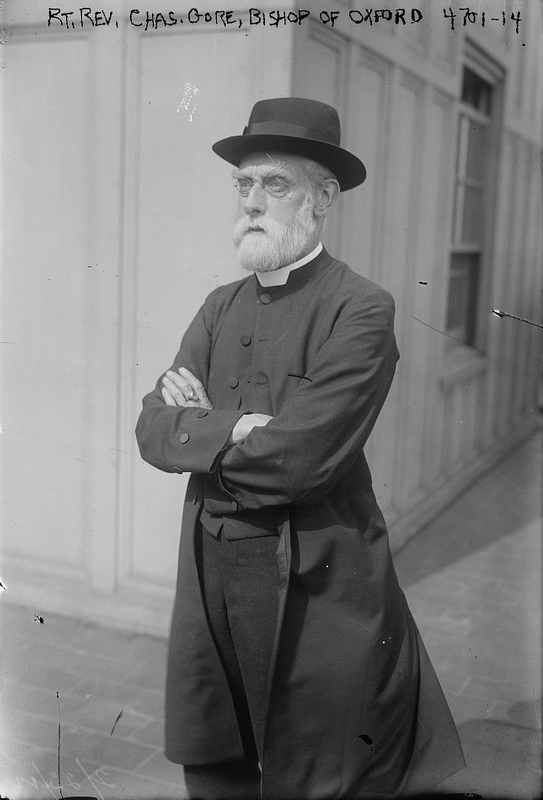

Editor’s note: The following sermon was delivered Sunday, November 25, 1883, by the Rev. Charles Gore, Trinity College, Principal of The Pusey House, Oxford.

‘The faith . . . once for all delivered.’— St. Jude 3.

The claim of Christianity to be a catholic or universal religion admits of a great variety of applications. It has, indeed, an application to the individual life, where it vindicates its power to interpret and redeem its every faculty and every stage of growth. But, confining ourselves now to the application of this claim to mankind in general, we find that it is threefold : —

The Christian faith claims catholicity as regards classes of society : ‘ there is neither bond nor free, neither male nor female.’

It claims catholicity as regards the nations of the earth: ‘there is neither Greek nor Jew, circumcision nor uncircumcision, barbarian nor Scythian.’

Finally, it claims catholicity as regards the ages of the world: it proclaims a Christ ‘the same yesterday, to-day, and for ever,’ a ‘faith once for all delivered’; and of a progress which would abandon this once given creed, it says through St. John’s lips, ‘He that goeth forward, and abideth not in the doctrine of Christ, hath not God: he that abideth in the doctrine, the same hath both the Father and the Son’ (2 John 9).

It was necessarily by the two first aspects of its claim that the Christian Church challenged observation in the early ages. The pagan world, Oriental Hellenic and Roman, was thoroughly familiarized with the idea of a superstitious religion of the vulgar, necessarily a thing apart from the philosophy of the educated; nor does it seem that the remarkable revival of pagan supernaturalism, which accompanied the spread of Christianity, had done anything material towards breaking down this division of society into two worlds of superstition and enlightenment. And thus indeed a new thing had been done in the earth when the Christian apologist can announce the first fulfilment, in a spiritual religion made popular, of the Church’s catholic claim: ‘our every Christian artisan has found God, and shows Him to you, and assigns to God, in fact, all that is desired in Him, though Plato declares that the maker of the universe can neither easily be found out, nor, when found out, spoken of to all men.’

It seemed no less ridiculous to the ancient world in general, in spite of the speculative ideas of a few later philosophers which remained wholly remote from realization, to aspire after a religion of all races. ‘Each state,’ the Roman said, ‘has its own religion, we have ours.’ Indeed it was the natural conclusion from experience that there could be no universal religion; and thus no less markedly than in the fellowship of classes in the Christian brotherhood, was evidence given of a new spiritual force working in the world by that fellowship of races in the unity of the faith, of which the Christians, even in early years, were able to boast so large a realization.

Christianity within her first three centuries went far to vindicate the first two aspects of her catholicity. Below distinctions of class and race she claimed to find and, in fact, stirred into consciousness the ‘general heart’ of humankind, in which humanity is one — common in its sympathies, common in its wants, in its sense of sin, in its capacity for fellowship with God; and in this region she found it true that there is neither male nor female, Jew nor Greek, barbarian nor Scythian, bond nor free.

We are familiar with the idea of a religion uniting classes and uniting races; so familiar that it is at times an effort to us to realize how contrary to the expectations of common sense the pretensions of Christianity seemed when they were first heard. Not but what we need to take care that we preserve in this respect the treasure we have been given. Christianity has been able to be (so far as she has yet realized her ideal) universal, because she has been content to be embodied in a visible society, to appeal to simple historical facts, to have a clear doctrine to teach, and to use material means, appealing to the eye and ear of all, to symbolize and mediate the spiritual realities. And we may depend upon it, that the temper of Gnosticism, in the nineteenth century as much as the second, which would substitute idea for fact, or forget that it is of the essence of Christianity ‘to assert the harmony of the flesh and of the spirit,’ will always end in restoring the old division between the religions of the superstitious and the cultivated; or, worse still, in robbing the uneducated of their religion altogether. Nor can it be said that we in England have never needed the warning that we must miss the richness of our Christian heritage if we go too far in nationalizing religion. We believe in a catholic Church.

But, on the whole, it is not so much these aspects of the catholic claim of Christianity which challenge criticism to-day, as that in virtue of which she claims the heritage of all the ages. Of course, a real believer in Christianity cannot be doubtful about the finality of his religion. A real belief at any moment in Christ as the incarnate Son of God, crucified and risen, involves us in a belief in the perpetuity of our creed; its perpetuity is involved in the conception of what it is. ‘The Word made flesh’ must be a final revelation.

But while a person yet falls short of a personal faith in Christ, such as secures that ‘he shall not be afraid of any evil tidings, for his heart standeth fast and believeth in the Lord,’ while the ‘smoking flax’ of a struggling faith still needs stirring into the clear flame, it is very possible, judging from external signs, for a person to be visited with a shrinking dread lest Christianity should be ‘decaying and waxing old,’ and be ‘ready to vanish away.’ It was a stupid infidelity, such a person will be disposed to say, which denied its enormous merits in the past; but the greatest things in the world may do their work and wear out, may ‘have their day and cease to be’; and may not Christianity, at least in the objective embodied form in which you speak of it, be one of these things? We do not say it is disproved, but is it not shaken? Have not science and criticism a little discredited its old assertions? Is it not somewhat timorous and apologetic, and may not another fifty years of freethinking be too much for its hold on reasonable minds as an exclusive and supernatural revelation?

There are, no doubt, many persons not disposed to unbelief who yet need reassurance on this matter of the permanence of Christianity, who need to be reassured that it is reasonable to believe in an unchanging revelation in a changing world; in a world too where we no longer reckon change as a mark of weakness, but of which we have come to feel it true that, within humanity and without, the very law and condition of life is change by development, evolution of one form of things out of another. How is it that in the middle of a changing world we can believe in an unchanging creed ?

Let us, then, with God’s blessing, endeavour as far as we may in the compass of what remains of a single sermon, to reassure ourselves that prima facie we need not fear to be doing anything unreasonable in putting our faith in the permanence of the Christian creed.

But we must first guard ourselves by explaining with what necessary limitations we claim this permanence. If we are wise, then, we shall surely not involve our faith in the permanence of the Christian system in a denial or a minimizing of the reality or depth of the political and intellectual changes that we are going through, or try to satisfy ourselves that the now prevalent unsettlement of intellectual convictions is a mere arbitrary fit of unbelief. No, we are indeed going through an epoch of very searching and radical change in politics and thought, and in any such epoch we must anticipate that to a certain extent the current Christian teaching, the actual Christian Church, will ‘suffer loss.’

Indeed, for a religion not to be deeply moved by current changes in political and intellectual life would imply that it stood in no close and vital connexion with these departments of human interest.

There is then a deep political change going on around us, and if our Christianity has largely linked itself to ‘an old order which changeth, yielding place to new,’ the readjustment of relations of Christianity to society must involve considerable uneasiness and great searchings of heart, and difficult reassertions of forgotten first principles. And we are living through an intellectual change, how deep, how all-pervading, we are bound to recognize. The broad idea of evolution has arisen and occupied, like an all-penetrating atmosphere, the minds of men, accompanied with an infinitely higher and subtler criticism than has been known before: and this broad conception of evolution finding exemplification in every department of nature, coupled with this new and vigorous criticism for its handmaid, has produced an intellectual advance, the magnitude of which it is very difficult to estimate, but the reality and importance of which it is impossible to doubt in the spheres, especially of science, literary criticism, and history.

Well, then, this intellectual advance could not (we must recognize) have failed to produce a disturbing effect upon, if not the body, then the clothing, of a revelation which claims to interpret nature in its relation to God, and to be chronicled in a literature, and to be related in history. Christianity (all Christians would surely admit in principle) has to interpret nature in relation to God in every stage of natural knowledge, but is not intended in any way to anticipate the result of natural investigation. This being so, we shall not be surprised to find that in epochs where science has been more or less stationary, there has been an inevitable tendency over-closely to identify the knowledge which is based on investigation, and is transitional, with the spiritual interpretation which is communicated and permanent, and the severance of the two and the readjustment of the interpretation to the new knowledge of the processes of nature must have produced some measure of confusion and disintegration.

Or, to take one other example of the kind of effect which a great intellectual transition inevitably produces on Christian doctrine, we have only to consider how Revelation, in its gradual development through the imperfect stages of the Old Testament, is mediated in a history and in a historical literature. The historical literature is inspired, but, if it remains a historical literature, it must be affected by any new laws which are found to govern universally the development of literature. If, for example, it became a known law in the evolution of literature that antecedently to the stage when it is either history or poetry or philosophy, there is a stage when it is neither, or all in the germ, ‘a stage of literature,’ to quote the words of Mr. Grote, in reference to the history of Greece, ‘which is the common root of all the different ramifications into which the mental activity of the race subsequently diverge; containing, as it were, the preface and germ of the positive history, philosophy, theology,’ and poetry ‘which we afterwards trace each in its separate development’ — if there be such a stage, from which (whatever we call it) we must, as Mr. Grote remarks, entirely dissociate all idea of ‘ fraud,’ this new conception of literature as a whole must affect our conception of Jewish literature, which is inspired; and we who have recognized that history and poetry and philosophy are capable of inspiration in different ways, shall not be long in seeing that there is no difficulty in conceiving the earlier stage to be inspired too. The change will not lie in the doctrine of inspiration, but in the conception of the historical literature which is to be inspired, and there need be no more ultimate danger of our confusing the one stage with the other in the Bible than of our confusing the two stages in the literature of Greece. But the process by which we adapt the new conception of historical evolution to the old doctrine of inspiration must be attended with some mental disturbance, and, in contemplating this certainty, what must reassure us is surely the broad fact that Christianity has passed through such changes before, and passed through them in substance intact. For it is a great comfort to observe that there has been in the received Christianity of every age an element not destined to be perpetual, just in that margin where the Revelation which is unchanging links on to the environment which is changing. Part of this latter is taken up and confused with what has adopted it. And so we remark that in transitional epochs Christianity is found to have lost something of what was commonly believed to be of the faith.

Now if this meant that the deposit of the Christian faith has had something taken from it by each intellectual advance, so that the creed believed by Christians who can think has become smaller and smaller in each successive age, that would be just what her enemies would want — but it does not mean this. There is a Christian creed in God Triune, in Christ, the Son of God Incarnate, in the Spirit perpetuating His presence in a visible society, in the order of a ministry and the significance of sacraments, in probation here and in judgement to come; and this creed is as a historic fact what has been held ubique, semper, ab omnibus in Christendom, if that maxim be interpreted with the limitation which common sense suggests. There is a historic creed in a historic Church, and it has been permanent, and the successive ages of change have not diminished that deposit, though they have generally shown the Church that over and above her creed she was teaching something which was not her own.

But the falling away of what was an alien accretion, or a mistaken explanation, from the body of Christian truth has not invalidated its legitimate fabric. It surely confirms our belief in the essential coherence of a body of truth to find that it can harbour and then throw off misconceptions without ultimate harm.

For example, there was a theory about the atonement, held almost universally in ancient times, with more or less emphasis, which represents Christ’s death as a ransom paid for our redemption to the tyrant who held us bound — Satan. The price of our redemption was paid to Satan. When Abelard repudiated this traditional view, St. Bernard in no measured language condemned him as guilty of an audacious impiety. In process of time this attempted explanation of a truth (for it was no more) fell away, and has been forgotten except as a matter of archaeology. But the rejection of the misconception of the atonement, however ingrained by long custom in the Church’s system, did not invalidate the tenure upon men’s minds of the truth.

Is not this fact suggestive? Does it not teach us that misconceptions may gather round an element of the Christian creed, that they may be rudely assailed, and defended with an unwise persistency by even the greatest teachers, and finally fall away without any disastrous effect to the faith of the Church?

We then shall not be surprised if we find an age of intellectual change, like the present, involving on the part of the Christian teacher a change of front in the outer territory of Christian teaching, as if that gave us any reason to fear that the body of Christian truth were wanting in permanence.

So then it remains for us to ask what are our primary, positive reasons — such as spring from the broad facts which meet us on the forefront of history and human nature — for believing in the permanence of our Christian creed?

1. First, surely, we may gather reassurance from the past history of Christianity. Not only has her power so largely shown to realize the first two aspects of her catholicity to which allusion was made — to find a human nature to appeal to which is one and the same beneath all distinctions of race and class — not only has her power already shown here given real earnest of her power to realize the rest of her promise, but, besides this, as a matter of fact, she has already in the past shown a marvellous power so to get down to the permanent roots of human life, as to pass in substance unchanged through the greatest possible crises and most radical epochs of change in human history.

It is not indeed the success of Christianity in any particular age which ought so much to excite our astonishment as her persistence — her persistence in spite of weakness which has more than once or twice seemed almost greater than to admit of recovery. The Christian Church spread at the first under remarkable conditions in the Roman Empire. As we look back we can see how much there was then in the temper and conditions of society which favoured her success. The unity of the empire — the facilities afforded by the prevalence of one or two languages over all the civilized world — the general tendency to organize associations and guilds — the revival of supernaturalist beliefs which belongs to the second and third centuries — the religious tone of the later Greek philosophy — these are among the many elements in society which favoured her spread. But in the West at least all these elements of social organization collapsed. Exactly in proportion as we prove that Christianity had every reason for spreading in the first three centuries do we increase the surprise we ought to feel at her power manifested to subsist through the stupendous series of social convulsions and upheavals which link the modern to the ancient world. In proportion as she was suited to the old, she would have been unsuited to the new. Exactly as much as we reduce the impression made on us by the diffusion of Christianity, we increase the impression made by her continuity. That she alone of all Roman organizations passed unchanged through the great transition, indicates that she alone had a basis in human life which reached down below what is transitory and belongs to one state of society, into that underlying humanity which makes all ages one.

2. Again, Christianity, which has passed unscathed in substance through a great number of these transitions, and like God’s good steward again and again has ‘brought forth out of her treasury things new and old,’ is passing now through another conflict. Should we not find reassurance in the fact that the panics with which the faith of our own generation has been assailed are storms which the ship of Christian faith is already showing signs that she can weather. For example, it cannot be denied that the horror with which, not wisely perhaps, but certainly not unnaturally, new conceptions of evolution in nature were at first regarded by theologians and Christian teachers is passing away, and they at least are declaring on all sides and in all good faith that they do not find their frankest acceptance at all inconsistent with a Christian belief: or to take another example; if we look back and recall the panic which followed the publication of the book called Supernatural Religion, and the tone in which the press spoke of the result of that book, must we not admit that anticipations adverse to the power of Christianity to substantiate the claims of its Gospels as historical documents have not been realized, and that any one who has followed the controversy with care will come to see that the Gospels now are in a much stronger evidential position than they were before?

3. Again, if we are tempted to take an over-ideal view of development as the law of the world, and to fear that Christianity by the very fact that it claims finality proves its falsity, is there anything more reassuring than to consider carefully the broad fact that Christian morality has, as a matter of history, vindicated its claim in this respect. A morality — an ideal of human life, individual and social — promulgated in Syria 1800 years ago, proclaimed in its completeness by a few, mostly not highly educated men, of Jewish birth and training, within the limit of a few years — this ideal has remained through the ages, and almost nobody seriously claims to find it deficient. A Christian student reads, shall we say, St. Augustine. He finds there an illustration drawn from a superseded natural science: he is quite ready to laugh at it: he finds the Bible interpreted by a criticism which he cannot but regard as imperfect, and he does not scruple to demand a better: but he finds a wealth of moral and spiritual truth, a depth of spiritual insight, a knowledge of the human soul, a power of applying to it the remedies of Christian truth, which cannot be superseded. The master of spiritual lore in the fourth century is a master still. What does this broad difference between spheres of human knowledge mean? It means that while science and criticism have developed, moral and spiritual truth have, in the same sense, not. That Christian morality, with its perfect synthesis of complete self-sacrifice with complete self-realization, of individuality with fellowship, of fear with love, of faith with wisdom — almost nobody in moral seriousness claims to criticize it. At any rate those who do appeal very little to our consciences and better reason. But, then, what a vast admission is here. It means that morality has, under circumstances when such a fact was not at all to be expected, vindicated its finality; each successive generation has but to go back and drink its fill afresh from that unexhaustible source of a moral ideal which is catholic.

4. And if we are convinced of this, if we are convinced that in this moral and spiritual sphere of human life an ideal promulgated 1800 years ago in an eastern country has shown every sign of being universal and final, if we are convinced that the law of evolution has here something which in actual experience limits its application, then it seems no great step to ask a person to admit that this finality shall be attributed, not to the life merely in ideal and effect, but to what St. Paul calls the ‘mould’ of Christian teaching which fashions the life. For just as surely as in the lapse of years we identify the Mahommedan character with the Mahommedan creed, and in the creed recognize the condition of the character, just so surely we must recognize the whole organism of the historic Christian system as the condition of the Christian morality. Any view of human life over a long reach (and we must always recognize that it is only in the long reaches of human life that its logical aspect emerges: human nature taken in a latitudinal section is a mass of inconsistencies, and men are constantly seen clinging to the results of abandoned convictions; but it is unfailingly logical in the long run) — any view then of human life over a long reach identifies Christian morality with Christian motives, and Christian motives run up at once to supernatural facts, to the personal immortality of the soul, to the love of a personal God, to the Incarnation of the Son of God. Study a really Christian life, the life of any one whom from a moral and spiritual point of view you would number among the truly great, the saints of history: how indissolubly linked are the actual virtues of such a man to motives which involve the supernatural world and the Christian creed. Is there any consideration in the world which can call itself scientific which would justify us in supposing that a life consciously and confessedly moulded by a body of truths can go on existing without those truths? Is it not contradicting all principles of science to imagine that a changed environment of truth will not produce a changed product? The prayerful temper must excite our admiration, but is it not inconceivable that the prayerful temper can be developed except on the basis of a belief in a personal God to whom we can have personal and open access? The temper of penitence we know to be one of the most absolute essentials of spiritual progress. But the temper of penitence is the simple product of a belief at once in the personal holiness and personal love of God, a belief which can become conviction only in the revelation of Christ.

Yes! depend upon it, there is no reason why Christian morality should be capable of being permanent, except because the spiritual and moral faculties and wants of man are permanent: and these permanent wants and faculties of man it is Christianity — that is, the body of Christian truth revealed in Christ — which alone has had in historical experience the power to evoke into consciousness, to satisfy, to develop, to actualize into the living beauty of a Christian life at peace with self, with God, with man.

Well then, to conclude, it would seem that we may ask a person who is impressed with these reassuring aspects of Christian history — with this permanence of Christian morality in indissoluble fellowship with Christian truth — to take up an attitude somewhat of this kind toward the world of intellect and spirit. He will regard himself as belonging to humanity, not in one department of human activity only. In that department of human life which is gradually enriched by inquiry and research he will no doubt be zealous to accept every development of legitimate knowledge, as each in its turn secures its position. He will not fail to recognize as his own the achievement of humanity in its intellectual progress in science, history, and criticism. So he will be the child of his age. But he will recognize in himself a fellowship — may I not say a prior and a deeper fellowship? — with humanity in that other area in which she must recognize a closer and a more unchanging fellowship with past ages; aye, an abiding dependence upon a voice once spoken, an ideal once given, a life once lived. He has a conscience, a faculty of prayer, a capacity of communion with God, a sense of sin, a need of spiritual light, a desire of inward peace, and in that he has these, he is one with the humanity of all ages in that respect in which Christianity alone has really claimed, and made good its claim, to interpret, to foster, to develop, to secure man’s nature. Thus he will see two worlds opening before him, the world of developing knowledge, and the world of spiritual life and spiritual truth; and in those deepest, silentest strongholds of man’s spiritual being, in which we swear the great oaths which mould and fashion our life, he will pledge himself, as on the one hand to fear no light of intellect and love the darkness nowhere, so on the other to be utterly true to the light of his spiritual being. And if he recognizes the authority of intellectual humanity in the one sphere, he will recognize the authority of spiritual humanity in the other. But there is something prior to authority: it is the consciousness of self; it is the obligation to be true to oneself. If in times past men have claimed of theological authority that it must not contradict or override a man’s own conscience, we need now to make the same claim in the interest of religion. A man has got a right to ask authority from a humanity larger than his own narrow life, to explain to him what falls outside his own experience — to anticipate and then to interpret his own experience ; but no authority, ecclesiastical or scientific, can override our own consciousness. My own conscience, my own capacity for prayer, my own need of God, this is the inalienable witness of God within me, and I abrogate the prerogative of personal life, and the obligation of personal responsibility, if I allow an authority outside myself to explain away my own consciousness. Whether the testimony of conscience involves a divine claim on my life: whether it has not the absolute supremacy in the hierarchy of my faculties: whether I have not a capacity for prayer, which involves a capacity for communion with God, which nothing but a knowledge of God can satisfy: whether I do not need the constant thought of judgement, aye, of an eternal judgement, to stir my sluggish spiritual energies, to enlarge my horizon of vision and make it seem worth while to carry on the fundamental, subtle, ceaseless struggle against sin within — these are questions which I must solve for myself. I have got no more business to go to the scientific world to explain away in this respect the verdict of my own consciousness, than I have got to get a board of theologians to explain away the conclusions of science. In this spiritual department of my life, then, I will cultivate my fellowship with humanity at its best, and its most unchanging. I will cultivate that department of my life in which rich and poor, Englishman and African, the nineteenth century and the first, can meet and be one. I will enroll myself in that great movement of a redeemed humanity, which in every age has confessed its sin, and purified its motives by self-discipline, and rejoiced in the friendship of God — that great movement which in every age has had within itself the same consciousness of spiritual triumph, and utters the secret of its triumph in the same unchanging words, ‘This is the victory that overcometh the world, even our faith! Who is he that overcometh the world but he that believeth that Jesus is the Son of God!’ I will dare to believe that if I will develop my spirituality by those instruments which the experience of ages has proved and not found wanting, and my intellectual capacities by the best modern lights, I shall not find that they will arrive at any dualism. I shall not find that my intellect need make me afraid of my soul or my spirit. I shall not find that I need be the less an Englishman of my own age, because I will have an entire and unbroken fellowship with nineteen centuries of Christian experience. What can one man do for another in such a matter except speak what he has heard, and testify what he hath seen? One man may speak to another, and say that he has tried to believe in intellectual progress and the unchanging Church and Creed, and he has never found them come into anything else than final harmony.

So it may be: so please God it will be with us. So shall we realize ever more and more how much of human life there is that is permanent and unchanging, and we shall contemplate the permanence of the Creed of Christendom, because we know that ‘deep in the general heart’ of human kind — that human kind which all the world over suffers and endures, and sins and knows it has sinned, and cries out for God —

‘Deep in the general heart of man’

Its ‘power survives.’