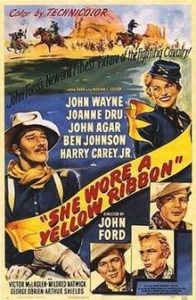

In continuing with my old movie watching series, I viewed the next film in the “Cavalry Series,” She Wore a Yellow Ribbon. This is another John Ford classic, starring John Wayne (in what some say is his finest acting performance), along with other Hollywood conservatives Joanne Dru, Ben Johnson, and Victor McLaglen. In a sense, these movies (Fort Apache, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, and Rio Grande) are a series, with some common characters, while having some distinct differences (for example, John Wayne is in all three films, but plays two – maybe three – different characters.as he has the same name in the first and third movies, but the name is spelled differently; McLagen, in this film, plays Sgt. Quincannon, and as he does in the third movie, but a character by the same name is played by Dick Foran in the first one). Perhaps it is easier to just view them all as separate, but related movies, rather than considering them as sequels. In any event, they all provide for great entertainment and offer some good lessons to ponder.

In this particular film, the concept of journey is front and center. It is presented in varying layers. We get to see an aging cavalry officer, Nathan Brittles (Wayne), nearing retirement (as is his close friend and fellow soldier of many years, Sgt. Quincannon). Their military journey is coming to a close. Their career journeys are winding down. We also find a young woman, Miss Dandridge (Dru), moving from girlhood to womanhood, navigating the sticky realm of intimate relationships with young officers. Throughout the movie, we see children (who have lost their parents), young adults entering into maturity (both career-wise and in relastionships), and older adults moving through middle age. In all of these individual stories, people are moving from one phase of life into another.

In this particular film, the concept of journey is front and center. It is presented in varying layers. We get to see an aging cavalry officer, Nathan Brittles (Wayne), nearing retirement (as is his close friend and fellow soldier of many years, Sgt. Quincannon). Their military journey is coming to a close. Their career journeys are winding down. We also find a young woman, Miss Dandridge (Dru), moving from girlhood to womanhood, navigating the sticky realm of intimate relationships with young officers. Throughout the movie, we see children (who have lost their parents), young adults entering into maturity (both career-wise and in relastionships), and older adults moving through middle age. In all of these individual stories, people are moving from one phase of life into another.

Beyond the personal journeys, the warfare between the Native Americans and Westward-pushing Americans begins to change. No longer are the tribes isolated from and antagonistic towards one another, but are joining forces to combat a common enemy. This necessitates a change in the way the Americans face their opponents. This is highlighted by a scene toward the end of the movie when Cpt. Brittles meets with Chief Pony That Walks to broker peace, but the aged Indian is unable to do that, as the young warriors no longer listen to him, and he offers to go with the retiring officer to hunt buffalo together and let the young men kill themselves (as many from both sides will die when the battle begins).

Finally, on a literal level, the plot revolves around the journey that Cpt. Brittle’s troops take to find and stop the Indians, while also delivering women passengers to a nearby post to catch a stagecoach to safety. Honestly, it has a similar feel to Mad Max: Fury Road, where a caravan leaves from its home base toward a destination, only to have to return.

So we see journeys from multiple viewpoints, and as this was a movie from the Golden Age of Hollywood, each has a positive resolution. I won’t give it all away, but suffice it to say that major battles are averted by the ingenuity of Brittles, relationships are settled, and everyone gets what they want in the end.

There were a few poignant moments that stood out. The movie takes place in 1876, immediately after Gen. Custer was routed at Little Big Horn. Many of the soldiers are former Confederates, who have gone on to join with their former foes. This is a major subplot of the movie, showing that old enemies can become friends and compatriots. It signals healing that is taking place. In one scene, as a wounded trooper, Pvt. Smith, nears death, he calls out for “Capt. Tyree.” Tyree is a sergeant (played by Ben Johnson), and Capt. Brittles orders him to respond to the dying trooper. It turns out that Pvt. Smith had been a General Clay in the Confederate army, and Tyree had been a Captain under his command. When they lay Pvt Smith to rest, a small Confederate Battle Flag is placed upon his coffin, and all mourn him, Yankee and Southerner alike.

The desire for peace is part of the journey motif. Not only are these old American divisions being healed, but the older Indians also desire peace, rather than bloodshed, pointing to the wisdom that comes with age. While this is a Hollywood re-interpretation of history, it seems to fit well within the era in which it was filmed, coming a few years after World War II, and the need to find peace and healing after a long and bloody war. Post-WWII, a new foe arose, Communism, but perhaps by using prudent strategy and tactics, all out war could be avoided, and combat kept to a minimum. Of course, we know that this did happen, and our Post-Cold War hindsight shows us the wisdom in making good decisions to avoid open conflict.

The desire for peace is part of the journey motif. Not only are these old American divisions being healed, but the older Indians also desire peace, rather than bloodshed, pointing to the wisdom that comes with age. While this is a Hollywood re-interpretation of history, it seems to fit well within the era in which it was filmed, coming a few years after World War II, and the need to find peace and healing after a long and bloody war. Post-WWII, a new foe arose, Communism, but perhaps by using prudent strategy and tactics, all out war could be avoided, and combat kept to a minimum. Of course, we know that this did happen, and our Post-Cold War hindsight shows us the wisdom in making good decisions to avoid open conflict.

Another interesting element was the clear presentation of the difficulty of travel in those days. Often, when we think of wagons moving through the old west, we picture large wagon trains slowly meandering across flat and dusty plains, and surely that did happen on occasion, but often the trails were not flat or easy to traverse. John Ford offers a glimpse of that, as the Cavalry troop moves on their literal journey, with a wagon in tow. Often, the wagon must go up and down steep, rocky, and barely navigable landscapes. In fact, I kept expecting the wagon to overturn, and at one point, several items spilled from the back of the vehicle as it moved up a steep embankment. It was a good reminder that those brave folks who made these types of journeys had to be good problem-solvers, finding ways to accommodate diffcult obstacles.

My favorite recurring element in the film was Brittle’s insistence that one should never apologize, as it showed a weakness of character. In that, he simply meant that you do what you think is best. Look at the situation, weigh the evidence, and then proceed. If it turns out you were wrong, or unsuccessful, then you can take solace in that you have learned something. As long as you do what you are convinced is the right thing to do, then you have nothing for which to apologize.

There was actually little fighting in the movie, as this was a film about journeys and peace, not war and death. It was a reminder that there are ways to resolve conflicts that do not lead to violence. Whether we focus on the obvious conflict between Indians and Cavalry, or between two young officers vying for the attention of a girl, overt violence is not the only option. In fact, the most violent scene involves Sgt. Quincannon being tricked into breaking regulations, whereby he is ordered to the brig, but he won’t go peacefully, besting seven other soldiers in a bar fight (Brittles had enacted this ruse to keep Quincannon safe during his last few weeks on active duty, so he could survive to retire). In a sense, a small act of violence is used to preserve a long-term peace.

Perhaps a subtle message is not just that we are all moving toward a final goal, but that the journey itself is worth savoring. It is not always pleasant or enjoyable, but those experiences make up the moments of our lives and should be appreciated. No matter where the journey leads, whether to new vistas or back to where we started, it provides us with meaning and purpose, and sometimes the end result is a nice surprise, and opens up opportunities for even more journeys.

3.5