Editor’s note: The following is extracted from True Heroism and Other Sermons, by R. N. Sledd (published 1899).

“There were present at that season some that told Him of the Galileans, whose blood Pilate had mingled with their sacrifices. And Jesus answering said unto them, Suppose ye that these Galileans were sinners above all the Galileans, because they suffered such things? I tell you, Nay: but except ye repent, ye shall all likewise perish. Or those eighteen, upon whom the tower in Siloam fell, and slew them, think ye that they were sinners above all men that dwelt in Jerusalem? I tell you, Nay: but, except ye repent, ye shall all likewise perish.” — Luke xiii, 1-5.

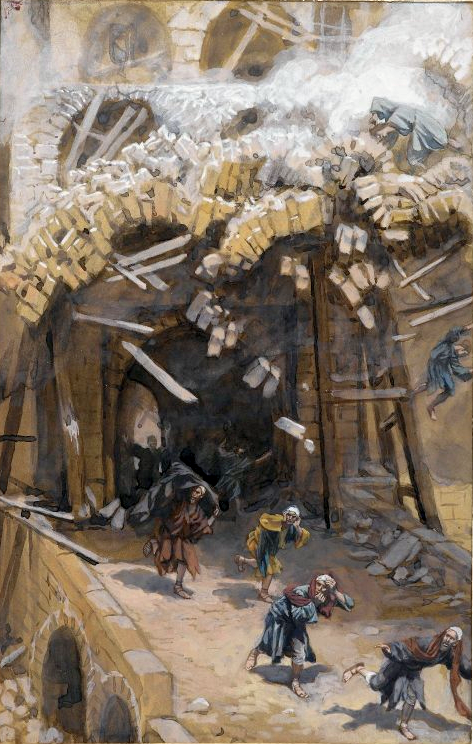

We have in the text a record of two historical facts: The slaying of certain Galileans by Pilate while they were offering their sacrifices, and the killing of eighteen men by the falling of a tower in Siloam. The first was related to Christ by some who “were present at that season;” the second was related by Christ in his reply. One of these facts, the falling of the tower and its consequences, belonged to the realm of nature; the other, the slaughter of the Galileans, to the realm of civil or political life. But while they may be thus classified, they have also a moral and religious import and bearing. There is some fundamental element common to each of them which the great Teacher makes the groundwork of a common lesson and warning. Though they belong to different spheres and are totally different in character, in his view each teaches the indispensable necessity of repentance, and the certainty of destruction without repentance.

The connection between the events and the lesson deduced from them is somewhat obscure. He could not have meant that unless they repented they would all perish by the sword of Pilate, as did those Galileans; or be crushed to death by falling towers, as were those men in Siloam. In repentance there is no guarantee of security against the wrongs of tyranny, or against natural disasters; whereas it does save from that perishing or destruction of which Christ speaks. The lesson and warning therefore belong to a sphere different from that of either of the facts. To ascertain as accurately as we may be able the connecting link between them, and what it is that gives point and emphasis to the lesson is our present purpose.

In our interpretation of these and all similar events we are to exclude the idea that they are judicial or penal. Such was the popular notion. So thought Job’s friends: “Is not thy wickedness great, and thine iniquities infinite?” said Eliphaz, “Therefore snares are round about thee, and sudden fear troubleth thee, and abundance of waters cover thee.” So thought David’s enemies, when they derisively asked, “Where now is thy God?” Such too was the opinion of the disciples when they asked, “Who did sin, this man or his parents, that he was born blind?” Nor would we have to go very far or search very diligently even now to find persons holding this same view of the divine administration.

There is unquestionably a connection between natural and moral evil. They stand to each other in the relation of cause and effect. All the physical evils that afflict the human family are effects of sin, the fruits of transgression. On no other theory can we explain the disorders of the natural world, the multiform sufferings of sentient creatures, the misfortunes that blast our fairest hopes, the diseases that rack and destroy our bodies, the keener pains that tear our souls asunder and the heavier blows that break our hearts. A God of infinite wisdom, justice and love could not have been the author of that condition of things which we behold around us. Sin has brought all this wretchedness and ruin on our race. Had there been no transgression the glory of Eden would never have departed, and man, immortalized in the image of his Maker, would have been a stranger forever to sorrow and death. But while natural evil is the effect, it is not the punishment of sin. Innocent children often suffer keenest anguish. They have no guilt to be punished. Among those Galileans whom Pilate slew, or those on whom the tower fell, may have been some of God’s chosen ones; and the onset of the soldiery and the crash of the falling tower may have been but the signal for their triumphant enthronment amid the principalities of heaven. We know that one characteristic of the divine dispensations in every age has been their frequent apparent severity towards those most eminent for their faith and the holiness of their lives. His most obedient and loving children have oftenest wept under the burdens and tribulations of life. We do not attempt to explain it, but accept as a fact of his administration, which is of itself a sufficient refutation of the notion, that because a man suffers in this life he is to be adjudged a criminal, and that the greater his sufferings the greater must be his criminality.

In our interpretation we are to exclude also the idea of chance. Can there be under the government of God any such thing as an accident, a mere fortuity, an event coming to pass without efficient intelligent cause and without design? To this inquiry Christian philosophy responds with an emphatic negative. It teaches that God is to be seen in every work of nature and every event of providence — that there is nothing, however trivial it may appear to us, or however little it may affect the well-being of any creature of His hand, intelligent or unintelligent, that is for a moment unnoticed by Him or independent of Him.

There are some who willingly recognize His hand in those events the cause and purpose of which they can readily discover and the justice and wisdom of which they approve. They thus limit God’s operations by their capacity to comprehend them; whereas His ways are as far above our ways, and His thoughts above our thoughts as the heavens are above the earth. This deification of human intelligence is ludicrous; but this undeification of God is criminal.

There are others who err in the opposite direction. They deem it unnecessary to recognize God in those things which they can explain on natural principles. To understand an event is, with them, to put it out of the special dominion of God. But where there is mystery, or where the instrumental causes are so remote or so complicated that they cannot be detected, there God’s hand is to be acknowledged. The adoption of this principle would commit us to the proposition that “ignorance is the mother of devotion.” The less we know of God’s works, and word, and ways, the more reverent and devout we will be! In proportion to our advance in knowledge will be our advance towards atheism!

Of course all such notions are to be repudiated. God is to be seen in everything, everywhere, always; in the ordinary as well as the extraordinary events of human history; in those occurrences whose causes are patent to the most casual observer as well as in those whose springs lie in the inaccessible depths of the infinite; in the gentle zephyr and genial shower no less than in the crashing hurricane and the devastating flood; in sorrow and tears, in disease and death, as truly as in joyous, healthful life. The only view that elevates, cheers and gladdens men under the pressure of life’s difficulties, disappointments and sorrows, is that which represents God as absolute sovereign over all forces and agencies of the universe, and at the same time a compassionate Father who is good to all and whose tender mercies are over all His works.

But the government of God is in no sense dependent upon circumstances. It is not a government of caprice or whim, a sort of haphazard arrangement, veering hither and thither, now one thing and now another, according to the ever varying conditions of the universe. Government implies law. God governs or works according to law. Such are the adjustments and adaptations contrived by infinite wisdom that certain causes are followed in an invariable order by certain effects. This regular order of sequence of events, or of cause and effect, is what science calls law, which “science falsely so called” would exalt to absolute supremacy. We accept the term, but interpret it as expressive simply of God’s method of executing His own will or accomplishing His purposes.

This order of sequence, or law, is universal. It reigns in the worlds above us and in the earth beneath us. Every movement of the natural universe and every result of such movement is according to law. Without it science would be impossible; for science is but the discovery, formulation and study of causes and effects, or the laws reigning in the various departments of human research. We cannot forecast what future investigations may disclose; but we already know that no field of inquiry has been entered that did not at once reveal the presence and authority of law. It confronts us at every step that we take. It touches us at every point of our being-, and in every relation that we sustain. It grasps us with hooks of steel. We can no more get away from its control than we can get away from our own being.

It is uniform in its operation. It does not produce one effect today and a totally different effect tomorrow. The law of gravitation does not preserve order in the material universe at one period and create or allow confusion at another. Its results are the same now as on the morning of creation. So with all laws of the natural world of which we have any knowledge. The same is true of the world of mind, of thought, feeling and volition. Indeed nothing can be called law which has not this element of uniformity. Generalization must show that the order of sequence is invariable before the scientific man will write it down as a law.

It is irresistible in its movement and certain in its issue. It is silent and unobserved, perhaps unknown; but its movement is as majestic as the march of God; its aim is unerring. Put yourself in its way, cross its path, and it will grind you to powder. Its forces are all on your side, ministering to your happiness and security so long as you are in conformity with it; but ignore or oppose it, and it moves against you with the energy of omnipotence. Escape from its penalties is impossible.

But the universe is not an automaton. It did not create and does not govern itself. It is under law, it is true. But law cannot originate, execute, and perpetuate itself. It must have intelligence back of it, above it, in it. In itself considered it is unintelligent, inert, dead; it is nothing. It is vital, controlling, mighty, only by virtue of the divine intelligence and energy ever present in it and operating through it. Above all, and through all, and in all, is God, superintending, directing, and controlling every cause in the production of every effect, and in the evolution of the wondrous system of His providence.

If these views be correct, the slaying of those Galileans was not simply a capricious act of cruelty on the part of a bloodthirsty tyrant; but was an effect of an antecedent cause, or a combination of causes. That cause may have been in the well-known turbulent spirit of the Galileans; or in Pilate’s hostility to Herod, whose subjects they were; or in that general state of unrest and dissatisfaction which could be held in check only by the iron hand of military power. It may have been in the people, or it may have been in their ruler. At all events there was an efficient cause of which their perishing was the sequence. And wherever and whenever like conditions exist in government and in its subjects like tragedies will occur. The men on whom the tower in Siloam fell were slain by natural law, the law of gravitation. Moral character had nothing to do with their death. It was the natural and necessary effect of a natural cause. Anyone else, however saintly, would have perished under the same circumstances.

At this point we touch a connecting link between the historic facts of the text and the solemn lesson and warning deduced from them.

As a material being man is subject to the laws that govern the material world. The disregard or violation of those laws will issue with unerring certainty in the suffering of penalty. Neither penitence and prayer nor subsequent right living can avert it. The cause existing, the effect is sure. But man belongs also to the social and civil world. He sustains certain necessary relations to his fellow-man and to the government under which he lives. He is under the laws that govern these relations. He may be an ignorant or an unwilling subject; but that does not affect the question of their sovereignty over him. Willing or unwilling he cannot live in absolute isolation and independence. It follows that he is subject to the penalties affixed to the violation of the laws of these relations. And how surely, though some times slowly, the penalty follows the violation no student of human history, or of the times in which we live, can have failed to observe.

But he is also a moral and spiritual being. He belongs to a realm far above the merely material; above the sentient; above the social and political. He has never been able to completely shake off the conviction of his kinship to the invisible and eternal, and of his accountability to a supreme being. The savage knows that there is a God, and “seeks him, if haply he may feel after him and find him;” and though “in his blindness he bows down to wood and stone,” in doing so he gives proof of his inborn feeling of moral responsibility to a higher power. Men cannot educate themselves into the belief that their destiny in no higher than that of the brute creation. The glare of the most splendid culture cannot wholly blind them to the mighty future that awaits them. Nowhere and at no time has God “left himself without witness.” Whether men would or not, He makes them know something of the dignity of their nature and of their exalted relationship and destiny.

It were idle to suppose that law reigns less absolutely in this loftier sphere than in the lower; or that it is less uniform and irresistible in its operation and certain in its results. God is the same whether in time or in eternity. His will is the expression of Himself, whether that expression be in the laws of nature or in the laws of the moral and spiritual universe. He cannot be true to Himself in one department of His empire and untrue in another. “The good pleasure of His will ” is just as sure of accomplishment in the spiritual as in the natural world.

In dealing with us as spiritual beings, He manifests His matchless kindness. In the natural world we are left to our own intelligence and enterprise. We can ascertain its laws only by patient research. But the laws of the spiritual kingdom He has been pleased to reveal. “At sundry times and in divers manners He spake in time past unto the fathers by the prophets,” and “hath in these last days spoken unto us by His Son.” In this revelation He has defined for us our position, relations and duties. He publishes His law, authenticates it to our reason and conscience, and specifies its sanctions. This He has done so plainly that no one need be in doubt as to its import, or hope to plead ignorance in extenuation of criminality.

The great Teacher has summarized the law for us; “Then one of them, which was a lawyer, asked Him a question, tempting Him, and saying, Master, which is the great commandment in the law? Jesus said unto him, Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind. This is the first and great commandment. And the second is like unto it, Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself. On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets.”

But who of all our race, from Adam until now, has not violated this law; not once only, but often; not in one way only, but in ways without number? Instead of love supreme, the dominant feeling and force in the human heart is “enmity against God.” The life is but the expression of this enmity. Not simply forgetfulness of God and disregard of His claims, but positive alienation and active hostility is the attitude of the carnal mind towards Him. The result is that “judgment has come upon all men unto condemnation; “the sentence of death has “passed upon all men, for that all have sinned.” Will the sentence be executed? Unquestionably. Law without penalty is a nullity; and penalty unexecuted is a nullity. Failure in the execution of the penalty is the nullification of the law, and the nullification of the law is the dethronement of the lawgiver. If God be God and law be law, penalty, however dreadful, must of necessity follow violation. The Son of God, the brightness of His Father’s glory and the express image of His person, undertook to rescue the race from its peril. How did He do it? Not by annulling the law or abating one jot or tittle from its demands, but by putting Himself in the pathway of its resistless march and receiving and enduring in His own person all the bitterness and anguish of its curse. As it is written, “Christ hath redeemed us from the curse of the law, being made a curse for us.” Infinite tribute is thus paid to the inviolability and majesty of law, and absolute guarantee is given for its execution.

The death of Christ was “a full, perfect, and sufficient sacrifice, oblation, and satisfaction for the sins of the whole world.” But it did not abrogate a single statute of the divine code. Nor did it insure the salvation of any of our race except infants and idiots, and such adults as, from conditions which they did not create and could not control, are still in mental and moral infancy. But it did introduce a temporary reign of grace. But grace is not lawless. It is full, free, and infinitely efficacious; yet its administration is under conditions or laws as immutable as the divine nature. The fullness of the redemption that is in Christ Jesus avails nothing to him who disregards any of these conditions.

The first word of grace to sinful men is, Repent. The forerunner of Christ began his preaching with the words, “Repent ye; for the kingdom of heaven is at hand.” Jesus began His public ministry with the same words. Paul, preaching to the Athenians, said, “And the times of this ignorance God winked at; but now commandeth all men everywhere to repent.” Quotations might be multiplied almost indefinitely. The conclusion is that repentance is not simply a privilege of which a man may or may not avail himself according to his own pleasure, but an unalterable statute of the kingdom of grace. It is backed by competent authority — the same authority that on Sinai said, “Thou shalt have no other Gods before Me.” It is enforced by adequate sanction, a terrific penalty, “Except ye repent ye shall all likewise perish.” Its execution is as certain as infinite power can make it.

No elaborate definition of this law is necessary. The prophet expresses its demand clearly and fully when he says, “Let the wicked forsake his way, and the unrighteous man his thoughts; and let him return unto the Lord.” “Put away the evil of your doings from before Mine eyes.” It is more than a knowledge and confession of sin, a sorrow for it and a weeping over it; it may include these; but the absolutely essential element, that without which all other exercises of the soul are unavailing, is the immediate, unconditional, complete and final renunciation of sin. Anything less than this is not repentance, and therefore does not satisfy the claim of this law. The man who stops short of this has nothing to expect but the penalty of a dishonored statute.

This penalty is variously expressed. It is “indignation and wrath, tribulation and anguish;” it is “everlasting punishment;” “outer darkness;” “destruction from the presence of the Lord, from the glory of His power.” The meaning of these representations is gathered up and condensed in one word, perish. We know what it is for objects around us in nature to perish. We know what it is for men to perish by fire, or on the battlefield, or in the storm at sea. But what is it for a soul to perish? Or what is the death of the body when compared with that of the soul? What are the keenest pangs that can attend its dissolution when compared with the worm that dieth not and the fire that is not quenched? The bodily pain is soon past; the soul’s pain is eternal. It is death that never dies; a perishing that never reaches a climax. It is withering, blasting disappointment, bitter self-reproach, sullen, hopeless despair, pitiless remorse, all intensified by the knowledge of what might have been, and perpetual through all the ages. The wreck of a human soul! Who can conceive of the horror of its ruin! Happy the lot of the thief on the cross; happy the lot of the victims of inquisitorial tortures, or of the direst sufferings that human ingenuity and hate can inflict, when compared with the woes of a lost soul.

A soul is lost! A soul is lost!

While countless ages roll.

Mourn winds and floods! Mourn heaven and earth!

Of mortal and immortal birth,

All mourn a lost, lost soul!

Souls have perished by the million. They are perishing now. Gospel light is blazing around them; gospel invitations and promises are sounding in their ears; the Spirit is striving with them; and yet they are perishing. And God is too good not to permit them to perish. Every interest of His kingdom requires that the authority of law be maintained. But men will not submit; they will not repent; they will not yield to a requirement so simple, so reasonable, so honorable as the putting away of the evil of their doings. There is nothing left for them but to perish. There is nothing left for a God of love to do but to let the law take its course, or else introduce distrust, dismay, and anarchy into His kingdom. “Unto Thee, O Lord, belongeth mercy: for Thou renderest to every man according to his work.”

While the law may be a terror to the evildoer, it is the safeguard of the upright citizen. It is his friend, his protector, both when he wakes and when he sleeps. So the law of repentance, while dooming to hopeless destruction the impenitent, insures the safety of the penitent. “Except ye repent ye shall all likewise perish;” but if ye repent ye shall be saved; God will have mercy upon you and abundantly pardon all your iniquities, guide you by His counsel through life and afterwards receive you to glory.