Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Victorian Worthies, by G.H. Blore (published 1920). All spelling in the original.

The famous Napier brothers, Charles, George, and William, came of no mean parentage. Their father, Colonel the Hon. George Napier, of a distinguished Scotch family, was remarkable alike for physical strength and mental ability. In the fervour of his admiration his son Charles relates how he could ‘take a pewter quart and squeeze it flat in his hand like a bit of paper’. In height 6 feet 3 inches, in person very handsome, he won the admiration of others besides his sons. He had served in the American war, but his later years were passed in organizing work, and he showed conspicuous honesty and ability in dealing with Irish military accounts. One of his reforms was the abolition of all fees in his office, by which he reduced his own salary from £20,000 to £600 per annum, emulating the more famous act of the elder Pitt as Paymaster-general half a century before. Their mother, Lady Sarah Lennox, daughter of the Duke of Richmond, had been a reigning toast in 1760. She had even been courted by George III, and might have been handed down to history as the mother of princes. In her old age she was more proud to be the mother of heroes; and her letters still exist, written in the period of the great wars, to show how a British mother could combine the Spartan ideal with the tenderest personal affection.

Their father’s appointment involved residence in Ireland from 1785 onwards, and the boys passed their early years at Celbridge in the neighbourhood of Dublin. Here they were far from the usual amusements and society of the time, but they were fortunate in their home circle and in the character of their servants, and they learnt to cherish the ancient legends of Ireland and to pick up everything that could feed their innate love of adventure and romance. Close to their doors lived an old woman named Molly Dunne, who claimed to be one hundred and thirty-five years of age, and who was ready to fill the children’s ears with tales of past tragedies whenever they came to see her. Sir William Napier tells us how she was ‘tall, gaunt, and with high sharp lineaments, her eyes fixed in their huge orbs, and her tongue discoursing of bloody times: she was wondrous for the young and fearful for the aged’.

Instead of class feeling and narrow interests the boys developed early a great sympathy for the poor, and a capacity for judging people independently of rank. Charles Napier himself, born in Whitehall, was three years old when they moved to Ireland. He was a sickly child, the one short member of a tall family, but equal to any of them in courage and resolution. His heroism in endurance of pain was put to a severe test when he broke his leg at the age of seventeen. It was twice badly set. He was threatened first by the entire loss of it, next with the prospect of a crooked leg, but he bore cheerfully the most excruciating torture in having it straightened by a series of painful experiments, and in no long time he recovered his activity. In the army he showed his strength of will by rigid abstinence from drinking and gambling, no easy feat in those days; and he learned by his father’s example to control all extravagance and to live contentedly on a small allowance. His earliest enthusiasm among books was for Plutarch’s Lives, the favourite reading of so many great commanders. He had many outdoor tastes: riding, fishing, and shooting, and he was soon familiar with the country-side. There was no need of classes or prizes to stimulate his reading, no need of organized games to provide an outlet for his energies or to fill his leisure time.

The confidence that his father had in the training of his sons is best shown by the early age at which he put them in responsible positions. Charles actually received a commission in the 33rd Regiment at the age of twelve, but he did not see service till he was seventeen. Meanwhile the young ensign continued his schooling from his father’s house at Celbridge, to which he and his brother returned every evening, sometimes in the most unconventional manner. Celbridge, like other Irish villages, had its pigs. The Irish pig is longer in the leg and more active than his English cousin, and the Napier boys would be seen careering along at a headlong pace on these strange mounts, with a cheering company of village boys behind them. They were Protestants among older Roman Catholic comrades, but they soon became the leaders in the school, and Charles, despite his youth and small stature, was chosen to command a school volunteer corps at the age of fourteen. At seventeen he joined his regiment at Limerick, and for six or seven years he led the life of a soldier in various garrison towns of southern England, fretting at inaction, learning what he could, and welcoming any chance of increased work and danger. At this time his enthusiasm for soldiering was very variable. In a letter written in 1803 he makes fun of the routine of his profession, as he was set to practise it, and ends up, ‘Such is the difference between a hero of the present time and the idea of one formed from reading Plutarch! Yet people wonder I don’t like the army!’

But this was a passing mood. When stirring events were taking place, no one was more full of ardour, and when he came under such a general as Sir John Moore he expressed himself in a very different tone. In 1805 Moore was commanding at Hythe, and Charles Napier’s letters are aglow with enthusiasm for the great qualities which he showed as an administrator and army reformer. Like Wolseley seventy or eighty years later, Moore had the gift of finding the best among his subalterns and training them in his own excellences. After his own father there was no one who had so much influence as Moore in the making of Charles Napier. In 1808 he sailed for the Peninsula with the rank of major, commanding the 50th Regiment in the colonel’s absence; he took an active part in Moore’s famous retreat at Coruña, and in the battle was taken prisoner after conduct of the greatest gallantry in leading his regiment under fire. Two months later he was released and again went to the front. In 1810 and 1811 he and his brothers George and William were fighting under Wellington, and were all so frequently wounded that the family fortunes became a subject of common talk. On more than one occasion Wellington himself wrote to Lady Sarah to inform her of the gallantry and misfortunes of her sons. At Busaco Charles had his jaw broken and was forced to retire into hospital at Lisbon. In his haste to rejoin the army, which he did when only half convalescent, he accomplished the feat of riding ninety miles on one horse in a single day; and in the course of his ride met two of his brothers being carried down, wounded, to the base. But in 1811 promotion withdrew Charles Napier from the Peninsula. A short command in Guernsey was followed by another in Bermuda, which involved him in the American war. He had little taste for warfare with men of the same race as himself, and was heartily glad to exchange back to the 50th in 1813, and to return to England. He started out as a volunteer to share in the campaign of Waterloo, but all was over before he could join the army in Flanders, and this part of his soldiering career ended quietly. He had received far more wounds than honours, and might well have been discouraged in the pursuit of his profession.

But here we can put to the test how far Napier’s expressions of distaste for the service affected his conduct. He chafed at the inactivity of peace; but instead of abandoning the army for some more profitable career, he used his enforced leisure to prepare for further service and to extend his knowledge of political and military history. He spent the greater part of three years at the Military College, then established at Farnham, varying his professional studies with sallies into the domain of politics, and as a result he developed marked Radical views which he held through life. His note-books show a splendid grasp of principles and a close attention to facts; they range from the enforcing of the death penalty for marauding to the details of cavalry-kit. His Spartan regime became famous in later years; even now he prescribed a strict rule, ‘a cloak, a pair of shoes, two flannel shirts, and a piece of soap—these, wrapped up in an oil-skin, must go in the right holster, and a pistol in the left.’ He took no opinions at second hand, but studied the best authorities and thought for himself; he was as thorough in self-education as the famous Confederate general ‘Stonewall’ Jackson, who every evening sat for an hour, facing a blank wall and reviewing in his mind the subjects which he had read during the day.

No opportunity for reaping the fruit of these studies and exercising his great gifts was given him till May 1819. Then he was appointed to the post of inspecting-officer in the Ionian Islands; and in 1822 he was appointed Military Resident in Cephalonia, the largest of these islands, a pile of rugged limestone hills, scantily supplied with water, and ruined by years of neglect and the oppression of Turkish pashas. So began what was certainly the happiest, and perhaps the most fruitful, period in Charles Napier’s life. It was not strictly military work, but, without the authority which his military rank gave him and without the despotic methods of martial law, little could have been achieved in the disordered state of the country. The whole episode is a good example of how a well-trained soldier of original mind can, when left to himself, impress his character on a semi-civilized people, and may be compared with the work of Sir Harry Smith in South Africa, or Sir Henry Lawrence in the Punjab. The practical reforms which he initiated in law, in commerce, in agriculture, are too numerous to mention. ‘Expect no letters from me’, he writes to his mother, ‘save about roads. No going home for me: it would be wrong to leave a place where so much good is being done…. My market-place is roofed. My pedestal is a tremendous job, but two months more will finish that also. My roads will not be finished by me.’ And again, ‘I take no rest myself and give nobody else any.’ To his superiors he showed himself somewhat impracticable in temper, and he was certainly exacting to his subordinates, though generous in his praise of those who helped him. He was compassionate to the poor and vigorous in his dealings with the privileged classes; and he gave the islanders an entirely new conception of justice. When he quitted the island after six years of office he left behind him two new market-places, one and a half miles of pier, one hundred miles of road largely blasted out of solid rock, spacious streets, a girls’ school, and many other improvements; and he put into the natives a spirit of endeavour which outlived his term of office. One sign of the latter was that, after his departure, some peasants yearly transmitted to him the profits of a small piece of land which he had left uncared for, without disclosing the names of those whose labours had earned it.

During this period, in visits to Corinth and the Morea, he worked out strategic plans for keeping the Turks out of Greece. He also made friends with Lord Byron, who came out in 1823 to help the Greek patriots and to meet his death in the swamps of Missolonghi. Byron conceived the greatest admiration for Napier’s talents and believed him to be capable of liberating Greece, if he were given a free hand. But this was not to be. Reasons of State and petty rivalries barred the way to the appointment of a British general, though it might have set the name of Napier in history beside those of Bolivar and Garibaldi; for he would have identified himself heart and soul with such a cause, and, in the opinion of many good judges, would have triumphed over the difficulties of the situation.

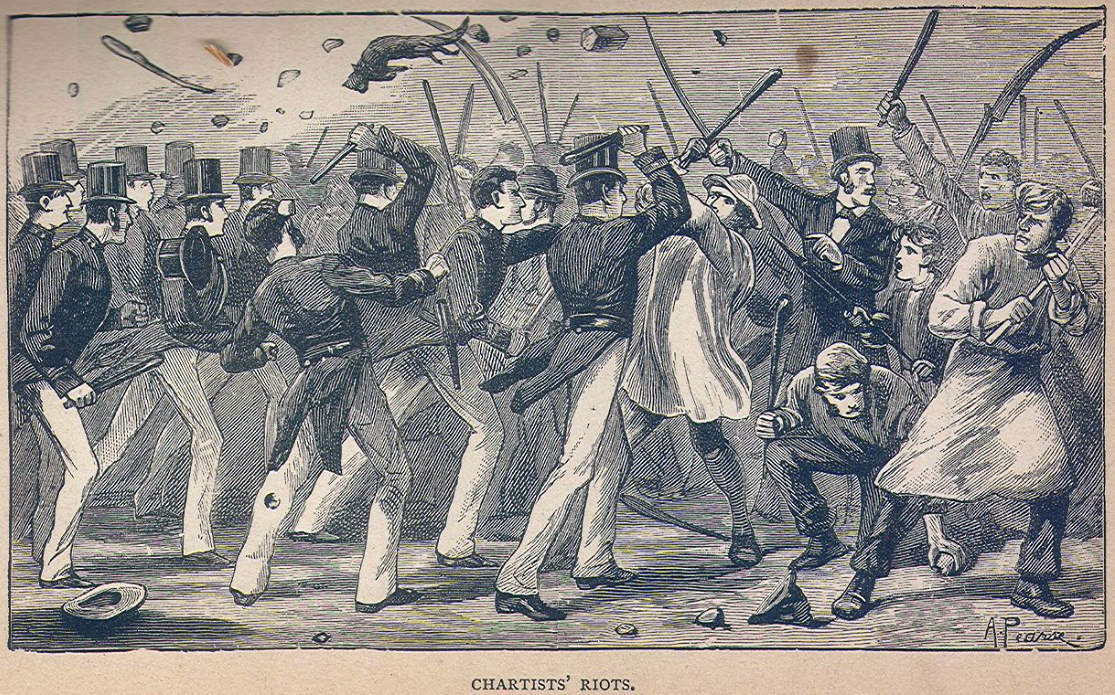

From 1830 to 1839 there is little to narrate. The gifts which might have been devoted to commanding a regiment, to training young officers, or to ruling a distant province, were too lightly rated by the Government, and he spent his time quietly in England and France educating his two daughters, interesting himself in politics, and continuing to learn. It was the political crisis in England which called him back to active life. The readjustment of the labour market to meet the use of machinery, and the occurrence of a series of bad harvests had caused widespread discontent, and the Chartist movement was at its height in 1839. Labourers and factory owners were alarmed; the Government was besieged with petitions for military protection at a hundred points, and all the elements of a dangerous explosion were gathered together. At this critical time Charles Napier was offered the command of the troops in the northern district, and amply did he vindicate the choice. By the most careful preparation beforehand, by the most consummate coolness in the moment of danger, he rode the storm. He saw the danger of billeting small detachments of troops in isolated positions; he concentrated them at the important points. He interviewed alarmed magistrates, and he attended, in person and unarmed, a large gathering of Chartists. To all he spoke calmly but resolutely. He made it clear to the rich that he would not order a shot to be fired while peaceful measures were possible; he made it equally clear to the Chartists that he would suppress disorder, if it arose, promptly and mercilessly. With only four thousand troops under his command to control all the industrial districts of the north, Newcastle and Manchester, Sheffield and Nottingham, he did his work effectually without a shot being fired. ‘Ars est celare artem’: and just because of his success, few observers realized from how great a danger the community had been preserved.

Thus he had proved his versatile talents in regimental service in the Peninsula, in the reclamation of an eastern island from barbarism, and in the control of disorder at home. It was not till he had reached the age of sixty that he was to prove these gifts in the highest sphere, in the handling of an army in the field and in the direction of a campaign. But the offer of a command in India roused his indomitable spirit, the more so as trouble was threatening on the north-west frontier. An ill-judged interference in Afghānistān had in 1841 caused the massacre near Kābul of one British force: other contingents were besieged in Jalālābād and Ghazni, and were in danger of a similar fate, and the prestige of British arms was at its lowest in the valley of the Indus. Lord Ellenborough, the new Viceroy, turned to Charles Napier for advice, and in April 1842 he was given the command in Upper and Lower Sind, the districts comprising the lower Indus valley. It was his first experience of India and his first command in war. He was sixty years old and he had not faced an enemy’s army in the field since the age of twenty-five. As he said, ‘I go to command in Sind with no orders, no instructions, no precise line of policy given! How many men are in Sind? How many soldiers to command? No one knows!… They tell me I must form and model the staff of the army altogether! Feeling myself but an apprentice in Indian matters, I yet look in vain for a master.’ But the years of study and preparation had not been in vain, and responsibility never failed to call out his best qualities. It was not many months before British officers and soldiers, Baluch chiefs and Sindian peasants owned him as a master—such a master of the arts of war and peace as had not been seen on the Indus since the days of Alexander the Great.

First, like a true pupil of Sir John Moore, he set to work thoroughly to drill his army. He experimented in person with British muskets and Marāthā matchlocks, and reassured his soldiers on the superiority of the former. He experimented with rockets to test their efficiency; and, with his usual luck in the matter of wounds, he had the calf of his leg badly torn by one that burst. He would put his hand to any labour and his life to any risk, if so he might stir the activity of others and promote the cause. He convinced himself, by studying the question at first hand, that the Baluch Amīrs, who ruled the country, were not only aliens but oppressors of the native peasantry, not only ill-disposed to British policy, but actively plotting with the hill-tribes beyond the Indus, and at the right moment he struck.

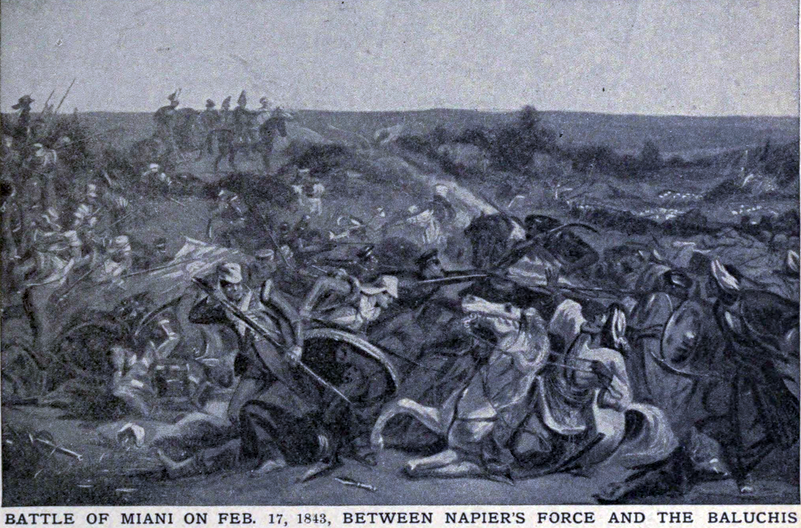

The danger of the situation lay in the great extent of the country, in the difficulty of marching in such heat amid the sand, and in the possibility of the Amīrs escaping from his grasp and taking refuge in fortresses in the heart of the desert, believed to be inaccessible. His first notable exploit was a march northwards one hundred miles into the desert to capture Imāmghar; his last, crowning a memorable sixteen days, was a similar descent upon Omarkot, which lay one hundred miles eastward beyond Mīrpur. These raids involved the organization of a camel corps, the carrying of water across the desert, and the greatest hardships for the troops, all of which Charles Napier shared uncomplainingly in person. Under his leadership British regiments and Bombay sepoys alike did wonders. Who could complain for himself when he saw the spare frame of the old general, his health undermined by fever and watches, his hooked nose and flashing eye turned this way and that, riding daily at their head, prepared to stint himself of all but the barest necessaries and to share every peril? He had begun the campaign in January; the crowning success was won on April 6. Between these dates he fought two pitched battles at Miāni and Dabo, and completely broke the power of the Amīrs.

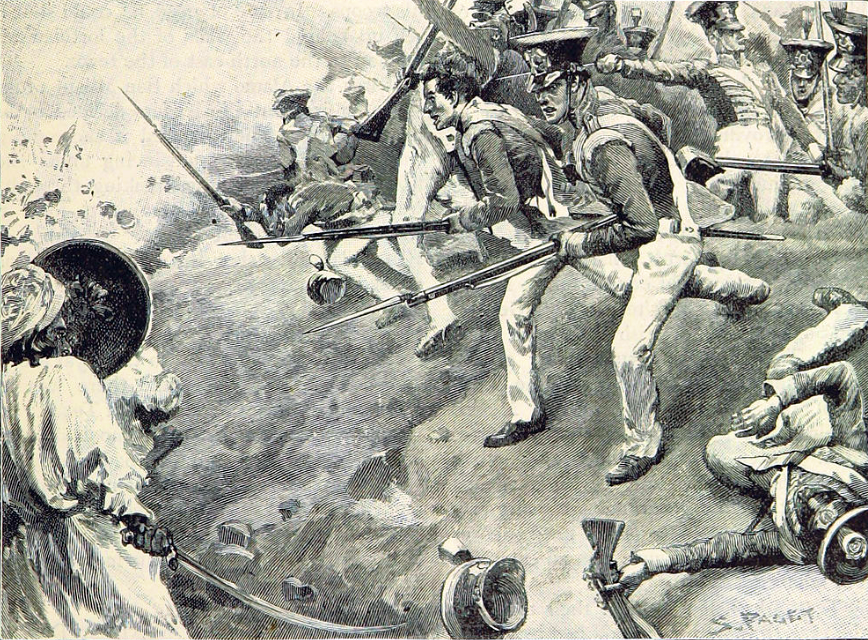

Miāni (February 17, 1843) was the most glorious day in his life. With 2,400 troops, of whom barely 500 were Europeans, he attacked an army variously estimated between 20,000 and 40,000. Drawn up in a position, which they had themselves chosen, on the raised bank of a dry river bed, the Baluchī seemed to have every advantage on their side. But the British troops, advancing in echelon from the right, led by the 22nd Regiment, and developing an effective musketry fire, fought their way up to the outer slope of the steep bank and held it for three hours. Here the 22nd, with the two regiments of Bombay sepoys on their left, trusting chiefly to the bayonet, but firing occasional volleys, resisted the onslaught of Baluchī swordsmen in overwhelming numbers. During nearly all this time the two lines were less than twenty yards apart, and Napier was conspicuous on horseback riding coolly along the front of the British line. The matchlocks, with which many of the Baluchī were armed, seem to have been ineffective; their national weapon was the sword. The tribesmen were grand fighters but badly led. They attacked in detachments with no concerted action. For all that, the British line frequently staggered under the weight of their courageous rushes, and irregular firing went on across the narrow gap. Napier says, ‘I expected death as much from our own men as from the enemy, and I was much singed by our fire—my whiskers twice or thrice so, and my face peppered by fellows who, in their fear, fired over all heads but mine, and nearly scattered my brains’. Not even Scarlett at Balaclava had a more miraculous escape. This exposure of his own person to risk was not due to mere recklessness. In his days at the Royal Military College he had carefully considered the occasions when a commander must expose himself to get the best out of his men; and from Coruña to Dabo he acted consistently on his principles. Early in the battle he had cleverly disposed his troops so as to neutralize in some measure the vast numerical superiority of the enemy; his few guns were well placed and well served. At a critical moment he ordered a charge of cavalry which broke the right of their position and threatened their camp; but the issue had to be decided by hard fighting, and all depended on the morale which was to carry the troops through such a punishing day.

The second battle was fought a month later at Dabo, near Hyderābād. The most redoubtable of the Amīrs, Sher Muhammad, known as ‘the Lion of Mīrpur’, had been gathering a force of his own and was only a few miles distant from Miāni when that battle was fought. Napier could have attacked him at once; but, to avoid bloodshed, he was ready to negotiate. ‘The Lion’ only used the respite to collect more troops, and was soon defying the British with a force of 25,000 men, full of ardour despite their recent defeat. Indeed Napier encouraged their confidence by spreading rumours of the terror prevailing in his own camp. He did not wish to exhaust his men needlessly by long marches in tropical heat; so he played a waiting game, gathering reinforcements and trusting that the enemy would soon give him a chance of fighting. This chance came on March 24, and with a force of 5,000 men and 19 guns Napier took another three hours to win his second battle and to drive Sher Muhammad from his position with the loss of 5,000 killed. The British losses were relatively trifling, amounting to 270, of whom 147 belonged to the sorely tried 22nd Regiment. They were all full of confidence and fought splendidly under the general’s eye. ‘The Lion’ himself escaped northwards, and two months of hard marching and clever strategy were needed to prevent him stirring up trouble among the tribesmen. The climate took toll of the British troops and even the general was for a time prostrated by sunstroke; but the operations were successful and the last nucleus of an army was broken up by Colonel Jacob on June 15. Sher Muhammad ended his days ignominiously at Lahore, then the capital of the Sikhs, having outlived his fame and sunk into idleness and debauchery.

Thus in June 1843 the general could write in his diary: ‘We have taught the Baluch that neither his sun nor his desert nor his jungles nor his nullahs can stop us. He will never face us more.’ But Charles Napier’s own work was far from being finished. He had to bind together the different elements in the province, to reconcile chieftain and peasant Baluch, Hindu, and Sindian, to living together in amity and submitting to British rule; and he had to set up a framework of military and civilian officers to carry on the work. He held firmly the principle that military rule must be temporary. For the moment it was more effective; but it was his business to prepare the new province for regular civil government as soon as was feasible. He showed his ingenuity in the personal interviews which he had with the chieftains; and the ascendancy which he won by his character was marked. Perhaps his qualities were such as could be more easily appreciated by orientals than by his own countrymen, for he was impetuous, self-reliant, and autocratic in no common degree. He was only one of a number of great Englishmen of this century whose direct personal contact with Eastern princes was worth scores of diplomatic letters and paper constitutions. Such men were Henry Lawrence, John Nicholson, and Charles Gordon; in them the power of Great Britain was incarnate in such a form as to strike the imagination and leave an ineffaceable impression. Many of the Amīrs wished to swear allegiance to a governor present in the flesh rather than to the distant queen beyond the sea, so strongly were they impressed by Napier’s personal character.

He did not forget his own countrymen, least of all that valued friend ‘Thomas Atkins’ and his comrade the sepoy. By the erection of spacious barracks he made the soldier’s life more pleasant and his health more secure; and in a hundred other ways he showed his care and affection for them. In return few British generals have been so loved by the rank and file. He also gave much thought to material progress, to strengthening the fortress of Hyderābād, to developing the harbour at Karāchi, and, above all, to enriching the peasants by irrigation schemes. It was the story of Cephalonia on a bigger scale; but Napier was now twenty years older, overwhelmed with work, and he could give less attention to details. He did his best to find subordinates after his own heart, men who would ‘scorn delights and live laborious days’. ‘Does he wear varnished boots?’ was a typical question that he put to a friend in Bombay, when a new engineer was commended to him. His own rewards were meagre. The Grand Cross of the Bath and the colonelcy of his favourite regiment, the 22nd, were all the recognition given for a campaign whose difficulties were minimized at home because he had mastered them so triumphantly.

Two other achievements belong to the period of his government of Sind. The campaign against the tribes of the Kachhi Hills, to the north-west of his province, rendered necessary by continued marauding, shows all his old mastery of organization. Any one who has glanced into Indian history knows the danger of these raids and the bitter experience which our Indian army has gained in them. In less than two months (January-March 1845) Napier had led five thousand men safely over burning deserts and through most difficult mountain country, had by careful strategy driven the marauders into a corner, forcing them to surrender with trifling loss, and had made an impression on the hill chieftains which lasted for many a year. This work, though slighted by the directors of the Company, received enthusiastic praise from such good judges of war as Lord Hardinge and the Duke of Wellington. The second emergency arose when the first Sikh war broke out in the Punjab. Napier felt so confident in the loyalty of his newly-pacified province that within six weeks he drew together an army of 15,000 men, and took post at Rohri, ready to co-operate against the Sikhs from the south, while Lord Hardinge advanced from the east. Before he could arrive, the decisive battle had been fought, and all he was asked to do was to assist in a council of war at Lahore. The mistakes made in the campaign had been numerous. No one saw them more clearly than Napier, and no one foretold more accurately the troubles which were to follow. For all that, he wrote in generous admiration of Lord Hardinge the Viceroy and Lord Gough the Commander-in-Chief at a time when criticism and personal bitterness were prevalent in many quarters.

After this he returned to Sind with health shattered and a longing for rest. He continued to work with vigour, but his mind was set on resignation; and the bad relations which had for years existed between him and the directors embittered his last months. No doubt he was impatient and self-willed, inclined to take short cuts through the system of dual control and to justify them by his own single-hearted zeal for the good of the country. But the directors had eyes for all the slight irregularities, which are inevitable in the work of an original man, and failed entirely to estimate the priceless services that he rendered to British rule. In July 1847 he resigned and returned to Europe; but even now the end was not come. ‘The tragedy must be re-acted a year or two hence,’ he had written in March 1846, seeing clearly that the Sikhs had not been reconciled to British rule. In February 1849 the directors were forced by the national voice to send him out to take supreme military command and to retrieve the disasters with which the second Sikh war began. They were very reluctant to do so, and Napier himself had little wish for further exertions in so thankless a service. But the Duke of Wellington himself appealed to him, the nation spoke through all its organs, and he could not put his own wishes in the scale against the demands of public service.

He made all speed and reached Calcutta early in May, but he found no enemy to fight. The issue had been decided by Lord Gough and the hard fighting of Chiliānwāla. He had been cheated by fortune, as in 1815, and he never knew the joy of battle again. He was accustomed to settle everything as a dictator; he found it difficult to act as part of an administrative machine. He was unfamiliar with the routine of Indian official life, and he was now growing old; he was impatient of forms, impetuous in his likes and dislikes, outspoken in praise and condemnation. His relations with the masterful Viceroy, Lord Dalhousie, were soon clouded; and though he delighted in the friendship of Colin Campbell and many other able soldiers, he was too old to adapt himself to new men and new measures. In 1850 the rumblings of the storm, which was to break seven years later, could already be heard, and Napier had much anxiety over the mutinous spirit rising in the sepoy regiments. He did his best to go to the bottom of the trouble and to establish confidence and friendly relations between British and natives, but he had not time enough to achieve permanent results, and he was often fettered by the regulations of the political service. His predictions were as striking now as in the first Sikh war; but he was not content to predict and to sit idle. He was unwearied in working for the reform of barracks, though his plans were often spoiled by the careless execution of others. He was urgent for a better tone among regimental officers and for more consideration on their part towards their soldiers. If more men in high position had similarly exerted themselves, the mutiny would have been less widespread and less fatal. His resignation was due to a dispute with Lord Dalhousie about the sepoys’ pay. Napier acted ultra vires in suspending on his own responsibility an order of the Government, because he believed the situation to be critical, while the Viceroy refused to regard this as justified. His departure, in December 1850, was the signal for an outburst of feeling among officers, soldiers, and all who knew him. His return by way of Sind was a triumphal progress.

He had two years to live when he set foot again in England, and most of this was spent at Oaklands near Portsmouth. His health had been ruined in the public service; but he continued to take a keen interest in passing events and to write on military subjects to Colin Campbell and other friends. At the same time he devoted much of his time to his neighbours and his farm. In 1852 he attended as pall-bearer at the Duke of Wellington’s funeral; his own was not far distant. His brother, Sir William, describes the last scene thus: ‘On the morning of August 29th 1853, at 5 o’clock, he expired like a soldier on a naked camp bedstead, the windows of the room open and the fresh air of Heaven blowing on his manly face—as the last breath escaped, Montagu McMurdo (his son-in-law), with a sudden inspiration, snatched the old colours of the 22nd Regiment, the colour that had been borne at Miāni and Hyderābād, and waved them over the dying hero. Thus Charles Napier passed from the world.’

He was a man who roused enthusiastic devotion and provoked strong resentment. Like Gordon, he was a man who could rule others, but could not be ruled; and his official career left many heart-burnings behind. His equally passionate brother, Sir William, who wrote his life, took up the feud as a legacy and pursued it in print for many years. It is regrettable that such men cannot work without friction; but in all things it was devotion to the public service, and not personal ambition, that carried Charles Napier to such extremes. From his youth he had trained himself to such a pitch of self-denial and ascetic rigour that he could not make allowance for the frailties of the average man. His keen eye and swift brain made him too impatient of the shortcomings of conscientious officials. He was ready to work fifteen hours a day when the need came; he was able to pierce into the heart of a matter while others would be puzzling round the fringes of it. Rarely in his long and laborious career did an emergency arise capable of bringing out all his gifts; and his greatest exploits were performed on scenes unfamiliar to the mass of his fellow countrymen. But a few opinions can be given to show that he was rated at his full value by the foremost men of the day.

Perhaps the most striking testimony comes from one who never saw him; it was written three years after his death, when his brother’s biography appeared. It was Carlyle, the biographer of Cromwell and Frederick the Great, the most famous man of letters of the day, who wrote in 1856: ‘The fine and noble qualities of the man are very recognizable to me; his piercing, subtle intellect turned all to the practical, giving him just insight into men and into things; his inexhaustible, adroit contrivances; his fiery valour; sharp promptitude to seize the good moment that will not return. A lynx-eyed, fiery man, with the spirit of an old knight in him; more of a hero than any modern I have seen for a long time.’ A second tribute comes from one who had known him as an officer and was a supreme judge of military genius. Wellington was not given to extravagant words, but on many occasions he expressed himself in the warmest terms about Napier’s talents and services. In 1844, speaking of the Sind campaign in the House of Lords, he said: ‘My Lords, I must say that, after giving the fullest consideration to these operations, I have never known any instance of an officer who has shown in a higher degree that he possesses all the qualities and qualifications necessary to enable him to conduct great operations.’ In the House of Commons at the same time Sir Robert Peel—the ablest administrative statesman of that generation, who had read for himself some of Napier’s masterly dispatches—said: ‘No one ever doubted Sir Charles Napier’s military powers; but in his other character he does surprise me—he is possessed of extraordinary talent for civil administration.’ Again, he speaks of him as ‘one of three brothers who have engrafted on the stem of an ancient and honourable lineage that personal nobility which is derived from unblemished private character, from the highest sense of personal honour, and from repeated proofs of valour in the field, which have made their name conspicuous in the records of their country’.

Indifferent as Charles Napier was to ordinary praise or blame, he would have appreciated the words of such men, especially when they associated him with his brothers; but perhaps he would have been more pleased to know how many thousands of his humble fellow countrymen walked to his informal funeral at Portsmouth, and to know that the majority of those who subscribed to his statue in Trafalgar Square were private soldiers in the army that he had served and loved.