Editor’s Note: The following comprises the fourteenth chapter of Sunshine and Storm in Rhodesia, by Frederick Courteney Selous (published 1896). All spelling in the original.

CHAPTER XIV

Besides the patrols of which I have already spoken that were sent out from Bulawayo during the first days of the insurrection, I must not forget that which was taken down to the Gwanda district by Mr. James Dawson. Mr. Dawson, who has lived amongst the natives of Matabeleland for many years, and both speaks their language and understands their character well, could not believe that a general rising throughout the country was possible, and even after hearing of the murders in the Insiza and Filibusi districts, and my own report as to what had taken place on Essexvale, imagined that the disturbance was only local. However, in order to assure himself of the true position of affairs, he got together some ten or twelve men, and leaving Bulawayo with them on Wednesday night, 25th March, proceeded down the Tuli road to his own store at “Amanzi minyama,” situated in the Gwanda district, and distant about seventy-five miles from Bulawayo.

On his way there he found everything perfectly quiet along the road, all the wayside stores being still in the occupation of their owners, none of whom had heard anything about the native rising—a state of things which of course confirmed Mr. Dawson in his scepticism.

On the return journey, however, shortly before reaching Spiro’s store, which is distant thirty-seven miles from Bulawayo, the fresh tracks of numbers of natives—men, women, and children—as well as of cattle, goats, and sheep, were noticed crossing the road. These were doubtless the trails made by the Matabele from the Filibusi district, who were making their way to the Matopo Hills, and at once aroused suspicion.

Spiro’s store was reached on Sunday, a few hours after I had left it the same morning on my way into the hills. Here Mr. Dawson found no one, for after my departure the boys who had been looking after the coach mules became frightened and took them in to Bulawayo, leaving the cattle behind; and these were still in the kraal, with no one to tend them, when Mr. Dawson passed. Not quite liking the look of things, the patrol went on beyond the store, and slept some four miles away from it.

On the following morning early they reached the wayside hotel at the Umzingwani river, which we had left at sundown on the evening before. Here in one of the huts were found the blood-stained shirt of Mr. Munzberg, and also a sock soaked with blood that had been taken from Mr. Stracey. During Monday Mr. Dawson and his men remained at the Umzingwani, but sent messengers to Bulawayo to obtain news as to what was going on.

Late that evening an answer was received requesting him to come on to town at once, as the Kafirs were reported to be massing in the neighbourhood. Before this there had been several alarms, and it was believed that natives were on the watch round about the store. Thus when the start was made for Bulawayo, the lights were left burning, in order to make the Kafirs believe that some of the party were still in the house. Arrived at the river some 600 yards distant from the store, Mr. Dawson rode back alone to reconnoitre, but hearing natives talking, retired and rejoined his men.

Early on Tuesday morning Inspector Southey was met with a small force at the head of the pass leading down to the Umzingwani. He had been sent out to escort the coach to Bulawayo, which was now some time overdue from Tuli. However, as Mr. Dawson had heard nothing of this coach, it was thought that it must have turned back; so Inspector Southey, who had been ordered not to descend the pass, returned to town, where shortly after his arrival the coach turned up too without an escort.

This was the last coach that ran on the Tuli road, and it seems to have been missed by the natives by a miracle, as they had broken into the Umzingwani store and gone away again in the interval between the time of its arrival there and Mr. Dawson’s departure.

This coach reached Bulawayo on the morning of Tuesday, 31st March, and on the same day—the day after my own return from the Matopos—I was asked to take a patrol of twenty-five men down the Mangwe road, in order to ascertain if it was still clear, as a coach loaded with rifles and ammunition and ten waggon-loads of provisions were on their way up.

We left town about 2 P.M., each man carrying three days’ rations with him, and reaching Mabukitwani, twenty miles distant from Bulawayo, the same night, arrived at “Fig Tree” by noon the following day, where we found a store and mule stable in charge of Mr. Elliott.

The people living in the neighbourhood are nearly all of Makalaka descent, and have taken no part in the present insurrection. At the time of my visit they were in a great state of alarm, and the greater part of them had left their villages and fled into the hills, fearing lest the white men should visit the sins of the insurgents upon them. I therefore sent one of Mr. Elliott’s boys to call the principal Induna to come and see me. With this man, an intelligent-looking Makalaka named Jackal, who bears a striking resemblance to the chief Khama, I had a long interview, and finally persuaded him to send messengers to the refugees ordering them to return to their kraals. Jackal assured me that the first news of the rebellion was brought to him by the son of Umfaizella (the brother of Lo Bengula, who with Umlugulu and others is responsible for the murders at Edkins’ store), who was sent by his father to incite some of the Makalaka to revolt. When he found that Jackal’s people did not seem very anxious to assist the Matabele in their attempt to regain their independence, he said to him, “You say that your people don’t want to fight; that they wish to sit still. Don’t you know that the white men are killing all the black men they can catch? Don’t you know that they have shot Gambo through the head, and thrown his body to the birds? Have you not heard that every Kafir boy who was working in Bulawayo has had his throat cut?” “I did not believe him,” said Jackal, “and soon afterwards one of my own men, who had been working in town, came home, and told me that the white men had killed no one in Bulawayo except a few Matabele spies. Then I knew that the son of Umfaizella had lied to me, but still the bad news frightened my people.” I may here state that Jackal expressed the opinion that if they were unable to kill all the white men, a large section of the Matabele would probably leave the country with as many cattle as they could get together, and seek a new home beyond the Zambesi. What amount of truth there may be in this view, and how far the original plan may have been modified owing to the destruction of all the cattle by the rinderpest, remains to be seen. At present, however, no section of the tribe seems actually to have made a move beyond the outskirts of Matabeleland proper.

In the afternoon we proceeded to the Shashani. Before reaching “Fig Tree,” the coach, loaded with ammunition, had passed us on its way to Bulawayo in charge of the escort that had accompanied it from Mangwe. As, according to the information I had received before leaving town, the convoy of waggons ought now to have been close at hand, and I did not wish to tire all my horses by taking them any farther than necessary down the road, I left Lieutenant Grenfell in charge of the patrol at the deserted shanty, which had done duty as an hotel, near to which we had off-saddled, and rode on alone.

Shortly before reaching the Shashani hotel we had met a light waggonette drawn by a team of horses on its way to Bulawayo. In it were two gentlemen, Captain Lumsden (late of the 4th Battalion Scottish Rifles) and Mr. Frost, on their way to Matabeleland on a shooting expedition. We halted and gave one another the news from up and down country respectively, and had a laugh and a joke about the kind of shooting one was likely to get in Matabeleland at the present time. When Captain Lumsden got out of the waggonette I saw what a fine specimen of a man he was—tall and broad-shouldered, with a pleasant face and keen blue eye—and I little thought that when next I met him, only a week later, it would be in the Bulawayo hospital, where, poor fellow, he lay with a leg shattered by a Kafir’s bullet, on what soon proved to be his deathbed, for he died from the effects of the subsequent amputation of the limb.

After leaving my men I rode quietly on, but only met the waggons I was looking out for when close to Mangwe. Having many friends in the laager there, I determined to ride a little farther and pay them a visit. First, however, I exhorted the man in charge of the waggons to push on at once, as I was anxious to return to Bulawayo as soon as possible, in the hope of getting something more exciting to do there than escorting waggons.

When still some three miles from Mangwe I met a party of horsemen riding towards me along the road. They proved to be old friends who had come out to meet me, as they had heard by telegraph that I was coming their way. Amongst them was one of my oldest and most esteemed friends, Cornelius Van Rooyen, with whom in the good old days I had wandered and hunted for months together over the then unknown wilds of Mashunaland.

Arrived at the laager, I received a very warm welcome from both Dutch and English. Major Armstrong was in command, whom, though a very young man, I thought both shrewd and capable, and the excellent service he has done for the Government during the present insurrection has, I think, been fully recognised.

Before leaving Bulawayo I had heard it said that in the Mangwe laager order and discipline were conspicuous by their absence; but this I did not find to be at all the case. On the contrary, it seemed to me that Major Armstrong and Commandant Van Rooyen, by the exercise of great tact, had between them got everything into excellent order; and this is no small praise, for it must be remembered that the occupants of the Mangwe laager belonged to two nationalities, Dutch and English, each of which has its own way of doing things, and the two can only be brought to work harmoniously together by the exercise of both forbearance and good sense on the part of the officer commanding the combined force.

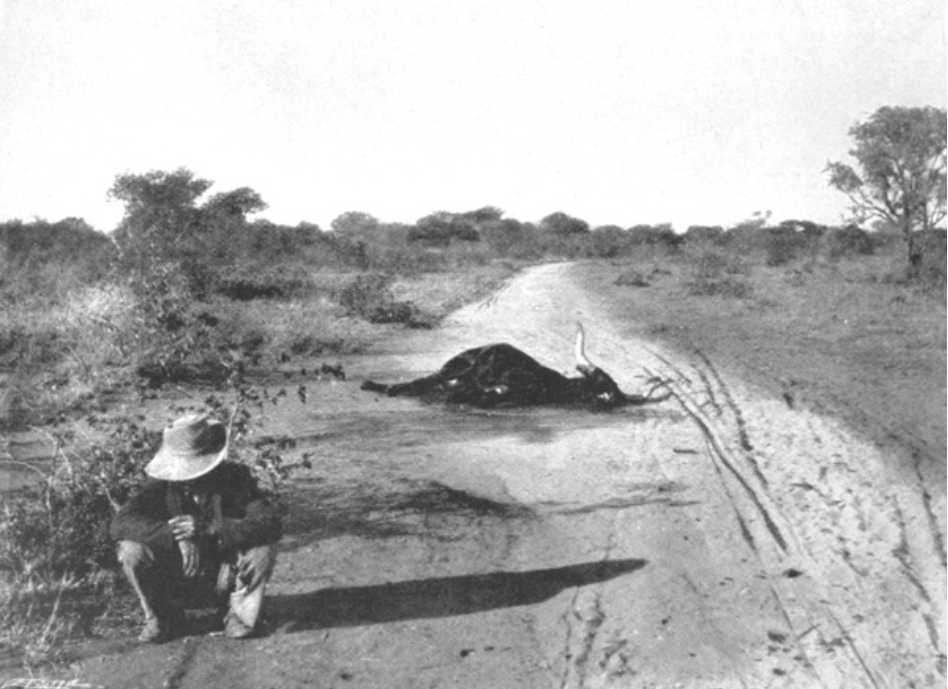

All my Dutch friends at Mangwe had suffered terrible losses amongst their stock from the rinderpest; indeed, some who had been rich men a couple of months before, possessing several hundred head of stock, had now scarcely a beast left. All along the road, too, from Bulawayo to Mangwe the evidences of the ruthless severity of this plague were most lamentable. Hundreds of carcasses in every stage of putrefaction everywhere lined the track, whilst here and there were groups of empty waggons abandoned by their owners, who, having lost their means of livelihood through the death of their oxen, had left the rest of their property standing uncared for in the wilderness, and walked away ruined men.

At Wilson’s farm, six miles from Bulawayo, where herds of infected cattle had been slaughtered in the hopeless endeavour to stamp out the disease, acres of carcasses were lying festering in the sun, and any one passing along the road did not require to look at them to know they were there. Strangely enough, in spite of the exceptional opportunities offering for free meals throughout Matabeleland at this time, not a vulture was to be seen. I have heard it said that too hearty an indulgence in rinderpest meat in the early days of the plague killed all the vultures, and whether this is so or not, certain it is that these useful birds are now as scarce as cows in Matabeleland.