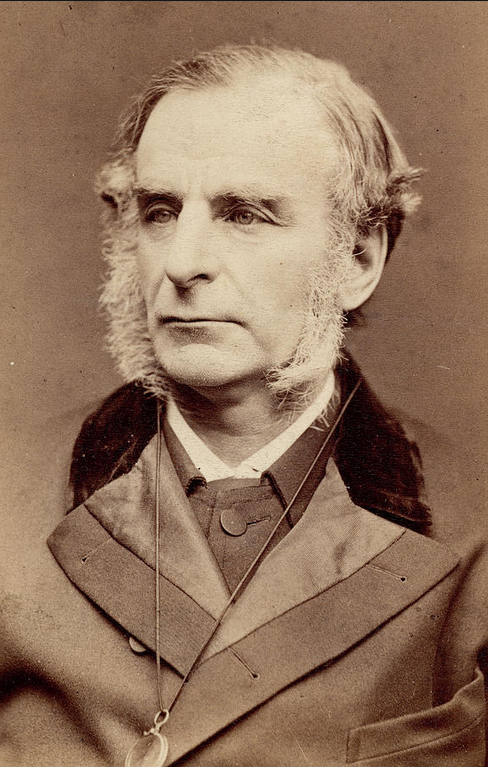

Editor’s note: The following is extracted from All Saints’ Day and Other Sermons, by Charles Kingsley (published 1878).

__________________________________________________

Westminster Abbey. November, 1874.

Malachi iii. 1, 2. “The Lord, whom ye seek, shall suddenly come to His temple…. But who may abide the day of His coming? and who shall stand when He appeareth? for He is like a refiner’s fire, and like fuller’s soap.”

We believe that this prophecy was fulfilled at the first coming of our Lord Jesus Christ. We believe that it will be fulfilled again, in that great day when He shall judge the quick and the dead. But it is of neither of these events I wish to speak to you just now. I wish to speak of an event which has not (as far as we know) happened; which will probably never happen; but which is still perfectly possible; and one, too, which it is good for us to face now and then, and ask ourselves, If this thing came to pass, what should I think, and what should I do?

I shall touch the question with all reverence and caution. I shall try to tread lightly, as one who is indeed on hallowed ground. For the question which I have dared to ask you and myself is none other than this—If the Lord suddenly came to this temple, or any other in this land; if He appeared among us, as He did in Judea eighteen hundred years ago, what should we think of Him? Should we recognise, or should we reject, our Saviour and our Lord? It is an awful thought, the more we look at it. But for that very reason it may be the more fit to be asked, once and for all.

Now, to put this question safely and honestly, we must keep within those words which I just said—as He appeared in Judea eighteen hundred years ago. We must limit our fancy to the historic Christ, to the sayings, doings, character which are handed down to us in the four Gospels; and ask ourselves nothing but—What should I think if such a personage were to meet me now? To imagine Him—as has been too often done—as doing deeds, speaking words, and even worse, entertaining motives, which are not written in the four Gospels, is as unfair morally, as it is illogical critically. It creates a phantom, a fictitious character, and calls that Christ. It makes each writer, each thinker—or rather dreamer—however shallow his heart and stupid his brain—and all our hearts are but too shallow, and all our brains too stupid—the measure of a personage so vast and so unique, that all Christendom for eighteen hundred years has seen in Him, and we of course hold seen truly, the Incarnate God. No; we must think of nothing save what is set down in Holy Writ.

And yet, alas! we cannot use in our days, that which eighteen hundred years ago was the most simple and obvious test of our Lord’s truthfulness, namely His miraculous powers. The folly and sin of man have robbed us of what is, as it were, one of the natural rights of reasoning, man. Lying prodigies and juggleries, forged and pretended miracles, even—oh, shame!—imitations of His most sacred wounds, have, up to our own time, made all rational men more and more afraid of aught which seems to savour of the miraculous; till most of us, I think, would have to ask forgiveness—as I myself should have to ask,—if, tantalized and insulted again and again by counterfeit miracles, we failed to recognise real miracles, and Him who performed them. Therefore, for good or evil, we should be driven back upon that test alone, which, after all, perhaps, is the most sure as well as the most convincing—the moral test—the test of character. What manner of personage would He be did He condescend to appear among us? Of that, thank God, the Gospels ought to leave us in no doubt. What acts He might condescend to perform, what words He might condescend to speak, it is not for such beings as we to guess. But how He would demean Himself we know; for Holy Writ has told us how He demeaned Himself in Judea eighteen hundred years ago; and He is the same yesterday, today, and for ever, and can be only like Himself. But should we know Him merely by His bearing and character? Should we see in Him an utterly ideal personage—The Son of Man, and therefore, ere we lost sight of Him once more, the Son of God? Let us think. First, therefore, we must believe that—as in Judea of old—Christ would meet men with all consideration and courtesy. He would not break the bruised reed, nor quench the smoking flax. He would not strive, nor cry, nor let His voice be heard in the streets. He would not cause any of God’s little ones to offend, to stumble. In plain words, He would not shock and repel them by any conduct of His. Therefore, as in Judea of old, He would be careful of, even indulgent to, the usages of society, as long as they were innocent. He would never outrage the code of manners, however imperfect, however conventional, which this or any other civilised nation may have agreed on, to express and keep up respect, self-restraint, delicacy, of man toward man, of man toward woman, of the young toward the old, of the living toward the dead. No.

As I said just now, He would never cause, by any act or word of His, one of God’s little ones to stumble and fall away.

I used just now that word manners. Let me beg your very serious attention to it. I use it, remember, in its true, its ancient—that is, in its moral and spiritual sense. I use it as the old Greeks, the old Romans, used their corresponding words; as our wise forefathers used it, when they said well, that “Manners maketh man;” that manners are at once the efficient cause of a man’s success, and the proof of his deserving to succeed: the outward and visible sign of whatsoever inward and spiritual grace, or disgrace, there may be in him. I mean by the word what our Lord meant when He reproved the pushing and vulgar arrogance of the Scribes and Pharisees, and laid down the golden rule of all good manners, “Whosoever will be great among you, let him be your minister; and whosoever will be chief among you, let him be your servant.”

Next, I beg you to remember that all, or almost all, good manners which we have among us—courtesies, refinements, self-restraint, and mutual respect—all which raises us, socially and morally, above our forefathers of fifteen hundred years ago—deep-hearted men, valiant and noble, but coarse, and arrogant, and quarrelsome—all that, or almost all, we owe to Christ, to the influence of His example, and to that Bible which testifies of Him. Yes, the Bible has been for Christendom, in the cottage as much as in the palace, the school of manners; and the saying that he who becomes a true Christian becomes a true gentleman, is no rhetorical boast, but a solid historic fact.

Now imagine Christ to reappear on earth, with that perfect outward beauty of character—with what Greeks and Romans, and our own ancestors, would have called those perfect manners—which, if we are to believe the Gospels, He shewed in Judea of old, which won then so many hearts, especially of the common people, sounder judges often of true nobility than many who fancy themselves their betters. Conceive—but which of us can conceive?—His perfect tenderness, patience, sympathy, graciousness, and grace, combined with perfect strength, stateliness, even awfulness, when awe was needed. Remember that, if, again, the Gospels are to be believed. He alone, of all personages of whom history tells us, solved in His own words and deeds the most difficult paradox of human character—to be at once utterly conscious, and yet utterly unconscious, of self; to combine with perfect self-sacrifice a perfect self-assertion. Whether or not His being able to do that proved Him to have been that which He was, the Son of God, it proves Him at least to have been the Son of Man—the unique and unapproachable ideal of humanity, utterly inspired by the Holy Spirit of God.

But again: He condescended, in His teaching of old, to the level of Jewish, knowledge at that time. We may, therefore, believe that He would condescend to the level of our modern knowledge; and what would that involve? It would leave Him, however less than Himself, at least master of all that the human race has thought or discovered in the last eighteen hundred years. Think of that. And think again, that if He condescended, as in Judea of old, to employ that knowledge in teaching men—He who knew what was in man, and needed not that any should bear witness to Him of man—He would manifest a knowledge of human nature to which that of a Shakspeare would be purblind and dull; a knowledge of which the Scripture nobly says that “The Word of God is quick and powerful, and sharper than any two-edged sword, even to the dividing asunder of soul and spirit, and of the joints and marrow, and is a discerner of the thoughts and intents of the heart;” so that all “things are naked and opened unto the eyes of Him with whom we have to do.” And consider that, in the light of that knowledge, He might adapt himself as perfectly to us of this great city, as He did to the villagers of Galilee, or to the townsmen of Jerusalem.

Consider, again, that He who spoke as never man yet spake in Jerusalem, might speak as man never yet spoke on English soil; that He who was listened to gladly once, because He spake with authority, and not as the scribes, at second hand, and by rule and precedent, might be listened to gladly here once more. For He might speak here, not as we poor scribes can speak at best, but with an authority, originality, earnestness, as well as an eloquence, which might exercise a fascination, which would be, to all with whom He came in contact, what Malachi calls it, “a refiner’s fire”—most purifying, though often most painful to the very best; a fascination which might be to every one who came under its spell a veritable Judgment and Day of the Lord, shewing each man with fearful clearness to which side he really inclined at heart in the struggle between truth and falsehood, good and evil; a fascination, therefore, equally attractive to those who wished to do right, and intolerable to those who wished to do wrong.

Consider that last thought. And consider, too, that those to whom the fascination of such a personage might be so intolerable, that it might turn to utter hate, would probably be those whose moral sense was so perverted, that they thought they were doing right when they were doing wrong, and speaking truth when they were telling lies. It is an awful thought. But we know that there were such men, and too many, among the scribes and Pharisees of Jerusalem. And human nature is the same in every age. Be that as it may—however retired His life, He could not long be hid. He would shortly exercise, almost without attempting it, an enormous public influence.

But yet, as in Judea of old, would He not be only too successful? Would He not be at once too liberal for some, and too exacting for others? Would He not, as in Judea of old, encounter not merely the active envy of the vain and the ambitious, which would follow one who spoke as never man spoke; not merely the active malignity of those who wish their fellow-creatures to be bad and not good; not merely the bigotry of every sect and party; but that mere restless love of new excitements, and that dull fear and suspicion of new truths, and even of old truths in new words, which beset the uneducated of every rank and class, and in no age more than in our own? And therefore I must ask, in sober sadness, how long would His influence last? It lasted, we know, in Judea of old, for some three years. And then—. But I am not going to say that any such tragedy is possible now. It would be an insult to Him; an insult to the gracious influences of His Spirit, the gracious teaching of His Church, to say that of our generation, however unworthy we may be of our high calling in Christ. And yet, if He had appeared in any country of Christendom only four hundred years ago, might He not have endured an even more dreadful death than that of the cross?

But doubtless, no personal harm would happen to Him here. Only there might come a day, in which, as in Judea of old, “after He had said these things, many were offended, and walked no more with Him:” when his hearers and admirers would grow fewer and more few, some through bigotry, some through envy, some through fickleness, some through cowardice, till He was left alone with a little knot of earnest disciples; who might diminish, alas, but too rapidly, when they found at He, as in Judea of old, did not intend to become the head of a new sect, and to gratify their ambition and vanity by making them His delegates. And so the world, the religious world as well as the rest, might let Him go His way, and vanish from the eyes and minds of men, leaving behind little more than a regret that one so gifted and so fascinating should have proved—I hardly like to say the words, and yet they must be said—so unsafe and so unsound a teacher.

I shall not give now the reasons which have led me, and not in haste, to this melancholy conclusion. I shall only say that I have come to it, with pain, and shame, and fear. With shame and fear. For when I ask you the solemn question, Would you know Christ if He came among you? do I not ask myself a question which I dare not answer? How can I tell whether I should recognise, after all, my Saviour and my Lord? How do I know that if He said (as He but too certainly might), something which clashed seriously with my preconceived notions of what He ought to say, I should not be offended, and walk no more with Him? How do I know that if He said, as in Judea of old, “Will ye too go away?” I should answer with St Peter, “Lord, to whom shall we go? Thou hast the words of eternal life, and we believe and are sure that thou art the Christ, the Son of the living God?” I dare not ask that question of myself. How then dare I ask it of you? I know not. I can only say, “Lord, I believe: help thou mine unbelief.” I know not. But this I know—that in this or any other world, if you or I did recognise Him, it would be with utter shame and terror, unless we had studied and had striven to copy either Himself, or whatsoever seems to us most like Him. Yes; to study the good, the beautiful, and the true in Him, and wheresoever else we find it—for all that is good, beautiful, and true throughout the universe are nought but rays from Him, the central sun—to obey St. Paul of old, and “whatsoever things are true, venerable, just, pure, lovely, and of good report—if there be any virtue and if there be any praise, to think on these things,”—on these scattered fragmentary sacraments of Him whose number is not two, nor seven, “but seventy-times seven;” that is the way—I think, the only way—to be ready to recognise our Saviour, and to prepare to meet our God; that He may be to us, too, as a refiner’s fire, and refine us—our thoughts, our deeds, our characters throughout.

And I think, too, that this is the way, perhaps the only way, to rid ourselves of the fancy that we can be accounted righteous before God for any works or deservings of our own. Those in whom that fancy lingers must have but a paltry standard of what righteousness is, a mean conception of moral—that is, spiritual—perfection. But those who look not inwards, but upwards; not at themselves, but at Christ and all spiritual perfection—they become more and more painfully aware of their own imperfections. The beauty of Christ’s character shows them the ugliness of their own. His purity shows them their own foulness. His love their own hardness. His wisdom their own folly. His strength their own weakness. The higher their standard rises, the lower falls their estimate of themselves; till, in utter humiliation and self-distrust, they seek comfort ere alone it can be found—in faith—in utter faith and trust in that very moral perfection of Christ which shames and dazzles them, and yet is their only hope. To trust in Him for themselves and all they love. To trust that, just because Christ is so magnificent, He will pity, and not despise, our meanness. Just because He is so pure, and righteous, and true, and lovely, He will appreciate, and not abhor, our struggles after purity, righteousness, truth, love, however imperfect, however soiled with failure—and with worse. Just because He is so unlike us, He will smile graciously upon out feeblest attempts to be like Him. Just because He has borne the sins and carried the sorrows of mankind, therefore those who come to Him He will in no wise cast out. Amen.