Editor’s Note: The following comprises the twelfth chapter of Sunshine and Storm in Rhodesia, by Frederick Courteney Selous (published 1896). All spelling in the original.

CHAPTER XII

On our return to Bulawayo, we found that a very strong laager had been formed in the large square round the Market Buildings. Within this laager the whole population of the town, with few exceptions, slept every night; the women and children within the buildings, whilst the men manned the waggons in readiness to resist any sudden attack.

The Bulawayo laager was probably the strongest ever constructed in South Africa, and the whole Matabele nation, I think, would never have taken it by assault. But if 2000 of them, or even a smaller number, had made a night attack upon the town before the laager had been formed, I think it more than probable that the entire white population would have been massacred. It appears that there was a terrible scare on the very night on which I had left the town for Essexvale, viz. Wednesday, 25th March. This scare was absolutely groundless and seems to have been caused by a drunken man galloping about calling out “The Matabele are here; the Matabele are here.”

My wife was resting in Mrs. Spreckley’s house at the time, being much fatigued by her long ride in the hot sun from Essexvale. However, she and her kind hostess, as well as all the other ladies living on the suburban stands, were hurried over to the new Club-house, nearly a mile distant, in the centre of the town. Here the large number of women and children in Bulawayo, many of them hastily summoned from their beds, and most of them terribly frightened, passed a miserable night all huddled up together, but getting neither rest nor sleep, as they were constantly kept on the qui vive by fresh rumours, all equally groundless, as happily at this time there was no force of hostile natives within twenty miles of Bulawayo. On the following day the laager was formed, and by the time I got back to town Colonel Spreckley and Mr. Scott (the town major) had, after an immense amount of hard work, got everything into good order.

These two gentlemen deserve the utmost credit not only for getting the laager into good order, but also for keeping it in that condition for the next two months. Major Scott was indefatigable in looking after the sanitary arrangements, whilst Colonel Spreckley, by his genial good nature, backed by great common sense and strength of character, kept all the various human elements shut up in that confined space not only in good order but in good humour. Nobody in Bulawayo, I think, could have performed the very difficult duties required from the chief officer in charge of the laager so ably as Colonel Spreckley during the first two months of the insurrection, and his conduct was all the more admirable because he was carrying out a very arduous and harassing duty against his inclination, or rather burning desire, to be out of town at the head of a patrol doing active work against the insurgents.

Soon after my arrival in town, I was delighted to meet the Native Commissioner of my district, Mr. Jackson, whom I had never thought to see again. He and his white companions had received warning of the rising from his sub-inspector, and were also cautioned lest there should be a plot on foot for their murder by the native police. At this time, however, the ninety men they had with them, each of whom was armed with a Winchester rifle and seventy rounds of ammunition, did not know that the rebellion had commenced, and they managed to bring them all in to Bulawayo without any trouble, where they were at once disarmed.

Now by this time it had become evident that the insurrection had become general throughout the length and breadth of Matabeleland, and I will give a brief account of what had happened so far as is known.

I have already related that Mr. Cumming and another man brought the first news of the murders of white men in the Insiza district to Bulawayo. On reaching Lee’s store, twenty-four miles from the town, they found that their horses were completely knocked up, and they could thus only have proceeded on foot, had not Mr. Claude Grenfell just happened to be passing the store with a cart and horses on his way from Gwelo to Bulawayo.

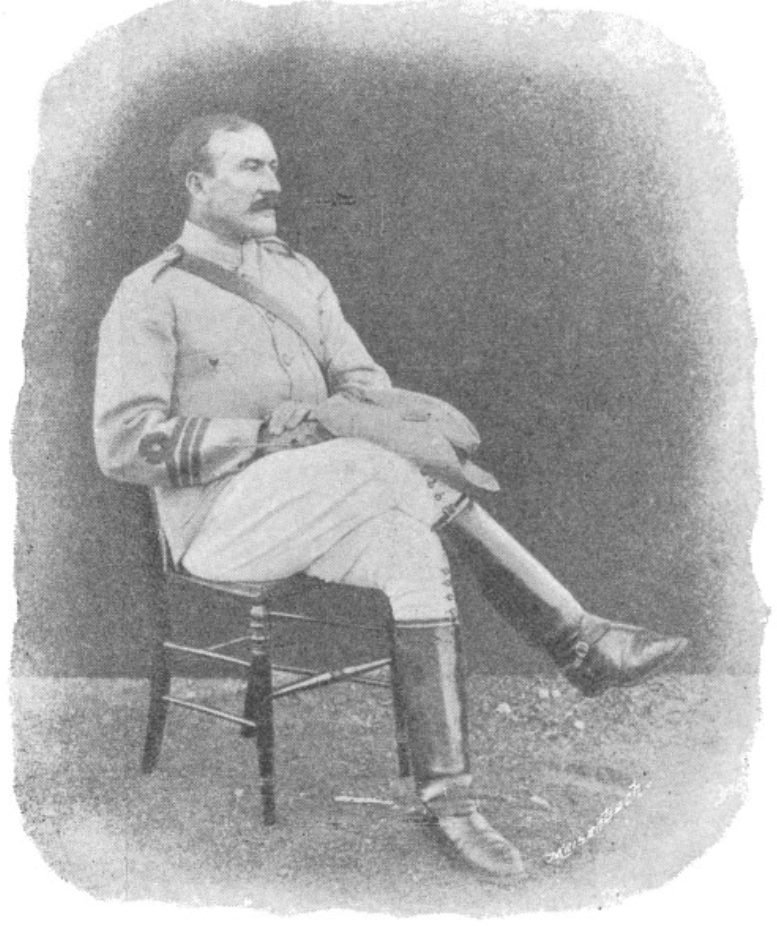

On hearing the alarming news Mr. Grenfell took Mr. Cumming on with him at once to headquarters, his companion, Mr. Edmunds, giving up his seat to him, and walking. Before reaching Lee’s store, Mr. Grenfell had met Mr. George Grey, travelling alone in a Cape cart with a coloured boy, on his way to inspect some of his mining properties near the Tchangani river, and when the news of the murders in the Insiza district became known, much anxiety was naturally felt concerning Mr. Grey’s safety, as well as that of all other Europeans who were living at a distance from Bulawayo in mining camps or on lonely farms.

Early on Thursday morning, however, Mr. Grey returned to town, having escaped death by the merest chance, as he must only just have escaped falling into the hands of more than one party of murderers.

On reaching the Pongo store some twelve miles from the Tchangani river, Mr. Grey had found all the outhouses just burnt. The store itself seemed to have been looted, but was not at this time burnt down. No trace of the owners could be found, but the ground was thickly covered with the naked footprints of natives, and, more ominous still, a large pool of blood was seen in the road in front of the store. We now know that at this time the recently-murdered corpses of three white men were lying, two of them close to the store, and the third on the top of a rise a short distance away. I was present some six weeks later when the bodies were discovered and buried. The unfortunate men must have been suddenly attacked with knob-kerries and axes, as their skulls had all been smashed in. In this instance the clothes were not removed from the bodies.

This was the first intimation that Mr. Grey got that mischief was brewing in the country. Soon after passing the Pongo store, he turned off the main road and went down to the Eagle mine some four miles distant. This he found had been only recently deserted by the Europeans employed there, and with his suspicions now fully aroused he returned at once to the main road, and made for the Tchangani store. On his way there he came across a white man on the roadside, who had escaped from a party of Kafirs, after receiving two severe battle-axe wounds, one of which had cut his face open from nose to ear, whilst the second had cut his arm to the bone and severed all the tendons of the wrist. This man had been working with two companions on a farm in the neighbourhood, when on the previous day—Tuesday, 24th March—they had been suddenly and without any warning attacked by a party of Kafirs armed with knob-kerries and battle-axes. Although two of them were wounded, they managed to retreat to their hut, on which the natives, probably thinking that they had firearms there, retired.

After sundown the three white men left their hut, intending to make for Stewart’s store at the Tekwe. Unfortunately it was a bright moonlight night, and the Kafirs must have been watching them, as they immediately followed, and chased them into a maize field, through which they hunted them. During this pursuit the white men became separated. One of them reached Mr. Stewart’s store in safety; the second, Mr. Scott by name, found his way to the road near the Pongo store and was picked up and taken to the Tchangani by Mr. Grey; but the third must have fallen into the hands of the Kafirs, and, of course, been murdered, as he has never again been heard of from that day to this. The man who made his way to the Tekwe had received a severe blow on the head with a knob-kerry.

Arrived at the Tchangani, Mr. Grey found seventeen Europeans in laager there, amongst them the men from the Eagle mine, who had been pursued on their way to the store. The natives, however, were afraid to come to close quarters with them as they were armed with rifles, and at this time the rebels in this district had not yet dug up the firearms which they had buried after the war of 1893, and were therefore only able to kill white men whom they could take by surprise with knob-kerries and axes.

Now fully realising the very serious aspect of affairs, Mr. Grey, instead of remaining in the shelter of the laager, most pluckily determined to return to Bulawayo at once, making use of the post mules along the road, in order to warn all people with as little delay as possible that the Kafirs had risen.

A few hours after he had left the Tchangani, the garrison of the laager was augmented by the arrival of Messrs. Farquhar, Weston Jarvis, Currie, and Mr. Egerton (M.P. for Knutsford) and his son. These gentlemen had been on a hunting trip to the Sebakwe river, and were returning to Bulawayo only just in time, as had they remained out in the veld any longer they would certainly have been murdered, for although they would doubtless have given a very good account of themselves, yet a few men cannot fight an army.

On the following day—Thursday, 26th March—two small patrols were organised and sent out from the Tchangani, one of which, consisting of Mr. Mowbray Farquhar and two companions, visited a mine where a white man was known to have been working a day or two previously, whilst the other, consisting of Mr. Robinson and two others, visited the Pongo store and the Eagle mine. A careful search was made by the latter all round the store, and the bodies of two out of the three men who had been murdered there two days previously were discovered and covered with blankets, which were still in their places when we buried the remains some six weeks later. The third corpse they did not find, as it was lying some distance from the store.

Mr. Farquhar and his two companions visited Comployer’s camp, and found the unfortunate man lying murdered in front of the door of his hut. They tried to get on to Gracey’s camp, but could not do so for fear of being surrounded and cut off by the Kafirs, who were all in their kraals watching them. It has since been ascertained that Gracey was murdered on the same day as Comployer.

On returning to the laager, they found that a mule-waggon had been sent from Gwelo, with orders from the officer commanding there that all Europeans should come in as quickly as possible to assist in the defence of the town against the Kafirs.

Leaving the Tchangani at 5 P.M. on Thursday evening, the whole party reached Gwelo in safety on Friday morning at half-past eight. In the meantime Mr. Grey, travelling at express speed with relays of coach mules, reached Bulawayo early on Thursday morning. On passing the Tekwe store, he found assembled there Mr. Stewart, five other white men, and two women, who were endeavouring to fortify a hut. Promising them speedy relief, Mr. Grey hurried on to warn others of their danger, but beyond the Tekwe he found that the occupants of the roadside hotels and post stations had already taken the alarm and made their way to Bulawayo.

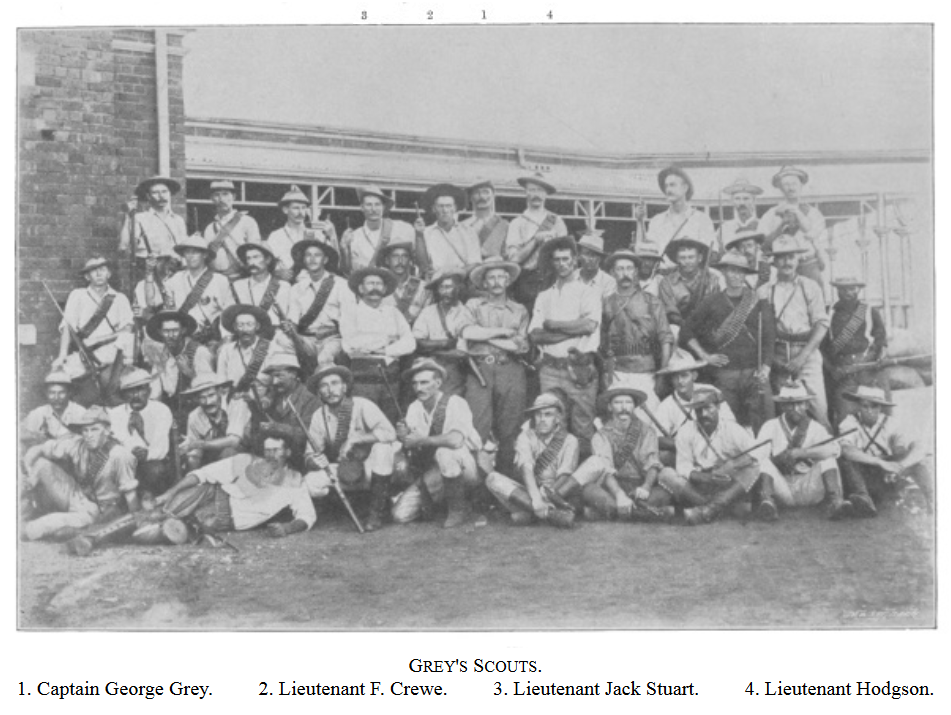

On Thursday, 26th March, Mr. Grey got together twenty-three good men, and started back for the Tekwe that same evening. These men formed the nucleus of a force which has done splendid service in the suppression of the present rebellion, under the name of Grey’s Scouts. They were a picked body of men, and neither their name nor their brave deeds will ever be forgotten in Rhodesia, whilst I think we all regard Captain Grey as one of the finest specimens of an Englishman in the country—quiet, self-contained and unassuming, but at the same time, brave, capable, and energetic.