Editor’s Note: The following comprises the seventeenth chapter of Sunshine and Storm in Rhodesia, by Frederick Courteney Selous (published 1896). All spelling in the original.

CHAPTER XVII

On the day before the return of Brand’s patrol, the first news was received from Belingwe that had reached Bulawayo since the outbreak of the insurrection. The despatch was from Captain Laing, who was in command there, and was to the effect that all the whites in the district were in laager, and that they felt confident of being able to resist any attack made upon them by the natives.

This news gave great relief to many people who had friends in the Belingwe district, for it was not known whether they had been able to collect together and form a laager, or whether they had been surprised and murdered before they were aware that anything was amiss; as indeed they would have been, in all probability, had not Mr. H. P. Fynn, the native commissioner in the Insiza district, sent a message to Captain Laing to warn him that a native rising seemed imminent immediately after he was informed of the murder of Mr. Maddocks. This message was faithfully carried by one of Mr. Fynn’s native policemen, and Captain Laing, recognising the gravity of the situation, at once acted with the promptitude and decision which always distinguish him, and ordered all the whites in his district to immediately come in to laager at Belingwe.

They were only just in time, for the natives showed their teeth very soon afterwards, and although fearing to attack the laager, succeeded in driving off a considerable number of cattle. Captain Laing, accompanied by only nine men—all he was able to mount—then in his turn attacked the insurgents, and succeeded in recapturing some of the cattle, though these were of little value, as the rinderpest was amongst them. It is worthy of remark that the native policeman who took the message to Captain Laing, which probably saved many white men’s lives in the Belingwe district, never returned to his duty, but as is now known, went over to the rebels with his rifle and bandoleer full of cartridges. This fact, taken in conjunction with many other circumstances, goes to prove that the secret of the actual date of the outbreak of the insurrection was not known to the mass of the people, though probably, owing to the prophetic utterances ascribed to the Umlimo, which had been diligently circulated amongst them, they were in a state of expectancy; but this policeman, for instance, must have been thoroughly taken by surprise, and after the first murders remained loyal to the Government until he was got at by some one capable of explaining to him the scope of the whole plot.

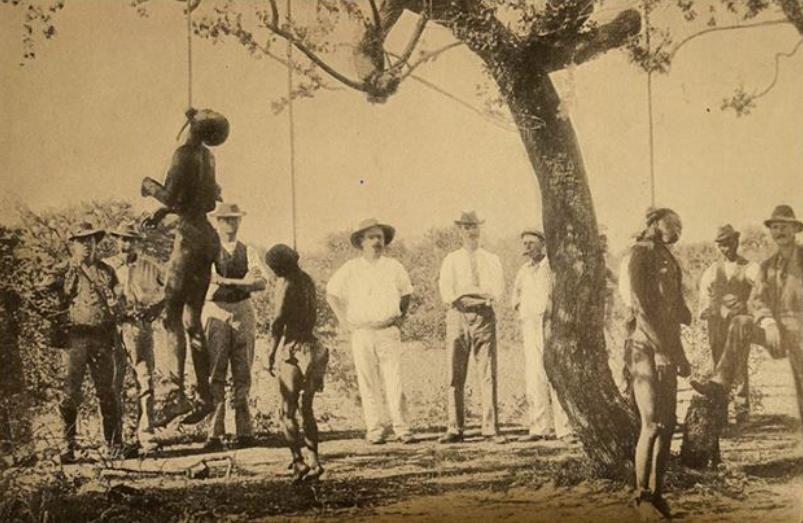

On 10th April, too, a further excitement was caused in Bulawayo by the arrest of three Matabele rebels. They were captured near Soluso’s, some twenty miles west of Bulawayo, by Marzwe’s Friendlies, and sent in to town by Josana, having been caught red-handed, looting and burning property belonging to white men. I was present when the evidence was taken, and it certainly seemed to me to be overwhelming, especially as one of them was known to Mr. Colenbrander, and they all three acknowledged themselves to be the subjects of a certain Induna named Maiyaisa, who with all his people has been amongst the rebels from the first outbreak of the insurrection. They were caught, too, with assegais in their hands, looting a white man’s farm, so that it might very reasonably be asked “que diable allaient-ils faire dans cette galère?”

At any rate they were condemned to death, and hanged forthwith, all three on one tree on the outskirts of Bulawayo. Besides these three men who had been incontestably guilty of taking part in the rebellion, and who were hanged together, six others were hanged singly and at different times, all of whom, if they were tried in a somewhat rough-and-ready fashion, were undoubtedly spies and rebels.

These are the only Matabele who have been hanged during the present insurrection, and a letter therefore on the subject of hanging natives which appeared in the Daily Graphic of Saturday, 13th June, purporting to have been written by a young tradesman of Bulawayo, is a trifle incorrect, to say the least of it. A portion of the letter runs as follows: “My stand has one big tree on it, and it is often used as a gallows. Yesterday there was a goodly crop of seven Matabele hanging there; to-day there are eight, the eighth being a nigger who was heard boasting to a companion that he had helped to kill white men, and got back to town without being suspected.”

This letter was reproduced by Mr. Labouchere in Truth, as well as another he got hold of at the same time, in which the writer expresses it as his opinion that “it is grand fun potting niggers off, and seeing them fall like nine-pins,” while further on he speaks of it being “quite a nice sight” to see men shot as spies. I can quite believe that a man who can write in this strain would take pleasure in, or “would not object,” as he puts it, to seeing Kafirs shot, but I doubt very much if such an one would ever risk his skin to enjoy “the grand fun” he speaks of.

It seems a pity that a writer who takes “Truth” as the motto of his paper, should seize upon every little scrap of published matter he can discover (apparently without inquiry as to its real value), and not only reproduce it as gospel in an ensuing number of his journal, but found a sermon upon it into the bargain on the iniquities of his fellow-countrymen in Rhodesia. However, we have the consolation of knowing that nothing has discredited the editor of Truth in the eyes of all fair-minded men so much as the hostile feeling he has ever shown against the British settlers in Rhodesia, whilst, happily for that colony, his rage is as impotent as that of “a viper gnawing at an old file.”

During the week in which the aforesaid Kafirs were hanged, some parties of Matabele approached the town very closely at nights, and on the night of 6th April one of them succeeded in capturing a herd of cattle within a mile and a half of the hospital, at the same time murdering some Zambesi Kafirs who were sleeping outside the cattle kraal. As at this time there was a herd of cattle which was penned every night in a kraal near Dr. Sauer’s house, some two miles away on the other side of the town, I was asked to take some of my men and lie in wait for any Matabele who might attempt to capture them on the following night.

I went down and reconnoitred the position during the day, and after dark rode down with fifteen good men. We first off-saddled our horses, and tied them up within the paling round Dr. Sauer’s house, and then took up our positions along two walls of the square stone cattle kraal. During the night, the weather, which had been fine and warm, suddenly changed; a cold wind sprang up, and masses of cloud spread over the sky from the south-east. It looked as if it was going to rain every minute, but luckily the wind kept it off. However, it was bitterly cold, and we were all of us very glad when day at last dawned and our weary vigil was over, for no Kafirs came near us; and when I examined the cattle I did not think it likely they would, as the rinderpest was rife amongst them, two lying dead in the kraal, whilst many others, the herd boy told us, lay rotting about the veld all round.

About this time the authorities determined to carry out a scheme for keeping open communications with the south by means of forts which were to be built along the road between Bulawayo and Mangwe. As a commencement in this direction, Captain Molyneux left Bulawayo, on Saturday, 11th April, with sixty men to establish a fort at Fig Tree, distant thirty miles down the road, whilst at the same time Captain Luck was ordered up from Mangwe with fifty men to build a second fort some fifteen miles from that place, in the centre of the hilly country through which the coach road passes.

Two days later I was sent down the road to establish further forts between Fig Tree and Mangwe, and to take command of all garrisons on the road, the force with which I left town consisting of sixty men of H troop of the Bulawayo Field Force (my own), forty men of E troop under Captain Halsted, and twenty of the Africander Corps under Lieutenant Webb.

We left Bulawayo on the evening of Monday, 13th April, and slept that night at Wilson’s farm, reaching Mabukitwani the following evening. From information I received there concerning the movements of the Matabele, I became convinced that the dangerous part of the road was that portion of it lying between Bulawayo and Fig Tree, and not the hill passes farther on, as the inhabitants of the latter are all Makalakas, the rebel Matabele who had been living amongst them having all come up nearer to Bulawayo, and joined their compatriots on the Khami river.

According to the plan which I had been asked to carry out, the thirty miles of road between Bulawayo and Fig Tree would have been left entirely undefended, which did not appear to me to be at all advisable in view of the fact that there was a large impi under the Induna Maiyaisa encamped on the Khami, only twelve miles below the ford on the main coach road. I therefore took it upon myself to send Lieutenant Webb with his twenty men back to the Khami river, to commence a fort there, at the same time despatching a messenger to Bulawayo requesting Colonel Napier to reinforce him with another twenty or thirty men. At the same time I gave it as my opinion that a fort ought also to be established at Mabukitwani.

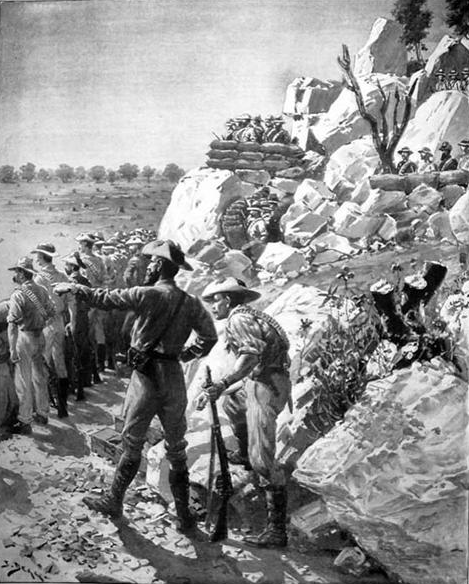

On Wednesday afternoon we reached Fig Tree, where we found that Captain Molyneux had already nearly completed an almost impregnable fort, which had been built on a small isolated kopje, itself a natural stronghold, about 200 yards from the mule stables, hotel, and telegraph office at Fig Tree. The natural strength of this kopje had been most cunningly taken advantage of and increased by blasting a rock out here and there, and fortifying the weak places with sand-bags. Good water was obtainable in the bed of a stream at the very foot of the kopje, whilst a recess amongst the rocks near its base had been cleared in such a way as to form a stable within which some twenty horses could be completely sheltered from the bullets of any attacking force. Altogether, Fort Molyneux was a perfect little place of its kind, and did every credit to the very capable officer by whom it was built.

On the following day we went on to Shashani neck, some five and a half miles beyond Fort Molyneux. Here the road descends for a distance of three miles into the Shashani valley, winding continually in and out amongst thickly-wooded granite hills. Had the Kafirs, at the commencement of the insurrection, put a force of 1000 men armed with rifles, backed by another 1000 with assegais, into this pass, it is my opinion that they would have completely cut off all communication between Bulawayo and the south until a body of troops at least 1000 strong had been sent up from Mafeking to open the road. However, luckily they missed this opportunity, as they have missed every other chance they have had of striking a really effective blow at the white men. In fact, they have shown a general want of intelligence that stamps them as an altogether inferior people, in brain capacity at least, to the European.

About one-third of the way down the pass Captain Halsted and I found a kopje close to water, which commanded the road, and at the same time could be rendered absolutely impregnable to such enemies as the Matabele with a comparatively small amount of labour. Here I left Captain Halsted with the men of E troop to build a fort, and on Friday morning, 17th April, went on with my own troop to the Matoli river where Captain Luck had already almost completed a strong fort of earthworks and palisades in the centre of a large open space amongst the hills, by none of which, however, was it commanded. Here I met Major Armstrong from Mangwe, and as all I heard from him regarding the state of affairs in his district only confirmed me in the opinion that it would be a waste of time and men to build another fort between Matoli and Mangwe, as I had been instructed to do, whilst on the other hand I felt that it was of vital importance to establish forts without delay between Fig Tree and Bulawayo, I determined to return to town and lay my views before the administrator personally before proceeding farther southwards.

Major Armstrong having also official business to transact in Bulawayo, we arranged to ride in together forthwith. On passing Captain Halsted late in the afternoon we found that he had already made wonderful progress with the stronghold which is now known to fame as Fort Halsted. Just at dusk we reached Fort Molyneux, where we got an excellent dinner and were made comfortable for the night. Here I received a telegram from Colonel Napier, telling me that at the present moment he could not possibly spare any men from Bulawayo to reinforce Lieutenant Webb at the Khami river, as the Kafirs were massing round the town; and that as twenty men was too small a number to leave alone without reinforcements, he had ordered him to fall back on Fig Tree, or join Captain Halsted for the present.

At daylight Lieutenant Webb turned up, and as Captain Molyneux had over fifty men at Fig Tree, and Captain Halsted only forty, I sent him on to the latter. Major Armstrong and I then saddled up, and reached Bulawayo about two o’clock on Saturday, 18th April, having passed the down coach accompanied by a strong escort at the Khami river. The situation in Matabeleland was now a sufficiently curious one. In Bulawayo were some 1500 white men, women, and children, all of whom, although they were able to visit their houses in different parts of the town by day, had to seek safety within the laager at nights, and were not allowed to leave it before seven o’clock in the morning. At this time the whole of Matabeleland, with the exception of Bulawayo, and the laagers of Gwelo and Belingwe, was absolutely in the hands of the Kafirs, although, apparently by the orders of the Umlimo, the main road to the south had not been closed. A large impi lay at Mr. Crewe’s farm, Redbank, on the Khami river, about twelve miles to the west of the town, besides which some thousands of rebels, amongst whom it was said was Lo Bengula’s eldest son, Inyamanda, were camped all along the Umguza, considerable numbers of them being actually within three miles of Bulawayo, whilst other two large impis had taken up their quarters amongst the Elibaini Hills, and in the neighbourhood of Intaba Induna, there being altogether not less than 10,000 hostile natives spread out in a semicircle from the west to the north-east of the town. Had these different impis only combined and acted in concert under one leader they might have accomplished something; but each impi appears to have been acting independently of the others, and my own belief is that they kept hanging round the town without any general plan of action, in the expectation of some supernatural interference by the deity on their behalf. At least this is what we hear from themselves, and I think it is the truth. Besides the impis to the north and west, there were others encamped within the edge of the Matopo Hills. These latter, however, although they blocked the Tuli road and destroyed the mission station at Hope Fountain, which had been established for over twenty-five years, never approached Bulawayo.