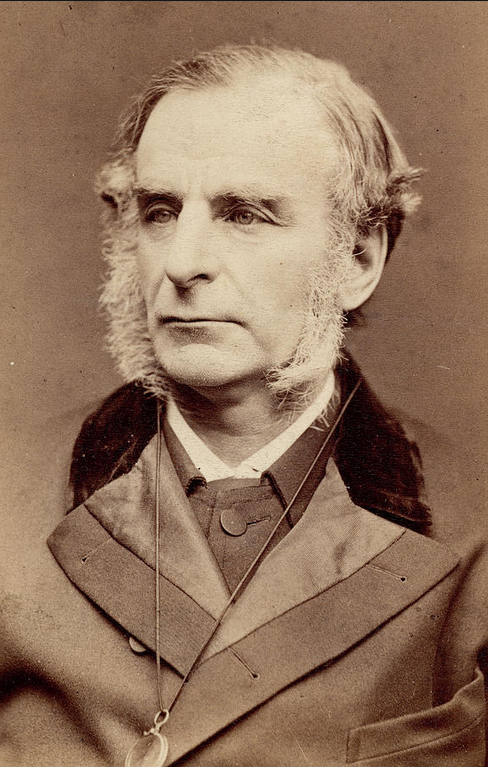

Editor’s note: The following is extracted from The Good News of God, by Charles Kingsley (published 1887).

Psalm vii. 8.

Give sentence for me, O Lord, according to my righteousness; and according to the innocency that is in me.

Is this speech self-righteous? If so, it is a bad speech; for self-righteousness is a bad temper of mind; there are few worse. If we say that we have no sin, we deceive ourselves, and the truth is not in us. If we confess our sins, God is faithful and just to forgive us our sins, and to cleanse us from all unrighteousness. If we say that we have not sinned, we make him a liar.

This is plain enough; and true as God is true. But there is another temper of mind which is right in its way; and which is not self-righteousness, though it may look like it at first sight. I mean the temper of Job, when his friends were trying to prove to him that he must be a bad man, and to make him accuse himself of all sorts of sins which he had not committed; and he answered that he would utter no deceit, and tell no lies about himself. ‘Till I die I will not remove mine integrity from me; my righteousness I will hold fast, and will not let it go; my heart shall not reproach me as long as I live.’ I have, on the whole, tried to be a good man, and I will not make myself out a bad one.

For, my friends, with the Bible as with everything else, we must hear both sides of the question, lest we understand neither side.

We may misuse St. John’s doctrine, that if we say we have no sin, we deceive ourselves. We may deceive ourselves in the very opposite way.

In the first place, some people, having learnt that it is right to confess their sins, try to have as many sins as possible to confess. I do not mean that they commit the sins, but that they try to fancy they have committed them. This is very common now, and has been for many hundred years, especially among young women and lads who are of a weakly melancholy temper, or who have suffered some great disappointment. They are fond of accusing themselves; of making little faults into great ones; of racking their memories to find themselves out in the wrong; of taking the darkest possible view of themselves, and of what is going to happen to them. They forget that Solomon, the wise, when he says, ‘Be not over-much wicked; neither be thou foolish—why shouldst thou die before thy time?’—says also, ‘Be not righteous over-much; neither make thyself over-wise. Why shouldst thou destroy thyself?’

For such people do destroy themselves. I have seen them kill their own bodies, and die early, by this folly. And I have seen them kill their own souls, too, and enter into strong delusions, till they believe a lie, and many lies, from which one had hoped that the Bible would have delivered any and every man.

One cannot be angry with such people. One can only pity them, and pity them all the more, when one finds them generally the most innocent, the very persons who have least to confess. One can but pity them, when one sees them applying to themselves God’s warnings against sins of which they never even heard the names, and fancying that God speaks to them, as St. Paul says that he did to the old heathen Romans, when they were steeped up to the lips in every crime.

No—one can do more than pity them. One can pray for them that they may learn to know God, and who he is: and by knowing him, may be delivered out of the hands of cunning and cruel teachers, who make a market of their melancholy, and hide from them the truth about God, lest the truth should make them free, while their teachers wish to keep them slaves.

This is one misuse of St. John’s doctrine. There is another and a far worse misuse of it.

A man may be proud of confessing his sins; may become self-righteous and conceited, according to the number of the sins which he confesses.

So deceitful is this same human heart of ours, that so it is I have seen people quite proud of calling themselves miserable sinners. I say, proud of it. For if they had really felt themselves miserable sinners, they would have said less about their own feelings. If a man really feels what sin is—if he feels what a miserable, pitiful, mean thing it is to be doing wrong when one knows better, to be the slave of one’s own tempers, passions, appetites—oh, if man or woman ever knew the exceeding sinfulness of sin, he would hide his own shame in the depths of his heart, and tell it to God alone, or at most to none on earth save the holiest, the wisest, the trustiest, the nearest and the dearest.

But when one hears a man always talking about his own sinfulness, one suspects—and from experience one has only too much reason to suspect—that he is simply saying in a civil way, ‘I am a better man than you; for I talk about my sinfulness, and you do not.’

For if you answer such a man, as old Job or David would have done, ‘I will not confess what I have not felt. I have tried and am trying to be an upright, respectable, sober, right-living man. Let God judge me according to the innocency that is in me. I know that I am not perfect: no man is that: but I will not cant; I will not be a hypocrite; and if I accuse myself of sins which I have not committed, it seems to me that I shall be mocking God, and deceiving myself. I will trust to God to judge me fairly, to balance between the good and the evil which is in me, and deal with me accordingly.’

If you speak in that way, the other man will answer you plainly enough, ‘Ah! you are utterly benighted. You are building on legality and morality. You have not yet learnt the first principles of the Gospel.’ And with these, and other words, will give you to understand this—That he thinks he is going to heaven, and you are going to hell.

Now, my dear friends, you are partly right, and he is partly right. St. Paul will show you where you are right and where he is right. He does so, I think, in a certain noble text of his in which he says, ‘I judge not mine own self; for I know nothing against myself, yet am I not hereby justified: but he that judgeth me is the Lord.’

Now remember that no man was less self-righteous than St. Paul. No man ever saw more clearly the sinfulness of sin. No man ever put into words so strongly the struggle between good and evil which goes on in the human heart. In one place, even, when speaking of his former life, he calls himself the chief of sinners. Yet St. Paul, when he had done his duty, knew that he had done it, and was not afraid to say—as no honest and upright man need be afraid to say—‘I know nothing against myself.’ For if you have done right, my friend, it is God who has helped you to do it; and it is difficult to see how you can honour God, by pretending instead that he has left you to do wrong.

This, then, seems to be the rule. If you have done wrong, be not afraid to confess it. If you have done right, be not afraid to confess that either. And meanwhile keep up your self-respect. Try to do your duty. Try to keep your honour bright. Let no man be able to say that he is the worse for you. Still more let no woman be able to say that she is the worse for you; for if you treat another man’s daughter as you would not let him treat yours, where is your honour then, or your clear conscience? What cares man, what cares God, for your professions of uprightness and respectability, if you take good care to behave well to men, who can defend themselves, and take no care to behave well to a poor girl, who cannot defend herself? Recollect that when Job stood up for his own integrity, and would not give up his belief that he was a righteous man, he took care to justify himself in this matter, as well as on others. ‘I made a covenant with mine eyes,’ he says; ‘why then should I think upon a maid? If mine heart have been deceived by a woman; or if I have laid wait at my neighbour’s door;’ ‘Then,’ he says in words too strong for me to repeat, ‘let others do to my wife as I have done to theirs.’

Avoid this sin, and all sins. Let no man be able to say that you have defrauded him, that you have tyrannized over him; that you have neglected to do your duty by him. Let no man be able to say that you have rewarded him evil for evil. If possible, let him not be able to say that you have even lost your temper with him. Be generous; be forgiving. If you have an opportunity, be like David, and help him who without a cause is your enemy; and then you will have a right to say, like David, ‘Give sentence with me, O Lord, according to my righteousness, and according to the cleanness of my hands in thy sight.’

True—that will not justify you. In God’s sight shall no man living be justified, if justification is to come by having no faults. What man is there who lives, and sins not? Who is there among us, but knows that he is not the man he might be? Who does not know, that even if he seldom does what he ought not, he too often leaves undone what he ought? And more than that—none of us but does many a really wrong thing of which he never knows, at least in this life. None of us but are blind, more or less, to our own faults; and often blind—God forgive us!—to our very worst faults.

Then let us remember, that he who judges us is the Lord.

Now is that a thought to be afraid of?

David did not think so, when he had done right. For he says, in this Psalm, ‘Judge me, O Lord!’

And when he has done wrong, he thinks so still less; for then he asks God all the more earnestly, not only to judge him, but to correct him likewise. ‘Purge me,’ he says, ‘and I shall be clean. Cleanse thou me from my secret faults, and make me to understand wisdom secretly. For thou requirest truth in the inward parts.’

That is bravely spoken, and worthy of an honest man, who wishes above all things to be right, whatsoever it may cost him.

But how did David get courage to ask that?

By knowing God, and who God was.

For this, my friends, is the key to the whole matter—as it is to all matters—Who is God?

If you believe God to be a hard task-master, and a cruel being, extreme to mark what is done amiss, an accuser like the devil, instead of a forgiver and a Saviour, as he really is;—then you will begin judging yourself wrongly and clumsily, instead of asking God to judge you wisely and well.

You will break both of the golden rules which St. Anthony, the famous hermit, used to give to his scholars.—‘Regret not that which is past; and trust not in thine own righteousness.’ For you will lose time, and lose heart, in fretting over old sins and follies, instead of confessing them once and for all to God, and going boldly to his throne of grace to find mercy and grace to help you in the time of need; that you may try again and do better for the future. And so it will be true of you—I am sure I have seen it come true of many a poor soul—what David found, before he found out the goodness of God’s free pardon:—‘While I held my tongue, my bones waxed old through my daily complaining. For thy hand was heavy upon me night and day; my moisture was like the drought in summer.’

And all that while (such contradictory creatures are we all), you may be breaking St. Anthony’s other golden rule, and trusting in your own righteousness.

You will begin trying to cleanse yourself from little outside faults, and fancying that that is all you have to do, instead of asking God to cleanse you from your secret faults, from the deep inward faults which he alone can see; forgetting that they are the root, and the outside faults only the fruit. And so you will be like a foolish sick man, who is afraid of the doctor, and therefore tries to physic himself. But what does he do? Only tamper and peddle with the outside symptoms of his complaint, instead of going to the physician, that he may find out and cure the complaint itself. Many a man has killed his own body in that way; and many a man more, I fear, has killed his own soul, because he was afraid of going to the Great Physician.

But if you will believe that God is good, and not evil; if you will believe that the heavenly Father is indeed your Father; if you will believe that the Lord Jesus Christ really loves you, really died to save you, really wishes to deliver you from your sins, and make you what you ought to be, and what you can be: then you will have heart to do your duty; because you will be sure that God helps you to do your duty. You will have heart to fight bravely against your bad habits, instead of fretting cowardly over them; because you know that God is fighting against them for you. You will not, on the other hand, trust in your own righteousness; because you will soon learn that you have no righteousness of your own: but that all the good in you comes from God, who works in you to will and to do of his good pleasure.

And when you examine yourself, and think over your own life and character, as every man ought to do, especially in Advent and Lent, you will have heart to say, ‘O God, thou knowest how far I am right, and how far wrong. I leave myself in thy hand, certain that thou wilt deal fairly, justly, lovingly with me, as a Father with his son. I do not pretend to be better than I am: neither will I pretend to be worse than I am. Truly, I know nothing about it. I, ignorant human being that I am, can never fully know how far I am right, and how far wrong. I find light and darkness fighting together in my heart, and I cannot divide between them. But thou canst. Thou knowest. Thou hast made me; thou lovest me; thou hast sent thy Son into the world to make me what I ought to be; and therefore I believe that he will make me what I ought to be. Thou willest not that I should perish, but come to the knowledge of the truth: and therefore I believe that I shall not perish, but come to the knowledge of the truth about thee, about my own character, my own duty, about everything which it is needful for me to know. And therefore I will go boldly on, doing my duty as well as I can, though not perfectly, day by day; and asking thee day by day to feed my soul with its daily bread. Thou feedest my soul with its daily bread. How much more then wilt thou feed my mind and my heart, more precious by far than my body? Yes, I will trust thee for soul and for body alike; and if I need correcting for my sins, I am sure at least of this, that the worst thing that can happen to me or any man, is to do wrong and not to be corrected; and the best thing is to be set right, even by hard blows, as often as I stray out of the way. And therefore I will take my punishment quietly and manfully, and try to thank thee for it, as I ought; for I know that thou wilt not punish me beyond what I deserve, but far below what I deserve; and that thou wilt punish me only to bring me to myself, and to correct me, and purge me, and strengthen me. For this I believe—on the warrant of thine own word I believe it—undeserved as the honour is, that thou art my Father, and lovest me; and dost not afflict any man willingly, or grieve the children of men out of passion or out of spite; and that thou willest not that I should be damned, nor any man; but willest have all men saved, and come to the knowledge of the truth.’

Thanks again for posting these sermons by Charles Kingsley. This is so helpful. He really ties it all together. An excellent expositor!