___________________________________________________________________________

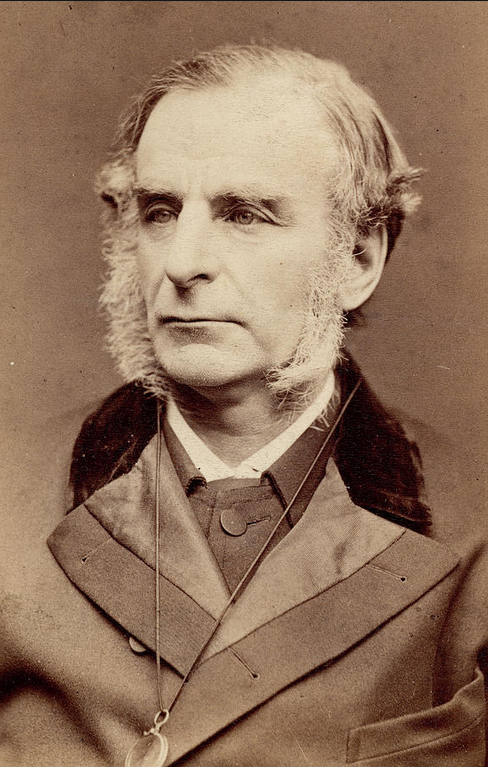

Editor’s note: The following is extracted from All Saints’ Day and Other Sermons, by Charles Kingsley (published 1878).

___________________________________________________________________________

Eversley, 1872. Chester Cathedral, 1872.

St Matt. iv. 3. “And when the tempter came to Him, he said, If Thou be the Son of God, command that these stones be made bread.”

Let me say a few words today about a solemn subject, namely, Temptation. I do not mean the temptations of the flesh—the temptations which all men have to yield to the low animal nature in them, and behave like brutes. I mean those deeper and more terrible temptations, which our Lord conquered in that great struggle with evil which is commonly called His temptation in the wilderness. These were temptations of an evil spirit—the temptations which entice some men, at least, to behave like devils.

Now these temptations specially beset religious men—men who are, or fancy themselves, superior to their fellow-men, more favoured by God, and with nobler powers, and grander work to do, than the common average of mankind. But specially, I say, they beset those who are, or fancy themselves, the children of God. And, therefore, I humbly suppose our Lord had to endure and to conquer these very temptations because He was not merely a child of God, but the Son of God—the perfect Man, made in the perfect likeness of His Father. He had to endure these temptations, and to conquer them, that He might be able to succour us when we are tempted, seeing that He was tempted in like manner as we are, yet without sin.

Now it has been said, and, I think, well said, that what proves our Lord’s three temptations to have been very subtle and dangerous and terrible, is this—that we cannot see at first sight that they were temptations at all. The first two do not look to us to be wrong. If our Lord could make stones into bread to satisfy His hunger, why should He not do so? If He could prove to the Jews that He was the Son of God, their divine King and Saviour, by casting Himself down from the pinnacle of the temple, and being miraculously supported in the air by angels—if He could do that, why should He not do it? And lastly, the third temptation looks at first sight so preposterous that it seems silly of the evil spirit to have hinted at it. To ask any man of piety, much less the Son of God Himself, to fall down and worship the devil, seems perfectly absurd—a request not to be listened to for a moment, but put aside with contempt.

Well, my friends, and the very danger of these spiritual temptations is—that they do not look like temptations. They do not look ugly, absurd, wrong, they look pleasant, reasonable, right.

The devil, says the apostle, transforms himself at times into an angel of light. If so, then he is certainly far more dangerous than if he came as an angel of darkness and horror. If you met some venomous snake, with loathsome spots upon his scales, his eyes full of rage and cunning, his head raised to strike at you, hissing and showing his fangs, there would be no temptation to have to do with him. You would know that you had to deal with an evil beast, and must either kill him or escape from him at once. But if, again, you met, as you may meet in the tropics, a lovely little coral snake, braided with red and white, its mouth so small that it seems impossible that it can bite, and so gentle that children may take it up and play with it, then you might be tempted, as many a poor child has been ere now, to admire it, fondle it, wreathe it round the neck for a necklace, or round the arm for a bracelet, till the play goes one step too far, the snake loses its temper, gives one tiny scratch upon the lip or finger, and that scratch is certain death. That would be a temptation indeed; one all the more dangerous because there is, I am told, another sort of coral snake perfectly harmless, which is so exactly like the deadly one, that no child, and few grown people, can know them apart.

Even so it is with our worst temptations. They look sometimes so exactly like what is good and noble and useful and religious, that we mistake the evil for the good, and play with it till it stings us, and we find out too late that the wages of sin are death. Thus religious people, just because they are religious, are apt to be specially tempted to mistake evil for good, to do something specially wrong, when they think they are doing something specially right, and so give occasion to the enemies of the Lord to blaspheme; till, as a hard and experienced man of the world once said: “Whenever I hear a man talking of his conscience, I know that he is going to do something particularly foolish; whenever I hear of a man talking of his duty, I know that he is going to do something particularly cruel.”

Do I say this to frighten you away from being religious? God forbid. Better to be religious and to fear and love God, though you were tempted by all the devils out of the pit, than to be irreligious and a mere animal, and be tempted only by your own carnal nature, as the animals are. Better to be tempted, like the hermits of old, and even to fall and rise again, singing, “Rejoice not against me, O mine enemy, when I fall I shall arise;” than to live the life of the flesh, “like a beast with lower pleasures, like a beast with lower pains.” It is the price a man must pay for hungering and thirsting after righteousness, for longing to be a child of God in spirit and in truth. “The devil,” says a wise man of old, “does not tempt bad men, because he has got them already; he tempts good men, because he has not got them, and wants to get them.”

But how shall we know these temptations? God knows, my friends, better than I; and I trust that He will teach you to know, according to what each of you needs to know. But as far as my small experience goes, the root of them all is pride and self-conceit. Whatsoever thoughts or feelings tempt us to pride and self-conceit are of the devil, not of God. The devil is specially the spirit of pride; and, therefore, whatever tempts you to fancy yourself something different from your fellow-men, superior to your fellow men, safer than them, more favoured by God than them, that is a temptation of the spirit of pride. Whatever tempts you to think that you can do without God’s help and God’s providence; whatever tempts you to do anything extraordinary, and show yourself off, that you may make a figure in the world; and above all, whatever tempts you to antinomianism, that is, to fancy that God will overlook sins in you which He will not overlook in other men—all these are temptations from the spirit of pride. They are temptations like our Lord’s temptations. These temptations came on our Lord more terribly than they ever can on you and me, just because He was the Son of Man, the perfect Man, and, therefore, had more real reason for being proud (if such a thing could be) than any man, or than all men put together. But He conquered the temptations because He was perfect Man, led by the Spirit of God; and, therefore, He knew that the only way to be a perfect man was not to be proud, however powerful, wise, and glorious He might be; but to submit Himself humbly and utterly, as every man should do, to the will of His Father in Heaven, from whom alone His greatness came.

Now the spirit of pride cannot understand the beauty of humility, and the spirit of self-will cannot understand the beauty of obedience; and, therefore, it is reasonable to suppose the devil could not understand our Lord. If He be the Son of God, so might Satan argue, He has all the more reason to be proud; and, therefore, it is all the more easy to tempt Him into shewing His pride, into proving Himself a conceited, self-willed, rebellious being—in one word, an evil spirit.

And therefore (as you will see at first sight) the first two temptations were clearly meant to tempt our Lord to pride; for would they not tempt you and me to pride? If we could feed ourselves by making bread of stones, would not that make us proud enough? So proud, I fear, that we should soon fancy that we could do without God and His providence, and were masters of nature and all her secrets. If you and I could make the whole city worship and obey us, by casting ourselves off this cathedral unhurt, would not that make us proud enough? So proud, I fear, that we should end in committing some great folly, or great crime in our conceit and vainglory.

Now, whether our Lord could or could not have done these wonderful deeds, one thing is plain—that He would not do them; and, therefore, we may presume that He ought not to have done them. It seems as if He did not wish to be a wonderful man: but only a perfectly good man, and He would do nothing to help Himself but what any other man could do. He answered the evil spirit simply out of Scripture, as any other pious man might have done. When He was bidden to make the stones into bread, He answers not as the Eternal Son of God, but simply as a man. “It is written:”—it is the belief of Moses and the old prophets of my people that man doth not live by bread alone, but by every word that proceedeth out of the mouth of God:—as much as to say, If I am to be delivered out of this need, God will deliver me by some means or other, just as He delivers other men out of their needs. When He was bidden cast Himself from the temple, and so save Himself, probably from sorrow, poverty, persecution, and the death on the cross, He answers out of Scripture as any other Jew would have done. “It is written again, Thou shalt not tempt the Lord thy God.” He says nothing—this is most important—of His being the eternal Son of God. He keeps that in the background. There the fact was; but He veiled the glory of His godhead, that He might assert the rights of His manhood, and shew that mere man, by the help of the Spirit of God, could obey God, and keep His commandments.

I say these last words with all diffidence and humility, and trusting that the Lord will pardon any mistake which I may make about His Divine Words. I only say them because wiser men than I have often taken the same view already. Of course there is more, far more, in this wonderful saying than we can understand, or ever will understand. But this I think is plain—that our Lord determined to behave as any and every other man ought to have done in His place; in order to shew all God’s children the example of perfect humility and perfect obedience to God.

But again, the devil asked our Lord to fall down and worship him. Now how could that be a temptation to pride? Surely that was asking our Lord to do anything but a proud action, rather the most humiliating and most base of all actions. My friends, it seems to me that if our Lord had fallen down and worshipped the evil spirit, He would have given way to the spirit of pride utterly and boundlessly; and I will tell you why.

The devil wanted our Lord to do evil that good might come. It would have been a blessing, that all the kingdoms of the world and the glory of man should be our Lord’s,—the very blessing for this poor earth which He came to buy, and which He bought with His own precious blood. And here the devil offered Him the very prize for which He came down on earth, without struggle or difficulty, if He would but do, for one moment, one wrong thing. What temptation that would be to our Lord as God, I dare not say. But that to our Lord as Man, it must have been the most terrible of all temptations, I can well believe: because history shews us, and, alas! our own experience in modern times shews us, persons yielding to that temptation perpetually; pious people, benevolent people, people who long to spread the Bible, to convert sinners, to found charities, to amend laws, to set the world right in some way or other, and who fancy that therefore, in carrying out their fine projects, they have a right to do evil that good may come.

This is a very painful subject; all the more painful just now, because I sometimes think it is the special sin of this country and this generation, and that God will bring on us some heavy punishment for it. But all who know the world in its various phases, and especially what are called the religious world, and the philanthropic world, and the political world, know too well that men, not otherwise bad men, will do things and say things, to carry out some favourite project or movement, or to support some party, religious or other, which they would (I hope) be ashamed to say and do for their own private gain. Now what is this, but worshipping the evil spirit, in order to get power over this world, that they may (as they fancy) amend it? And what is this but self-conceit—ruinous, I had almost said, blasphemous? These people think themselves so certainly in the right, and their plans so absolutely necessary to the good of the world, that God has given them a special licence to do what they like in carrying them out; that He will excuse in them falsehoods and meannesses, even tyranny and violences which He will excuse in no one else.

Now, is not this self-conceit? What would you think of a servant who disobeyed you, cheated you, and yet said to himself—No matter, my master dare not turn me off: I am so useful that he cannot do without me. Even so in all ages, and now as much as, or more than ever, have men said, We are so necessary to God and God’s cause, that He cannot do without us; and therefore though He hates sin in everyone else, He will excuse sin in us, as long as we are about His business.

Therefore, my dear friends, whenever we are tempted to do or say anything rash, or vain, or mean, because we are the children of God; whenever we are inclined to be puffed up with spiritual pride, and to fancy that we may take liberties which other men must not take, because we are the children of God; let us remember the words of the text, and answer the tempter, when he says, If thou be the Son of God, do this and that, as our Lord answered him—“If I be the Child of God, what then? This—that I must behave as if God were my Father. I must trust my God utterly, and I must obey Him utterly. I must do no rash or vain thing to tempt God, even though it looks as if I should have a great success, and do much good thereby. I must do no mean or base thing, nor give way for a moment to the wicked ways of this wicked world, even though again it looks as if I should have a great success, and do much good thereby. In one word, I must worship my Father in heaven, and Him only must I serve. If He wants me, He will use me. If He does not want me, He will use some one else. Who am I, that God cannot govern the world without my help? My business is to refrain my soul, and keep it low, even as a weaned child, and not to meddle with matters too high for me. My business is to do the little, simple, everyday duties which lie nearest me, and be faithful in a few things; and then, if Christ will, He may make me some day ruler over many things, and I shall enter into the joy of my Lord, which is the joy of doing good to my fellow men. But I shall never enter into that by thrusting myself into Christ’s way, with grand schemes and hasty projects, as if I knew better than He how to make His kingdom come. If I do, my pride will have a fall. Because I would not be faithful over a few things, I shall be tempted to be unfaithful over many things; and instead of entering into the joy of my Lord, I shall be in danger of the awful judgment pronounced on those who do evil that good may come, who shall say in that day, Lord, Lord, have we not prophesied in thy name? and in thy name cast out devils? and in thy name done many wonderful works? And then will He protest unto them—”I never knew you. Depart from me, ye that work iniquity.”

Oh, my friends, in all your projects for good, as in all other matters which come before you in your mortal life, keep innocence and take heed to the thing that is right. For that, and that alone, shall bring a man peace at the last.

To which, may God in His mercy bring us all. Amen.