Editor’s note: The following is extracted from True Heroism and Other Sermons, by R. N. Sledd (published 1899).

“The joy of the Lord is your strength.” — Nehemiah viii, 10.

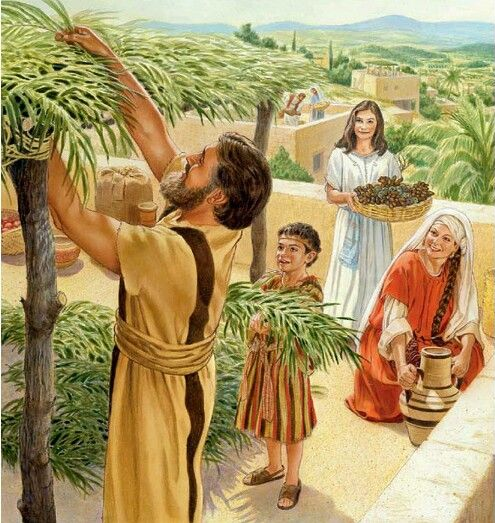

There was a statute of the Mosaic code which required that the whole Law should be read to the people once in every seven years. The time appointed for this reading was during the celebration of the Feast of Tabernacles. This provision necessarily fell into neglect during the captivity. Its restoration is recorded in this chapter.

The people having gathered themselves together, Ezra the scribe, standing on a platform which had been made for the purpose, read in their hearing the Book of the Law of Moses, continuing the reading from day to day until the whole was completed. The language of the people had undergone a very material change during the captivity. They now spoke, for the most part, the Chaldee dialect. Hence, while Ezra read from the old Hebrew text, twelve Levites served as interpreters — translating the Law as he read into the Chaldee, and accompanying the translation with such explanations as were necessary to convey the sense to the people.

The reading occasioned great sorrow and weeping. The people saw in how many things they had transgressed the law of God. They heard the curses denounced against transgressors. And, although they had done these things ignorantly, they were overwhelmed with grief, and with fears of punishment.

It was a good sign that their hearts were so tender and so deeply affected by the word of God. But their mourning was unseasonable. The day was “holy unto the Lord.” It was one of their great religious festivals and ought to be celebrated with joy and praise. They were therefore dismissed with an exhortation to put away their sorrow, and eat and drink, and send portions to the needy, and keep the feast with the cheerfulness of spirit and deportment becoming such an occasion.

And there is a reason for the exhortation yet more profound and comprehensive. They were engaged in an enterprise of vast moment to themselves and their posterity. The abuses of a century of neglect and of constantly increasing ignorance and wickedness were to be corrected. The worship of their fathers was to be restored in its purity. Their city was to be rebuilt and the desolations of the country reclaimed. They were comparatively few in number, very feeble, and greatly impoverished, while their adversaries were numerous, powerful and vigilant. And their success could be assured only by the careful husbandry and concentration of all their moral as well as physical forces. Great grief bows the head, oppresses the heart, enfeebles the will, and disqualifies one for vigorous, well-sustained effort and great achievement. It is the cheerful, glad spirit that can dare, and do, and suffer great things. In recognition of this truth, Nehemiah gives as an additional reason why their grief should be restrained and put away that there is an element of power in religious joy with which, in view of their circumstances and the work before them, they could not afford to dispense. “The joy of the Lord is your strength.” The best of all equipments for successful working and warring — better than the walls and towers which we have built, better than the soldiers we have marshaled and the munitions we have gathered, is the spirit of rejoicing in God.

This thought, under the divine blessing, may be of practical value to us. How to live successfully, how to fill up the measure of our responsibility by wielding the largest influence and accomplishing the best results of which we are capable, is the most important of all questions to us as moral beings. May we not find here — in “the joy of the Lord” — our greatest strength, our supreme qualification for our work? Is there not some point in the moral and spiritual world or some state of gracious attainment, where we may bring into the very fullest and most effective exercise the wondrous forces with which God has endowed us? And may it not be that in “the joy of the Lord” we may find this hiding-place of power? The question certainly merits attention. Let us examine it.

“The joy of the Lord.” The expression is unusual, it does not often occur in the Scriptures. It may denote either the joy of the Lord in His people, or His people’s joy in Him. Both ideas are scriptural. The first is a precious revelation; the second is a precious experience. He delights in and rejoices over His people; and His people rejoice in the Lord and joy in the God of their salvation. Their experience of this joy, however, rests on the revelation of His love made to the soul by the Holy Ghost. When with unquestioning trust in the Son of God a man grasps and appropriates the blessed truth of present forgiveness and salvation through Him, “the Spirit itself beareth witness with his spirit that he is a child of God.” With such a testimony, how can he do otherwise than “magnify the Lord” and rejoice in Him? Any other sentiment than that of love, any other language than that of praise would be unnatural and strange.

This joy in God as our Father, reconciled unto us through Jesus Christ, and imparting to us by the Holy Ghost the assurance of His love for us and His delight in us, is our strength.

I. The antecedent conditions on which the soul comes to the experience of this joy are conditions essential to the exercise of its greatest moral power. They are conditions of strength as well as of joy. What are they?

1. A complete and final renunciation of sin. We would not affirm that those who love and live in sin are necessarily strangers to all joy. We know, on the contrary, that those who neither fear God nor regard man, may and often do experience the liveliest emotions of joy in the pursuit and attainment of their ends. Their joys may be short lived and unsatisfactory; but they are to them real joys. But we do mean to affirm that Christian joy and sin are utterly incompatible. They can no more dwell together in the same heart than the most delicate flower of the tropics can bloom amid the eternal snows of the North, or the human body preserve its health and vigor with the deadly venom of the cobra poisoning every drop of its blood. This joy is possible only when the soul has broken away from “the abominable thing that God hateth,” and can survive only so long as the soul maintains its integrity and uprightness before God.

While sin is thus fatal to Christian joy, it is also an element of weakness. It saps the very foundations of human strength. No man is strong in whom and over whom sin reigns. He may in spite of it accomplish grand results in life; but oftener than otherwise his slavery to petty vices of temper or speech, or grosser vices of debauchery and excess will demonstrate his weakness. Alexander could conquer the world, but was himself conquered and slain by a sensual appetite. And how often have we seen the man of the world after the most brilliant intellectual triumph too weak to refuse the intoxicating cup. Sin is essentially enfeebling, disorganizing, destructive; and “when it is finished it bringeth forth death,” which is the utter negation of all power, “the breathless region of absolute and eternal faintness.”

The first and necessary condition of this joy, therefore, is the putting away of that which is the chief source of the soul’s weakness. It is the stripping of the athlete for the race, the loosing of the fetters of the giant, the slaying of the serpents that “crush, and enervate, and spoil the spirit,” the clearing away of the rust and gum from the axles and pistons, and the dead ashes and cinders from the furnace of the engine, and fitting it for its highest speed and greatest power. And until these fetters are broken, these serpents slain, and “every weight and the sin that doth so easily beset” laid aside, the soul cannot hope for success in the work and struggles of the Christian life.

2. A second antecedent condition of this joy is the reception of the revelation of God — especially the revelation of His grace in Christ — as infallible and absolute truth. The world is full of questionings at this point. The seriousness of such questionings, or the reality of such doubts, invariably marks the absence of Christian joy. The cry of the afflicted father: “Lord, I believe: help thou mine unbelief,” always antedates the birth of joy; and it can live in the soul only so long as that soul reposes on the word of God as an eternal verity.

That word touches us at every point of our being — at every step of our life. It settles the questions of our relations to God and our fellow men, of our responsibility and destiny; it discovers the only refuge for human guilt, the only remedy for human woe, the only satisfaction for human longings. In its light alone can we see light, and walk in conscious safety amid the perplexities of life, and through the shadows of death up to glory, honor, and immortality. Put it aside as unworthy of absolute trust, and the soul is abroad on a sea of storms and shoals without anchor, chart, or compass, or the twinkle of a single star to cheer its midnight. It has no joy, no hope.

Doubt is little less friendly to strength than it is to joy. Illustrations of its paralyzing effects may be drawn from every position and vocation in life. Who are the world’s successful men? Who its greatest warriors, statesmen, jurists; its immortal artists, poets, historians, philosophers; its merchant princes, its inventors, its illustrious benefactors? Surely not the doubting, halting, hesitating; but the men of firm conviction, and determined purpose. These have been crowned with success, while those who have lived amid the somber shades and unwholesome vapors of distrust have sunk down benumbed and sluggish and comparatively powerless.

Distrust of the truth of God operates in the same way. It generates vacillation and weakness with respect to the duties which that truth enjoins, and the ends it proposes, and culminates in complete moral impotency and death.

Thus before we reach the joy itself, in its two an tecedent conditions — the puting away of sin and the acceptance and appropriation of God’s revelation of mercy and salvation — we find two prime conditions of strength.

II. In the necessary ingredients of this joy — in those grand truths of experience that enter as component factors into this joy — there is strength. What are these?

1. Reconciliation — the adjustment of all our moral and spiritual relations. These have all been disturbed by sin. There is disturbance in our souls — confusion, discord, darkness. There is disturbance between us and our right position, work and end in the economy of God. We have abandoned that position, refused that work, and are at war with the beneficent purposes of our being. There is disturbance between us and our Maker. We have broken away from His authority. We have put on the uniform and the arms of His adversary. We have provoked Him to jealousy and exposed ourselves to His righteous displeasure. There is disturbance between us and all holy beings. We are at variance with the virtuous universe — a discordant note in its music — a jar in the sublime harmony of its movements.

But with broken and contrite hearts we come to God through Christ, and the cause of this wide-spread disturbance is at once removed. Our sin is forgiven, our souls are washed in the blood of the Lamb, and by the power of the Holy Ghost we are renewed after the image of Him that created us “in righteousness and true holiness.” There is now peace within. Reason, conscience, sensibility, will, each resumes its rightful place, each exercises its rightful functions. There is peace with God. Though He was angry with us, His anger is all turned away and He comforts us. He takes us into His arms and into His heart, and cherishes us even as a mother cherishes her first-born. There is peace, sympathy, fellowship with all holy beings in heaven and on earth. We have come to “an innumerable company of angels, and to the spirits of just men made perfect, and to the general assembly and church of the first-born which are written in heaven.” “One family we dwell in Him” — each rejoicing in the same blessed hope, and guided by the same hand to the same glorious destiny.

Oh, there must be strength in such a union! The material universe with its thousands of ponderous worlds is sweeping with resistless might through the fields of space. Every sun, moon, and star, impelled by the same wondrous force, is on the march, each helping to hold the other in its place and urging it on in its course. Any external force that could hurl one sphere from its orbit must be mightier than the forces that bind together, uphold and move all, and therefore might arrest the movement of all and wreck the whole system. So in the moral and spiritual universe, to which the soul now reconciled and joyful in God belongs, there is movement, onward, upward glorious movement. “The principalities and powers in the heavenly places,” “the saints to glory gone,” the saints on earth, are all stirred and moved by an impulse more potent than gravitation and all its kindred forces — the sweet, blessed impulse of the life and love of God. And any power that could overcome and destroy one soul reconciled and rightly adjusted to its position and relations in the system of God, may overcome all other beings in that system because it overcomes the combined forces that up hold and move all. If such a result be inconceivable, then in this adjustment of all our moral and spiritual relations there is strength; in reconciliation perpetuated by unfaltering trust there is invincible might.

2. Assurance; that blessed conviction wrought in the soul by the Holy Ghost, that all the grace of the covenant is ours — not that salvation is something which we may hope to obtain at some indefinite future time, but that we are already saved — that God is now our Father, Jesus our Saviour, the Holy Ghost our Comforter, heaven our inheritance. Such assurance is not only the privilege of the soul, but is necessary to its joy in God. It is the chief ingredient of this joy — that without which it cannot exist. This is that joy of salvation for which David prayed so earnestly, and which every gracious soul esteems its most precious boon.

And who can estimate the strength of such assurance? In the concerns of this life assurance is one chief element of success. He who is assured of the righteousness of his cause, or the correctness of his views, or the practicability and utility of his plans, or his ability to accomplish his ends, will achieve results that otherwise would be wholly beyond his reach. In the higher region of the spiritual the power with which it nerves the soul for work and endurance is limited only by the frailties of the body. It enabled “the father of the faithful” to relinquish all the endearments of his ancestral home, and to go out he knew not whither to live as a pilgrim and stranger in a strange land, and to surrender the child of promise to the altar of sacrifice. Assured of his divine call and of the friendship of God, he stands out in the world’s history as one of God’s mightiest men. In the apostle of the Gentiles it was stronger than death and sweeter than life. With the prophecy of bonds and imprisonment in his heart, he could say : “None of these things move me, neither count I my life dear unto myself so that I might finish my course with joy and the ministry which I have received to testify the gospel of the grace of God;” and he rises to a still grander height, if possible, when he exclaims, “I can do all things through Jesus Christ which strengtheneth me.”

And in the ordinary walks of Christian life, no less than in the history of these illustrious servants of God, may we find demonstrations of the power of this grace. We have seen the mother bending with streaming eyes and almost breaking heart over the lifeless form of her only child, and covering the cold brow with the kisses of maternal love and grief. But hear her: “O God, I would not, do not murmur or repine. The cup is bitter, but in thy strength I drink it. The Lord gave and the Lord hath taken away; blessed be the name of the Lord.” There in that humble home, in deepest poverty, is a dying servant of God. The love of Christ is in his heart; he rejoices in the assurance of hope; see! the light of heaven is already on his brow; with a thrilling shout of victory he ascends to his throne. O what are the possessions of this world, what its pleasures, what its garlands and trumpets of fame, when cast into the scale against the assurance that I am God’s and He is mine! With it, though troubled on every side, I will not be distressed; though perplexed, I will not be in despair; though sorrowful, yet will I be always rejoicing.

With a scrip on my back and a staff in my hand,

I’ll march on in haste through an enemy’s land,

The road may be rough, but it cannot be long,

I’ll smooth it with hope, and I’ll cheer it with song.

3. A lively hope. Joy is prospective. It is not simply a present fruition; but as its inspiration comes from within the vail, so it looks forward to the future and upward to the heavenly home for its final consummation. This prospective element is hope, and without it Christian joy has no existence. And is there no power in such a hope? Was not Abraham sustained and cheered in his pilgrimage by the hope of “a better country that is an heavenly” — “a city which hath foundations whose maker and builder is God?” Did not Moses, when he bade adieu to the court of Egypt and “chose rather to suffer afflictions with the people of God,” have “respect unto the recompense of the reward?” And it is written of a greater than either of these that for the joy that was set before Him He endured the cross, despising the shame. And there are no crosses we cannot bear, no buffetings we cannot endure, no perils we cannot brave in the strength of the hope of heaven. Why need we be discouraged because of the way? What though the waters of Marah be bitter and the valley of Baca be dry? What though every flower of earthly love whither and perish, and friends all fail and foes all unite? In a little while the wilderness with its privations, its toils and its tears will be passed, the river will be crossed and we will be at home. “Blessed be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ which, according to His abundant mercy, hath begotten us again, by the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead, unto a lively hope to an inheritance which is incorruptible, undefiled, and that fadeth not away.”

And now out of these three, reconciliation, assurance, hope — comes as a grand resultant “the joy of the Lord.” In each of these there is strength; in all combined there is all we can need for a successful Christian life. There is strength for whatever work God has for us to do, strength for defence against whatever foes may assail us, and for the endurance of whatever ills may overtake us — strength to toil and suffer, and strength to die in holy triumph, and on wings of gladness swifter, than the light “soar away to sing God’s praise in endless day.”

Everyone needs this strength for the work of life. The cultivation and enrichment of our intellectual powers, of the aesthetic elements of our nature, and of all the tender sweet affections of the heart, cannot supersede the necessity of the inspiration and power that come from the life which is hid with Christ in God. Take the living Christ into your trusting, loving heart. Live in Him; live on Him; live for Him,

“And your life will be all sunshine

In the sweetness of your Lord.”