Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Firemen and Their Exploits, by F. M. Holmes (published 1899). All spelling in the original.

Here are two tarnished and dented helmets of brass. They belonged respectively to Assistant-Officer Ashford and to Fourth-class Fireman Berg, who both lost their lives at the same great conflagration.

About one o’clock in the early morning of December 7th, 1882, the West London policemen, stepping quietly on their beat about Leicester Square, discovered that the Alhambra Theatre was on fire.

A fireman on watch within the building had made the same discovery, and with his comrade was working to subdue the flames. But they proved too strong for the men.

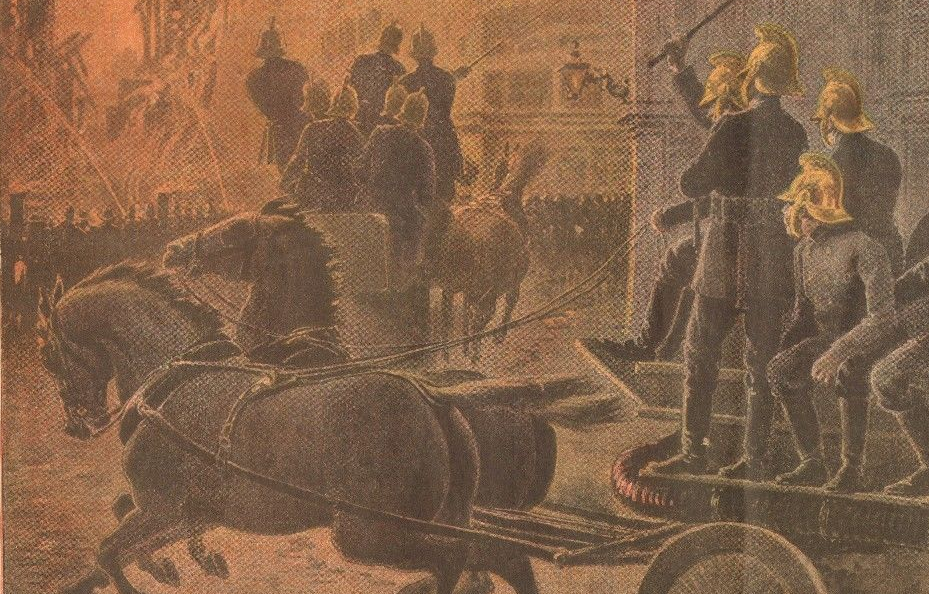

The nearest brigade station was speedily aroused, the news telegraphed to others, and ere long several fire-engines had hurried to the spot. Quickly they were placed at different points about the building, and streams of water were thrown on the fire. But in spite of all efforts, it gained rapidly on the large structure.

The position was fairly high and central, and the flames and ruddy glow in the sky were visible in all parts of London; even at that hour spectators rushed in numbers to the scene and crowded the surrounding streets. It was with difficulty that the police could prevent them from forcing themselves into even dangerous situations.

The heat was intense, and as far off as the other side of the spacious square it struck unpleasantly to the face. The flames darted high in the air as if in triumph, and the huge rolling clouds of smoke became illumined by the brilliant light. Several notable buildings in the neighbourhood stood out clearly in the vivid glow as though in the splendour of a gorgeous sunset, while high amid the towering flames stood the picturesque Oriental minarets of the building as though determined not to yield.

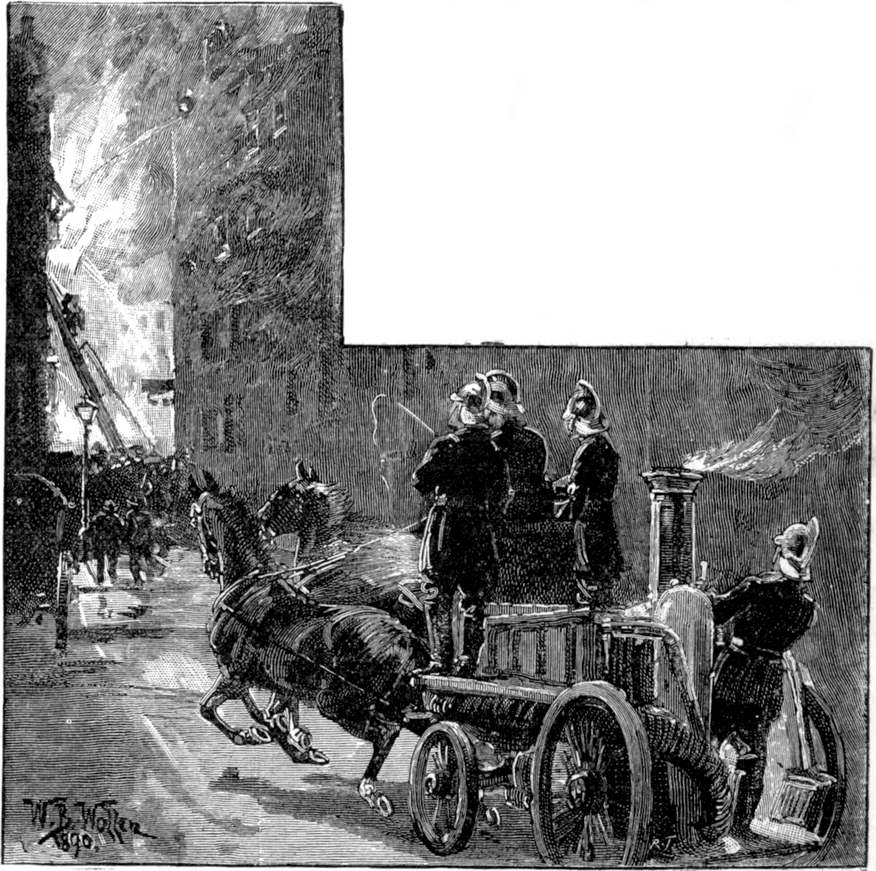

The firemen endured a fearful time. Some stood in the windows, surrounded, it seemed, by sparks of fire. Mounting fire-escapes also, they poured water from these points of vantage into the burning building. By half-past one twenty-four steam fire-engines were at work, and at that time the brigade had only thirty-five effective steamers in the force. At about two o’clock the minarets and the roof fell in with a tremendous crash, and still the flames shot upward from the basement.

Crash now succeeded crash; girders, boxes, galleries, all fell in the general ruin. Moreover, the fire leaped out of the building, and began to attack other houses at the back. A number of small and crowded tenements existed here, and the danger of an extended and disastrous fire became very great. But the efforts of the firemen were happily successful in preventing its increase to any considerable extent.

It was while working on an escape-ladder that Berg met with his death. An escape had been placed against the building next to the front of the theatre, and he was engaged in directing the jet of water from the extended or “fly” ladder fifty feet high, when from some cause—probably the slipperiness of the ladder-rungs—he lost his footing, and crashed head-foremost to the ground.

When taken up, he was found to be insensible; and while the fearful flames were still raging, and his comrades were still at work, he was conveyed to the Charing Cross Hospital. Among other injuries which he had received was a fracture of the head; and after lingering a few days, and lapsing into long fits of unconsciousness, he died.

Not long after Berg was admitted to the hospital on that fearful night, another fireman was carried thither from the same place. This sufferer was Assistant-Officer Ashford, who arrived at the fire in charge of an engine from Southwark. He was standing behind the stage, when a wall fell upon him and crushed him to the ground. His comrades hurried to rescue him, and he was quickly taken to the hospital; but his back was found to be broken, and he had also sustained serious internal injuries. After lingering for a few hours in great pain, he died. He had been thirteen years in the brigade, and was married.

Several other accidents occurred at this great fire. At the same time that Ashford was stricken down, Engineer Chatterton, who was standing near him, was stunned, and narrowly escaped with his life. Four other firemen were also injured, one suffering from burns, one from sprain and contusions of the legs, one from falling through a skylight and cutting his hands, and one from slipping from a steam fire-engine on returning to Rotherhithe and breaking his arm. These incidents show how various are the heavy risks the firemen run in the course of their work.

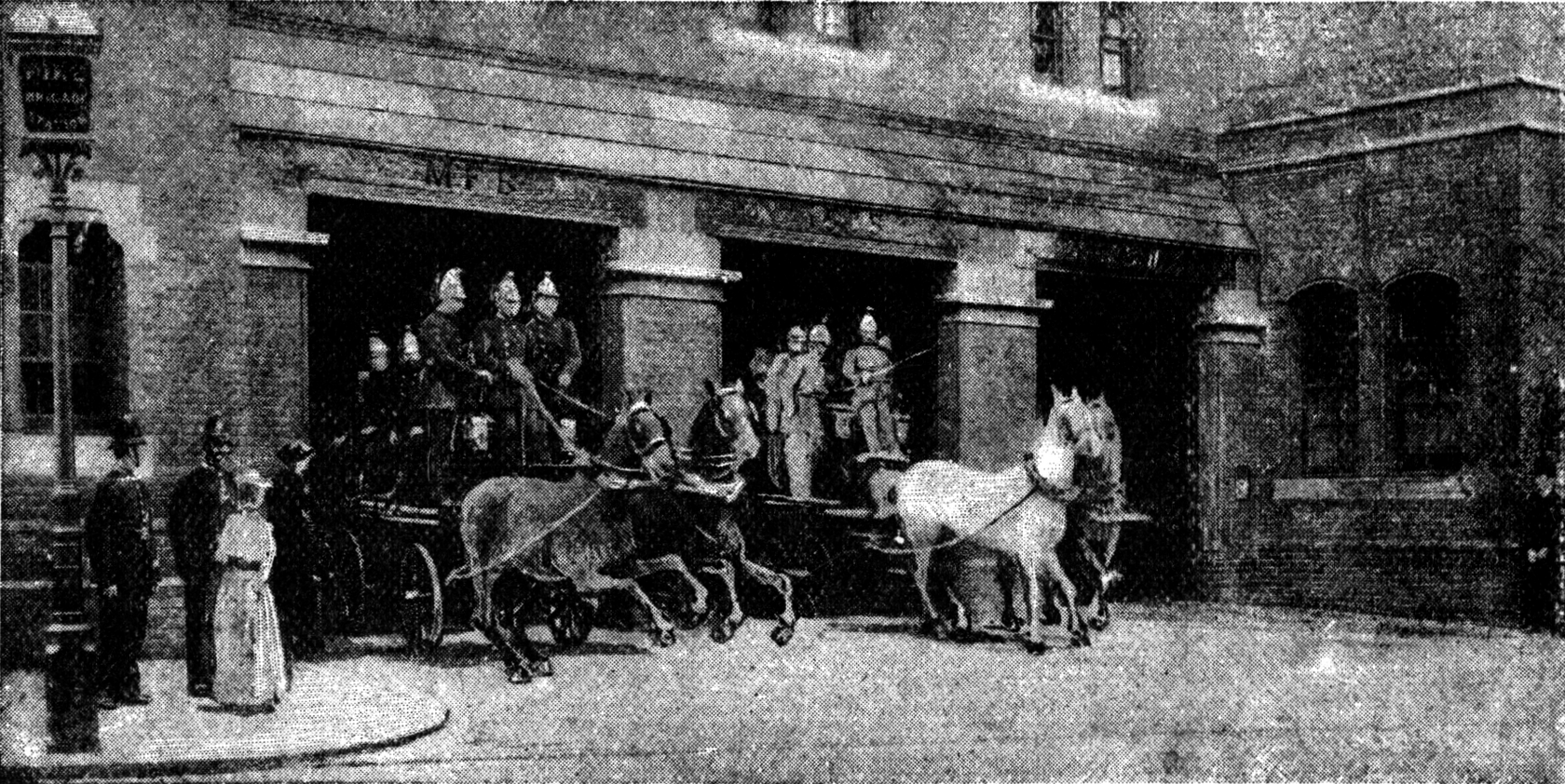

When any member of the brigade dies in the execution of his duty, it has been customary to accord the body a public funeral, and Ashford’s obsequies proved a very solemn and imposing ceremony. At eleven o’clock on December 14th, a large crowd assembled in Southwark Bridge Road, and detachments of officers and men had been drawn from various fire-stations, until nearly three hundred representatives of the brigade were present. A large number of policemen also joined the procession. It had a long way to traverse to Highgate Cemetery, where the burial took place. The coffin, of polished oak, was carried on a manual-engine, and covered by a Union Jack, the helmet of the deceased and a beautiful wreath subscribed for by members of the brigade being placed upon the flag. Three police bands preceded the coffin, and after it came mourning-coaches with the relatives of the deceased. Captain Shaw followed, leading, with Mr. Sexton Simonds, the second officer and the chairman of the brigade committee of the Board of Works; then came the large body of firemen with their flashing brass helmets; superintendents and engineers were also present, and the large contingent of police. Finally, followed six manual-engines in their vivid scarlet, and representatives of the salvage corps and of volunteer brigades. The procession marched slowly and solemnly, the bands playing the Dead March in “Saul.” And thus, with simple yet effective ceremony, the crushed and broken body was borne through London streets to its last resting-place.

It may be interesting to trace here the chief particulars of the fire, to illustrate the working of the brigade. Of the firemen watching on the premises, one had gone his round, when about one o’clock, on going on the stage, he saw the balcony ablaze. He aroused Hutchings, another fireman who slept at the theatre, and the two got a hydrant to work, there having been several fitted in the building; they also despatched a messenger to Chandos Street station, which is quite near. The fire proved too strong for the hydrant to quench it; and when the manual-engine from the station arrived, a fairly fierce fire was in progress.

Meantime, directly the alarm had been received at Chandos Street, it was, as is customary, sent on to the station of the superintendent of the district, and thence it was circulated to all the stations in the district, and also to headquarters. Captain Shaw was soon on the spot, and directed the operations in person. Of course, such a call as “The Alhambra Theatre alight!” would cause a number of engines to assemble; and in truth, they hurried from all points of the district: they came from Holloway and Islington, from St. Luke’s and Holborn. But soon “more aid” was telegraphed for; and then engines came flying from Westminster and Brompton, from Kensington and Paddington, even from Mile End and Shadwell in the far east, and from Rotherhithe, Deptford, and Greenwich across the Thames. In rapid succession, they thundered along the midnight streets, waking sleepers in their warm beds, and paused not until the excited horses were pulled up before the furious fire.

In fact, just within half an hour of the first call at Chandos Street station, twenty-four steamers were at work on the fire, and throwing water upon the flames from every possible point. Captain Shaw was assisted by his lieutenant, Mr. Sexton Simonds, and Superintendents Gatehouse and Palmer. The contents of the building were so inflammable, or the fire had obtained such a firm hold, that the enormous quantities of water thrown upon it appeared to exercise little or no effect. But at length, when the roof had fallen, the firemen seemed to gain somewhat on their enemy; and they turned their attention to the dwellings in Castle Street, and prevented the flames from spreading there. Finally, three hours after the outbreak, that is, about four in the morning, the fire was practically suppressed. Several of the surrounding buildings were damaged by fire and heat, and by smoke and water.

In the dim wintry dawn, the scene that slowly became revealed presented a remarkable spectacle. Looking at it from the stage door, the blackened front wall could be seen still standing, though the windows had gone, and within yawned a huge pit of ruin. Scorched remains of boxes and galleries, dressing-rooms and roof, all were here; while huge girders could be seen twisted and rent and distorted into all manner of curious shapes, which spoke more eloquently than words of the fearful heat which had been raging.

The value of strong iron doors, however, was demonstrated; for the paint-room had been shut off by these doors from the rest of the building, and the flames had not entered it.

But to turn to other relics in the museum. Here lies a terrible little collection,—a part of a tunic, a belt-buckle, an iron spanner, part of a blackened helmet, and part of a branch-pipe and nozzle. They are the memorials of a man who was burnt at his post.

Early in the afternoon of September 13th, 1889, an alarm was sent to the Wandsworth High Street fire-station. The upper part of a very high building in Bell Lane, occupied by Burroughs & Wellcome, manufacturing chemists, was found to be on fire. The time was then about a quarter-past two, and very speedily a manual-engine from the High Street station was on the spot.

A stand-pipe was at once utilized, and Engineer Howard, with two third-class firemen, named respectively Jacobs and Ashby, took the hose up the staircase to reach the flames. Unfortunately, the stairs were at the other end of the building, and the men had to go back along the upper floor to arrive at the point where the fire was burning.

Having placed his two men, Engineer Howard went for further assistance. Amid suffocating smoke, Jacobs and Ashby stood at their post, turning the water on the fire; and their efforts appeared likely to be successful, when suddenly, a great outburst of flame occurred behind them, cutting off their escape by the staircase.

It was a terrible position,—fire before and behind, and no escape but the window!

Both men rushed to a casement, and cried aloud, “Throw up a line!” The crowd below saw the men tearing at the window-bars and endeavouring to break them, while the fire rapidly spread towards them.

Could no help be given? Howard had endeavoured to rejoin the two men, and, finding this impracticable, turned to obtain external aid. The ladders on the engine were fixed together, but they fell far short of the high window. A builder’s ladder was added; but even this extension would not reach the two men caged up high above in such fearful peril.

A moment or two of dreadful suspense, and then the crowd burst forth into loud cheers. Ashby was seen to be forcing his way through the iron bars. He was small in stature, and his size was in his favour. By some means, perhaps scarcely known to himself, he dropped down to the top of the ladder and clung there, and finally, though very much burned, he reached the ground in safety.

But the other? Alas! his case was far different. It is supposed that the smoke overcame him, and that he fell on his face; but he was never seen alive again. Engines rattled up from all parts of London, and quantities of water were thrown on the flames, but to no effect so far as he was concerned. When the fire was subdued, and the men hastily made their way to the upper floor, they found only his charred remains. He had died at his post, the smoke suffocation, it may be hoped, rendering him insensible to pain.

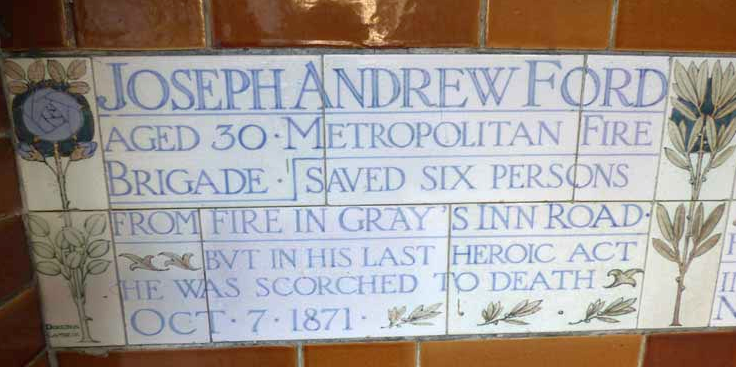

But an even more terrible accident happened to a fireman named Ford, in October, 1871. His death, after saving six persons, remains one of the most terrible in the annals of the brigade.

About two in the morning of October 7th, 1871, an alarm of fire reached the Holborn station. The call came from Gray’s Inn Road; and Ford, who had charge of the fire-escape, was soon at the scene of action. He found a fire raging in the house of a chemist at No. 98 in the road, and the inmates were crying for help at the windows.

Placing the escape against the building, he hurried to a window in one of the upper floors, and, assisted by a policeman, brought down five of the inhabitants in safety. Still there was one remaining, and frantic cries from a woman in a window above led him to rush up the escape once more. He had taken her from the building, and was conveying her down the escape, when a burst of flame belched out from the first floor and kindled the canvas “shoot” of the escape. In a second, both the fireman and the rescued woman were surrounded by fire.

Unable to hold her any longer, he dropped her to the ground, where she alighted without suffering any serious injury. But the fireman became entangled in the wire netting of the machine, and it held him there in its cruel grasp, in spite of all his struggles, while the fierce fire roasted him alive.

At length, by a desperate effort, he broke the netting, apparently by straining the rungs of the ladder; but he himself fell to the ground so heavily, that his helmet was quite doubled up, and its brasswork hurt his head severely. His clothes were burning as he lay on the pavement; but, happily, they were soon extinguished, and he was removed, suffering great agony, to the Royal Free Hospital in the Gray’s Inn Road. He lingered until eight o’clock on the evening of the same day, when he died.

He was only about thirty years of age, and had been four years in the brigade, where he bore a good character. A subscription was raised for his widow and two children, and his funeral was an imposing and solemn ceremony. The coffin was borne on a fire-engine drawn by four horses to Abney Park Cemetery, and was followed by detachments of firemen and of police.

It is a peculiarly sad feature of this case that, after saving so many lives, he should himself have succumbed, and that the very machine intended to save life should have been the cause of his death. At the inquest the jury added to their verdict the remark that, had the canvas been non-inflammable (means having been discovered to render fabrics non-inflammable), and had the machine been covered with wire gauze instead of the netting, Ford’s life might have been saved. Considerable improvements have been made in fire-escapes since then, and machines of various patterns are in use in the brigade; but, speaking generally, it may be said that the shoot, when used, is made of copper netting, which is, of course, non-inflammable.

Happily, all the brave deeds of the firemen do not meet with personal disaster. One brilliant summer afternoon in July, 1897, the Duke and Duchess of York were present at the annual review of the brigade on Clapham Common, and the Duchess pinned the silver medal for bravery on the breast of Third-class Fireman Arthur Whaley, and the good service medal was given to many members of the brigade. Whaley had saved two little boys from a burning building, and his silver medal is a highly-prized and honourable memorial of his gallant deed.

About one o’clock on the early morning of April 26th, 1897, a passer-by noticed that a coffee-house in Caledonian Road, North London, was on fire. Several policemen hurried to the spot; but in three minutes from the first discovery the place was in flames. The house was full of people. Mr. Bray, the occupier, was apparently the first inmate to notice the fire from within, and the others were soon aroused. The terrified people appeared at the windows, and, impelled by the cruel fire, threw themselves one after the other into the street below. They numbered Mr. and Mrs. Bray and four daughters; all except Mr. Bray appeared to be injured, and were taken to the hospital. Some one also threw a child into the street, and he was caught by one of the persons passing by.

And now up came the firemen with their escape from Copenhagen Street. Pitching it against the house, they hurried to the upper windows. From one of these they brought down a young woman, who was sadly burnt about the face, and she was sent also to the hospital. Penetrating still farther amid the smoke and flame, Arthur Whaley groped about, and found two lads asleep, and, bearing them out, saved their lives by means of the escape.

The fire did considerable damage before it was finally extinguished; but when the stand-pipes were got fully to work, the flames were quickly subdued. One of the daughters died from severe burns soon after her admission to the hospital, and it was afterwards found that a girl of fifteen had been unhappily suffocated in bed. But for the bravery of Whaley, the two little boys might have suffered the same sad fate….