieutenant Howard in charge, returned to Mabukitwani. Here I found a telegram from Colonel Napier, which had been sent on to me by Captain Molyneux from Fig Tree. It was to the effect that I was to at once collect a force of forty mounted and eighty dismounted men from all the forts along the road, including Mangwe, and march them in to Bulawayo by Friday evening, as they were required to form part of a column which was to leave for the Tchangani on the following day, Saturday, 9th May.

As the time was so short, I rode the same evening (Tuesday) to Fig Tree in order to despatch a telegram as soon as possible to Major Armstrong, asking him to send me up twenty mounted men from the garrisons of Matoli and Mangwe, and on Wednesday I made all arrangements at the other forts. As Colonel Napier particularly wished Captain Molyneux and Lieutenant Howard to accompany the column, I put Lieutenant Stewart in command at Fig Tree, whilst Lieutenant Parkin took charge of the fort at the Khami river, Lieutenant Grenfell taking over the command of my own fort.

On Thursday evening I had all the men from the lower forts mustered at Mabukitwani, and after a cold rainy night we marched to Bulawayo, picking up the other detachments on our way, and reaching town before sundown on Friday evening, 8th May.