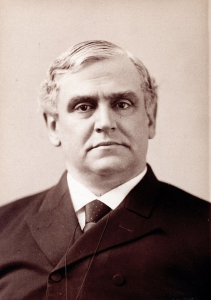

Editor’s note: The following is extracted from The Candle of the Lord, and Other Sermons, by Rev. Phillips Brooks (published 1881).

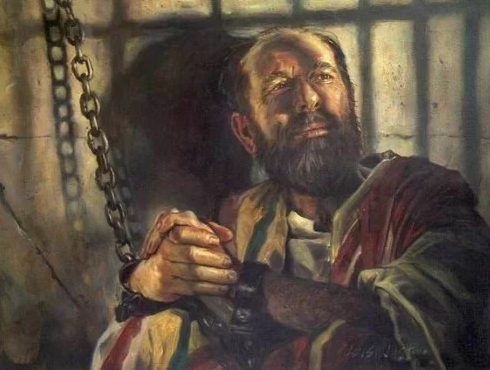

“From henceforth let no man trouble me, for I bear in my body the marks of the Lord Jesus.”

— Galatians vi. 17.

A man who is growing old claims for himself in these words the freedom and responsibility of his own life. He asks that he may work out his own career uninterfered with by the criticism of his brethren. He bids them stand aside and leave him to the Master whom he serves and by whom he must be judged. How natural that demand is! How we all long at times to make it! How every man, even if he dares not claim it now, looks forward to some time when it must be made. He knows the time will come when, educated perhaps for that moment by what his brethren’s criticism has done for him, he will be ready and it will be his duty to turn aside and leave that criticism unlistened to and say, “From henceforth let no man trouble me. Now I must live my own life. I understand it best. You must stand aside and let me go the way where God is leading me.” When a man is heard saying that, his fellow-men look at him and they can see how he is saying it. They know the difference between a wilful and selfish independence, and a sober, earnest sense of responsibility. They can tell when the man really has a right to claim his life; and if he has, they will give it to him. They will stand aside and not dare to interfere while he works it out with God.

This was St. Paul’s claim, and he told the Galatians what right he had to make it. “From henceforth let no man trouble me, for I bear in my body the marks of the Lord Jesus.” It is the reason for his claim of independence that I want to study with you. “I bear in my body the marks of the Lord Jesus.” He was growing an old man. Anybody who looked at him saw his body covered with the signs of pain and care. The haggard, wrinkled face, the bent figure, the trembling hands; the scars which he had worn since the day when they beat him at Philippi, since the day when they stoned him at Lystra, since the day when he was shipwrecked at Melita; all these had robbed him forever of the fresh, bright beauty which he had had once when he sat, a boy, at the feet of old Gamaliel. He was stamped and marked by life. The wounds of his conflicts, the furrows of his years, were on him. And all these wounds and furrows had come to him since the great change of his life. They were closely bound up with the service of his Master to whom he had given himself at Damascus. Every scar must have still quivered with the earnestness of the words of Christian loyalty which brought the blow that made it. See what he calls these scars, then. “I bear in my body the marks of the Lord Jesus.” He had a figure in his mind. He was thinking of the way in which a master branded his slaves. Burnt into their very flesh, they carried the initial of their master’s name, or some other sign that they belonged to him, that they were not their own. That mark on the slave’s body forbade any other but his own master to touch him or compel his labor. It was the sign at once of his servitude to one master and of his freedom from all others. So St. Paul says that these marks in his flesh, which signify his servantship to Jesus, are the witnesses of his freedom from every other service. Since he is responsible to his Master he is responsible to no one else. “From henceforth let no man trouble me, for I bear in my body the marks of the Lord Jesus.”

It is a vivid, graphic figure. I hope that we shall find that it may be as true of the life of any one of us as it was of the life of Paul. We see at once with what a pathos and a dignity it clothes the human body. It makes the body the interpreter of the spiritual life that goes on within it, the register of its experiences. A very clumsy and imperfect interpreter of the soul indeed the body is, and yet we all know that it gets its real interest from what power of interpretation and record it does possess. A scar upon the face recalls some time of pain and peril, and lets us know of a soul that has undergone the discipline of danger. Whether the pain came and was met nobly or meanly, whether it was the peril of the soldier or the peril of the burglar, the dumb scar cannot tell. The quiet peaceful smile upon the face declares the soul at rest; but whether the rest be idle self-indulgence, or the satisfaction of a soul at peace with duty, only he who reads behind the smile into its subtlest meaning is able to discover. Yet in its clumsy, halting way the outer is the record of the inner life. The body tells the story of the soul. We bear in our flesh the marks of our masters. The hard hand of the laborer tells that he is the servant of unpitying toil. The knit brow of the merchant declares what master sits over him in his anxious office. The serious forehead of the thinker reveals his service to his master, Truth. And when we lay a human body in the ground at last there is a reverence or a pity which starts within us as we see the coffin lid close on the marks of noble or ignoble servantship which years have left written on the face.

This is the principle on which rests St. Paul’s description of himself. And now let us see how that same description may be true of men today; how they still may bear in their bodies the marks of the Lord Jesus, the very brands, as it were, which declare them to be His servants, His property. Here is a man whose body shows the signs of toil and care. I will not read the long familiar catalogue. The whitened hair, the cautious step, the dullness in the eye, the forehead seamed with thought; you know them all, you watch their coming in your friend, you feel their coming in yourself. What do they mean? In the first and largest way they mean life. The difference between this man and the baby, in whose soft flesh there are no branded marks like these, is that this man has lived. But then they mean also all that life has meant; and life, below its special circumstances, always means the mastery in obedience to which all the actions have been done and all the character has taken shape. “Who is your master?” is the question that includes all questions. And if a man tries to push that question aside; if he says, “Nay, but my life cannot be judged so, for I have no master,” still he answers the question which he rejects. He answers it in rejecting it. He declares that he is his own master. And then he bears in his body the marks of himself; the faded colors and the scars mean only wilfulness and selfishness. But now suppose that life has meant for that man, from the beginning, the claiming of his soul by a higher soul; suppose that every new experience has seemed in its heart, its meaning, its spirit, to be only a little closer overfolding and embracing of the will by the Supreme Will; suppose that as the result of all, as the blended and completed issue of all this living, the life is Christ’s life, uttering His wishes, seeking His purposes, filled and inspired by His love, reckoning its vitality by the degree of conscious and realized sympathy with Him; suppose all this, and then it will be true that every outward sign in which those inward experiences are recorded will become a mark of the Lord Jesus, a sign of that occupation of the nature by His nature, of the ownership of the man by Him, which is what it has meant for this man to live.

For instance, here among the white careworn features there are certain lines which tell, beyond all misunderstanding, that this man has struggled and has had to yield. Somewhere or other, sometime or other, he has tried to do something which he very much wanted to do, and failed. As clear as the scratches on the rock which make us sure that the glacier has ground its way along its face, so clearly this man lets us know that he has been pressed and crushed and broken by a weight which was too strong for him. What was that weight? If it were only disappointment, then these marks are the marks of simple failure. If the weight were laid on him as punishment, then these marks are marks of sin. If it were a weight of culture, then the marks are marks of education. If the weight was the personal hand of the Lord Jesus Christ teaching the man that his own will must be surrendered to the will of a Lord to whom he belonged; if the Lord Jesus Christ has been drawing him away from every other obedience to His obedience; then these marks which he bears in his body are the marks of the Lord Jesus. It is as if a master, seeking for his sheep, found him all snarled and tangled in a thicket, clinging to and clung to by the thorns and cruel branches. He unsnarls him with all tenderness, but the poor captive cannot escape without wounds. He even clings himself to the thorns that hold him, and so is wounded all the more. When the rescue is complete and the master stands with his sheep in safety, he looks down on him and says : “I need not brand you more. These wounds which have come in your rescue will be forever signs that you belong to me. No other sheep will carry scars just like them, for every sheep’s wanderings, and so every sheep’s wounds, are different from every other’s. Their pain will pass away, but the tokens of the trials through which I brought you to my service will remain. They shall declare that you are mine. You shall bear in your body my marks forever.”

And then what follows? Freedom! “I bear in my body the marks of the Lord Jesus; therefore let no man trouble me.” I think that we have all seen how there are two classes among experienced and world-worn men. Some men with their scars and wrinkles and wounds grow timid, cringing, and spiritless. Their only object seems to be to get through the rest of life with as few more shocks and blows as possible. They apologize for living. They try to keep out of other men’s way and so are always open to their criticism, and slaves of their whims. Poor broken creatures they are. And then there are other men, whose hard experience of life has evidently lifted them away from any anxious care about what other men may think of them, given them an independent self-contained life, and made them free. What is it that makes the difference? Does it not all depend on this: on whether the experience of life has given a man any new master whom he trusts and serves; on whether the “marks in his body,” the scars and bruises, are the ownership marks of any recognized and trusted Lord; or whether they are only the unmeaning records of an aimless drifting hither and thither among the rocks? The master may be more or less worthy. If there only be a master, the man is free from all other servitudes. His marks are signs of liberty. It may be only that he has made his own passions his lord. In self-indulgence and self-admiration he may have settled down to the mere service of himself. But even in selfishness there is freedom. The man of fixed contented selfishness is liberated from a hundred cares about what other people think of him, or what they have a right to ask. But let the new master which life has given us be a principle, a cause, even a petty conscientious scruple, and then how clear the freedom from our fellows’ tyranny becomes. “From henceforth let no man trouble me, for I must do my duty; I must work out my study; I must maintain my cause.” Very hard and sullen and cruel often grows the independence that is born of such a mastery. But now suppose that not one’s self, and not some abstract cause, but the Lord Jesus is the Master to whom the body’s marks bear witness. The strongest and yet the gentlest of all masters! The gentlest yet the strongest! Then comes an independence which is complete and yet which has no bitterness. There is no crude and weak contempt of fellow-men, while yet there is a calm and complete assertion that no fellow-man must hinder or intrude upon our life.

Indeed there is, in all the independence which the Christian as the servant of Christ claims with reference to his fellow-men, this subtle element which always redeems his independence from indifference or cruelty, — that the first duty which his new Master lays upon him is to go and serve and help those very fellow-men from whom he has plucked away his life, that he may give it completely to this loftier service. This is the noble poise and balance of the Christian life. Christ rescues the soul from the obedience of the world in order that in His obedience it may serve the world with a completer consecration. The soul tears itself away from slavery to the world and gives itself to Christ; and lo, in Him it serves the world for which He lived and died, with a devoted faithfulness of which it never dreamed before. Paul was never so busy working for men as in this very day when he cried out, “Let no man trouble me.” His cry was primarily a demand that no man should dare to question his apostolical commission, because Christ had adopted him; but the more earnestly that he refused to let men question that deep transaction which lay between his soul and his Master’s, so much the more completely did he give himself up to the service of the men who he insisted should not be his judges or his lords.

One principle you see lies at the bottom of all that we are saying, of all that Paul says in this verse. It is that no man in this world attains to freedom from any slavery except by entrance into some higher servitude. There is no such thing as an entirely free man conceivable. If there were one such being he would be lost in this great universe, all strung through as it is with obligations, somewhere in the net of which every man must find his place. It is not whether you are free or a servant, but whose servant you are, that is the question. This was what Jesus said. “No man can serve two masters.” “Ye cannot serve God and mammon.” It was always a choice of masters to which He was urging men. The Son who was to “make them free so that they should be free indeed,” was to be one to whom they should show their love by “keeping His commandments.” To know this truth is the first opening of the gates of life to a young man. It is not by striking off all allegiance, but by finding your true Lord and serving Him with a complete submission, that you can escape from slavery. “I will walk at liberty, for I keep Thy commandments,” said David. This is the universal necessity of faith, which is but the obedience of the complete man, soul as well as body. This is the everlasting and fundamental difference between two inquiring and seeking souls. One of them is looking for some door which shall lead out into absolute freedom. The other is asking with free-eyed earnestness for its true Master. Before the one there can be nothing but vague restlessness and endless discontent. The other shall certainly some day arrive at peace in believing and obeying. O my dear friend, look for your master. Be satisfied with none until you find Him who by His love and His wisdom and His power has the right to rule you. Then give yourself to Him completely. Let Him mark you as His by whatever marks He will. Count every such mark a privilege. Find in His service the charter of your freedom. Resist all other men’s intrusion on your life, because your life belongs to Him. Be jealous for it as your Lord’s domain. That is the real emancipation of the soul of a child of God, its total consecration to its Father.

It is not only in the duties of active life that a man receives the mark of Christ and enters into the liberty which He bestows. The same liberation sometimes comes by sickness and the incapacity for work. I can speak perhaps more clearly if I picture to myself someone here in my congregation on whom that calamity has fallen. For years you have been doing your part in the world. You have held your own. You have asked nothing, you have taken nothing, from your fellow-men. But suddenly, it may be, the blow has fallen on you. Sickness has come. You cannot work. You are dependent where you used to trust only in yourself. How terrible it is! How it seems as if now all liberty were gone. You must stretch out your hand in your blindness for somebody to lead you. You must open your helpless mouth for somebody to feed you. Life seems all slavery and uselessness. What can release you? If it could come to pass that by your pain you should be brought into a personal knowledge of Him who can console your pain; that by your weakness you could be brought to a personal reliance on His strength; and so your pain and weakness could become to you profoundly and inseparably associated with your allegiance to Him, — then see! Would they not be transformed? Still you must rest on others for what you would gladly do for yourself. But it would be no enfeeblement, no demoralization of your life. The higher meaning of your pain would swallow up its lower meaning. The association which it made for you with God would overrule the association which it made for you with your brethren. Through Him on whom it made you able to rely, you would be strengthened so that even those on whom you rested physically every day would feel your strength and spiritually rest on you. That would be freedom for you.

Such sicknesses there are. Such we have sometimes known; some men or women, helpless so that their lives seemed to be all dependent, who yet, through their sickness, had so mounted to a higher life and so identified themselves with Christ that those on whom they rested found the Christ in them and rested upon it. Their sick rooms became churches. Their weak voices spoke gospels. The hands they seemed to clasp were really clasping theirs. They were depended on while they seemed to be most dependent. And when they died, when the faint flicker of their life went out, strong men whose light seemed radiant, found themselves walking in the darkness; and stout hearts on which theirs used to lean, trembled as if the staff and substance of their strength was gone. A noble freedom certainly is this in which the arm that holds you up is really held up by you; in which, while others think they are supporting you, you really are supporting them; and this noble freedom may come to any weak and wounded life whose wounds and weakness have become the signs and tokens that it belongs to Christ.

But I must not seem to speak as if it were only the sick and wounded in the great army of life upon whom the great Captain’s mark is set. There are too many young eager, hopeful lives here before me who belong in the very van of that army, and whose strength and health find no worthy and sufficient explanation, unless we see in them the marks by which the Lord of our humanity would claim the choicest of our humanity for his own. Remember what the Incarnation was. “The Word was made flesh and dwelt among us.” Then were the capacities of our human flesh declared. Then in the strong and healthy life of Jesus it was made known to what divine uses a strong body might be given. And since everything in this world properly belongs to the highest uses to which it may possibly be put, the strong human body was there declared to belong to righteousness and God. Thenceforward, after Jesus and His life, wherever human flesh appeared at its best, wherever a human body stood forth specially strong, specially perfect and beautiful, it had the mark and memory of the Incarnation on it. It might be totally perverted. It might be given to the Devil. But, since the work that Jesus did, the life that Jesus lived in a human body, the human body in its fullest vigor has belonged to the high work which He did in it, the service of God and help of fellow-man. Its vigor is His mark upon it. Feel this, and then how sacred becomes the body’s health and strength. It is no chance, no luxury. God means that in it you should do work for Him. By it He claims you for His own. He to whom God has given it, is bound to have strong convictions, a live conscience, and intense earnest purposes of work.

Let a young strong man feel this and then he claims the proper freedom of his youth. “Let no man trouble me,” he says, “for I bear in my body the marks of the Lord Jesus.” I have tried to show you what those words mean when an old man says them out of the heart of his experience, with the bruises and scars of a hard life all over him. Even more solemn and full of meaning they are when a young man says them in the conscious vigor and full consecration of his youth. “You must not hamper and restrain me,” he asserts. “You must not turn me from my way to yours. You must not coldly criticize all that I try to do. You must not ask me to conform to all the traditions which your cautiousness marks out. You must let me risk something of repute, of fortune, of comfort, of life itself, to do my duty. You must not think me arrogant or self-conceited if I disregard both your anxiety and your sneers, and go the way, the new way, the strange way, that is clearly set before me.” It is a noble thing when out of all the jealousy, out of all the anxiety and love of older men, a young man thus quietly and firmly claims his life; but the nobleness only comes when he claims his life because Christ has claimed him, and because the full vigor and health in which he glories are to him marks of the Lord Jesus. To give one’s life up timidly to the traditions that demand it on the one hand, and to assert one’s independence in pure wilfulness on the other; both of these are perversions of the purpose for which we were made. To insist that we must have our lives to ourselves, that their own power may be worked out freely because we belong to Christ, that is the perfect scheme of existence, the sanctification of liberty, the transfiguration of ambition.

It is not hard, I think, to believe that something of this sort of symbolic consecration, this consecration of the spirit under the body’s symbols, may pass over into the other life, and so may last forever. St. Paul tells us that in heaven we are to have a spiritual body in place of the natural body which we wear here. The privilege of that spiritual body must be to express with perfect clearness the experiences of the spirit which will then be the master. And if the great experience of the soul must always be redemption, redemption remembered in its beginning here, and ever going on to its completion through eternity, then certainly the body, which in some mysterious way will bear the record of that process, cannot fail to speak of Christ the Redeemer. The unimaginable perfectness which will belong to every organ will forever utter Him. Every perfection will be a new mark of the Lord Jesus. And since each saint’s belonging to the Savior must be forever different from every other’s, each saint will have in his spiritual body his own “marks of the Lord Jesus;” the signs of how his Lord has claimed him with a discriminating love that is entirely his own, different from that with which every other saint in all the millions has been saved.

In such a thought as that there opens before me all the social life of heaven. It is all liberty. No redeemed spirit shall ever have the power or the wish to encroach a hair’s breadth upon the development of the redeemed life in any other. Each shall grow free and straight towards its own perfectness. And yet between these free lives, which never invade one another, there will always be the complete sympathy of a common dependence upon the one Source and Savior of them all. They will be all one, because they all belong to Christ, and yet the separateness of each shall be kept perfect because each is claimed with its own peculiar claim and marked with its own special mark. In all the solemnity of personalness and all the sweetness of brotherhood, the celestial life shall flow along its ever deepening way.

And must we wait for that until we get to heaven? O my dear friends, in this world, full of crude self-assertion and of feeble conformity, in this society where men invade each other’s lives, and yet where, if one man stands out and claims his own life, his claim seems arrogant and harsh and makes a discord in the feeble music to which alone it seems as if the psalm of life could be sung; how sometimes we have dreamed of a better state of things in which each man’s independence should make the brotherhood of all men perfect; where the more earnestly each man claimed his own life for himself the more certainly other men should know that that life was given to them. Must we wait for such a society as that until we get to heaven? Surely not! Even here every man may claim his own life, not for himself but for his Lord. Belonging to that Lord, this life then must belong through Him to all His brethren. And so all that the man plucked out of their grasp, to give to Christ, comes back to them freely, sanctified and ennobled by passing through Him who is the Lord and Master of them all. For such a social life as that we have a right to pray.

But we may do more than pray for it. We may begin it in ourselves. Already we may give ourselves to Christ. We may own that we are His. We may see in all our bodily life, — in the strength and glory of our youth if we are young and strong, in the weariness and depression of our age or feebleness if we are old and feeble, — the marks of His ownership, the signs that we are His. We may wait for His coming to claim us, as the marked tree back in the woods waits till the ship builder who has struck his sign into it with his axe comes by and by to take it and make it part of the great ship that he is building. And while we wait we may make the world stronger by being our own, and sweeter by being our brethren’s; and both, because and only because we are really not our own nor theirs, but Christ’s. Such lives may He give to us all!

5